Movies, Bullfights, and Baseball, Too: Astrodome Built for Spectacle First and Sports Second

This article was written by Eric Robinson

This article was published in The National Pastime: Baseball in the Space Age (Houston, 2014)

Instead of using shovels, Judge Roy Hofheinz and other officials fire six-shooters at the ceremonial ground-breaking. (PHOTOS COURTESY OF THE HOUSTON ASTROS)

“Houston Astrodome or Bust”

—Tagline for Bad News Bears in Breaking Training

The Astrodome was born in spectacle, a very Texan sort of spectacle, tied to the state’s historical heritage and fascination with its own cowboy mythos. Yet even within the western milieu, the first modern dome celebrated innovation, hailing the feasibility of large-scale domes, the invention of Astroturf, and the most advanced scoreboard of its day. The building played host to a number of pop culture and exhibition events as significant as any of the baseball or football games played there.

On January 3, 1962, the seven Harris County commissioners, many wearing holsters and cowboy hats in the style popularized by men such as Vice President Lyndon Baines Johnson, stood on a small platform to perform the groundbreaking. The “Harris County Domed Stadium” was to be built on drained swampland. The men walked to the edge of the podium and, rather than use shovels, fired Colt .45 six shooters into the ground to break the first dirt.1 This homage to 1800’s frontier Texas launched the project but it would quickly take on a more forward-looking moniker, capturing the excitement of the space race. The new NASA manned spacecraft center being built in the south part of Houston would soon put American astronauts on the moon.2 This spectacular dichotomy of Texas western imagery and space-age technology became part of the Astrodome’s attraction.

The opening of the Astrodome occurred on April 9, 1965, with an exhibition game against the New York Yankees. The Astros, who changed their name from the Colt .45s in the offseason, won the exhibition 2–1 on a bloop single hit by Nellie Fox in the 12th inning.3,4

Mickey Mantle led off the game for the Yankees and hit the second pitch he saw from pitcher Dick Farrell, and in the fifth inning he hit a 400-foot home run to center field, giving the crowd what they wanted to see.5

However, to most attending that night, the game itself was irrelevant. The real attraction was the first indoor stadium. The ceremonial first pitch was thrown by Lyndon Johnson, the first time the opening pitch of a new stadium was made by a President of the United States.6 Following Johnson’s ceremonial pitch, 21 astronauts threw out 21 pitches, and later the “Gemini Twins” Gus Grissom and John Young joined the president and Texas Governor John Connally in the presidential suite.7

As for the players themselves, Mantle got lost in the service area beneath the Astrodome trying to find the clubhouse. He had planned to sit out the game due to injuries until he heard that President Johnson was in attendance and that he was slated to “be the first man to bat first in the baseball Taj Mahal of the Southwest.”8,9

Ross Moschitto commented that the Dome was “like an opera house.” Wordsmith Jim Bouton found it “fantastic—no, indescribable—no, science fiction.” Steve Hamilton was more concerned by the practical concerns of a major league ballplayer, asking, “Is it all right to chew tobacco here?”10

The Astrodome itself was crafted out of the hubris of Judge Roy Hofheinz. The anticipation for the opening had been building ever since Hofheinz stormed into the National League meeting in Chicago in 1960 concerning expansion and impressed the owners with his plans for a domed stadium, on the strength of which they awarded him and Houston one of the two available franchise slots (the other going to New York).11 Hofheinz was a character described as a “collaboration between Horatio Alger and Sinclair Lewis” while Texas author Larry McMurtry described him as “echt-Texas.”12,13

Hofheinz was born on April 10, 1912, and graduated from high school at the age of 16.14 Following his father’s death in a truck accident he started promoting dance bands in East Texas to support his family.15 While doing this he attended law school at night, passing the bar at age 19.16 He was elected as a representative to the state legislature at age 22, and at 24 he became the youngest man elected county judge of a major county. He spent 1948 running his friend Lyndon Baines Johnson’s successful senatorial bid, and at the age of 40 became Houston’s mayor.17

The Astrodome, and later the Astrodomain, was controlled by Judge Hofheinz beginning with his proposal to the National League owners in 1960, construction from 1962–65, and in the stadium’s daily operation until his health began to fail him in the 1970s. During construction the stadium acquired the nickname “Can-Do Cathedral” for overcoming obstacles such as multiple lawsuits and funding problems and still being completed six months early.18,19

Judge Hofheinz had installed many personal touches—most notably a three-story apartment above right field that he spent a significant amount of time living in.20 It featured a matching set of hand-carved six-foot high Thai temple dog statues, a gold-plated phone, and a 12-foot desk with black marble top that faced three televisions.21 And this was all before a guest actually entered the doors to the apartment. In addition to seats viewing the stadium, the apartment had a one-lane bowling alley, the Tipsy Tavern bar, velvet toilet seats, a personal movie theatre, a three-hole putting green, and a barbershop.22 Comedian Bob Hope, a friend of Hofheinz, described its style as “early King Farouk.”23

The indoor stadium was officially christened the Harris County Domed Stadium. However, this name was rarely used and everyone from Judge Hofheinz, the media, and the public simply referred to it as the Astrodome.24 Evangelist Billy Graham is often credited with coining the “Eighth Wonder of the World” epithet during his ten-day crusade in late November 1965; however, the Texas media had already been calling the Dome the “Eighth Wonder” back in April.25 The New York Times described the stadium prior to Opening Day by saying, “It stuns the eye with such dazzling splendor that even the natives, experts at the use of superlatives, find themselves groping for words in trying to describe this Eighth Wonder that has been created by their imagination, ingenuity and oil-soaked money,” and “this is a reluctant concession to chronology” since the “first seven on the tabulation have been wonders for centuries, but the Astrodome will not be formally opened until tomorrow night.”26

