Murder, Espionage, and Baseball: The 1934 All-American Tour of Japan

This article was written by Rob Fitts

This article was published in Nichibei Yakyu: US Tours of Japan, 1907-1958

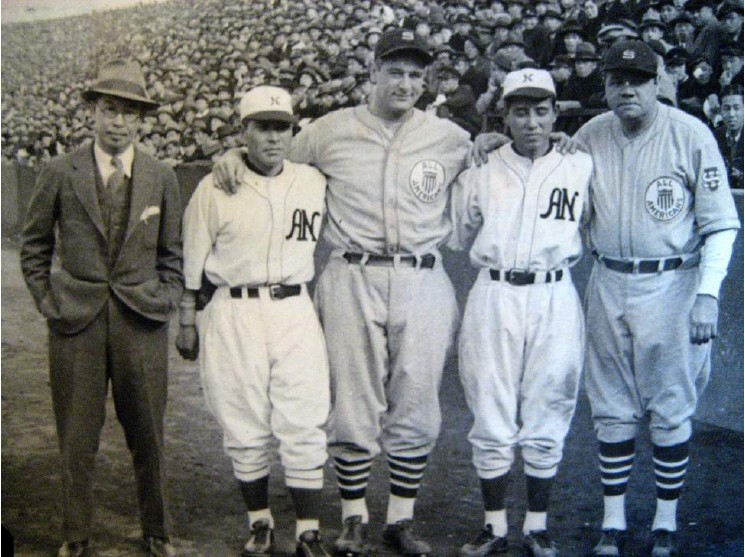

The 1934 All-Americans outside Nagoya Castle (Yoko Suzuki Collection)

Katsusuke Nagasaki’s breath billowed as he loitered outside the Yomiuri newspaper’s Tokyo offices. The morning of February 22, 1935 was chilly. But that was good; nobody would look twice at his bulky overcoat. Matsutaro Shoriki, the owner of the Yomiuri Shimbun, was late. Nagasaki strolled up and down the block, trying to remain inconspicuous.

Finally, at 8:40 A.M. a black sedan cruised down the street. Nagasaki halted in front of a bulletin board by the building’s entrance. He studied the announcements as a short, balding man with thick-framed glasses emerged from the car. As Shoriki began to climb the stairs into the building, Nagasaki strode forward, pulling a short samurai sword from beneath his coat. The blade flashed through the air, striking Shoriki’s head. The bloodied newspaper owner stumbled forward, as Nagasaki fled.2

Later that day, Nagasaki walked into a local police station and gave a detailed confession. The primary reason for the assassination attempt: Shoriki had defiled the memory of the Meiji Emperor by allowing Babe Ruth and his team of American all-stars to play in the stadium named in honor of the ruler.

Three months earlier, nearly a half-million Japanese had lined the streets of Tokyo to welcome the ballplayers to Japan. The players’ motorcade was led by Ruth in an open limousine. At 39, he had grown rotund, and just weeks before had agreed to part ways with the New York Yankees. But to the Japanese, he still represented the pinnacle of the baseball world. Sharing the car was his former teammate Lou Gehrig. The rest of the All-American baseball team, distributed three or four per car, followed: manager Connie Mack, Jimmie Foxx, Earl Averill, Charlie Gehringer, Lefty Gomez, Lefty O’Doul, and a gaggle of lesser-known stars.

Only one player didn’t seem to belong—a journeyman catcher with a .238 career batting average named Moe Berg. Although he was not an All-Star caliber player, his off-the-field skills would explain his inclusion on the team. Berg was a Princeton University and Columbia Law School graduate who had already visited Japan in 1932. He was multilingual, causing a teammate to joke that Berg could speak a dozen languages but couldn’t hit in any of them. Berg would eventually become an operative for the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the forerunner of the CIA, and many believe that the 1934 trip to Japan was his first mission as a spy.

The pressing crowd reduced the broad streets to narrow paths just wide enough for the limousines to pass. Confetti and streamers fluttered down from multistoried office buildings, as thousands waved Japanese and American flags and cheered wildly. “Banzai! Banzai, Babe Ruth!” echoed through the neighborhood. Reveling in the attention, the Bambino plucked flags from the crowd and stood in the back of the car waving a Japanese flag in his left hand and an American in his right. Finally, the crowd couldn’t contain itself and rushed into the street to be closer to the Babe. Traffic stood still for hours as Ruth shook hands with the multitude.3

Ruth and his teammates stayed in Japan for a month, playing 18 games in 12 cities. But there was more at stake than sport: Japan and the United States were slipping toward war as the two nations vied for control over China and naval supremacy in the Pacific. Politically Japan was in turmoil. From the 1880s through 1920s, Japan had enjoyed a form of democracy. This period saw great strides in modernization, a flourishing of the arts, and close ties to the United States. Yet, as Japan’s power grew, so did its nationalism. A growing minority of Japanese citizens felt that the country should take its place among the world powers by expanding its military and colonizing its neighbors. Ultranationalist societies began assassinating liberal politicians and members of the free press. By the early 1930s, the civilian government could no longer control elements of the military. In 1931 nationalistic officers engineered the invasion of Manchuria and twice plotted to overthrow the government. War between the United States and Japan seemed inevitable.

