Negro League Baseball, Black Community, and The Socio-Economic Impact of Integration

This article was written by Japheth Knopp

This article was published in Spring 2016 Baseball Research Journal

This essay will explore the subject of racial and economic integration during the period of approximately 1945 through 1965 by studying the subject of Negro League baseball and the African American community of Kansas City, Missouri, as a vehicle for discussing the broader economic and social impact of desegregation. Of special import here is the economic effect desegregation had on medium and large-scale Black-owned businesses during the post-war period, with the Negro Leagues and their franchises serving as prime examples of Black-owned businesses that were expansive in size, profitable, publicly visible, and culturally relevant to the community. Specifically, what we are concerned with here is whether the manner in which desegregation occurred did in fact provide for increased economic and political freedoms for African Americans, and what social, fiscal, and communal assets may have been lost in the exchange.

The Kansas City Monarchs baseball club and the Kansas City African American community serve as a focal point for a number of reasons, including access to sources, the stature of the Monarchs as a preeminent team, the position of Jackie Robinson as the first openly Black player to cross the color barrier in the modern period, and the vibrancy of the Kansas City Black community. Also, Kansas City is unique in that it was the westernmost major metropolis in a border state, straddling the line between North and South and taking on aspects of both.1 However, in most respects the setting for this essay could have been any urban Black area in the United States in this period, with Kansas City being quite representative of the time. St. Louis or Chicago, Newark or Pittsburgh, across the country a general theme emerges of increased political and economic freedoms for African Americans, at least within segregated communities that in many ways were lost after increased contact and competition with White-owned businesses.2 All of these communities would in this period struggle with the ramifications of “White Flight,” decapitalization of urban areas, prejudicial hiring and housing policies, and increased economic competition.3 The story of Black enterprise in America follows a close parallel to what happened to the Negro Leagues.

AUGUST 28, 1945; 18TH & VINE, KANSAS CITY, MO

The headlines of the Kansas City Call, the local Black newspaper, were still filled with post-war optimism but also with trepidation over continuing economic and civic issues in the months following the end of the war. From the Friday, August 31, 1945, edition we find that the S & D Process Company, an all-Black mail order distribution house, had been abruptly closed, laying off its last 60 workers, most of whom were women. At the height of the war the firm had employed some 245 Black workers.4 In the same issue it was announced that the local office of the Federal Employment Practices Commission (which sought to provide more fair hiring and employment standards for minorities, especially in heavy industry and manufacturing) had been closed and was being incorporated in the St. Louis office.5 The writer had some concerns for what this meant for the Black workers in the area.

Perhaps the most troubling news item from this issue was the case of Seaman First Class Junius Bobb, a Black sailor arrested for allegedly starting an altercation with a White Marine at Union Station rail depot. At press time the Navy would not disclose details, saying only that the incident was under investigation and that Seaman Bobb would stand trial for assault at Great Lakes Naval Training Center outside of Chicago. According to eyewitnesses, the Marine began the exchange by verbally and physically assaulting Seaman Bobb. The Shore Patrol arrived shortly thereafter and several military policemen began to beat Seaman Bobb with batons in full view of the public. The Marine in question was not arrested. Seaman Bobb’s condition was unknown and he was being held incommunicado. The NAACP had announced that they would be providing legal counsel if Seaman Bobb did not prefer a Navy lawyer.6

On the whole, however, the general tone of the paper was upbeat and optimistic. While issues involving economic and legal inequality dominated the front page, there were many more stories celebrating success stories from the Black community. Local girl Yolanda Meek had been awarded a $5,000 scholarship by the Delta Sigma Theta Sorority.7 Op-ed columnist Lucia Mallory wrote about the importance of continuing to support the government by buying bonds even after the war had ended, and appealed to her readers to donate clothes and other supplies to the relief effort for victims of war-torn Europe.8 Even though the local office was being closed, the FEPC was scheduled to hold a meeting October 14 at Municipal Auditorium called “An Industrial Job for all who Qualify,” focusing on retaining Black employment in the industrial sector after shifting to a peace-time economy.9

Many of the same sentiments were echoed in another local Black newsletter, which on the front page expressed concern about the unemployment rate of the African American community and what postwar demobilization would mean for the Black worker. While employment rates among Black workers had doubled between 1940 and 1943, there had already been numerous layoffs in the various wartime industries, where Black workers faced a “last hired, first fired” mentality.10 Companies such as Remington Arms, North American Aircraft, Aluminum Company of America, and Pratt and Whitney Aircraft had increased their employment of Black workers by some 200% during the war, 30% of whom were women.11 What would become of these jobs in peacetime was a major concern. However, the inside fold of the circular contained stories of decorated Black service members from the area, making special note of how many of them had been commissioned officers. These consistent themes of concern over civil liberties and economic opportunities intermixed with a sense of community pride and optimism seem to have been pervasive at this time.

