Mickey Mantle’s Arizona Spring

This article was written by Mike Holden

This article was published in Mining Towns to Major Leagues (SABR 29, 1999)

1951 is remembered as the one and only year that the New York Yankees trained in Arizona. When the Yankees ventured west, the Cactus League was in its infancy. Only two teams were training in the Grand Canyon State—the Cleveland Indians and New York Giants had both moved to Arizona in 1947. The Yankees spent the spring of 1951 in Phoenix under a one-time-only swap with the Giants, who took over the Yankees’ St. Petersburg site in Florida. Del Webb, the Yankees co-owner and a Phoenix resident, had brokered the switch with Giants owner Horace Stoneham, because Webb reportedly wanted to show off the Bronx Bombers to his friends in Arizona.

1951 is remembered as the one and only year that the New York Yankees trained in Arizona. When the Yankees ventured west, the Cactus League was in its infancy. Only two teams were training in the Grand Canyon State—the Cleveland Indians and New York Giants had both moved to Arizona in 1947. The Yankees spent the spring of 1951 in Phoenix under a one-time-only swap with the Giants, who took over the Yankees’ St. Petersburg site in Florida. Del Webb, the Yankees co-owner and a Phoenix resident, had brokered the switch with Giants owner Horace Stoneham, because Webb reportedly wanted to show off the Bronx Bombers to his friends in Arizona.

The 1951 Yankees were a formidable club. The two-time defending world champions had swept the Philadelphia Phillies in the 1950 World Series. Manager Casey Stengel’s lineup included future Hall of Famers Joe DiMaggio, Yogi Berra and Phil Rizzuto. Although no one knew it at the time, Arizona fans watched the New Yorkers prepare for their third of five straight World Series victories.

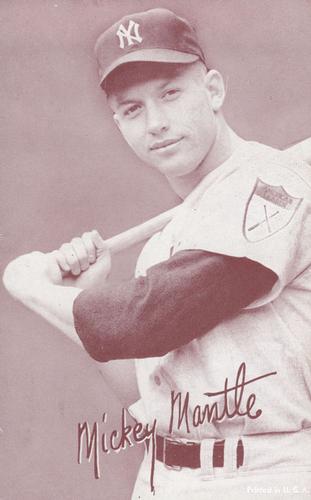

Two developments in the spring of 1951 made the Yankees’ lone visit to the Grand Canyon State even more memorable. First, Mickey Mantle, then a 19-year-old youngster with only one full season of pro experience, emerged on the baseball scene as the most “precocious juvenile player seen in a major camp since Mel Ott, at 16, came up to the Giants.” Second, the Yankee Clipper Joe DiMaggio announced shortly after arriving in Phoenix that “this is very likely my last year.”

Between the close of the 1950 season and the start of training camp the following spring, Mantle received more publicity than any other Yankee rookie. The switch-hitting Mantle had put up impressive offensive numbers in his first two years of professional baseball. After graduating from high school in 1949, he played 89 games at shortstop with Independence in the Class-D Kansas-Oklahoma-Missouri League and finished third in the batting race with a .313 mark. In 1950, his first full pro season, Mantle again played shortstop, this time for Class C Joplin in the Western Association and batted a league-leading .383 with 26 home runs and 136 RBIs.

Mantle was the talk of the hot stove league. On January 31, 1951, The Sporting News included a feature on Mantle entitled “Yanks to Take Early Look at Mantle. Rated Top Prospect in Minors at 19”. The article stated that “some big time scouts” have dubbed Mantle “as the No. 1 minor league prospect in the nation.” Tom Greenwade, the Yankees scout who signed Mantle, said in the same article, “Mick is the kind of player you dream about finding. You just hope you can run across one kid like him in a lifetime.” The article closed with more Mickey hype: “What more could a scout ask than a player just turned 19, as fast as a rabbit, with a rifle arm, tremendous power, proved under fire, with one third-place finish and one batting title in two years. … Like a find of uranium in your back yard.”

Despite such lavish praise, no one expected Mantle to jump from Class C to the defending champions when the Yankees came to Phoenix in 1951.

Before the start of major league spring training, Mantle was invited to attend a two-week instructional school for 28 of the organization’s top prospects. The “instructual school,” as Stengel called it, was a recent Yankee innovation where the young players received intensive instruction from Stengel, his coaches and several other instructors, including recently retired Yankee outfielder Tommy Henrich.

Mantle was scheduled to report on February 15 but he failed to show up. Yankee coach John Neun telegraphed Mantle in Commerce, Oklahoma on February 17 asking why he was not in Phoenix. Mantle responded that he had not received his travel allowance. “Action was prompt after that,” one New York paper reported, “and Mantle was on a plane to Phoenix the next day.”

