NAPBL Gathering in Miami Gave Birth to the Caribbean Series

This article was written by Lou Hernandez

This article was published in The National Pastime: Baseball in the Sunshine State (Miami, 2016)

The 46th National Association of Professional Baseball Leagues winter meeting took place in Miami during the first days of December 1947. The convention was held at the McAllister Hotel, located on the corner of East Flagler Street and Biscayne Boulevard in the heart of downtown. Upon its completion a quarter century earlier, the ten-story “ultra-modern high-rise” boasted 300 rooms, all with private baths.

Many of those rooms offered scenic views of Biscayne Bay, just a few hundred feet to the east. Guests in these pricier rooms could have witnessed from their balconies the assassination attempt of President-Elect Franklin Roosevelt in early 1933 after he delivered a speech at Bayfront Park, directly across the street from the McAllister. Only a few years before the NAPBL gathering, the hotel served as ritzy housing for wartime enlisted men in the US Navy. By this time, the McAllister had been expanded to 550 rooms with two additional wings.

The once-grand hotel would be razed in 1988, making room for a steel skyscraper, but that was still four decades away at the time more than 1,500 attendees—1,200 registered baseball delegates and 300 diamond officials and players—descended on Miami for the NABPL gathering. The sleepy southern town did not disappoint its Chamber of Commerce, with clear skies and balmy temperatures in the 70s throughout the representatives’ days-long stay. “News stories filed with Western Union by the approximately 100 writers attending the sessions totaled a half million words,” according to one estimate. “Besides press service, a non-profit service was established to record programs direct from the scene for rebroadcast.”1

So what was the hot news that winter that generated so much copy? Baseball, on all its broad circuit levels, was booming, following its second prosperous season after World War II. But the growth was being achieved perhaps too rapidly, at least at the non-major league level. George Trautman, the president of the National Association, urged caution in an opening statement to the convention. “As of now the association with 54 leagues and 388 teams is a growing concern,” said the minor league czar. “Our main job is not to seek additional leagues but to strengthen all of our existing leagues.”2

One minor league in particular was seeking to better its station among its many peers. “The coast league is asking the right to be called the Pacific Coast Major League,” alerted one communiqué, “[while] still remaining part of the minor league organization. However, it would be under the direct jurisdiction of Commissioner Happy Chandler and the major league executive council.”3 The PCL’s petition to be recognized as a third major league, or “super minor circuit,” did not receive the required voting support from its constituents for the self-aggrandizing proposal to pass. (Falling short of the required three-quarters majority, 32 of the 54 leagues voted in favor of the PCL’s desire.)

A measure all leagues did come to an agreement on was the adopting of a uniform baseball throughout the minor leagues, beginning in 1949. Currently, the lower-circuit balls were said to be more lively than the balls used in the majors and therefore did not gauge a prospect’s talent accurately.

The Philadelphia Phillies backed a (failed) amendment to eliminate the “bonus baby rule” less than a year since its inception. “The Phillies had paid $55,000 for [pitcher] Curt Simmons,” explained one source, “who cannot be farmed out unless every other club is offered a chance at his contract for $10,000.”4

If the Internet had existed 70 years ago, without question, the biggest trending topic from the entire conference would have occurred on December 3. It would have involved the apparent pending resolution of suspended Brooklyn Dodgers manager Leo Durocher. Dodgers president Branch Rickey was holding talks with Commissioner Happy Chandler, who had suspended Durocher the preceding April for association with unsavory types detrimental to baseball. New York writer Roscoe McGowen captured the prevailing news sentiment with his filed story that day: “From Miami, Fla., where practically all of major league baseball are assembled to attend the minor league meetings, the sole topic of conversation yesterday was Rickey and Durocher, and there was considerable sentiment in favor of the return of the manager.”5 In only a few days, after the conclusion of the convention, Durocher would be reinstated by Chandler and allowed to take the reins of the NL champion Dodgers for the 1948 campaign.

