Minor League Baseball and Affiliations in Québec: The Solutions or the Causes of All Problems?

This article was written by Christian Trudeau

This article was published in When Minor League Baseball Almost Went Bust: 1946-1963

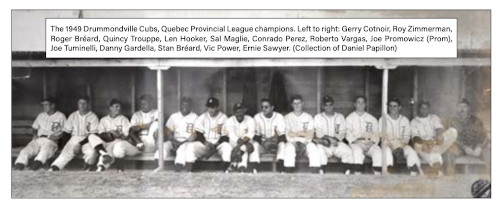

The 1949 Drummondville Cubs, Quebec Provincial League champions. Left to right: Gerry Cotnoir, Roy Zimmerman, Roger Bréard, Quincy Trouppe, Len Hooker, Sal Maglie, Conrado Perez, Roberto Vargas, Joe Promowicz (Prom), Joe luminelli, Danny Gardella, Stan Bréard, Vic Power, Ernie Sawyer. (Collection of Daniel Papillon)

On the afternoon of May 8, 1949, 4,000 fans crammed the stands in Drummondville, Québec, on Opening Day in the Provincial League, for a game against Sherbrooke. After the game, the Sherbrooke Athlétiques and the Drummondville Cubs drove to Sherbrooke for a rematch that night, playing in front of 4,200 spectators, with many undoubtedly having traveled the 50 miles to attend both games. If you could have told fans on that day about the future of the game, few would have believed that a mere six years later, professional baseball would be in its dying days locally, with most teams struggling to attract 500 spectators to a game.1

However, 1949 fans might have agreed that the situation could not last forever. The Provincial League operated outside of the umbrella of the National Association of Professional Baseball Leagues, which included all minor leagues recognized by the major leagues and which regulated transfers of players and salaries, among other things. Without NAPBL constraints, the salaries paid to many players in the Provincial League were too high for the league’s level of play. On the field that day were Sal Maglie, Max Lanier, Adrián Zabala, Danny Gardella, Roy Zimmerman, Fred Martin, and Harry Feldman, all unable to find work elsewhere after being suspended by Commissioner Happy Chandler for signing with the Mexican League in 1945.2 Also present were Silvio Garcia, Claro Duany, and Quincy Trouppe, who lacked opportunities from the major leagues, which was still early in its integration process. Finally, teams also had strong local players in Roland Gladu, Stan Bréard, and NHL player Normand Dussault.3

It was reported years later that the weekly payroll of the Drummondville Cubs was around $2,500, a tremendous amount for a team in a city of 14,000.4 League President Albert Molini, in an interview printed in La Tribune de Sherbrooke, explained how this was possible: “With such players, fans have the impression of seeing major league games. We can pay them high salaries with a system in which rich fans, merchants and firms guarantee salaries.” The article went on to say, “Molini believes Drummondville is paying Max Lanier $12,000 in addition to certain bonuses, bringing his salary to $20,000. These bonuses include lodging, food, clothing and cash prizes from fans.”5

The bubble partially burst in June when the Mexican League jumpers were reinstated. The league lost many of its stars like Lanier and Zabala, but was able to convince some, like Maglie, to stay. That 1949 season was successful on some level. League notoriety skyrocketed, the crowds were good, averaging between 1,500 and 2,000. The finances, however, were more problematic, and quickly Molini’s efforts turned to joining the National Association, to rein in the out-of-control spending.

The move garnered almost unanimous approval. Paul Parizeau, of Le Canada Newspaper summarized the general opinion: “With the rivalries being settled with fistfuls of dollars, Provincial League teams were heading toward bankruptcy, and it is a guarantee that the league would not have survived long. … Did players like Max Lanier, for example, provide performances that warranted the salaries they were paid? Probably not. These players sat on their reputations, more anxious to get their paychecks than to perform to their full potential. … They simply waited for their recall by the major clubs and picked up whatever they could while waiting.”6

The Provincial League joined the NAPBL for 1950, with all six teams from 1949 making the jump. Molini had argued for a Class-B designation, given the caliber it enjoyed and the large attendance it attracted,but to no avail. Given the population of its cities, it received a Class-C designation. Molini did, however, extract a few concessions. The usual Class-C salary cap of $3,400 monthly was increased by 5 percent, presumably for the added difficulties of operating in Canada. American players were to be paid in equal parts Canadian and American dollars. Teams were required to dress at least four rookies and no more than eight veterans for each game.7

Teams had to attract players to Québec, as they still operated independently, with no major-league affiliation. While more challenging given the lower salaries, newspaper columnists openly advocated for a system of bonuses to attract players, with the added benefit of keeping them “properly motivated.”8 The bonuses, however, nullified the biggest benefit of the NAPBL, its unofficial salary cap.

