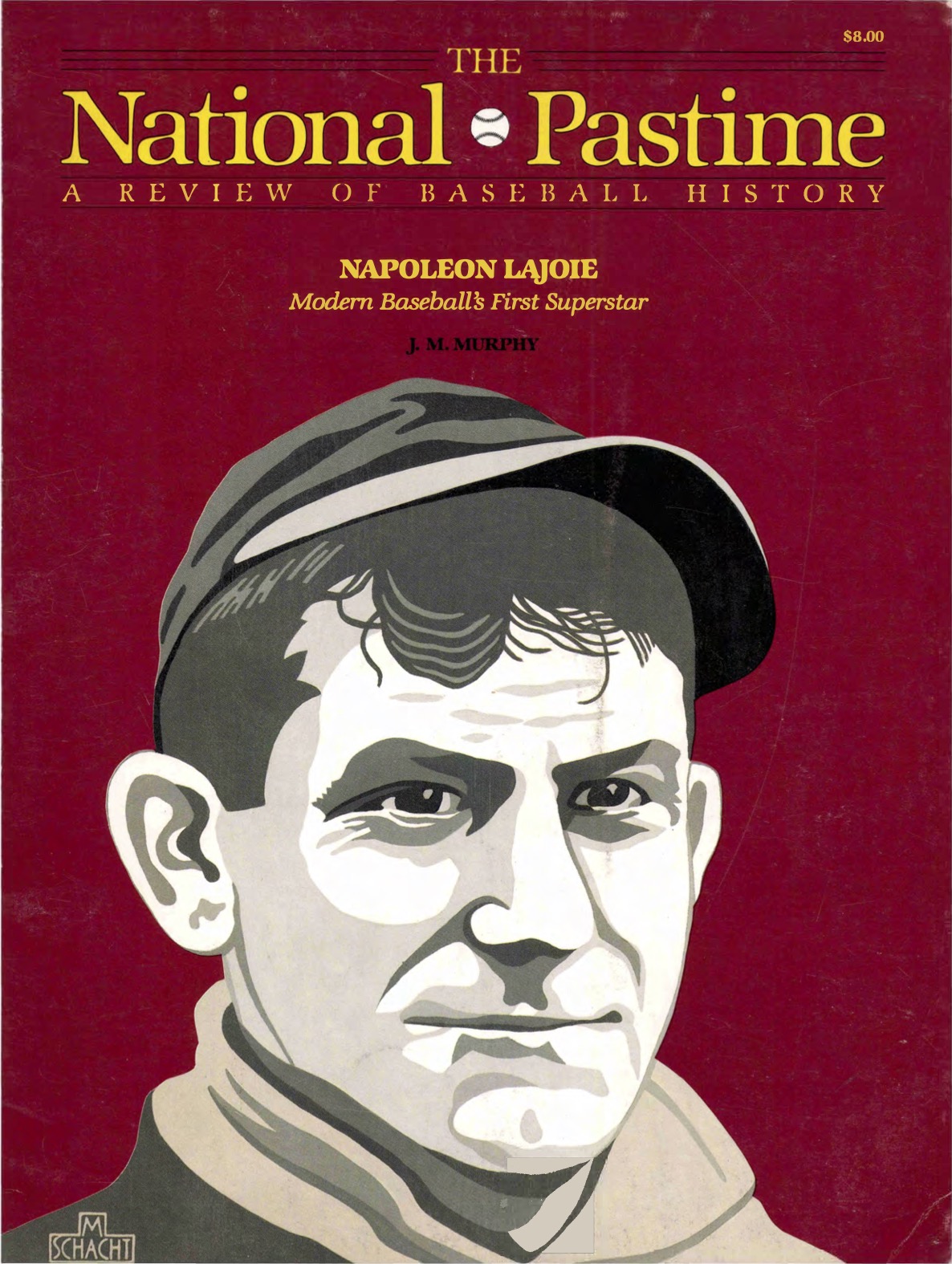

Napoleon Lajoie: Baseball’s First Modern Superstar

This article was written by James Murphy

This article was published in The National Pastime, Spring 1988

Editor’s note: James Murphy’s book-length biography of Napoleon Lajoie was published as the Spring 1988 issue of The National Pastime. Click here to download the PDF edition to view this special edition in its original formatting.

While the grounds crew is still scraping the infield and the starting pitchers are throwing in the bullpens, I want a brief chat with you about a few aspects of the Lajoie story.

Some of you may challenge the subtitle: “Modern Baseball’s First Superstar.”

Feel free. You can make a good case for Honus Wagner. I still vote for Nap.