Politicians on both sides of the Pacific hoped that the goodwill generated by the tour and the two nations’ shared love of baseball could help heal their growing political differences. Many observers, therefore, considered the all-stars’ joyous reception significant. An article in the New York Times, for example, said, “The Babe’s big bulk today blotted out such unimportant things as international squabbles over oil and navies.”4 Connie Mack added that the tour was “one of the greatest peace measures in the history of nations.”5

Yet, not all Japanese wished the nations reunited. At the Imperial Japanese Army Academy, just two miles northwest of the parade, a group known as the Young Officers was planning a bloody coup d’etat, an upheaval that would jeopardize the tour’s success and put the players’ lives at risk. In another section of Tokyo, Nagasaki and his ultranationalist War Gods Society met at their dojo. Their actions would tarnish the tour with bloodshed.

The 1934 tour began not as a diplomatic mission but as a publicity stunt to attract readers to the Yomiuri Shimbun. Matsutaro Shoriki had purchased the financially troubled newspaper in 1924 and quickly turned it into Tokyo’s third-largest daily by increasing its entertainment sections.6

In 1931 Shoriki decided to bolster sports coverage by sponsoring a team of American all-stars to play in Japan. The team, which included Lou Gehrig, Lefty Grove, and five other future Hall of Famers, won each of the 17 games against Japanese university and amateur teams, and the newspaper’s circulation soared. But Shoriki wasn’t satisfied. The major-league team had lacked the greatest drawing card in baseball—Babe Ruth.

Shoriki immediately began organizing a second tour. Working closely with Sotaro Suzuki, a sportswriter who had lived in New York for nearly a decade, and National League batting champion Lefty O’Doul, Shoriki lined up the powerful 1934 squad. Most of the players’ wives accompanied their husbands on the trip, and the Ruths brought along their 18-year-old daughter, Julia. The tourists boarded the luxury liner Empress of Japan in Vancouver, British Columbia, on October 20 and, after a stop in Honolulu, arrived in Yokohama on November 2.

Although American teachers had introduced baseball in 1872, Japan didn’t have a professional league. To challenge the Americans, Shoriki brought together Japan’s best amateur players to form the All-Nippon team. The team included 11 future members of the Japanese Baseball Hall of Fame and numerous colorful personalities.

Two players, in particular, stood out. The first was hard to miss: 18-year-old Victor Starffin was the blondhaired, blue-eyed, 6-foot-3 son of a Russian military officer who had served Czar Nicholas II. During the Russian Revolution, the Starffins escaped by traveling in a freight train packed with typhoid patients, and later by hiding from the Red Army in a truck carrying corpses. After years on the run, the family settled in Japan. Young Victor fell in love with baseball and soon became a regional star. He hoped to play college ball, but in 1933 his father was convicted of killing a young Russian woman who worked in his teashop. The Yomiuri newspaper promised to use its influence to help Victor’s father if the young man would forsake college and play for the All-Nippon team.7

The All-Nippon squad also included a young American who hoped to become the first ethnic Japanese to make the major leagues. Jimmy Horio was born in Hawaii and left for California to follow his dreams at the age of 20. He played semipro for several years without breaking into Organized Baseball. Hearing that Shoriki was creating a team to challenge the visiting major leaguers, Horio traveled to Tokyo to try out. He hoped a stellar performance against the All-Americans would lead to a major-league contract. As a switch-hitter with power, Horio made the AllNippon team easily and hit cleanup, but would fail to impress the Americans.8

Over the next four weeks, the All-Americans and All-Nippon traveled together throughout Japan, visiting the northern island of Hokkaido; the industrial cities of Yokohama, Nagoya, and Osaka; the ancient capital of Kyoto; Kokura on the southern island of Kyushu; and, of course, Tokyo.