Spring training in 1951 was not Mantle’s first visit to Phoenix. The Yankees had invited Mantle to another instructional school in February 1950 but the Phoenix camp was cancelled after only a few days when Commissioner Happy Chandler decided that the Yankees were violating the then March 1 official repo11ing date for training. Despite its short duration, Yankees general manager George Weiss called the first coaching school “an unqualified success.” One reason was that the Yankees had a chance to observe the 18-year-old Mantle, who made a big impression on the team’s brain trust. The Sporting News reported: “Mantle showed the Yankee officials enough to make them realize that here was a lad who was going to have his name written in many major league box scores.”

Yankees officials had debated about Mantle’s position for the upcoming 1951 campaign during the off-season. Mantle had struggled defensively at shortstop with over 100 errors in the 184 minor league games he had played in his first two seasons. General Manager Weiss said, “Some of our men say he should remain at short, some say he should be converted into an outfielder.”

Upon Mantle’s arrival in Phoenix on February 19, 1951, Stengel ended the debate by moving him from shortstop to the outfield. Stengel explained the decision: “To make a first-class shortstop out of Mantle would require a couple of years. anyway, but to convert the young man into an outfielder, well, that should not take too long.”

Stengel assigned Henrich to act as Mantle’s personal tutor. After only a couple of weeks of instruction, Henrich gave his student high marks. “I’ll tell you one thing,” he said. “The kid can catch the ball. He seems to have natural instincts of an outfielder. He can use his great speed there to more advantage than in the infield.” Henrich continued: “[H]e has the willingness to learn and work at the new job. I’ve been driving the hell out of him and he’s never complained once. At the end he’s always asking for more.”

Mantle was also enthusiastic over the switch from shortstop to outfield. “I don’t know why I’ve been wasting my time in the infield,” he said. “This fly-catching is right down my alley. It gives me a chance to use my speed. Of course, I’ve still got a bit to learn. Those long drives over your head are a lot harder to judge than the simple pops that a shortstop gets to handle. But that Henrich is a great teacher and I know I’ll learn the little tricks before too long. …”

Mantle and five other “school kids” were invited to stay in the major league camp when Stengel’s instructual school ended on February 28. Stengel wanted to take a better look at the “Jewel from Mine Country” (a nickname coined by the media in 1951 that did not stick).

With the Mantle story only beginning to unfold, DiMaggio made his stunning announcement on March 3: “This might be my last year. I would like to have a good year and then hang them up.” The news, which apparently flabbergasted Yankee management, increased the focus on Mantle, who the media quickly labeled as DiMaggio’s likely replacement in center field. “As the peerless DiMaggio prepares to bow out,” the New York Post observed, “perhaps his successor is at hand. It would be typical Yankee fortune.”

But before this prophecy could become a reality, Mantle needed to prove his worth. Mickey got off to a flying start. In the first intrasquad game on March 6, he connected for a triple and a home run off rookie pitcher Wally Hood. In the first regular exhibition game of the spring against the Cleveland Indians in Tucson on March 10, Mickey was in the starting lineup—in center field and batting third. He again was impressive with three hits in his first three at-bats. Two were singles off future Hall of Fame pitcher Early Wynn and the other was a ground-rule double into the roped off crowd in left field.

On March 12 in the Yankees’ Phoenix debut before an overflow crowd of 7,398 at old Municipal Stadium, Mantle started in center field but went hitless in one at bat. In the fourth inning, he showed his inexperience in the outfield when he lost Indian shortstop Ray Boone’s long fly in the sun and was struck on the forehead by the ball as he sought to get out of the way. Mantle’s sunglasses were broken and he left the game unhurt except for a “small egg” on his forehead.

Mickey, back in the starting lineup the following day, demonstrated his speed in the Yankees’ 10-8 ten-inning road victory over the Indians. He got three infield “leg” hits in five official trips and the New York Herald Tribune reported “in every case it was his ability to get down to first base ahead of the throw.”

Although the Yankees had a 34-game schedule that spring, only ten games were actually played in Arizona. After four games against the Indians in Phoenix and Tucson, the Yankees embarked on a 12-game trip through California with most of the contests against Pacific Coast League opponents.

Mantle continued to pummel enemy hurlers during the West Coast trip. He hit his first home run as a Yankee at Wrigley Field in Los Angeles—a 430-foot shot to deep center field. The homer was described “as one of the longest homers yet achieved in that park” and according to The Sporting News, “the ball traveled so fast that neither Center Fielder Bob Talbot nor the men in the press box ever saw it.” A couple of days later, Mickey belted his second roundtripper—another line drive shot—in an 11-0 victory over Joe Gordon’s Sacramento club. During the California swing, Mickey connected for five homers in 12 games and media attention continued to mount.

Stengel complained in San Francisco that “you writers have blowed up the kid so much that I gotta take him to New York with me.” But Mantle’s play on the field rather than media pressure would ultimately be the deciding factor. The Bronx Bombers returned to Phoenix on March 27 for six games at Municipal Stadium. The Yanks left the Valley of the Sun on April 2 for exhibition games in Texas and Kansas City before returning to New York.

It did not take long to figure out that Mantle was something special. Early in spring training, the New York writers labeled Mantle as “the new phenomenon” in the Yankees camp. The New York Times called Mantle “one of those ‘finds’ that comes along once in a generation.”