On the field, the transition was successful, so much so that Québec City and Trois-Rivières left the Class-C Canadian-American League for the Provincial League, in time for the 1951 season. The caliber remained high, in part because former Negro League players were targeted. For instance, the 1951 Sherbrooke Athlétiques won the pennant and the playoffs with a lineup that included Ray Brown, Claro Duany, Silvio Garcia, and Terris McDuffie.

The Québec Braves came to the Provincial League in 1951 having a strong relationship with the Boston Braves. While not officially affiliated, the Québec Braves had enjoyed a partnership with the National League team in previous years. It had been quite fruitful, in fact, with the 1950 edition selected, in 2001, as one of the top 100 minor-league teams of all time, in celebration of the centennial of the National Association of Professional Baseball Leagues.9 Moving to a formal affiliation in 1951, the Québec Braves were less dominant in their first Provincial League season, but had a stable roster, strong finances, and finished a solid fourth in the eight-team league.

There were only six teams for the 1952 season, but they all had affiliations in place.10 League President Molini enlisted the help of George McDonald, former umpire supervisor for the minor leagues, to secure these partnerships as major-league teams were reducing the number of such affiliations. The affiliations were seen as a way to finally curtail the arms race. “In 1952, Provincial League teams will not need to spend fabulous amounts of money to sign players. They will be able to obtain players for reasonable salaries. Therefore, they will improve their financial situation while still providing excellent baseball to its fans. If next summer attendances for games in the Molini circuit are as large as last summer, teams can hope to turn a profit for the season.”11

The news was well received across the league. For instance, the Montreal newspaper Le Front Ouvrier commented: “The caliber of the game will not be as strong this year, but spectators will no longer see these old-timers who have come to our city to pocket large salaries and then mock us. A fighting spirit will replace these overrated reputations, because these young players … will only have one desire: to climb higher every day to reach the major leagues if possible.”12

The league was even featured in a long article in the Montreal Star, after being mostly ignored by the English-language Montreal press. It mostly reflected on the evolution since the outlaw days but concluded that “[h]ockey may be our national game, but in these cities, they love baseball. Of the members, only Québec City operates a hockey team on a major scale. Yet they spend $100,000 to run a ballclub. It’s a good league, Albert Molini says it’s the best!”13

One group, however, was less happy with the changes: the veteran players, particularly the local ones, who were driven out of the league. Most found a new home close by, in two local leagues that filled the gap. The Laurentian League (mostly based north of Montreal) and the Québec Senior League (south of Québec City) had operated as loosely organized semipro leagues since the end of World War II but had grown as Provincial League teams shed veterans not of interest to their major-league bosses. In 1952 the level of these leagues was quite uneven, with some teams still operating almost exclusively with local players, but others had rosters that could compete in the Provincial League. In the Laurentian League, Lachute fielded many former Negro League players (Len Pearson, Jimmie Armstead, Pat Scantlebury, Walter Hardy, Len Hooker), while St. Jérôme opened its wallet so that Bob Wiesler, a well-regarded New York Yankees prospect, could fly in every weekend from his base in Syracuse, where he was serving in the Army. In the Québec Senior League, Roland Gladu brought former Sherbrooke teammates Ray Brown and Armando Roche to Thetford Mines, together with former opponent Ernest Burke. The main opposition came from Plessisville, led by local veterans Stan and Roger Bréard, Paul Martin, and NHL players Normand Dussault and Gilles Dubé, and helped by several veterans of the Provincial League.