Between its opening in April of 1965 and December 28 of that same year, 402,712 people paid the $1 admission to tour the Astrodome.27 By the following year the Commerce Department’s Travel Service named it the country’s third most popular tourist attraction, following only the Golden Gate Bridge and Mount Rushmore.28,29 When these tourists, whether from across the country or across Houston, came to visit the Astrodome, their tour would be led by a young woman. She would seat the group in a section facing the field and begin by saying, “Welcome to the Astrodome. You are now seated in the world’s largest room.” The tour guide would then pause for several seconds to let the significance weigh on the assembled.30

The size and scale of the first domed stadium prompted write-ups from newspapers, magazines, and trade journals. The dome itself is “a steel trussed lamella-type trussed roof structure” that covers an area over nine acres and has an outer diameter of 710 feet while on the inside it is nearly half a mile around the outer concourse.31

The stadium radiated from second base out and directly above second the roof rose as high as 18 stories (202 feet), more than enough height for a young Bud Cort to soar in a homemade flying machine in the 1970 Robert Altman film Brewster McCloud.32 It also had the world’s largest parking lot, holding 30,000 cars, and over 45,000 deep-cushion “first class” theatre-style chairs arranged in continuous tiers of orange, red, and royal blue or as they described it on the tours, “vivid, zippy colors.”33

High above the seats where most fans sat, the Astrodome was the first stadium to feature luxury boxes, 53 of them, called Skyboxes.34 Two sets of stands on the field level were attached to tracks powered by motors to allow for the playing field to adjust from baseball to football.35 At 120 feet, the dugouts were the longest in baseball. As Hofheinz stated, “People like to go home and say they had seats behind the dugout. We can get 65 percent of our seats behind the dugout.”36 Hofheinz understood attracting crowds through spectacle. As he said at the end of 1965, “Our best advertisement is word of mouth, and that’s what we get when people come here and then go back to Timbuktu and brag about having been at the Taj Mahal.”37

Hofheinz’s approach led to criticisms over the years. In a New York Times travel piece from 1974, Gary Cartwright described the scale of the Astrodome as “confusing size and opulence with grandeur.”38 Architectural historian Stephen Fox described it as “one of the great monuments of American hubris in the 1960s in this kind of sense of no limits.”39

One feature of the Astrodome that was worthy of hubris, size, and opulence was the stadium’s scoreboard, which stretched across most of the outfield. It cost $2 million to construct and was described officially in the stadium’s tour book as “easily the world’s largest,” “an electronic marvel,” “giving patrons… more information, faster, than any visual display ever before seen,” and gave it size as “474 feet” long and “more than four stories high.”40,41 When an Astro hit a home run, the scoreboard would light up with an animation that featured snorting bulls, exploding six-guns, a cowboy whirling a lariat, dancing stars, and an unfurled Texas flag.42 After attending a game in 1965, author Larry McMurtry stated that “the game’s true function was to provide material for the man who operated the screen.”43 What McMurtry did not know was that the scoreboard required six operators.44

The centerpiece of the scoreboard, both literally and figuratively, was the Astrolite.45 It was a TV-style light screen that was the world’s largest screen at the time.46 Located directly in center field the Astrolite had a “seemingly endless repertoire of animated light pictures, story-board cartoons, or often simple one-word commands.”47 These commands were typically along the lines of “Charge” and “Olé.” However, after using the giant screen to broadcast commands such as “Kill the Umpire” and “We Wuz Robbed” the team’s management received a reprimand from the league president.48,49