Stengel consistently praised Mantle in the press throughout spring training. On March 4, the Yankees skipper told the New York Post that Mantle is a natural hitter. “Most switch hitters are born of weakness,” Stengel said. “They can’t hit the opposite type of pitching, but this isn’t the case with Mantle.”

In mid-March, Stengel declared, “The kid can run and throw with any outfielder in the game right now. I think he might become the best switch hitter since Frankie Frisch. Tommy Henrich is working on his fielding and the improvement is already remarkable. … My, how that boy can run. He goes from first to third looking back at you, and the umpires always call him safe. That’s important. He’s the future, that boy. He’s the future.”

Mantle also impressed his Yankee teammates. DiMaggio declared in early April 1951 that “Mickey Mantle is the greatest prospect I can remember. Maybe he has to learn something about catching a fly ball, but that’s all. He can do everything else.” DiMaggio also expressed no resentment over the attention Mantle received during sp1ing training. “If he’s good enough to take my job,” Joe added, “I can always move to right or left.”

Stengel and the Yankees wrestled throughout the spring with the decision whether to promote Mantle to the majors. In discussing the Mantle situation, writer Dan Daniel said in The Sporting News that “to leap from Class C into ranks of the Yankees would be a feat without precedent on the club in the past 30 years.” But as early as March 5, one newspaper reported that Stengel had declared Mantle “has a good chance of making the big club.” By March 18, however, Stengel seemed to have changed his mind: “I’m going to send him out. I can’t keep a boy like that sitting on the bench. I’d rather have him play every day and learning to catch flyballs in the sunlight. He’s never played before except under the lights. But I’ll have him where I can get hold of him in a hurry any time during the season.” The Yankees skipper realized that a four-classification jump was a big risk but he said in early April, “If he has what it takes I’ll take the gamble.”

As the Yankees prepared to depart Phoenix on April 2, New York Times writer James P. Dawson summed up Mantle’s spring training performance: “[T]he name that stood out when the Yanks started training here more than a month ago stands out even more as the champions prepare to break camp for the homeward trip to what the camp hopes will be the third straight pennant for Manager Casey Stengel. The name is Mickey Mantle. It is worn by a husky, 19-year-old … and unless all signs fail, this nan1e eventually will go right down through the annals of baseball like some of the other greats.”

Mickey’s first big league spring was not trouble-free. The Korean war was ongoing in 1951 and the military draft was in effect. The Yankees’ roster had already been depleted with Whitey Ford, Billy Martin, Dave Madison and Artie Schult in the service. Mickey was classified as 4-F—unsuitable for military service—because of acute osteomyelitis in his left ankle. He had suffered an injury during a high-school football game and an infected hematoma led to osteomyelitis. The condition was acute enough to cause changes to the bone structure in the vicinity of his ankle. However, apparently because of public pressure, Mantle was summoned by his Miami, Oklahoma draft board to report for a reexamination late in spring training. With considerable media attention, the doctors reviewed Mantle’s case and came to the same conclusion—he was still unsuitable for military service. After the reexamination on April 11, Mickey flew to New York to join the Yankees for their final spring training contests against the Brooklyn Dodgers.

Mickey had an exceptional spring in 1951. He batted .402 and led the club with nine home runs and 31 RBIs. In the nine spring games Mantle played in Phoenix and Tucson, he hit a remarkable .469 (15-for-32) with three doubles, six RBIs and nine runs scored. Interestingly, none of Mantle’s nine spring roundtrippers was launched in Arizona.

Mantle later recalled in his autobiography, Whitey and Mickey, that the Yankees’ one-time spring switch to Arizona may have hastened his rise to the majors. “If we had been in St. Petersburg, I wouldn’t have hit all of those home runs like I was hitting in Phoenix. I must have hit about fifteen home runs [actually nine], but the ball carries a lot better there because the air is dry and light, and you can seen the ball good because the air is so clear. They just carry better there, and I don’t think I would have caught the press’s attention—or Casey’s—in St. Pete’s like I did in Phoenix.”

Mantle made the Yankees’ roster in 1951 at age 19 and was the starting right fielder in the team’s season opener against the Boston Red Sox in Yankee Stadium. In less than two years, he had jumped from a high school team into the ranks of the defending world champions. When The Sporting News interviewed Mantle in the clubhouse before the opening game, he expressed disbelief about his meteoric rise to the majors: “I somehow get the feeling that I hadn’t ought to be here. That maybe it’s a mistake, after all, and I am supposed to be in Kansas City. Now … please do not misunderstand this statement, I do not lack confidence. If I did I would not be sitting here … a Yankee. It is just that I am awed by the history of the New York club and by my company.”

Almost fifty years have passed since the Bronx Bombers trained in the Grand Canyon State but that visit remains as one of the most memorable chapters in Arizona baseball history. One reason is that Mickey Mantle made the most of his only Arizona spring.

Mike Holden is a Phoenix lawyer and publisher of Baseball AZ, a monthly newsletter focusing on baseball in Arizona.