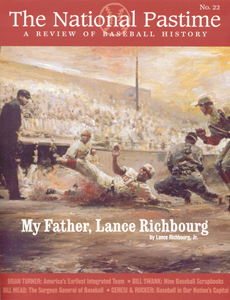

My Father, Lance Richbourg

This article was written by Lance Richbourg Jr.

This article was published in The National Pastime (Volume 22, 2002)

In 1951 my father, Lance Richbourg, was named one of three outfielders on the all-time Boston Braves team. He was the regular right fielder and leadoff hitter for the Braves in the late 1920s, batting .308 over the course of eight seasons in the majors. Perhaps just as impressive is his lifetime .328 batting average in a minor league career that spanned nearly two decades. But for many fans my father’s most distinguishing characteristic was his gentlemanly demeanor. Several years ago, I received a letter from an elderly man who was six years old when he started going to baseball games in Milwaukee. His mother attended games on Ladies Day and said that Lance Richbourg was her favorite player because ”he didn’t wipe his nose on his sleeve like the others.”

In 1951 my father, Lance Richbourg, was named one of three outfielders on the all-time Boston Braves team. He was the regular right fielder and leadoff hitter for the Braves in the late 1920s, batting .308 over the course of eight seasons in the majors. Perhaps just as impressive is his lifetime .328 batting average in a minor league career that spanned nearly two decades. But for many fans my father’s most distinguishing characteristic was his gentlemanly demeanor. Several years ago, I received a letter from an elderly man who was six years old when he started going to baseball games in Milwaukee. His mother attended games on Ladies Day and said that Lance Richbourg was her favorite player because ”he didn’t wipe his nose on his sleeve like the others.”

When my father was born in 1897, northwest Florida was a vast forest of yellow pine. A person could not wrap his arms completely around the trunk of any of those great trees that had stood in place so long, there was no underbrush. The forest was as clean as a park and one could see for a quarter-mile. By the time my father was playing in the majors, that forest had been devastated: first, by turpentine workers who drained the gum by cutting deep, cup-like wells in the tree’s trunk; then by lumber mills that leveled the woodland. My father took the destruction of that forest as a personal loss. For the rest of his life he had an abiding reverence for the pine tree and a crusading zeal for conservation and reforestation, an environmental consciousness that was years ahead of its time. The depth of his feeling impressed on me what an awesome place that old forest must have been.

The details of family history leading up to my father’s birth are pieced haphazardly in my mind, based on memories of tales I heard when growing up. Recently, a relative in Georgia informed me that research on the family had established the identity of its progenitor in America: one Claude Phillippe de Richebourg, the pastor of a Huguenot church who arrived in Virginia in 1690 and had migrated to Santee, South Carolina, by the time of his death in 1718. The Richbourgs’ connection to the Huguenots, a Protestant sect that was persecuted in 17th-century France, as well as their connection to South Carolina and cattle, had been a part of family lore for as long as I can remember. The economic function of Georgia and the Carolinas in the 18th century was to provide food for slave plantations on the sugar-producing islands of the Caribbean, and South Carolina’s main product was beef.

By the late 19th century, a handful of South Carolina families had drifted down to northwest Florida, the Richbourgs among them. Those cattle clans managed their herds simply by turning them loose in the forest.

The cattle grazed in low places along the river branches and swamps, becoming nearly as wild as deer. Their range extended from Crestview, Florida, to the northwest shore of Choctawatchee Bay, an area about the size of Rhode Island. Every so often, a bunch of cows would be gathered up and herded to a railhead in Florala, Alabama, where they were sold off for a nickel a head. “But it was all profit,” my father would hasten to add.

Those periodic round-ups were called “cow hunts.” They were carried out by men and boys mounted on skinny horses riding in U.S. Army cavalry saddles, the most minimal and cheapest of gear, and using dogs with powerful jaws that would clamp down on a cow’s muzzle and hold it in place. There were celebrated dogs and horses whose names are lost in the fog of time, but one I do remember was Dillard, a horse renowned for his quickness and skill as a cow pony, as well as his longevity—some 18 years in service. For weeks at a time, the cow hunters lived in the forest in pursuit of cattle. To me, as a boy hearing those tales, it all sounded like a huge, glorious camping trip, compounded by the romance and excitement of careering through the wild on horseback. But my Uncle Clint, who had been born into the final days of cow-hunt life, used to shake his head and mutter about the absurdity of riding a horse for fun.