Teams in smaller cities in both the Laurentian and Senior Leagues struggled to follow the leaders, and two teams disbanded before the end of the season. This gave the public a rare glimpse into the finances of one of the disbanded teams, Ste. Thérèse of the Laurentian League. For 2 Y months of activities, expenses were $15,442, including $6,887 in salaries. Revenues were $9,963, for a deficit of $5,478.14

When local star Jean-Pierre Roy jumped his contract with Ottawa of the International league to join St. Eustache of the Laurentian League,15 there was a threat that the league would be considered as outlaw, and its players ineligible for National Association play. Provincial League President Albert Molini offered his advice, cautioning that the path taken by the Provincial League, which had forced the hands of minor-league officials by becoming an inescapable outlaw league, was highly unusual, and that offering higher salaries than the minor leagues was a suicide. According to him, cities should have a team with a caliber corresponding to its means.16

The Provincial League fielded eight teams for 1953, as Sherbrooke returned with a new ballpark, its previous one having burned after the 1951 season. To accompany them, Thetford Mines was plucked from the Québec Senior League, killing the loop in the process. The prestige of joining the minor leagues made the move a no-brainer for Thetford Mines, once the financial issues were sufficiently resolved. As part of that discussion, it was learned that it cost about $50,000 to operate a team. With 63 home games, but many doubleheaders and possible rainouts, it required about $1,000 in revenues, or 1,200 paying customers, per home date.17

A few years before, attracting 1,200 fans per game was almost a given. In 1950 the league average was over 1,600 per game, and that was before accepting the bigger cities Trois-Rivières and Québec City, both with ballparks that could host up to 5,000 fans. But by 1953 that was a challenge, and only Trois-Rivières, Québec City, and Thetford Mines, where Provincial League baseball was a novelty, achieved it. Sherbrooke, a Cleveland Indians farm team, attracted only 58,288 fans, less than 1,000 per game, even with a pennant-winning team playing in a new ballpark. In their previous season in 1951, they had attracted 100,933 fans, about 1,750 per game. Saint-Hyacinthe, which attracted only 30,051 fans, gave up after the season. Granby, which had only 46,935 fans with a second-place team, also withdrew from the league, and the Provincial League shrank back to six teams for 1954. Attendance was also down for the International League’s Montreal Royals. The factors that led to the slow but steady decline were like elsewhere in North America: more entertainment options, more families visiting their cottages, and of course television, although it arrived relatively late to Canada.19 The Canadian Broadcasting Corporation started broadcasting in English and French in 1952. Some of the first broadcasts in French were Montreal Royals games,20 although it was seen more as a factor in the attendance decline in the Provincial and Laurentian Leagues than for the Royals.21 The Laurentian League president proposed another explanation: Canadian fans might differ from American ones, requiring a winning team to be interested.22

One potential factor mentioned in the decline, particularly in Sherbrooke where the Cleveland Indians directly managed their affiliate in 1953-54, was the lack of consideration given to local particularities. The general manager appointed by the Indians was said to have arrived from California with the mindset of having to show real baseball to an ignorant population. Operating the team in English only was also a major faux pas in a province where the majority of the population speaks French.23 While foreign talent had been the main drivers of the Provincial League for many years, the teams were under control of local interests; with affiliation these local actors had little or nothing to say anymore, which inevitably led to such conflicts.

In the Provincial League, these forces were combined with the decline in the quality of play. While an imperfect measure, Table 2 lists the number of future and former American League and National League players, as well as the number of former Negro League players. The changes in the composition of the league are staggering. Farnham, which fielded an almost all-Black team, dropped out of the league after 1951, partly explaining the drastic decline in former Negro League players from 1951 to 1952, and demonstrated the aforementioned changes in focus. The few former Negro League players who remained after 1951 were mostly younger players considered to be prospects. Veterans were mostly gone. Many went to the Manitoba-Dakota League, but a decent number stayed in the Québec Senior League and the Laurentian League.

Already in 1949, there were warnings about the caliber of play: “Fans are seeing too high caliber baseball right now to accept Class C or Class D levels.”25 By 1953, fans were tired of the constant subscription drives to try to keep their teams afloat. While it might have made sense to give a few dollars to the local baseball team to acquire the former major leaguer who might help beat the rival town, it was a less interesting proposition to help the finances of a team with a roster partly controlled by the Philadelphia Phillies or Washington Senators.