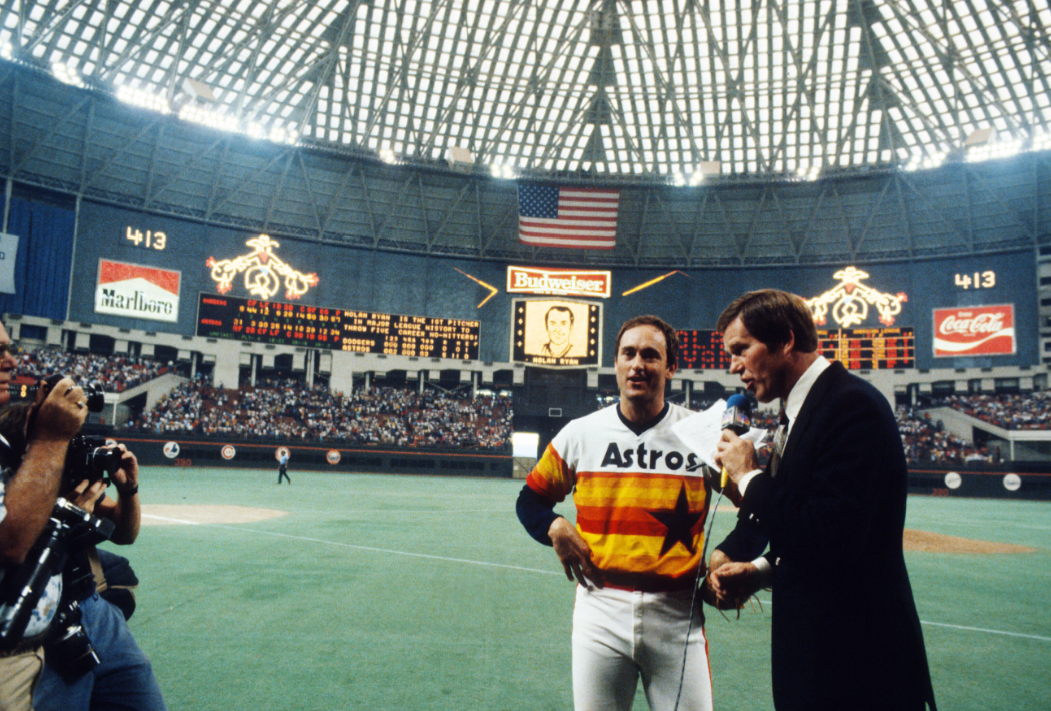

A highlight of the Astrodome was its 474-foot-long scoreboard, complete with a “seemingly endless repertoire of animated light pictures, story-board cartoons, or often simple one-word commands.” Here, the Astros congratulate Nolan Ryan on his 5th no-hitter in 1981.

The Astrolite is a prime example of Hofheinz’s naming convention, always space-related or incorporating the word Astro. Inside the Astrodome a visitor could eat at the Skyblazer Restaurant, Countdown Cafeteria, the Astrodome Club, or Domeskellar.50 This naming convention extended to the ownership group’s other business venture, the Astrodomain.51 A visitor from out of town could stay at the Astroworld Hotel, Astrodome Motor Inn, Holiday Inn–Astroworld, or Howard Johnson’s Motor Lodge–Astroworld.52 The Astroworld Hotel even featured the “two-level ‘Minidome Room’ nightclub that duplicates in miniature the Astrodome, even to a scoreboard” which sounds like a perfect venue to unwind after spending all day at a convention in the Astrohall convention center.53 For the kids there was Astroworld, an amusement park that was modeled to be become the Disneyland of the South, something it didn’t quite attain. If the kids were too distracted to watch the game, they could find themselves (provided their parents were friends with Judge Hofheinz) in the Astrotot Theater, Circus Room, and Playroom.54

Despite all its size and technological feats, “the Dome had only one relatively minor defect: it wasn’t very useful for playing baseball.”55 This led to the creation of the one still-used item from the Astrodomain with an Astro- name: Astroturf. The ceiling was built with 4,596 clear Lucite tiles to provide sunlight for the grass—Tiffway Bermuda grass tested at the Texas A&M College Experimental Station.56 There was little prior thought to how the Lucite tiles would magnify the sunlight and affect the outfielders.57 Fly balls would disappear somewhere around the dome’s third tier. Complaints began as early as the first exhibition game against the New York Yankees.

DuPont sent the Astros ten dozen baseballs that had been dyed yellow, orange, and cerise, as well as several shades of sunglasses to be issued to the players.58 Some outfielders began to wear chest protectors and batting helmets while they were in the field. Eventually the Astros painted over the Lucite which presented a new problem: the grass could not survive without sunlight. The outfield became a mess of dead grass, patched areas, and sawdust.59 Chemical company Monsanto Industries—somewhat ironically also the creators of the infamous defoliant Agent Orange—pitched a new synthetic playing surface called ChemGrass to Hofheinz.60

As the story goes, in early 1966 Monsanto sent a top salesman, armed with charts, drawings, renderings, and more. The salesman was nervous, and after he completed his pitch Hofheinz remained quiet. The salesman added 10 minutes’ worth of details before stopping again. Hofheinz was once again quiet. The salesman tried for 15 more minutes to add every previously unmentioned detail, sales hook, and more. When he was done Hofheinz asked “What’d you say it cost?” to which the salesman replied “$800,000.” After a long pause Hofheinz replied, “Funny thing. That’s just exactly what I was thinkin’ of charging you to let you call it Astroturf.”61

Whether Hofheinz’s encounter with the nervous salesman was true or a tall tale has been lost to history, but the team did get the plastic surface free in exchange for letting Monsanto have the name Astroturf. On April 18, 1966, the Astrodome had an Astroturf infield. By July 16 the Astros were playing their first games on a field that was completely covered in Astroturf. In 1970 five outdoor stadiums, Comiskey Park, Candlestick Park, Busch Stadium, Veterans Stadium, and Riverfront Stadium, became the next to install the artificial “grass,” which resembled a very short-pile shag rug.62 Many stadiums and playgrounds followed as well as the backyard of television’s Brady Bunch house.

The appearance of Astroturf in the backyard of The Brady Bunch wasn’t the only time the Astrodome or an aspect of it appeared on a television or theater screen. Throughout the 1970s, the dome was used as a setting for both popular sports comedies and forgettable television movies. The first and perhaps most interesting movie to prominently feature the Astrodome as a setting was Robert Altman’s Brewster McCloud, which was released in 1970.