You may challenge the word “Modern.” Feel free. Baseball’s modern era is often dated from 1900, the year before the American League made baseball a two-lane highway. I’ve chosen 1893, when the 6-by-4 “box” was moved back to 60 1/2 feet and the game took on its current look. That’s four years before Napoleon Lajoie played his first full season in the majors.

Researching can be difficult and frustrating, particularly when the subject and those who knew him best are long gone. Lives of great people usually become, at least in part, mythologized. Larry Lajoie is no exception. The printed word carries no guarantee of truth or accuracy, and in trying to pull together the life story of a man born over a century ago,the printed word has to be the prime source of material. With all due respect to William Cullen Bryant, Truth, crushed to Earth, will not necessarily rise again and know the eternal years; and Error,writhing in pain,will not necessarily die among its worshippers. Error will, all too often, be copied and copied again until it — not Truth — achieves eternity.

For example, I routinely checked with the Woonsocket city clerk’s office for Napoleon Lajoie’s date of birth. When they gave the date, I politely told them they must be wrong. They rechecked, with the same result. I wasn’t satisfied and obtained an official copy of his baptismal certificate. This confirmed that the date always given for Lajoie’s birth is incorrect. Apparently, in some printed record of long ago,the year of birth was erroneously indited — and the error has been repeated ever since.

In my research, I came across several interesting stories that I couldn’t confirm. Did Lajoie, for instance, insist on $100 a month, instead of the offered $75, before he’d sign his first pro contract? Was that contract signed on the back of an old envelope, used when the club owner forgot to bring a formal contract? Was that envelope a longtime keepsake with Lajoie? Did he dabble in real estate in his early retirement years? Was the quote accurate that had him saying his six-bunt day in St.Louis was “the greatest mistake of my life”?

I either don’t mention these unconfirmed accounts in the text, or I make it clear that they may not be accurate. For instance,when Lajoie was sold by Fall River to the Philadelphia Nationals, was he a “throw-in”? Nap himself was quoted years later that he was. I seriously question that, and in a section clearly labelled conjecture, I explain why and offer a scenario that seems logical and defensible.

Some erroneous printed material, of course, is easy to disprove. One interview I came upon had Lajoie saying his father was angry and disgusted “when I signed my first professional contract.” He signed with the Fall River team of the New England League in 1896. His father had died in 1881.

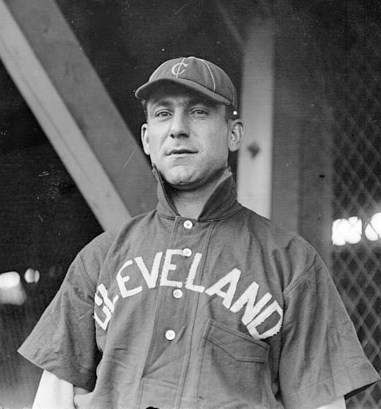

I toyed with the idea of subtitling this effort “The Forgotten Superstar,” partly because so little seemed to be known about him among baseball fans in general, and even among residents of his hometown of Woonsocket. So far as I could determine, no birth-to-death account of Napoleon Lajoie’s life had ever been attempted. Still, he was the sixth player ever elected to the Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, so “Forgotten ” isn’t quite apropos.

In any event, it’s important to remember that Napoleon Lajoie was one of the pioneers who played the game before it had insinuated itself into the fibre of America. In his early days,baseball was accorded limited space in the general press: When Lajoie quit as manager of the Cleveland Naps in 1909, one Rhode Island paper headlined the story in type about as big as these words you’re reading. As baseball grew in stature, it became the most annotated of sports, thanks to the groundwork laid by the Ansons, Burketts, Kellys, Youngs, Delehantys — and Lajoies.

Well, the managers have exchanged lineups, and the umps, in solemn conclave have explained the ground rules (they haven’t changed in half a century) … and there’s the home pitcher strolling to the mound — so “Play Ball!” Hope you enjoy.

JAMES M. MURPHY is a retired newspaperman. He first worked with the Worcester, Mass., Evening Post, then spent some 35 years with the Pawtucket, R.I., Times, serving in several capacities, including city editor and managing editor. A graduate of Holy Cross College, he is the author of The Gabby Hartnett Story — from a Milltown to Cooperstown. He resides in Pawtucket.

Click the cover image to download the PDF edition of the Spring 1988 The National Pastime (Volume 7, No. 1) to view this special biographical issue in its original formatting:

Link: https://sabr.box.com/shared/static/q5zzaqbhqnbwq254cj9xo6ojp5bk53ja.pdf