Durocher would be overseeing a team that had been the first to champion integration in the sport in the previous season. The Dodgers had decided to train in Panama and Cuba to shield their pioneer black player, Jackie Robinson, in 1947. But with a new scheduling eye on more traditional spring training locales for 1948, the team and player must have been greatly heartened by another newspaper account from the Sunshine State: “An interesting development was information pointing unmistakably to a sharp revision of racial feelings against the Dodgers’ Jackie Robinson in many sections of the Deep South and Southwest. No Florida town has offered to pull out the welcome mat for the Flock if Robinson appears in the lineup. Not only have the Dodgers been invited to play exhibitions in Georgia, Texas and Oklahoma, but each invitation has been accompanied by a special request that the Negro star appear in the lineup.”6

Among the baseball executives and players in Miami were New York City’s other two current baseball pilots, Bucky Harris of the New York Yankees and Mel Ott of the New York Giants. Both failed in their open attempts to land new players for their teams. A deal to secure Early Wynn and/or Walt Masterson from the Washington Nationals fell through on the Yankees skipper. Mel Ott struck out in trying to land Johnny Van der Meer from the Cincinnati Reds. Ott also turned down an offer from the Phillies for any one of their four starting pitchers in exchange for rookie hurler Clint Hartung.

Baseball Commissioner Happy Chandler, one of the many attendees to the 1947 conclave in Miami. (National Baseball Hall of Fame Library)

Another manager with a New York affiliation came into town from the unusual southern direction. “Lefty Gomez, former southpaw ace of the Yankees who managed their Binghamton farm club last summer,” identified one report, “flew in from Cuba, where he is managing Cienfuegos, a name he has difficulty in spelling. However, he had the translation for it, ‘one hundred fires—and believe me, when we lose they build half of them right under my seat.’”7

Cienfuegos was one of the four teams of the Cuban Winter League that had joined Organized Baseball earlier in the calendar year as an “unclassified affiliate” of the National Association. That initiation—spurred from the fallout of the player war between OB and the Mexican League’s Jorge Pasquel in 1946—turned out to be a historic one for international winter baseball, as this press release from the Magic City stated: “Prospects of a Pan-American World’s Series among the champions of Panama, Puerto Rico, Venezuela and Cuba—details of which remained to be worked out—brightened as a result of conferences between representatives of those countries and the National Association here.”8

The Sporting News went so far as to hail the agreement in its December 10, 1947, issue’s editorial page:

At the minor leagues’ convention in Miami last week, representatives of leagues in Venezuela, the Republic of Panama, and Puerto Rico expressed their intention of joining Cuba under the protective wing of the National Association, with the privileges which this will bring. Among these privileges are the right to use designated players from American minor leagues during the winter season, and a non-raiding agreement with other countries.

Much credit is due Trautman, the National Association, and Commissioner A.B. Chandler, for taking the initial steps toward closer relations between the game in this country and our Latin American neighbors.

Eventually, perhaps, the majors might even establish farm clubs in Latin American leagues and uncover future big-time prospects among native talent.9

Four months later in Havana, on April 12, 1948, an accord was created between officials from Cuba, Panama, and Puerto Rico, to establish La Confederación de Baseball Profesional del Caribe, with an initiative for a fourth country, Venezuela, to join, which the country shortly thereafter accepted. The Caribbean Professional Baseball Federation, comprising the Latin American Winter Leagues, created the original plans for the Caribbean Series, to take place at the close of the following winter season.

The new Latin American baseball championship tournament was realized with the inauguration of the first Serie del Caribe on February 20, 1949. Held at Gran Stadium del Cerro de la Habana, the double-round-robin competition showcased championship teams from four Caribbean basin winter league nations. The opening ceremonies featured players from all the teams filing out toward the center field flagpole to raise their own country’s colors. Walter Mulbry, representing Commissioner Chandler’s office, hoisted the flag of the Confederación del Caribe to punctuate the history-making occasion. George Trautman threw the ceremonial first pitch.