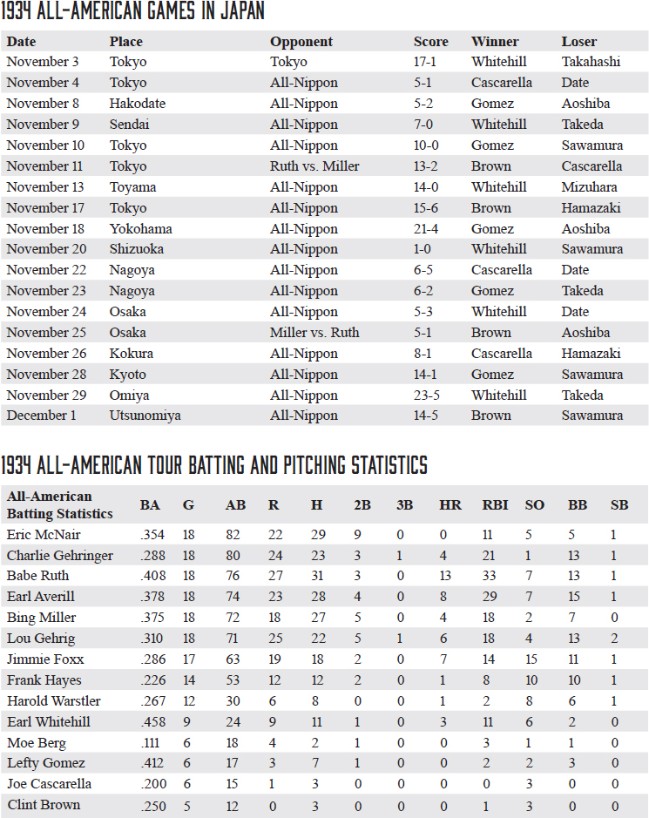

Sotaro Suzuki, unidentified All-Nippon player, Lou Gehrig, Hisanori Karita, and Babe Ruth (Yoko Suzuki Collection)

The tour began with two games at Tokyo’s Meiji Jingu Stadium. Prior to the games, fans camped out overnight to secure the best general-admission seats. They followed the Babe’s every move. A reporter stated, “The fans went crazy each time Ruth did anything—smiled, sneezed, or dropped a ball.”9 One old man brought a pair of high-powered binoculars, amusing himself and neighboring fans by focusing on the Bambino’s famous broad nose, making his nostrils fill the lens.10 Another fan, who worked in a textile factory designing kimono and undergarment patterns, had a novel plan. He would sit as close as possible to the field and study the Bambino’s face. He would memorize every feature, every wrinkle. Then he would return to the factory and create a pattern of the Babe’s face for a new line of Babe Ruth underwear. He was certain he would become rich.11

The Babe relished the attention and transformed into a comedian. During batting practice, he purposely missed some pitches—twisting himself around like a pretzel before falling over. Later, he began a game of shadow ball—hitting an imaginary grounder to Rabbit McNair at shortstop, who fielded it convincingly and started a double play, timed with perfect realism. The opening game itself was less interesting than Ruth’s antics. It pitted the All-Americans against the Tokyo Club, a team of recently graduated players from the Tokyo area, not the All-Nippon squad. It took just a few minutes for the fans, and players, to realize the difference in skill level between the two teams—the ball even sounded louder when coming off the American bats. The Americans seemed to score at will, pilling up 17 runs to Tokyo’s 1. To the crowd’s disappointment, none of the Americans hit a home run. Afterward, the Babe apologized for not going deep, telling reporters, “I was a little tired today, but tomorrow I will do my best to hit a home run.”12

The next day, November 4, the All-Americans played their first game against All-Nippon. It was the first time in history that true all-star teams representing the two countries clashed. Prior to the 1930s, visiting American professional teams were a mishmash of stars,journeymen, and minor-league players, and while the 1931 American club was a legitimate all-star team, it played only Japanese collegiate and company squads. The All-Nippon lineup featured six future Hall of Famers—Naotaka Makino, Hisanori Karita, Osamu Mihara, Minoru Yamashita, Jiro Kuji, and pitcher Masao Date. Although Date pitched “courageously,” and limited the All-Americans to five runs, the game’s outcome seemed inevitable.13 Jimmie Foxx, Lou Gehrig, and Earl Averill homered, with Averill going out twice. On the other side of the scorecard, American pitcher Joe Cascarella dominated the Japanese, giving up just three hits and walking only two.

Next, the All-Americans traveled north. As they boarded a ferry to cross the straits to reach Hokkaido, officials handed each traveler a small map with three coastal areas circled in red. Large cursive writing proclaimed, “Photographing, sketching, surveying, recording, flying over the fortified zone, without the authorization of the commanding officer of this fortress are strictly prohibited by order.” The handout was not an empty threat. Japan was paranoid about espionage, and officials even inspected Ruth during the trip to make sure that he wasn’t taking photographs. But neither the proscription nor the officials stopped Moe Berg. Defying the warning, Berg whipped out his camera and filmed the area.14

The teams played two games in the northern provinces, enduring bone-chilling winds and frosted fields. Once again, the Americans won comfortably. On November 8 in Hakodate, the All-Americans took control of the game minutes after the first pitch as Averill hit a two-out, first-inning grand slam. Meanwhile, Lefty Gomez dazzled the fans and opponents with both his speed and control. Up 5-1, manager Ruth brought in third baseman Jimmie Foxx to close out the game. The burly third baseman preserved the victory by allowing just one run in the final three innings. The following day in Sendai, Ruth went deep twice and Gehrig, Foxx, and Bing Miller each hit one out in a 7-0 American victory.