Once my father took sick while out on a hunt. For a couple of days, he could barely sit on his horse. When my grandfather finally noticed his boy’s indisposition, all he said was, “Son, you don’t look so good. You’d better go home.” Going home meant a 20-hour ride through the forest—alone. When my father finally reached his destination, he spent the next two months in bed with some unnamed fever. No one knew what it was, though he nearly died of it. I thought to ask him how old he was at the time: “Twelve,” he replied.

My father told of riding through the forest from cow-hunt encampments to play in ball games. When he was about 16, he went to boarding school in Defuniak Springs, Florida, and played baseball there. He spoke of a teacher, a woman who was in charge of the school’s athletics, who told him he had the ability to play baseball for a living. Volume II of SABR’s Minor League Baseball Stars lists Lance Richbourg as having played in the Dixie League with Dothan, Alabama, as early as 1916. He is listed as having played 48 games for Newport News of the Virginia League in 1918, which must have occurred while he was in the Navy because I have discharge papers dated December 7 of that year. After his discharge, my father enrolled at the University of Florida. A story he liked to tell was of standing on the porch and watching the festivities of his fraternity’s dance through a window because all he had to wear was his navy issue.

In the spring of 1919, my father lettered in baseball and was discovered and signed by the New York Giants. It came about like this: The Giants were working their way north after spring training, playing exhibition games along the way. One was in Gainesville against the University of Florida team, and beforehand the college president addressed the team. “Who knows but someday one of you might wear the colors of the New York Giants,” he said. One story has it that my father, playing third base, charged in on batter Heinie Zimmerman, expecting a bunt. Instead, Zimmerman lashed a line drive that my father miraculously gloved. As dramatic as that anecdote is, it seems he would have needed to perform deeds of more consequence—perhaps lining a couple of his signature triples—to catch the eye of John McGraw. Whatever my father did, the next day he was sitting in the bleachers watching the Giants work out when the legendary manager approached him and said, “Son, did you ever consider a career in professional baseball?” McGraw signed him then and there for $250 per month, which my father took to be all the money in the world.

That summer he went up to New York. The intra-team competition was so ferocious, he told me, that McGraw would have to clear the way so my father could get in a few swings during batting practice. ‘Those old veterans weren’t going to make some kid who might take their job feel welcome to it,’ my father said. He never did get into a game that season, and the next he tested McGraw’s patience by not reporting until his college term was done in May (he eventually earned a B.S. in agriculture in 1922). As a consequence, the Giants farmed him out to Grand Rapids, where he hit .415 in 87 games.

The next year, in 1921, McGraw sent him to the Philadelphia Phillies in a trade for Casey Stengel. Reporters considered it crazy to trade the “fleet-footed Richbourg” for the “clumsy Stengel,” but Casey went on to become a World Series hero for the Giants while my father played only ten games for the Phillies.

In 1923 my father, playing for the Nashville Vols, was enjoying a fantastic season. He and Kiki Cuyler composed two-thirds of what sportswriters were calling the best outfield ever in the Southern Association. It was broken up in midseason, however, when my father, batting .378 at the time, split the large bone in his lower left leg while sliding into third, beating out a triple. The Nashville Tennessean wrote, ‘If somebody had to break his leg, why couldn’t it be Warren G. Harding or the King of Spain?’ Just days earlier my father had been purchased by the Washington Senators, and the injury seriously interrupted the trajectory of his career. While Cuyler moved on to Pittsburgh in 1924, capitalizing on his prime to build a Hall of Fame career, my father reported to the Senators, not fully healed. Washington had Goose Goslin in left field and Sam Rice in center, but right field was up for grabs; nonetheless, my father was unable to beat out the likes of Nemo Leibold, George Fisher, and Carr Smith. The Senators ended up sending him to Milwaukee in a deal for Wid Matthews, and that third outfield slot eventually fell to Earl McNeely, whose famous “pebble hit” won the seventh game of the 1924 World Series.