The movie was Altman’s first release following his surprise hit M*A*S*H and in his review from December 1970, Roger Ebert described the film as “difficult,” “it may not have a narrative,” and concluded the review by saying, “I’m not sure it’s about anything.”63 And these observations were from a review that gave it 4.5 out of 5 stars. The plot is about an owlish young man named Brewster McCloud, played by Bud Cort, who lives in the depths of the Astrodome mechanical level. Under the guidance of a fallen angel (maybe) named Suzanne, McCloud builds a hand-powered flying machine. He also has interactions with a hot shot detective, a National Anthem-singing Houston socialite, and an elderly millionaire, but the supporting character that attracts the most attention is Shelly Duvall in her debut as Suzanne, a perky Astrodome tour guide who fancies herself an aspiring race car driver.

Current Sony Pictures Classics co-president Michael Barker wrote of growing up in south Dallas and how the movie “was highly anticipated in Texas because it was the first movie made in the Astrodome, that great modern Texas landmark” and that they realized while watching the film that “we are definitely not in the Texas of John Wayne.”64 The Astrodome itself played a prominent role in the movie, with many scenes set and filmed there: the socialite sings “The Star Spangled Banner” with a marching band behind her; Shelly Duvall gives the Astrodome tour to a group of tourists; numerous cat-and-mouse sequences as Brewster evades Dome security. In the spectacular closing, Brewster soars through the stadium in his flying machine with the authorities in pursuit, then crashes midfield while a large circus troupe enters through the center field gate and performs around the wreckage. The film’s premiere was held inside the Astrodome itself, with VIP seats on the actual turf.

The next film to feature the Astrodome was 1971’s Evel Knievel starring George Hamilton as the famous stuntman and motorcycle-jumper. The movie incorporated footage of Knievel’s real-life appearance at the Astrodome. On January 9, 1971, Knievel twice jumped 13 cars, breaking the record for an indoor motorcycle jump.65 The attendance for the two jumps totaled 99,000.

Also at the Astrodome, three years and one month later, the record Knievel had set was broken by Debbie Lawler, a 21-year-old petite blonde whose fans called her “The Flying Angel.” On the February 3, 1974, episode of ABC’s Wide World of Sports, Lawler jumped a total distance of 101 feet over 16 Chevrolet pickup trucks.66

In 1974 a movie entitled The Lord of the Universe was released to document the Millennium ’73 event that was hosted at the Astrodome by the teenage Guru Maharaj Ji, the prophet and leader of the Divine Light Mission religious group that many critics argued was a cult.67 The film details the preparation for the Millennium ’73 event, the devotion of the group’s followers, and their attempts to get close to the guru to gain “knowledge.” The film also gave screen time to critics including Abbie Hoffman, hare krishnas, and Houston-area Christian churches. The Divine Light Mission spent an estimated $1 million to rent the Astrodome from November 8 through November 10, 1973, and another estimated $500,000 on promotion for the event.68 Their advertising slogan was “Love is Free, Truth is Free, Admission is Free.” The Astrodome appealed to their astrological leanings from the very name Astrodome (and the Astrohall and Astroland Hotel). The guru they viewed as the celestial king was staying in the Celestial Suite, and the accents on the water faucets were swans, which the guru took to be his personal symbol. Premies, as the members of the group were called, spoke beforehand of how the event would be “the most important event in human history” and how “by November 15 the Astrodome will physically separate and fly from this earth” due to the power of the meditation within. Alas, this did not happen; the Houston Oilers were able to play a game the next day against Cleveland in an Astrodome still firmly planted on the same reclaimed swampland as before.

Millennium ’73 expected 100,000 attendees each day, but ended up with an estimated 20,000 for the entire event.69 The Lord of the Universe ends with a telling shot, beginning with the elaborate center-field stage on which the guru sat and then panning out until the stage is dwarfed by the Astrolite and scoreboard. The massive screen showed the Astros’ usual in-game fireworks display accompanying the guru’s message. A sparse crowd straggles through the outfield, and the stadium seats are nearly empty. The image was symbolic of the huge financial loss that began the organization’s decline.

There were two baseball-related releases in 1977. Murder at the World Series is a long-forgotten “movie of the week” television movie that premiered on March 20, 1977, on ABC.70 Bruce Boxleitner plays a revenge-minded pitcher cut from the Astros who pulls a series of kidnappings to hurt the Astros’ chance to beat the Oakland A’s. This would be the only time, imagined or real, that a World Series was filmed in the Astrodome. One critic described it as a “violent version of Nashville in which everyone is dull, mostly incompetent and associated with the Astros.”71 However that July a movie was released that better encapsulates the appeal of the Astrodome.

A surprise box office hit in 1976 was The Bad News Bears, a comedy in which the hard-drinking Walter Matthau manages an oddball collection of scrappy misfits on a Little League team. The sequel came out the following summer, part of a plan instituted by new Paramount executive Michael Eisner to turn the company’s struggles around. Eisner’s strategy was releasing movies with demonstrable money-making potential that could be made cheaply, movies which producer Don Simpson referred to as having to have a “cheeseburger heart.”72

The Bad News Bears in Breaking Training definitely had a cheeseburger heart. The movie had most of the team returning from the original, with the exception of the three most recognizable characters. Walter Matthau did not return as manager, Tatum O’Neal did not return as the girl pitcher, and Jeffery Louis Star had to replace Gary Lee Cavagnaro as Engelberg after Cavagnaro lost too much weight to play “the fat kid” in the year since the previous filming. This go round, the Bears are invited to play an exhibition game against a Houston team at the Astrodome. They take a long road trip from Southern California in a stolen van to get there, facing obstacles along the way, while the Bears’ star player and resident cool kid Kelly Leak reconnects with his father.