As the teams returned to Tokyo, two dozen army officers met at an isolated restaurant. Their purpose—to overthrow the Japanese government.

The Great Depression had hit rural Japan particularly hard, leading to widespread starvation. At the same time, large trading companies, known as zaibatsu, flourished due to the unstable markets and rampant inflation. The conspirators, led by Captain Koji Muranaka, belonged to the loosely organized Young Officers movement. The Young Officers felt that Japan’s government had betrayed its citizens by putting the interests of big business before the welfare of the populace. The group advocated the violent overthrow of civilian rule, the declaration of martial law, and the Emperor taking direct control of the government. The divine Emperor, they believed, would end rural poverty by redistributing wealth and would lead Japan to world prominence by conquering Asia.15

On November 27 Japan’s parliament would meet in a special session. Once the politicians gathered, the Young Officers and their troops planned to attack the Diet Building, slaughter the civilian government, and seize power. Other sympathetic troops would battle loyalist regiments in the streets of Tokyo. No mention was made of Babe Ruth and the ballplayers, but as the Imperial Hotel faced the Emperor’s palace and was just a few blocks from the Diet Building, Muranaka’s plan put the Americans in the line of fire.16

Meanwhile, the ballclubs stayed in the Tokyo area for 10 days, playing six games, attending banquets, and visiting the local tourist spots. The games were one-sided. The All-Americans won all six comfortably, scoring 60 runs while surrendering 12. The highlight came on November 10 at Meiji Jingu Stadium when Lefty Gomez, the man who claimed to have invented a rotating goldfish bowl to allow tired fish to rest, struck out 18 batters and pitched seven no-hit innings before surrendering two singles during a 10-0 American romp. A week later, on the 17th, All-Nippon grabbed their first lead of the tour by scoring three runs in the second inning. But tiny Shinji Hamazaki, the 5-foot-l former star hurler from Keio University, could not contain the American lineup. Gehrig homered to lead off the third inning and Foxx followed with the longest home run in the history of Meiji Jingu Stadium. The ball landed three-quarters up the high left-field bleachers, bounced once, and careened out of the stadium into the empty lot below. The All-Americans tacked on 13 additional runs off poor Hamazaki, who was left on the mound to suffer for the entire game. During the romp, Foxx played all nine positions and the portly Ruth even took a turn at shortstop.17

Throughout the tour, players and fans noted the differences between American and Japanese baseball. The two teams played and approached the game differently. Just as modern American baseball reflects its roots as a nineteenth-century urban game popularized during a time of industrialization, rapid economic growth, and mass immigration, the Japanese game, known as yakyu, reflects its origins in the cultural turmoil of the early Meiji period.

In the late 1880s, Japan struggled to establish its national identity. During the previous two decades it had transformed from a medieval society into a modern country with radically new political, economic, educational, and even social institutions. Many Japanese feared that the country was losing its native culture and abandoning time-honored traditions and values in favor of shallow materialism and frivolous Western fads. These concerns led to the philosophy of wakon yosai (meaning Japanese spirit, Western technology), the concept that Japan could import Western technology, institutions, and even ideas, but would imbue them with Japanese spirit. This philosophy may be illustrated best in baseball.

Although American teachers introduced baseball in the early 1870s, the distinctive approach that would characterize Japanese baseball for over 100 years developed in the early 1890s at Japan’s elite First Higher School, often called Ichiko. Following the concept of wakon yosai, the Ichiko players approached baseball as a martial art. “Sports came from the West,” a team member later explained. “In Ichiko baseball, we were playing sports but we were also putting the spirit of Japan into it. … Yakyu is a way to express the samurai spirit.”18

Ichiko’s brand of baseball, known as Spirit Baseball, emphasized unquestioning loyalty to the team as well as long hours of grueling practice to improve the players’ skills and mental endurance. Proponents of Spirit Baseball argued that a strong spirit could overcome physical shortcomings and lead to victory on the field. Thus, practices were designed to not only hone skills but also to develop mental fortitude through long, difficult drills that pushed players to their limits.19 Spirit Baseball offered hope to the All-Nippon team. Infielder Tokio Tominaga told reporters, “Many fans think that the small Japanese can never compete with the larger Americans, but I disagree. The Japanese are equal to the Americans in strength of spirit.”20

On November 20 a 17-year-old Japanese pitcher’s spirit was nearly strong enough to conquer the All-Americans. Aided by the midday sun in the batters’ eyes, Eiji Sawamura pitched the game of his life in the small town of Shizuoka at the foot of Mt. Fuji. He recorded 11 straight outs, including consecutive strikeouts of Gehringer, Ruth, Gehrig, and Foxx, before the Bambino broke up his no-hitter. The shutout continued until Gehrig homered in the seventh to give the Americans a 1-0 victory.21

The next morning, as the Japanese unfurled their newspapers and read the headlines, Sawamura became a national hero. Although the Japanese had not won, they showed that they were capable of conquering their opponents. The game would become a symbol of Japan’s struggles against the West. Many Japanese felt that with enough fighting spirit and practice, their countrymen could surpass the major leaguers, just as they believed their military would surpass the Western powers. As years passed, the importance of the game grew and Sawamura’s stature increased as he became a symbol of Imperial Japan. Today, Japan’s annual award for the best pitcher is called the Sawamura Award.