This same general pathos is reflected in The Call’s sports pages. No fewer than four articles were dedicated to the Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro National League and one of the most storied Black teams in baseball history. After dutifully reporting game summaries giving details of two lost games in a doubleheader to the Chicago American Giants by scores of 15–1 and 2–1, the writer moved on to more pleasant aspects of the club. There was a small writeup about the antics of legendary pitcher and showman Satchel Paige, who was equally famous both for his abilities as a player and for his on-field theatrics that dazzled the crowd and added to his already mythic persona. Another item advertised for the upcoming Labor Day doubleheader against the Memphis Red Sox in which ace pitcher and future Hall of Famer Hilton Smith was scheduled to pitch.12 Somewhat surprisingly, there was no mention of star rookie shortstop Jackie Robinson, who was having one of the finest seasons of any player in the league.13 While the official announcement would not be made until October, this was the first issue of the Monarchs’ local paper following the historic signing of Robinson by Branch Rickey and the Brooklyn Dodgers on August 25, becoming the first Black player in the twentieth century to have signed with a major league team.14

In the immediate wake of World War II, economic prosperity was permeating all levels of society (though admittedly distributed unequally) and Kansas City’s African American community was no exception. Having weathered the Great Depression with unemployment and business failure rates much higher than their White counterparts, businesses were booming in the early postwar period. More than half of all businesses in Kansas City’s Black section were owned and operated by African American proprietors. While most of these were small-scale service sector operations, there were also banks, insurance agencies, doctors’ offices, and law firms. More than 200 local Black-owned businesses provided hundreds of jobs and an average weekly salary of $23.81, which was still below the national median, but much improved from just a few years prior.15 Returning veterans were taking advantage of the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944 and other benefits to open new businesses and purchase their own homes.16 Employment opportunities for African American women had improved in this area to such an extent that there was a shortage of domestic workers available to work for wealthy White households.17

Increased economic opportunities and a sense of empowerment from wartime achievements (combined to a smaller degree with new government programs) fostered a zeitgeist of activism more commonly ascribed to the Civil Rights Movement of a decade later. Instead of maintaining the status quo, there were numerous new groups organized to push for expanded rights in the fields of healthcare, housing, employment, and access to advanced education and other public amenities. Organizations such as the Urban League were becoming increasingly vocal and insistent upon equal opportunity as well as instilling a sense of civic pride in the accomplishments of local African Americans.18

The epicenter of the African American community was located around 18th Street between Vine and The Paseo. Businesses of all types, from barber and shoe repair shops to doctors’ and lawyers’ offices were found in this neighborhood. This section of town was perhaps best known for its night life, with patrons packing clubs with colorful names such as the Cherry Blossom, the Chez Paree, Lucille’s Paradise, and the Ol’ Kentuck’ Bar-B-Q.19 Kansas City was a regular tour stop for many of the biggest names in blues and jazz from this period. Count Basie and his orchestra, Cab Calloway, Billie Holliday, and Louis Armstrong, among many others, could frequently be found playing the many venues in this district.20

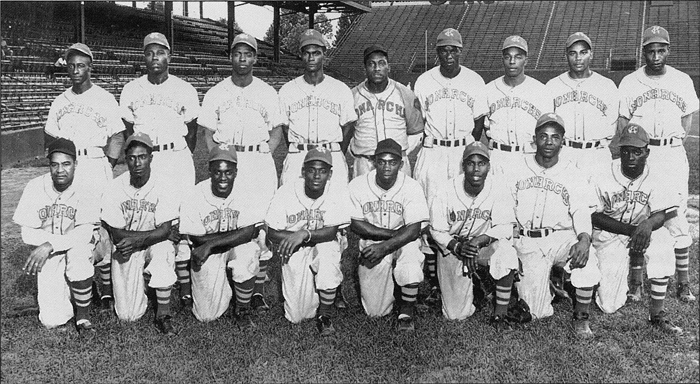

And of course, there were the Monarchs, arguably the greatest team of the Negro League era and perhaps one of the finest clubs in baseball history. With perennially winning teams built around future Hall of Famers like Satchel Paige, Cool Papa Bell, and Jackie Robinson, as well as Buck O’Neil, whose bronze image stands near the Cooperstown shrine’s entrance, the Monarchs were consistently one of the top drawing teams in baseball (Black or White) and nearly always in championship contention. Established shortly after the turn of the century as a barnstorming team, they had been a central element of the Black community for years before the establishment of the Negro National League in 1920, and would go on to dominate that circuit for several years before playing as an independent club for a number of seasons and then becoming a charter member of the Negro American League in 1937.21

Besides fielding a consistently competitive team, playing in one of the newest and nicest ballparks in the Negro Leagues also helped attract fans. Muehlebach Field, which opened in 1923 and would go through a number of name changes before settling on Municipal Stadium in 1955, was shared by the Monarchs and the Kansas City Blues, the top minor league club in the Yankees farm system. Located on Brooklyn Avenue a few blocks south of 18th Street, the stadium straddled the dividing line between the Black and White sections of town and attracted spectators from both. Being as the Monarchs were nearly always in contention for the pennant, Municipal Stadium would host several Negro League World Series, beginning with the first one in 1924. By the 1940s shifting demographics placed Municipal Stadium squarely in the African American area of town and would remain the home of the Monarchs for the rest of their tenure in Kansas City.22

The question becomes why, then, if social and economic conditions were improving exponentially in the African American community some ten years before what is nominally considered the beginning of the Civil Rights Era, were circumstances at the culmination of this period (and to an extent, today) practically unchanged, if not worse? The answer lies in how integration occurred, with White-owned businesses able to expand their market share at the expense of Black-owned businesses, while at the same time cherry-picking the best-educated and most-qualified Black workers and controlling the methods, timing, and public perception of desegregation.