Though a line is tacked on about the winner getting to go to Japan (to set up the next sequel), the goal of the team is not to win a championship, not to beat a league rival, not even to get to play where the Houston Astros play, but to just get the chance to play an exhibition game in the Astrodome. This premise is displayed on the film’s advertisement and lobby posters, in which a banner hanging from the side of the team’s stolen van reads: “HOUSTON ASTRODOME OR BUST.”

There is a moment when, after driving all night, the team arrives in Houston and Leak wakes up the team so they can take in the Dome. Following some “oohs” and other excited comments, the Bears simply look at the stadium in awe. Later in the movie, following a difficult moment, Leak stands in his hotel room and opens a curtain, revealing the Astrodome to the camera and the audience.

The movie climaxes with a scene that potentially haunts Bud Selig. The Bears-Toros game is called because of time, so the scheduled Astros game that night can begin. As the Little Leaguers file off the field, an assortment of Houston Astros (including Bob Watson, J.R. Richard, Cesar Cedeño, and manager Bill Virdon) walk out in the vibrant mid-70s tequila sunrise uniforms. But feisty Bears shortstop Tanner Boyle refuses to leave the field. Bob Watson, the only Astro with a speaking part, notices and says, “Hey, let the kids play.”73 This chant is picked up first by the Bears manager, then the players, and eventually the whole Astrodome crowd is chanting “Let them play!” This same chant erupted at the 2002 All-Star Game in Milwaukee after Selig called the game off, tied 7–7 after 11 innings.

When it was not being used for baseball or football games or as a film set, the Astrodome hosted many other events and spectacles including rodeos, conventions, circus acts, and the first mid-air car crash. The first large non-sport event was a 10-day Billy Graham “Crusade for Christ” which began on November 19, 1965.74 President Lyndon Baines Johnson and Texas Governor John Connally were among the 61,000 who attended Graham’s opening night, setting an attendance record for the Astrodome that stood for years.75 The attendance for the 10-day event exceeded 600,000 and Graham sent a mixed message to Houston, declaring that the Dome was “a tribute to the boundless imagination of man” and also that “most Houstonians will spend an eternity in hell.”76

In its debut year of 1965, the Dome also hosted such diverse events as a boat show, a polo match, and a bloodless bullfight starring the legendary Spanish matador El Cordobes. The bloodless bullfights caught on and became a bit of a fad in mid-’60s Houston.77 As the Astrodomain expanded with the Astrohall and the various hotels, the number of conventions increased significantly. This expansion, especially the Astrohall, brought to the Astrodome what would be the longest running tenant of the stadium—not the Astros, but the Houston Livestock Show and Rodeo, who first used the venue on March 6, 1966, and returned every February/March through 2002.78

The rodeo became as well known for the nightly concerts as for the rodeo competition itself. Elvis Presley played a six-show stand at the Astrodome in 1970 with over 200,000 fans attending, and when he returned on March 3, 1974, Elvis set his single-show attendance record with 44,175 concert-goers. His previous single-concert record had also been set at the Astrodome, in 1970.79 On February 26, 1995, Tejano star Selena set a new Astrodome event attendance record at 61,041. This performance would be one of the singer’s last concerts prior to her murder.80 The final Houston Livestock Show & Rodeo concert would also be its largest, with 68,266 fans witnessing George Strait in his 16th performance at the Astrodome on March 3, 2002.81

One other sort of spectacle set an attendance record that lasted just shy of 11 months. On April 1, 2001, the World Wrestling Federation held the WrestleMania X-Seven, headlined by local wrestler Stone Cold Steve Austin and drew a crowd of 67,925.82 The first time the Astrodome hosted wrestling was when legendary local promoter Paul Boesch booked the arena in 1981 for two events headlined by the popular local wrestler Chief Wahoo McDaniel, one match against Dory Funk Jr. and later that summer against Professor Boris Malenko.83

That was not McDaniel’s first appearance in the Astrodome: on October 6, 1968, he was a middle linebacker for the Miami Dolphins. The Oilers had spent their early years playing at Rice Stadium, but had moved to the Dome that year. However, in 1974 when Super Bowl VIII was played in Houston, the game was held at Rice Stadium, which had 20,000 more seats. The first national sporting event to come through was in November of 1966 when Muhammad Ali defeated the local Cleveland “Big Cat” Williams by knockout in the third round.84 That night set the indoor boxing attendance record that stood for 25 years with a crowd that was 35,460 strong and grossed $461,290 which almost set the record for gross revenue at a boxing event.85 The most infamous boxing match at the Astrodome took place in December of 1982. Larry Holmes pummeled Tex Cobb in a mismatched affair that left Cobb bloodied. Sports Illustrated said the beat-down belonged “in the Alamo,” not the so-called Eighth Wonder of the World.86 The fight is also known for ringside announcer Howard Cosell vowing afterwards to never call another boxing match again in his career—a vow that he kept.87

The Astrodome hosted a 1968 game that many consider to have popularized college basketball and an NCAA Final Four Championship Tournament that was described as the most “odd” ever.88 In the “Game of the Century,” Kareem Abdul-Jabbar (then known as Lew Alcindor) and UCLA faced the University of Houston, led by stars Elvin Hayes and Don Chaney.89 UCLA at the time was riding a 47-game win streak and were the defending NCAA champions. The hometown UH beat UCLA by a score of 71–69 that January night in front of 52,693 fans. The contest received more national media attention than any prior college basketball game.90