By November 20, Captain Koji Muranaka’s plans to seize control of Japan were almost ready. The special session of parliament was due to convene in seven days. Knowing that previous coup attempts had been betrayed from the inside, Muranaka had kept his group of assassins small. But Muranaka had not scrutinized his followers closely enough. Suspicious of Muranaka, the commander of the military academy had instructed a cadet to infiltrate the group and expose their plans.22

The same day as Eiji Sawamura pitched his masterpiece, the Kempeitai, Japan’s dreaded military police, arrested Muranaka and his conspirators. News of the plot remained hidden until the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal in 1946. Only a handful of men knew that bloodshed, revolt, and maybe even civil war, had nearly disrupted the All-American baseball tour.

Sawamura’s pitching masterpiece gave the AllNippon confidence as the two teams embarked on an eight-day, six-game junket in southern Japan. Their thousand-mile journey included stops in Nagoya, Osaka, Kokura, and Kyoto.

At Nagoya, the Japanese once again nearly upset the Americans, entering the bottom of the eighth with a 5-3 lead. Japanese starter Masao Date was visibly tired, but manager Daisuke Miyake elected to leave him in as the All-Americans scored three runs to take a 6-5 lead. Perhaps to give the All-Nippon a chance to win, the All-Americans brought in Jimmie Foxx to pitch the ninth. With one out, Isamu Fuma tripled into the right-center alley to put the tying runjust 90 feet away. Osamu Mihara, Waseda’s former star second baseman, was due up next. Mihara had just one hit and five strikeouts in 14 at-bats against the Americans, so Miyake decided to bring in the 5-foot-l pitcher Shinji Hamazaki to pinch-hit. Hamazaki was not inept with the bat. When not pitching for Keio University, he played the outfield and had hit .308 during the 1927 Big Six season. But still, it seems a strange choice. The All-Americans brought the infield in to defend against the squeeze and also prevent Fuma from scoring on a groundball. Hamazaki swung away and struck out. Mamoru Sugitaya, a solid outfielder with seven hits against the major leaguers, popped out to second to end the game. Both Lou Gehrig and the Japan Times criticized Miyake’s managerial decisions. Each felt that the Japanese might have won the game had Miyake brought in Sawamura in the eighth inning or had tried a squeeze play to score Fuma in the ninth.23 After the two close games, the All-Americans increased their focus and won the remaining six games easily with a combined score of 80-17.24

The November 26 game in Kokura provided one of the most enduring images of the tour. Driving rain had made the condition of the field laughable. Ankle-deep mud covered the dirt infield and pond-like puddles dotted the outfield. Normally, the game would have been canceled, but between 20,000 and 30,000 fans had squeezed into the tiny stadium to watch the American stars. Despite the rain, they had begun to arrive early in the morning, filling the seats hours before game time. The outfield contained no bleachers, just a grassy slope where spectators huddled together. The rains had flooded the area and 11,000 squatted or knelt with water up to their hips. Among the dedicated, wet fans sat a man with an ancient samurai sword. He had walked 80 miles to attend the game and announced that he would present the sword as a token of friendship to the first American to hit a home run.25

The game itself was a joke. Ruth, Gehrig, Averill, and Rabbit McNair played in rubber boots and Ruth—borrowing an umbrella from a fan—huddled under it while playing first base. The score remained 0-0 for the first three innings before the Americans started to hit. Three runs came across in the fourth and Averill won the sword by hitting a long fly into the soggy fans sitting beyond right field. An inning later with the bases loaded, Ruth stepped to the plate and dug in with his big rubber boots. The crowd laughed and began chanting, “Home Run! Home run!” According to Osamu Mihara, after the count went to 3-and-0, Ruth stepped out of the batter’s box and gestured to the fans that he would hit a home run. Shinji Hamazaki threw the next pitch down the middle and the Sultan of Swat connected with a mighty swing. The ball rose in a majestic arc and sailed over the right-field seating area and into the mist beyond. Initially stunned by the blast, the wet and happy fans erupted with a “tremendous ovation” for the Bambino.26 The All-Americans ended with 11 hits and eight runs, but the Osaka Mainichi noted that “they can hit almost at will” and would have hit many more “had they cared to run out every hit.”27 On the mound, Cascarella dominated the Japanese hitters with “baffling hooks and drops” as he scattered seven hits and gave up a single run for the 8-1 victory.28

Throughout the tour, Moe Berg left the group to explore on his own. Wherever he went, he took numerous pictures.