In 1975, my father recollected his final at-bat with the Senators to Ed Barfield of the Pensacola News Journal: “We were playing Boston in Washington and were tied up 2-2 in the bottom of the ninth. Bucky Harris, our manager, had told us before the last inning that if our leadoff hitter, Muddy Ruel, got on base, then Fred Marberry, our pitcher, would have two swings to bunt him down. If he were to fail after two strikes, then I was to pinch-hit. Well, Ruel got on base, Marberry got two strikes on him trying to bunt, and I came in to pinch-hit. The count got to 3-2, and then I lined one over the third baseman’s head just fair for a triple. We won 3-2. As I was walking up the long ramp from the dugout, Harris came up, slapped me on the back, and said: “Way to hit the ball, kid. Pack your bags, you’re going to Milwaukee.”

That story serves well to invest the narrative of my father’s career with drama and bittersweet irony, but it never really occurred. The game that comes closest took place in Detroit on June 4, only a few days before his release when he pinch-hit and drove home the go-ahead run in the top of the eighth inning. The Tigers, however, scored in their half of the eighth and eventually won the game in extra innings. In the mind of my father—as scrupulous a person as anyone I’ve ever known—that story had become the truth. That he had come to believe it, in my opinion, shows the measure of his pain in failing to hang on with a team that became world champions.

My father had three solid seasons with Milwaukee. In 1926, he had a standout year, leading the American Association in runs, hits, triples, and stolen bases. From 1927 to 1931, he played right field for the Boston Braves, posting his best season in 1928 when he batted .337 and ranked fourth in the National League with 206 hits.

Because my father was a left-handed batter and fast, he often bunted for hits. He practiced throughout the season, spending mornings in Boston trying to place bunts into a cap that his partner, an old pitcher, would move around the infield. Once, playing in Cincinnati, opposed by Hall of Fame pitcher Eppa Rixey, my father laid down a bunt that rolled backward.

In the eighth inning and eventually won the game in extra innings. In the mind of my father—as scrupulous a person as anyone I’ve ever known—that story had become the truth. That he had come to believe it, in my opinion, shows the measure of his pain in failing to hang on with a team that became world champions.

Catcher Bubbles Hargrave charged blindly over the ball. When my father got to first base, he looked back and saw the ball sitting in the center of home plate—reportedly the shortest base hit in the history of baseball. On May 14, 1927, Lance Richbourg made it into baseball’s official record book—as well as Ripley’s Believe It or Not—by playing right field throughout 18 innings of a doubleheader without a single fielding chance, thereby setting the standard for a single day’s idleness. On July 31, 1929, my father entered the record book again when he hit three triples in one game, tying the major league mark.

I have a newspaper clipping in which Paul Shannon of the Boston Post describes my father snagging a scorching line drive in his bare hand. “By way of a desperate spring, he managed to intercept the sphere though he took it over his head,” Shannon wrote. “The ball landed squarely on the tips of the fingers of his “Meat Hand.”‘ The article goes on to describe my father finishing that game and playing through the second game of the doubleheader, though he was seen to shake his hand after swinging and many of the spectators figured he must have been hit by a foul tip. X-rays after the game showed that his finger had been broken at the top joint. I remember that there was not a single straight finger on either of my father’s hands; apparently, they all had been broken at one time. Another Shannon clipping describes Richbourg as a “brittle type of athlete.” When I asked my father about that remark, he said, “I just took chances those other guys wouldn’t take.” One of those chances came in 1931 when my father ran into the outfield wall while chasing a fly ball. The resulting injuries limited him to 97 games that season, and his .287 batting average was his lowest with the Braves. That December he was traded to the Chicago Cubs.

One time in Chicago, my father and some teammates were taken to a restaurant, something of a private club from his description. Upon seeing a couple of dark, dapper gents across the room, their host quickly made his way over to their table and introduced them to his ballplayer guests. One of those gentlemen was “Legs” Capone, Al’s brother. “I had to let them know who you were,” their host explained, “otherwise they might bomb my store or something.” After 44 games with the Cubs, my father was sent down to the International League, where he batted .371 in 75 games. “There is no greater gulf than the gulf between the major and the minor leagues,” my father used to say. He was called back to Chicago in September, but not in time to be eligible for the 1932 World Series, when Babe Ruth supposedly made his famous “called shot.”