The Provincial League’s early advantage to break in young Black and Latino players quickly vanished. The difficult Canadian climate also proved to be a challenge, as the needs of the National Association stretched the schedule as much as the warm weather would permit, fitting 130 games into just over four months, from May to early September. Before 1950, the league was playing a 100-game schedule. And more than the quality of the players, it was the turnover that hurt the most, especially since many of the stars who were coming back every year were local players like Roland Gladu and Stan Bréard, now chased to the Laurentian League.26

If the level of play was a factor in the decline of the Provincial League, it was not the only one, as the Laurentian League, playing a style of baseball closer to the 1948-51 Provincial League, was also struggling mightily. To keep salaries under control, an affiliation with the NAPBL and major-league teams was considered. After the 1953 season, the league president, Dr. Alfred Cherrier, had a mandate from the team owners to apply for admission into the National Association. The plan was to join as a Class-C league, the same level as the Provincial League. While the two leagues would operate separately, Cherrier would encourage a playoff series between the two champions. While financial pressures were the main reasons for proposing affiliation, one factor mentioned was the ability to enforce contracts.27 According to rumors, during the 1953 playoffs seven players threatened to quit unless given an extra $100 per week.28 Similar stories had convinced the Provincial League to join the NAPBL in both 1939 and 1949.29

The plan received the support of George Trautman, president of the NAPBL, and admission was expected heading into their annual meeting in December 1953.30 It never happened. It seems likely that the National Association, using its population guidelines, wanted to assign the Laurentian League to a Class-D level. For some of the owners, it was Class C or nothing, for fear of being seen as simply a feeder for the Provincial League.31

The Laurentian League continued outside of the NAPBL for 1954, but it was a struggle. Attendance numbers are tougher to find for the league, but we have a few examples.32 In St. Jérôme, a town of 25,000, attendance fell from 44,000 in 1952 to 10,000 in 1954, in about 35 home games.33 The situation was so dire that a fan climbed in a light tower and vowed to stay there until the team could attract a crowd of 1,000 spectators. He stayed there for seven days before being rescued by a crowd of 1,067 fans.34 In Joliette, population 10,000, attendance fell from 36,000 to 20,000 over the same period, with deficits of about $10,000 per year. Owners claimed that 40,000 in attendance would have been enough to break even.35

The 1954 playoff finals featured two of the smaller markets, Lachute and Ste. Therese. One of the games drew only 300 spectators.36 The next spring, owners pulled the plug, given the bulging deficits and lack of attendance.37

Meanwhile, the Provincial League was also in trouble. Drummondville, which five years earlier was the toast of the game, had suffered through three difficult years, drawing fewer than 650 fans per game. The team was replaced for 1955 by Burlington, Vermont, the first venture outside La Belle Province. It drew relatively well, 51,267 fans for the season. Sadly, while that would have been dead last in 1950, it was now the second highest draw, a distant second to Québec City, which drew 101,695 while winning its fourth consecutive playoff championship. Adding Burlington meant additional travel expenses, so on balance the addition was probably a net loss for the league.

As the season was fading, Albert Molini resigned as president of the league, a job he had held since 1948. Under his guidance the league rose from semipro to top outlaw league to the NAPBL to a full-fledged part of farm systems. Weakened by health issues, Molini had been less active in the last few years, perhaps exacerbating the issues the league was facing.38 The league did not survive his departure.

Sherbrooke, dropped by the Cleveland Indians, quickly announced that it would not come back. Québec City, Thetford Mines, and Burlington were willing to continue, but Trois-Rivieres and St. Jean were hesitant. George McDonald, who had occupied various roles in the Philadelphia/Kansas City Athletics organization, including as general manager in St. Hyacinthe, Burlington, and Ottawa (International League), and had helped Molini in 1952 secure affiliations, was named president.39 He lobbied the National Association to allow a four-or five-team league for 1956, and President Trautman responded positively, claiming that while the Association was not interested in four-team leagues, “it would however make an exception for the Provincial League, because of its importance among Class C circuits. The Provincial League is an old league that deserves to survive.” But when both Trois-Rivières and St. Jean failed to meet a mid-April deadline, it became evident that a three-league team was impossible, and the National Association pulled the plug.40

As a sign that the fortunes of minor-league baseball had rapidly changed, Trautman was now the one courting the Provincial League for a revival. In July 1956 he met with representatives of the league in Montreal.41 When these representatives insisted on getting a Class-B league, the project did not go anywhere.42 Trautman would try again in 1958, this time with Montrealer Frank Shaughnessy, president of the International League. The Provincial League would become a Rookie League, operating from early June to late August, limiting the weather problems.43 Once again, the project did not materialize.