On November 29 Berg informed Connie Mack that he felt unwell and would miss the afternoon’s game. Immediately after the team left for the Omiya ballpark, Berg dressed in a black kimono, combed his hair in a Japanese style, and put on geta (traditional wooden sandals). It was just above freezing outside, so he probably slipped on an Inverness overcoat, concealed his 16-millimeter movie camera beneath it, and quietly left the hotel. He headed southeast through Ginza to St. Luke’s International Hospital, a tall structure with panoramic views of Tokyo.29

Pretending to visit the American ambassador’s daughter, Berg took the elevator to the top floor and climbed the spiraling staircase to the top of St. Luke’s 50-meter-tall tower. There, he pulled out his movie camera and panned the skyline, holding the camera still on a group of factories to the west and again on the waterfront. To cap off the footage, he focused on Mt. Fuji, just visible on the southwestern horizon.

During World War II, Berg became a spy for the OSS. He was even sent on a mission to assassinate Werner Heisenberg, the leading German physicist, if he had evidence that Heisenberg was close to creating an atomic weapon. Many believe that the trip to Japan was Berg’s first mission as a spy.30 But in truth, there is no evidence to support this claim other than Berg’s bizarre behavior.31 Personally, I believe that the 1934 Japan trip was a pivotal point in Berg’s espionage career. Not because it was his first mission, but because it sowed the seeds for his future career as a spy. It was while shooting clandestine pictures in Asia for the thrill that Berg realized his true calling.

By staying in Tokyo, Berg missed an opportunity to beef up his paltry .111 batting average. The ballpark at Omiya was small, holding just 8,000 spectators, with short outfield fences. The All-Americans wasted little time as they crashed home run after home run. By the end of the first, they were up 10-0. The barrage continued and with the Japanese down 23-5 in the bottom of the eighth, Miyake brought in 18-year-old Victor Starffin for his first, and only, appearance in the series. The young Russian was wild at first, walking Lou Gehrig and later Earl Averill, but both his fastball and curve were working well, and he struck out Jimmie Foxx between the two walks and induced Bing Miller to ground into a double play to end the inning. In all, the All-Americans hit 10 home runs—three by Gehringer, two apiece by Ruth and pitcher Earl Whitehill, and one each by Foxx, Gehrig, and catcher Frank Hayes.

The All-Americans played their last game on Japanese soil in Utsunomiya, a small city 60 miles north of Tokyo, on December 1. In recognition of his untiring efforts throughout the tour, Ruth named Sotaro Suzuki as the game’s manager. Suzuki was apprehensive as national hero Eiji Sawamura would start for All-Nippon. If the young hurler pitched well and the Americans relaxed and lost, people would blame him. The day was cold, so Suzuki set up a charcoal burner in the dugout for warmth. His apprehension grew as fans passed the Americans sake bottles and the ballplayers, who had adapted well to Japanese drinking customs, heated the liquor over the burner. Despite the alcohol, and a dropped fly ball by an inebriated Earl Averill, Suzuki had little to worry about. The Americans pounded out nine runs in the first four innings and the All-Americans went home 14-5 winners.32

On December 2 thousands of flag-waving fans crowded into Tokyo’s Ueno Station to say adieu. “Goodbye, Goodbye!” they shouted as Ruth sniffled and yelled “Sayonara, Sayonara! Banzai Japan!” Averill wept openly while Gehrig yelled, “See you again soon!” As the train readied for departure, the crowd quieted to hear Ruth’s final speech, “I don’t know how to show my appreciation, but if I have a chance I will come back,” he concluded.33 The train took the players to Kobe, where they boarded the Empress of Canada. They stopped briefly in Shanghai for a game against local all-stars, before finishing the tour with three games in Manila.

The success of the 1934 tour surprised American observers. Connie Mack found the Japanese “crazy about the great national game of America.”34 Capitalizing on the tour’s success, Shoriki kept the All-Nippon team intact and organized the professional Japanese Baseball League. Shoriki’s squad, renamed the Tokyo Yomiuri Giants, barnstormed in North America in 1935 and 1936, and went on to dominate the Japanese league for decades.

As the All-Americans left Japan, Americans and moderate Japanese proclaimed the goodwill tour a diplomatic success. Prince Iyesato Tokugawa, a direct descendant of the shogun who had united Japan in 1603, stated, “Between two great peoples able really to understand and enjoy baseball there are no national differences which cannot be solved in a spirit of sportsmanship.”35

According to The Sporting News, Connie Mack summed up the consensus when he said that the trip did “more for better understanding between Japanese and Americans than all the diplomatic exchanges ever accomplished.”36 Furthermore, Mack assured listeners “that there would be no war between the United States and Japan.”37

The Sporting News added, “[W]e believe that the recent trip to the Orient of baseball’s finest has served to delay, if not prevent, any possible conflict. We like to believe that countries having such a common interest in a great sport would rather fight it out on the diamond than on the battle field.”38

It did not take long, however, for that feeling to vanish.