After the Series, Cincinnati acquired my father, who refused to report when the Reds tried to send him back to the International League with Rochester. Henceforth he was sold to his old team from bittersweet 1923, the Nashville Vols, and in midseason 1935, he was named player-manager. “Richbourg is too much a gentleman to be a successful manager,” wrote one reporter when he was fired at season’s end, but he was soon rehired and continued as player-manager in Nashville through the 1937 season.

In 1938, he received a similar appointment in Richmond, Virginia, where I was born at the end of the season. My birth marked the end of my father’s playing career in organized baseball. After managing one more season in Richmond, he bought a ranch near Ft. Pierce, Florida, merging it with a much larger ranch owned by Alto Adams, a boyhood friend and successful lawyer who was soon appointed to the Florida Supreme Court and later ran unsuccessfully for governor. For a few years, my father managed the 20,000-acre ranch, also managing the Ft. Pierce baseball team in his spare time.

By the mid-1940s, my father was in charge of the Farm Security Program at Escambia Farms, Florida. That program helped returning World War II veterans acquire small farms, with a new house, barn, and mule composing the package to get them going raising cotton, corn, or peanuts. Perched on a little rise behind the Escambia Farms General Store, my father’s office was a small prefab house identical to those on the veterans’ farms, and that place, as well as the drives out dusty farm roads to visit FSP farmers, form some of my earliest memories involve the knowledge my father had gained from his lifelong experience working with cattle, a valuable resource in a community without a large animal veterinarian. Once, a full-grown stallion was brought to our house for my father to castrate, and when my mother asked, “Can you castrate a horse?” he confidently replied, “I can castrate anything.”

In 1948, my father was elected County Superintendent of Education in a landslide victory of 5,281 to 1,226, reflecting both his popularity and, possibly, dissatisfaction with the incumbent. When he took office, the school system faced financial challenges, and my father’s frugality brought it back to financial health within two and a half years. During his 16-year tenure, 17 new schools were constructed, and the operating budget grew from $900,000 to $7,428,000. Upon my father’s retirement in 1964, U.S. Representative Bob Sikes telegrammed, “I can think of no finer tribute to a man in Public Life than to say he gave every fiber of his being to the job.”

My father turned his full attention to the Crestview ranch, which had been homesteaded by his family generations before. I worked with him during the last years of his life, finding the ranch as a break-even proposition but rewarding if raising cattle was one’s passion, as it was for my father. He had a keen knowledge of each of the 200 cows in the herd. When the calves came, for instance, he always knew which calf belonged to which cow, though it took me several weeks. to learn, and even then, I could never match them all. We worked many long hard days together. His stamina and energy seemed youthful, which might have been an effect of his lifelong discipline to hard work. My father claimed to take a teaspoon of turpentine every day in winter to ward off colds, and he never had any serious illness.

When I left the ranch in 1975 to take a teaching job in Vermont, my father decided to cut back the herd. Early in the morning of September 10, he loaded a truck with cattle to send to market. After he got them all aboard, he sat down next to the cattle chute and died. He was 77 years old.

Shortly thereafter, Red Barber, the famous radio voice of the Brooklyn Dodgers, remembered my father in his column in the Tallahassee newspaper:

“I only saw him once and at a distance. It was at a ball game in a small town and in a very small ballpark. It was just an exhibition game in the spring of 1927. The Boston Braves were playing the then-minor league Milwaukee Brewers in Sanford, Florida. This man I saw that one afternoon took my eye every time a fly ball was hit to his area. He was slender, and he moved with a fluid, certain grace. It was a joy to watch him judge where a ball would come down, glide to the spot and with a soft yet sure hand catch the ball. …

“Years later Branch Rickey explained what I had seen and would see many, many times in the big cities of the land—in his phrase, ‘the pleasing skills of the professional.’ And it came back to me in a flash when and where I first became in any way aware of it: 1927, Sanford, watching Lance Richbourg play the outfield.”

Dubbed by one critic as “America’s foremost baseball artist,” LANCE RICHBOURG JR. is an art professor at St. Michael’s College in Colchester, Vermont, and a member of the Gardner-Waterman Chapter of SABR. His work is represented by O.K. Harris gallery in New York City. The author wishes to thank Tom Simon and Elaine Segal for their editorial assistance.