Inspired by the success of that game, the NCAA choose the Astrodome to host the 1971 NCAA Final Four Basketball Championship.91 However a decision was made to place the court in the middle of the Dome yet have no floor seating around it. The placement created a vast expanse, a disconnect between the crowd and the action on the court, and a barren look on television.92 UCLA won the championship but officially only two teams are recognized as participating in the games. Later sanctions against Western Kentucky and Villanova, due to each team having players associated with professional agents, vacated the teams from the official NCAA record of the event.93

The sporting event hosted at the Astrodome that most etched itself into the memory of popular culture, though, was the exhibition tennis match on September 20, 1973, between female champion Billie Jean King and self-proclaimed “male chauvinist” Bobby Riggs in an event that was dubbed “The Battle of the Sexes.”94 Riggs had already been inducted into the International Tennis Hall of Fame and had won multiple championships in his career. However, his last championship had come almost 25 years prior to the match and he was 26 years older than his opponent, who was in the prime of her career. The 30,492 in attendance that night—still the largest attendance for a single tennis match in the United States—witnessed King carried Cleopatra-style into the Dome by members of the Rice University track team wearing togas, and Riggs arriving in a rickshaw pulled by a bevy of scantily clad women.95 An estimated 50 million people in the United States and another 40 million worldwide watched as King soundly defeated Riggs, leaving the brash man depressed for a considerable time afterwards.96 In addition to the prize money for the match, King scored a symbolic victory for women in sports, the effects of which are still felt today. Her performance made her an icon in the world of female athletics.97

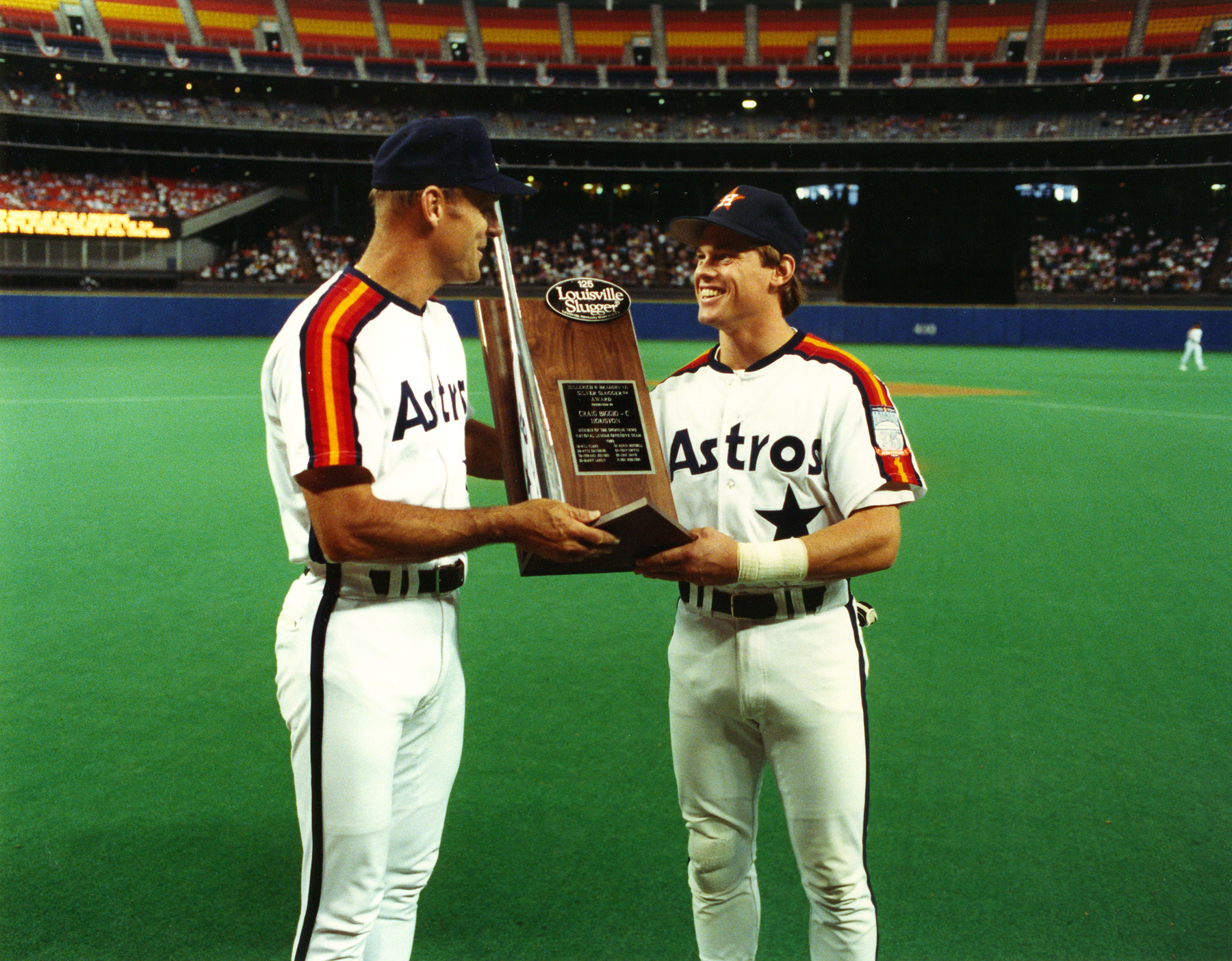

Houston Astros manager Art Howe, left, presents catcher Craig Biggio with his 1989 Silver Slugger award at the Astrodome.