Several weeks after the ballplayers departed on the Empress of Canada, Japan pulled out of the Washington Naval Treaty, which had limited the size of the major powers’ navies. Two months later, Katsusuke Nagasaki attacked Shoriki. Details of Captain Koji Muranaka’s failed coup were not made public, but a military tribunal held in March 1935 let the rebels off with a six-month suspension from active duty.

A year later, on February 26, 1936, Muranaka joined 23 other Young Officers in a violent rebellion that assassinated several high-ranking government officials and narrowly missed the prime minister. Rival military units crushed the rebels and arrested their leaders. Nineteen, including Muranaka, were executed. Despite the coup’s failure, the events led to a series of civilian governments more sympathetic to the military’s nationalist agenda.39 In July 1937 Japan invaded China. Whatever hope there had been for reconciliation between the United States and Japan vanished. Ultimately, the two countries’ love for baseball could not overcome Japan’s desire for regional dominance.

During the war, the military seized control of professional baseball. The fascists outlawed English baseball terms and redesigned uniforms to imitate military styles. Many members of the All-Nippon team served in the military and several, including Eiji Sawamura, lost their lives. Instead of chanting “Banzai Babe Ruth,” Japanese infantry screamed “To hell with Babe Ruth!” as they charged to their deaths in the jungles of the South Pacific.40

Yet, the goodwill tour was not a complete failure. Several of the friendships cemented during the 1934 visit survived the war and helped reconcile the two nations. Lefty O’Doul, who remained close to both Shoriki and Sotaro Suzuki, traveled to Japan at his own expense in 1946 to renew the friendships and help restart Japanese baseball. Three years later, O’Doul organized the first of several baseball tours held during the Allied occupation. Once again, baseball was used as a diplomatic tool to help bring the nations closer together, but this time with lasting success.41

ROBERT K. FITTS is the author of numerous articles and seven books on Japanese baseball and Japanese baseball cards. Fitts is the founder of SABR’s Asian Baseball Committee and a recipient of the society’s 2013 Seymour Medal for Best Baseball Book of 2012; the 2019 McFarland-SABR Baseball Research Award; the 2012 Doug Pappas Award for best oral research presentation at the annual convention; and the 2006 and 2021 SABR Research Awards. He has twice been a finalist for the Casey Award and has received two silver medals at the Independent Publisher Book Awards. While living in Tokyo in 1993-94, Fitts began collecting Japanese baseball cards and now runs Robs Japanese Cards LLC. Information on Rob’s work is available at RobFitts.com.

NOTES

1 Adapted from Robert K. Fitts, “Murder, Espionage, and Baseball: The 1934 All-American Tour of Japan,” NINE: A Journal of Baseball History and Culture Volume 21, No. 1 (Fall 2012): i-ii, by permission of the University of Nebraska Press.

2 Details from Nagasaki’s attack on Shoriki are drawn from Shinichi Sano, Kyo-kaiden: A Century of Matsutaro Shoriki and His Kagemushas [in Japanese] (Tokyo: Bungei Shunju, 1994); Associated Press, “‘Patriot’ Stabs Noted Publisher in Tokyo for Sponsoring Babe Ruth’s Tour in Japan,” New York Times, February 22, 1935: 1; “President of Yomiuri Attacked and Injured,” Osaka Main, February 23, 1935: 2; “Slashed by Sword, Yomiuri President Victim of Attack,” Japan Times, February 23, J935: 1-2; Yomiuri Shimbun, February 23, 1935: 1. Shoriki survived the attack and after 50 days in a hospital returned to work.

3 Stuart Bell, “Japan Belongs to Babe,” Cleveland Press, November 23, 1934: 44; “Babe Ruth Comes with Strong U.S. Baseball Team,” Japan Times, November 2, 1934: 1-2.

4 Associated Press, “Tokyo Gives Ruth Royal Welcome,” New York Times, November 3, 1934: 9.

5 “Mack Hails Ruth as Peace Promoter,” New York Times, January 6, 1935: s7.

6 Edward Uhlan and Dana L. Thomas, Shoriki: Miracle Man of Japan (New York: Exposition Press, 1957).

7 Natasha Starffin, Glory and Dream on a White Ball: My Father V. Starffin [in Japanese] (Tokyo: Baseball Magazine, 1979); John Berry, The Gaijin Pitcher: The Life and Times of Victor Starffin (LaVergne, Tennessee: CreateSpace, 2010).

8 Yoichi Nagata, Jimmy Horio and U.S./Japan Baseball: A Social History of Baseball [in Japanese] (Osaka: Toho Shuppan, 1994).

9 Naoki Fujio, “1934 Tour,” Yakyukai 25, no. 3 (1935): 184.

10 Fujio.

11 “Baseball Battle U.S.-Japan Madness!” Yomiuri Shimbun, November 5, 1934: 3.

12 “Baseball Battle U.S.-Japan Madness!”