Meanwhile, baseball returned to its local roots. The new Provincial League contacted Trautman to return to the NAPBL in I960.44 It did not, but as American players were accepted in greater numbers, the level of play increased quickly. By the end of the 1960s, it was among the top leagues outside of the NAPBL, attracting players recently released by major-league organizations, as well as young Latino players.45 As was the case two decades earlier, deficits soared, and the Rookie League project was considered once again.46 Eventually, as the gap between Québec, Trois-Rivières, and the smaller cities increased, the two larger cities moved to the Double-A Eastern League for 1971. Sherbrooke followed in 1972, eventually replaced by Thetford Mines in 1974. By the end of the 1977 season, however, the Eastern League had left the province. While Québec and Trois-Rivières eventually returned to independent minor leagues, affiliated baseball has yet to return to the province.

CHRISTIAN TRUDEAU is a professor of economics at the University of Windsor (Ontario). He is a game theory specialist by day, and a historian of Québec baseball by night. He is a co-editor of the Journal of Canadian Baseball /Revue du baseball canadien.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This article was edited by Marshall Adesman and fact-checked by Mike Huber.

NOTES

1 Attendance figures are given in Table I, below.

2 For more details on the so-called Mexican League jumpers and their link to Québec, see Bill Young, “From Mexico to Québec: Baseball’s Forgotten Giants,” The National Pastime: Baseball in the Big Apple (Phoenix: SABR, 2017).

3 Maglie, Lanier, Gardella, Zimmerman, Trouppe, and Bréard suited up for Drummondville, and Zabala, Martin, Feldman, Garcia, Duany, Gladu, and Dussault for Sherbrooke.

4 The report totals $2,145 f°r M players but does not include Max Lanier. Sal Maglie is the highest paid, at $350 weekly. “Les potins du jeudi,” La Voix de TEst, February 19,1976: 1-10. Throughout the article money figures are in Canadian dollars, roughly on par with the US dollar in the period considered. Population data is from the 1951 Canadian census, cited in “Les régions métropolitaines de recensement, Cahier 1,” Bureau de la Statistique du Québec, 1998: 34-37.

5 Most of the quotes in this article are translated from French. “Lanier a plus à Drummondville que ne lui offrent les Cardinals,” La Tribune de Sherbrooke, June 8,1949: 16.

6 Paul Parizeau, “Du Soir au lendemain,” Le Canada, January 19 1950: 8.

7 Claude Savary, “Vues et Revues sur les Sports,” Le Courrier de St-Hyacinthe, March 24 1950: 12.

8 Parizeau.

9 See https://www.baseball-reference.com/bullpen/ioo_Best_Minor_League_Baseball_Teams, accessed September 5, 2022.

10 Sherbrooke took a year off as its ballpark burned to the ground in the night following the 1951 championship. Famham, the smallest town in the circuit, dropped out of the league. In addition to Québec (Boston Braves), the other affiliations were St. Hyacinthe (Philadelphia A’s), St. Jean (Pittsburgh), Drummondville (Washington), and Granby (Philadelphia Phillies). Trois-Rivières had a partnership with the New York Yankees that was short of a formal affiliation.

11 Bert Soulière, “Horizons Sportifs,” Le Canada, January 9, 1952: 9.

12 Michel Beauregard, “Equipes jeunes, rapides, combattives,” Le Front Ouvrier, May 10, 1952: 11.

13 Lloyd McGowan, “Minus Sal Maglie, Lanier, Molini Loop Boom,” Montreal Star, May 31,1952: 31.

14 Georges Bonin, “La Parade des Sports,” L’Eclaireur, August 21, 1952: 8.

15 Roy claimed it was to be closer to his ill mother.

16 Paul Guertin, “La suspension de Jean-Pierre Roy aurait de sérieuses répercussions,” Le Front Ouvrier, July 26,1952: 10.

17 “Thetford Mines figurera-t-il dans la Provinciale l’an prochain,” Le Canadien, October 2, 1952: 4.