Through the 1980s and ’90s the Astrodome began to lose some of its luster, as the newness wore off and newer domes, some of them even larger, began to pop up in New Orleans, Seattle, Indianapolis, Pontiac, Michigan, and elsewhere. National events suited to the domes spread to other cities and the Dome relied more on its core tenants of the Astros, Oilers, and Houston Livestock Show and Rodeo. In 1992, the Republican National Convention was held there. Judge Hofheinz had been hoping for a presidential convention ever since the Astrodome was built, and had even included a Presidential Suite in the design, with rugs featuring the presidential seal as part of the décor. During the time of the RNC, the Astros were forced to take a 26-game road trip, per the Secret Service’s request.

Citing the by-then outdated stadium and the dilapidated field conditions that had forced NFL officials to cancel a preseason game, the Houston Oilers left not just the Astrodome but Houston altogether and relocated to Tennessee for the 1997 season. In 2000 the Astros themselves left the Dome to begin play at Enron Field, now named Minute Maid Park. The Houston Livestock Show and Rodeo followed them in 2003. Concerts and high school football games were still held in the Dome for a while, but the presence of the newer and larger Reliant Stadium hurt the Dome significantly and in 2006 it was officially closed.

But in the months prior to that closing in 2006, the Astrodome managed to be a part of the national news one last time. Part of a large humanitarian effort by the city of Houston and the state of Texas, the Dome was the destination for 500 buses carrying refugees from New Orleans in the wake of Hurricane Katrina. On the morning of August 31, 2005, two days after the hurricane had made landfall, the convoy left the New Orleans Superdome, which had been severely damaged in the hurricane. More than 25,000 people were living in the Astrodome through September while they sought more permanent housing solutions.98

As of this writing, the city of Houston is still trying to determine what to do with the Astrodome. Few people refer to it as the Eighth Wonder of the World anymore and in comparison to Reliant Stadium next door it looks a bit drab. When asked about the Dome’s status in the pantheon of classic buildings, Neil deGrasse Tyson, astrophysicist and head of the Hayden Planetarium said, “When you’re in the present, you cannot judge what will become a wonder of the world, that’s to be judged by generations that follow. Here we are, ready to level the Astrodome, and the Pyramids are still standing.”99

However, even if the Harris County Domed Stadium is torn down at some point in the future, the mark the Dome leaves on pop culture and American history will not be so easily erased. Between movies, historic events, and the Dome’s historic firsts, while it might not match the Pyramids on the scale of world wonders, the Astrodome leaves us with a hell of a lot more memories than the Seattle Kingdome ever provided.

ERIC ROBINSON, a graduate of the University of North Texas, currently works in elementary education in Austin. He focuses his research on pre-MLB baseball history, Texas baseball history, and Central Texas blackball history, on which he has presented to local schools. Eric recently discovered his grandmother had a neighbor who played for the 1933 Brooklyn Dodgers. His website is www.lyndonbaseballjohnson.com.

Notes

1. Claude Charlier, “After a While, Nothing Seems Strange in a Stadium with a ‘Lid,’” Smithsonian, January, 1988.

2. “The Houston Astrodome Overview,” Housing the Spectacle, Dome Case Studies, www.columbia.edu/cu/gsapp/BT/DOMES/HOUSTON/ intro.html, Date accessed February 10, 2014.

3. Dene Hofheinz Mann, You Be the Judge (Houston: Premier Printing Company, 1965), 81.

4. Joseph Durso, “Astros Down Yanks 2–1, in First Major League Game Played Under Roof,” The New York Times, April 10, 1965.

5. Ibid.

6. Ibid.

7. Adam Chandler, “The Sad Fate (but Historic Legacy) of the Houston Astrodome,” The Atlantic, November 8, 2013, www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2013/11/the-sad-fate-but-historic-legacy-of-the-houston-astrodome/281269/, Date accessed February 18, 2014.

8. Ibid.

9. Al Reinert, “Greetings From the Eighth Wonder of the World: Happy Birthday, Dear Astrodome, Happy Birthday to You,” Texas Monthly, April 1975.

10. Durso, op. cit.

11. Mann, You Be the Judge, 80.

12. Reinert, op. cit.

13. Larry McMurtry, In a Narrow Grave: Essays on Texas (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1968) 109–17.

14. Mann, You Be the Judge, 13.

15. Reinert, op. cit.

16. Ibid.

17. Ibid.

18. Chandler, op, cit.

19. Ibid.

20. Mickey Herskowitz, “Dome Hits 30,” Houston Post, April 9, 1995.

21. Ibid.

22. Ibid.

23. J. Michael Kennedy, “7 Floors Decorated in ‘Early Farouk’: Hofheinz’s Gaudy Suite in Astrodome Being Razed,” Los Angeles Times, March 18, 1988, http://articles.latimes.com/1988-03-18/news/mn-1682_1_fred-hofheinz, Date accessed February 18, 2014.

24. “In Texas, Where Everything is Big, Houston Stadium is the Greatest,” The New York Times, December 6, 1994.