13 Associated Press, “U.S. Stars Hit 4 Home Runs in Japan; Idolized Ruth Fails,” Washington Post, November 6, 1934: 17.

14 John Quinn, 1934 Tour Scrapbook, private collection.

15 This simplified summary of the Young Officers’ position is based on Delmer Brown, Nationalism in Japan (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1955); Ben-Ami Shillony, Revolt in Japan (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1973); and Christopher W.A. Szpilman, “Kita Ikki and the Politics of Coercion,” Modern Asian Studies 36, no. 2 (May 2002): 467-90.

16 Details of Muranaka’s plans are based on accounts written after World War II. For a discussion of the 1934 plan see H.G. Schenck, Brocade Banner: The Story of Japanese Nationalism (Washington: General HQ Far East Command Military Intelligence Section, 1946), 67-68; Shillony, 45-46; Royal Jules Wald, The Young Officers Movement in Japan, ca. 1925-1937: Ideology and Actions (Ann Arbor: University Microfilms, 1949), 168-69.

17 “Americans Rout All-Japan Nine; Ruth Hits Homers,” Japan Times, November 18, 1934: 1.

18 Quoted from the introduction of Yakyu Bushi Fukisoku Dai Ichi Koto Gakko Koyukai (Tokyo, 1903), translated by Robert Whiting and reprinted in Whiting, The Samurai Way of Baseball (New York: Warner Books, 2005), 6.

19 Robert Whiting, “The Samurai Way of Baseball and the National Character Debate,” The Asian-Pacific Journal:Japan Focus (September 2006).

20 Tokio Tominaga “Interview,” Yakyukai 25, no. 1 (1935): 138.

21 “Americans Beat All-Japan Nine By 1-0 Score,” Japan Times, November 21, 1934: 5; “Sawamura Permits Americans 1 Run,” Osaka Mainichi, November 21, 1934: 3; Sotaro Suzuki, Sawamura Eiji: The Eternal Great Pitcher [in Japanese] (Tokyo: Kobunsha, 1982), 75-77; Eiji Sawamura, “Interview,” Yakyukai 25, no. 1 (1935): 160-61; “Big Pitcher Battle,” Yomiuri Shimbun, November 20, 1934: 5.

22 Details of how the plot was discovered are fragmentary and sometimes contradictory. See Wald, 168-69; Shillony, 45-46; and Schenck, 67-68.

23 Suzuki, Sawamura, 93-94.

24 Suzuki, Sawamura, 93-94.

25 John Quinn, “American League Stars Tour Far East,” Spalding Official Base Ball Guide 1935 (Chicago: A.G. Spalding 1935), 264-65; Sotaro Suzuki, Unofficial History of Japanese Professional Baseball [in Japanese] (Tokyo: Baseball Magazine, 1976).

26 Osamu Mihara, My Baseball Life [in Japanese] (Tokyo: Toashuppan, 1947).

27 “Ruth, Averill Knock Home Runs at Kokura,” Osaka Mainichi, November 28, 1934.

28 “Ruth Hits Homer With 3 Men On,” Japan Times, November 28, 1934: 5.

29 The description of Berg’s visit to St. Luke’s is taken from Nicholas Dawidoff, The Catcher Was a Spy (New York: Vintage Books, 1995), 94-95.

30 Louis Kaufman, Barbara Fitzgerald, and Tom Sewell, Moe Berg: Athlete, Scholar, Spy (Boston: Little Brown, 1974).

31 Dawidoff; Robert K. Fitts, Banzai Babe Ruth (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2012).

32 Suzuki, Unofficial History, 258.

33 “U.S.-Japan Baseball Games Are Over,” Yomiuri Shimbun, December 2, 1934: 5.

34 Connie Mack, My 66 Years in the Big Leagues (Philadelphia: Universal House, 1950), 58.

35 “America-Japan Society Honors Baseball Players,” Japan Times, November 16, 1934: 2; Associated Press, “Calls Baseball Bond Between U.S.[,] Japan,” New York Times, November 16, 1934: 29; “Baseball Stressed as Trans-Pacific Tie,” Japan Advertiser, November 16, 1934.

36 “Tourists Prove Benefits of Jaunts,” The Sporting News, January 17, 1935: 4.

37 >“Scribes Honor Mack, Dizzy Dean, Maranville,” The Sporting News, February 7, 1935: 1.

38 “Stifling Good-Will Tours,” The Sporting News, January 3, 1935: 4.

39 Shillony, 147-48.

40 Associated Press, “’To Hell with Babe Ruth, Yell Charging Japanese,” New York Times, March 3, 1944: 2.

41 William N. Dahlberg, “A Tool for Diplomacy: Baseball in Occupied Japan 1945-1952” (paper presented at SABR 40, Atlanta, August 6, 2010); John Gripentrog, “The Transnational Pastime: Baseball and American Perceptions of Japan in the 1930s,” Diplomatic History 34, no. 2 (2010): 247-73.