18 Years Québec City and Trois-Rivières spent in the Canadian American League are in italics. Sources for seasons in the NABPL are the annual Sporting News Official Baseball Guides. The numbers for the 1947-49 Provincial Leagues are less reliable. Sources are “Ligue de baseball provinciale 1947,” Le Clairon de St-Hyacinthe, October 10, 1947: 10, “Ligue de baseball provinciale 1948—Statistiques officielles,” Le Clairon de St-Hyacinthe, October 8, 1948: io, Roger Cyr, “Ça et là dans les sports,” Le Clairon de St-Hyacinf/ie, October 7,1949: 10.

19 “Une baisse des assistances à Montréal,” Le Front Ouvrier, August 8, 1953: 13. One distinction with the decline of minor-league baseball in the United States is the proliferation of air-conditioning, not as much a factor in Canada given the climate.

20 “Les premiers pas de la télévision de Radio-Canada,” Radio-Canada, https://ici.radio-canada.ca/nouvelle/1046151/television-baseball-hockey-histoire-archives, accessed on August 17, 2022.

21 “Une baisse des assistances à Montréal,” Le Front Ouvrier, August 8, 1953: 13-

22 “La ligue des Laurentides souhaite entrer dans le baseball organisé,” Le Front Ouvrier, September 5, 1953: 13.

23 “Tribune Libre,” La Tribune, September 24, 1953: 16.

24 Compiled from https://www.lesfantomesdustade.ca/mlb and with help from Gary Fink and his database of Black players in the first decade of integration.

25 Noël Sylvain, “Deux nouveaux lanceurs pour les Cubs de Drummondville,” Le Front Ouvrier, July 23, 1949: 14.

26 Jean Chartier, “Randonnée Sportive,” La Tribune, September 23,1955: 10.

27 “La ligue des Laurentides souhaite entrer dans le baseball organisé.”

28 Oscar Major, “Dans le monde sportif,” Le Samedi, January 30,1954: 11.

29 Christian Trudeau, “The 1938-40 Québec Provincial League: The Rise and Fall of an Outlaw League,” Baseball Research Journal 50, No. 2 (Phoenix: SABR, 2021), 95-104.

30 “Sur le front du baseball: Une petit série mondiale?,” Le Clairon de St-Hyacinthe, October 16,1953: 9.

31 Robert Desjardins, “En pleine lumière: La ligue des Laurentides n’est pas ‘mûre’ pour le baseball organisé,” Le Petit Journal, December 20, 1953: 89.

32 Population numbers in this paragraph are from 1961. See “Les régions métropolitaines de recensement, Cahier 1,” Bureau de la Statistique du Québec, 1998: 34-37.

33 “St-Jérôme n’aime plus le baseball,” Le Petit Journal, October 24, 1954: 98.

34 “Jean Barrette met le pied à terre,” L’Avenir du Nord, August 5, 1954: 9.

35 “Pas de baseball senior au stade de Joliette,” L’Action Catholique, May 10, 1955:’6.

36 Gaston Laporte, “Les Sports en revue,” L’Avenir du Nord, September 16,1954: 7-

37 “Pas de baseball cet été dans la Ligue des Laurentides,” L’étoile du Nord, April 13, 1955: 7.

38 Jean Chartier, “Le président Albert Molini donne sa démission,” La Tribune de Sherbrooke, September 23, 1955: 10.

39 “George McDonald succède définitivement à Albert Molini,” La Patrie, November 26,1955: 68.

40 “Où en est le baseball? Trois clubs en mauvaise posture,” Le Nouvelliste, April 17, 1956: 1.

41 “George Trautman désire faire revivre la Ligue Provinciale,” Montréal-Matin, July 21, 1956: 21.

42 Albert Vidal, “Nouvelles et commentaires,” Le Courrier de St-Hyacinthe, October 5, 1956: 12.

43 “Shaughnessy et Trautman réssuciteraient la ligue Provinciale—Assemblée à Montréal, le 3,” La Tribune de Sherbrooke, August 27,1958: 10.

44 “De Trautman, Paulin reçoit une réponse,” La Presse, June 30, i960: 12.

45 George Gmelch, Playing with Tigers: A Minor League Chronicle of the Sixties (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2016), 204.

46 André Gagnon, “Sports Atout,” La Tribune de Sherbrooke, September 12, 1969: 2-2.