25. Robert Lipsyte, “The Astrodome Caps a Profitable Year,” The New York Times, December 31, 1965.

26. Arthur Daley, “Ball Park, Texas Style,” The New York Times, April 9, 1965.

27. Lipsyte, op. cit.

28. Chandler, op. cit.

29. Reinert, op. cit.

30. Ibid.

31. Louis O. Bass, A.M., “Unusual Dome Awaits Baseball Season in Houston,” Civil Engineering—ASCE, January 1965.

32. Ibid.

33. Reinert, op. cit.

34. Ibid.

35. Bass, op. cit.

36. Reinert, op. cit.

37. Lipsyte, op. cit.

38. Gary Cartwright, “There’s More Texas than Technology in the Houston Astrodome,” The New York Times, April 7, 1974.

39. Jim Yardley, “Last Innings at a Can-Do Cathedral,” The New York Times, October 3, 1999.

40. Herskowitz, op. cit.

41. Reinert, op. cit.

42. Herskowitz, op. cit.

43. McMurtry, op. cit.

44. Cartwright, op. cit.

45. Ibid.

46. Ibid.

47. Reinert, op. cit.

48. Cartwright, op. cit.

49. Reinert, op. cit.

50. McMurtry, op. cit.

51. Cartwright, op. cit.

52. Cartwright, op. cit.

53. Ibid.

54. Ibid.

55. Reinert, op. cit.

56. Bass, op. cit.

57. Dan Epstein, Big Hair and Plastic Grass (New York: Thomas Dunne Books, 2010), 48–50.

58. Durso, op. cit.

59. Reinert, op. cit.

60. Epstein, op. cit.

61. Reinert, op. cit.

62. Epstein, op. cit.

63. Roger Ebert, “Brewster McCloud,” rogerebert.com, www.rogerebert.com/ reviews/brewster-mccloud-1970, Date accessed February 20, 2014.

64. Michael Barker, “BREWSTER MCCLOUD; Faves, Hot and Cold,”

The New York Times, May 4, 2008.

65. Stuart Barker, Evel Knievel: Life of Evel (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2004), 95, 286.

66. Steve Mandich, “The Daredevil is a Woman,” stevemandich.com, www.stevemandich.com/evelincarnate/debbielawler.htm, Date accessed February 21, 2014.

67. Thorne Dreyer, “God Goes to the Astrodome,” Texas Monthly, January 1974.

68. Ibid.

69. Ibid.

70. Tom Keiser, “Sportsflicks: Taxi Driver (Of the Bullpen Car),” The Classical, October 30, 2013, http://theclassical.org/articles/sportsflicks-taxi-driver-of-the-bullpen-car, Date accessed February 21, 2014.

71. Ibid.

72. Josh Wilker, Deep Focus: Bad News Bears in Breaking Training (Berkeley: Soft Skull Press, 2011).

73. Ibid.

74. “Graham to Open Crusade in Houston’s Astrodome,” Ocala Star-Banner, November 19, 1965.

75. LBJ Hears Graham—Universal Newsreels, Internet Archive, www.archive.org, https://archive.org/details/1965-08-30_LBJ_Hears_Graham, Date accessed February 23, 2014.

76. Cartwright, op. cit.

77. J.R. Gonzales, “Dome of the Month: Bullfighting Under the Roof,” Houston Chronicle, April 30, 2012.

78. Jim Saye, “Show and Rodeo—The Houston Livestock Show and Rodeo: A Historical Perspective,” Houston History Magazine, January 2011.

79. Craig Hlavaty, “When Elvis Presley Came to Houston,” Houston Chronicle, August 16, 2013.

80. “Houston Livestock Show & Rodeo—16 Years Later,” Selena Legend, http://selenalegend.com/selena-live-at-the-houston-livestock-and-rodeo-show-16-years-later/, Date accessed February 23, 2014.

81. Saye, op. cit.

82. “WrestleMania X-7,” Pro Wrestling History, www.prowrestlinghistory.com/ supercards/usa/wwf/mania.html#17, Date accessed February 23, 2014.

83. G. Neri, “Wahoo! The Incredible Adventures of Chief Wahoo McDaniel: Wrestling Superstar,” Hunger Mountain—The VCFA Journal of the Arts, http://www.hungermtn.org/wahoo-the-incredible-adventures-of-chief-wahoo-mcdaniel-wrestling-superstar/, Date accessed, February 23, 2014.

84. Bert Randolph Sugar, “Greatest Knockouts: Ali vs. Williams,” espn.com, September 28, 2006, http://sports.espn.go.com/sports/boxing/news/ story?id=2606152, Date accessed February 23, 2014.

85. Ibid.

86. Pat Putnam, “He Took it All and Would Not Fall,” Sports Illustrated, December 6, 1982.

87. John Spong, “Randall “Tex” Cobb,” Texas Monthly, September 2001.

88. Mike Lopresti, “Houston’s Last Final Four: One Dome, Two Asterisks, and UCLA,” USA Today, March 13, 2011.

89. David Barron, “UH—UCLA Classic Played 43 Years Ago Elevated the Game,” Houston Chronicle, January 20, 2011.

90. Ibid.

91. Lopresti, op. cit.

92. Ibid.

93. Ibid.

94. Selena Roberts, A Necessary Spectacle: Billie Jean King, Bobby Riggs, and the Tennis Match that Leveled the Game (New York: Crown Publishers, 2005).

95. Ibid.

96. Ibid.

97. Ibid.

98. USA Today website, http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/news/nation/2005-08-31-astrodome_x.htm.

99. Chandler, op. cit.