Mordecai Peter Centennial Brown

This article was written by Paul C. Frisz

This article was published in 1976 Baseball Research Journal

He had one name form the Old Testament, one from the New, and one which commemorated the fact that he was born in the centennial year of 1876. But he became better known as “Three-Finger” Brown because of an accident he sustained in childhood.

Considering that the Society for American Baseball Research selected him as the outstanding baseball personality born in 1876, a brief review of his career would be in order. First off, some clarification about his accident is necessary. Although young “Mine” Brown did spend several years in the coal mines of his native Indiana, he did not lose his finger in a mining accident.

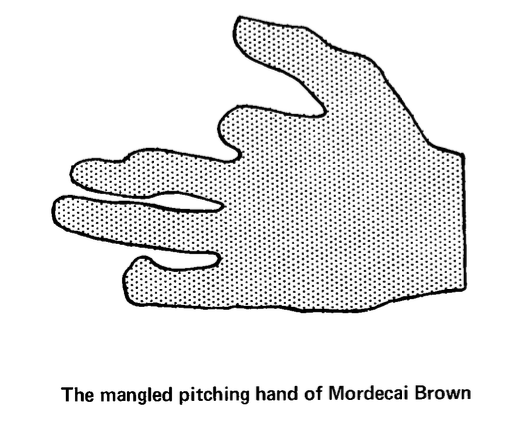

The accident took place on his uncle’s farm when Brownie was only 7 years old. He caught his right hand in a corn grinder and had it badly chewed up. When he was taken to the doctor, it was found necessary to amputate almost all of the forefinger. His second finger was saved but it was mangled, as shown in the accompanying drawing. The sketch also shows his little finger as being in bad shape. This was not caused by the feed grinder accident, but resulted from trying to stop a shot through the middle when he was pitching.

Brown was a good semipro player but didn’t consider baseball as a serious career until he was 24. He started as an infielder with Terre Haute in 1901, but soon switched to the mound. He found that he could get a good spin on the ball by releasing it off the stub of his forefinger.

The former coal miner went from Omaha in 1902 to the St. Louis Cardinals in 1903. He was 26 when he broke into the majors. After one year with the tail-end Cardinals, Brown was traded with catcher Jack O’Neill to the Cubs for pitcher Jack Taylor. The Cubs had not had a first rate club in years, but new manager Frank Chance was building them into a contender. Brown blossomed forth in 1906 with a 26-6 record as Chicago racked up 116 victories, an all-time major league record. Nevertheless, the White Sox beat them in the World Series.

In 1907, Brown won 20 games and the Cubs won the pennant and swept the Tigers in the World Series. The next year he upped his victories to 29 and the Cubs again won the Series from Detroit.

These were glory years for the Cubs, even though the Giants beat them out of the pennant in 1909. Brown nevertheless won 27 games. In 1901 he won 25 and Chicago took its 4th pennant in 5 years.

Brown again won more than 20 games in 1911, but the next year he missed much of the season because of injuries. He hurled for Cincinnati in 1913, and spent two moderately successful years in the Federal

League 1914-15, part of which time he served as manager. He returned to the Cubs in 1916, where he closed out his career on September 4 in a specially arranged final duel with Christy Mathewson. Matty, who had become manager of Cincinnati, beat Brown 10-8 in the final major league contest for each.

It was the 25th time the two had faced each other on the mound. They both had won 12 games, but Brown had the edge because Matty had lost 13 to his 10. Three games were credited to other Cub hurlers. One game the three-fingered ace lost was the 1-0 no-hitter that Matty pitched on June 13, 1905. After that, Brown beat him 9 straight times between 1905 and the end of the 1908 season. The final win in that streak was the famous playoff of the Cub-Giant game where Merkle failed to touch second base. As the two teams finished in a tie at the end of the season, the game was scheduled for October 8, and Jack Pfiester, the “Giant Killer,” started for the Cubs. But Brown relieved him in the first inning when he got into trouble and won the pressure game over Matty 4-2.

Pitching under pressure was one of his strong points. He was frequently called to work in relief and when he wasn’t carting off the victory, he was saving games for others. He is credited with 48 saves, a much higher total than any other hurler of his era. He could come in without warming up and show excellent control in spite of his mangled pitching hand. Brown, with his forefinger missing, would toss his curve ball with a straight overhand motion. The ball would drop down and away from righthanded batters, who would frequently hit it into the dirt. As a former infielder, he fielded his position well and was death on bunts.

As a reporter wrote in 1917,

“Brown made his very injuries work for him. He claimed, and we believe with reason, that the loss of his first finger enabled him to get a sharper break on his curve ball than would have been possible with a complete set of fingers. Anyway, he had a beautiful curve, a fine fast ball, and amazing control. All these with a hand that looks like a veteran of the seven years war.”

It was an unusual handicap for a pitcher and undoubtedly contributed to baseball lore of the period. After Brown became famous as a pitcher, and even long after he retired and operated a garage in Terre Haute, people still went out to his uncle’s farm to view the feed grinder, since stored and polished, which “launched” the career of “Three-Finger” Brown.