Pitcher Pat Scantlebury recorded the first win in Caribbean Series history, a 13–9 victory over Puerto Rico’s Mayagüez Indios, in the first of two games played on that date. The Canal Zone native, pitching the distance for the Spur Cola Colonites, benefited from strong run support in throwing the 16-hit triumph. (The contest, apparently running long, was purposely shortened to eight innings, so as not to interfere with the start time of the second game of the evening.) In the nightcap, Dalmiro Finol of Cervecería Caracas, slugged the initial Caribbean Series home run. The Venezuelan’s blast accounted for the only run for his Andean team, which was embarrassed 16–1 by the Almendares Scorpions of Cuba. Conrado “Connie” Marrero cruised to the four-hit win.

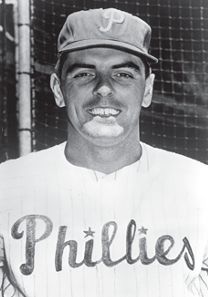

The Phillies hoped in vain to have the “bonus baby” rule lifted so they could offer pitcher Curt Simmons (pictured here) to other teams for more than the required $10,000. (National Baseball Hall of Fame Library)

Marrero’s Almendares club went on to win the first tournament with an undefeated 6–0 record. Scorpions left fielder Al Gionfriddo became the first person to play in a World Series and Caribbean Series and hit for the highest average in the competition: .533 (8 for 15). Outfield mate Monte Irvin led all hitters with 11 RBIs. Marrero’s pitching cohort, Agapito Mayor, was named first MVP of the Series. The left-handed Mayor won three games, including two in relief.

George Trautman proclaimed the tournament a success although not one of the six day’s cards produced a sellout, and the overall attendance remained lower than expected. Part of his closing statement read:

The first Caribbean series will be remembered for many years to come as the realization of the dream of baseball leaders of Cuba, Panama, Puerto Rico, and Venezuela. The 1949 series has proven the possibility of using the game’s good neighbor policy to tighten friendship ties.

Cuba can consider itself proud of the work it has done in this series. The new Havana Stadium is one of the best baseball parks in the world. The four contenders of the first Caribbean series have been true contenders and have been guided by excellent sportsmanship.10

Teams from Cuba won seven out of the first twelve Caribbean Classics played. (Each country alternated hosting the games.) Talented squads from Puerto Rico took home the championship trophy four times, including 1955, with its native club featuring 23-year-old Willie Mays. Panama City’s Carta Vieja Yankees captured the Caribbean crown in 1950. Following the 1960 competition, the tournament was interrupted. Cuban dictator Fidel Castro abolished all professional sports on the island and expropriated hundreds of millions of dollars in US and Cuban citizens’ property. Included in the totalitarian usurpation was Gran Stadium, which was the first million-dollar baseball stadium erected in Latin America and had been built by Cuban businessmen Miguelito Suárez Jr. and Bobby Maduro. The stadium, renamed “Latinoamericano,” is still considered the main baseball venue in Cuba today.

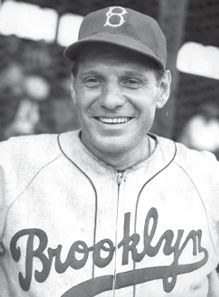

The fate of Leo Durocher was a hot topic in Miami and he was reinstated a few days after the end of the meeting. (National Baseball Hall of Fame Library)

After a ten-year absence, the Caribbean Series was revived in February of 1970. Original members Puerto Rico and Venezuela were joined by a new national associate from the Dominican Republic. Played in Caracas, the Magallanes Navegantes, the home nation’s team, delighted the faithful by capturing Venezuela’s first Caribbean Series championship with a 7–1 record.

In 1971, Mexico’s Naranjeros of Hermosillo joined the other national squads as a fourth representative, returning the tournament to its original 24-game, double-round-robin format. Five championship series later, in 1976, Hermosillo brought back the first Caribbean Series title to Mexico, posting a 5–1 record. Superstar slugger Héctor Espino was selected the tournament’s MVP.

In 1990 and 1991, the Series was ceded to Miami. It was played in the Orange Bowl in the former year and Bobby Maduro Stadium the next. Neither showcases financially warranted playing another in the US.

The Latin American baseball championship tournament progressed as an annual event into the twenty-first century. The exception was 1981, when the Caribbean Series did not materialize due to an owners and players’ dispute over the distribution of gate proceeds and meal money.

The 56th edition of the Caribbean Series, held on the isle of Margarita in Venezuela, opened the way for the reintegration of a Cuban national team. In 2014, with US State Department pre-approval, Cuba’s Villa Clara Naranjas appeared in the reformatted five-team competition, where there are two rounds of play and the team with the best record is not guaranteed the championship hardware.

The 2016 Caribbean Series was held at Estadio Quisqueya, the Dominican winter home of the Licey Tigers—the team that has won the most Caribbean Series championships with ten. Juan Marichal threw out the ceremonial first pitch. The former great pitcher was bestowed with an honorary recognition by the tournament. “When you think about all that he has done for baseball and the Dominican Republic, we wanted to dedicate this great event to Mr. Marichal,” Caribbean Confederation commissioner Juan Francisco Puello Herrera said on the eve of the event. “He has brought so much pride to the country on so many levels. Every host country has the option to dedicate the tournament, and Marichal was an excellent choice to represent the Dominican Republic.”11

Mexican representative Venados de Mazatlán (the Mazatlán Deer) won the 2016 Series in the most dramatic fashion. In the championship game versus Venezuela’s Aragua Tigers, February 7, Mazatlán’s DH Jorge Vásquez smacked a leadoff, walk-off home run in the bottom of the ninth inning to lift the team to a thrilling 5-4 championship victory. The win gave the Venados a perfect 6–0 mark in the seven-day competition and conferred the fourth Caribbean Series crown in six years to a Mexican squad.

LOU HERNÁNDEZ is the author of several baseball histories. He resides in South Florida and roots for the Marlins.

Sources

Buddy Nevins. “The End Of An Era.” Sun Sentinel, January 6, 1988.

Monte Cely. Serie del Caribe 2016 in Santo Domingo. Society for American Baseball Research.

“The McAlister Was City’s First High-Rise.” Miami Archives

The Caribbean Series. Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1. “1,200 Register For The Convention.” The Sporting News, December 10, 1947, 5.

2. “Minors Are Urged Not to Expand, But to Bolster Existing Leagues.” The New York Times, December 2, 1947, 41.

3. AP. “Baseball Moguls Opening Annual Meeting in Miami.” The Post-Standard, December 1, 1947, 10.

4. Ibid.

5. Roscoe McGowen. “Rickey Talks With Chandler, Naming of Dodger Pilot Near.” The New York Times, December 4, 1947, 48.

6. John Drebinger. “International League Provisionally Approves Coast’s Quest of Major League Status.” The New York Times, December 2, 1947, 41.

7. Roscoe McGowen. “Rickey Talks With Chandler, Naming of Dodger Pilot Near.” The New York Times, December 4, 1947, 48.

8. Edgar G. Brands. “Latin American Nations Flock to O.B. Banner.” The Sporting News, December 10, 1947, 7. The idea for the Caribbean Series was originated by Venezuelan promoters Oscar “El Negro” Prieto and Pablo Morales, according to contemporary reports circulated by Wikipedia and Baseball-Reference.com. The author was unable to find any specific, dated information to corroborate this. Both Internet sources mentioned appear to have confused the NAPBL meeting in Miami in 1947 with the Caribbean Professional Baseball Federation’s establishment in Havana, four months later.

9. “Majors Can Aid Latin American Unity.” The Sporting News, December 10, 1947, 12.

10. Pedro Galiana. “ ’50 Caribbean Series to Puerto Rico; Bigger Split Arranged For Players.” The Sporting News, March 9, 1949, 28.

11. Jesse Sánchez. “Caribbean Series begins Monday with balanced field.” MLB.com, January 29, 2016.