ROLE OF BASEBALL AND BLACK BUSINESSES AS COMMUNITY TOUCHSTONE

One point that has been fairly well developed in the literature is the concept of baseball as community focus. While this model does not apply to African Americans exclusively, one of the most recurring points made in the various histories of the Negro Leagues in particular and Black baseball generally was how these teams served a communal purpose. Baseball functioned as a critical component in the separate economy catering to Black consumers in the urban centers of both the North and South. While most Black businesses struggled to survive from year to year, professional baseball teams and leagues operated for decades, representing a major achievement in Black enterprise and institution building.

Kansas City in this period was known not only for its ball club, but also as a hotbed of the jazz scene, and of course for its world famous barbeque. All of these elements merged in the Kansas City Black community, centered in the inner-city area of 18th and Vine. According to Monarchs manager and first baseman Buck O’Neil, this was an exciting time and place to be a part of.

[P]laying for the Monarchs in the late thirties and early forties, staying in the Streets Hotel at 18th and Paseo, and coming down to the dining room where Cab Calloway and Billie Holiday and Bojangles Robinson often ate. ‘Course, some of them were having supper while we were having breakfast and vice-versa. ‘Good morning, Count,’ I’d say. ‘Good evening, Buck,’ Mr. Basie would say. As somebody once put it, ‘People are afraid to go to sleep in Kansas City because they might miss something.’

Nowadays that downtown neighborhood is kind of sleepy, though we have some plans to wake up the ghosts. But we could never bring it back to its glory days.23

While Kansas City may have been somewhat unusual in the variety of activities available and the prominence of its Black celebrities, these themes can be found in urban Black communities throughout the North during this period. As desegregation gained momentum throughout the postwar era, many Black owned businesses were unable to effectively compete with White-owned firms who were now serving, and in some cases employing, African Americans. During the 1950s and 1960s, “White Flight” to the suburbs would continue to draw capital away from urban centers where Black communities tended to congregate, leading to large-scale vacancy, plummeting property values, and blighted areas where crime became more frequent. As O’Neil notes, there have been many plans for urban renewal to help reinvigorate these areas. In the case of the 18th and Vine district in Kansas City, these efforts have been largely successful; however, other cities have met with more limited success.

In Jack Etkin’s Innings Ago: Recollections by Kansas City Ballplayers of their Days in the Game, O’Neil discusses how Black teams provided a community focus for groups of African Americans living outside of cities with Negro League teams and in rural areas with small Black populations.24 According to O’Neil, when a team such as the Kansas City Monarchs barnstormed through small towns in the South and Midwest, often the entire Black population in the area would turn out, wearing their Sunday best. For these fans, the attraction was perhaps not so much the game itself, but rather the expression of African Americans being treated with something like equality (as in playing on equal terms against White teams) and often demonstrating their ability to compete successfully. For many, these exhibitions were a highlight of the yearly social calendar.25

Baseball was of course not the only type of business to serve as a communal focal point. Many businesses, most notably barber shops, beauty parlors, and, perhaps to a lesser extent, night clubs and restaurants also filled this role. The financial stability these businesses provided, in conjunction with a safe and separate space, led to business owners (and beauticians in particular) being leaders and activists in the Black community with these shops being at the center, like a base of operations for these activities.26 With increased competition from businesses outside the Black community coupled with decapitalization of inner-city areas, the importance of African American owned and operated businesses as a unique space for organization and communal fellowship began to erode.

ECONOMIC IMPACT OF BLACK BASEBALL

By the early 1920s, with a booming economy generally, and a fast growing and racially aware Black population in Northern and Midwestern urban centers, the stage was set for professional African American baseball leagues to successfully develop, and this was certainly the case in the Kansas City community. Between the 1920s and 1950s there would be ten professional Black leagues, though the most successful were the Negro National League (NNL) which operated between 1920 and 1931 and then from 1933 through 1948 and the Negro American League (NAL) from 1937 to 1960.27 It is hardly coincidental that successful organized Black baseball began in this period. Black populations in Northern cities boomed during the 1910s with the Great Migration from the South and relatively plentiful job opportunities in defense industries during World War I. This was also the period of Garveyism, the Harlem Renaissance, and the first wave of Black Nationalism. This combination of expendable income, leisure time, and racial awareness all helped to make Negro League baseball popular within the African American community and for the first time profitable for its proprietors. Throughout the 1920s Black teams continued to make money, and while paid substantially less than their White counterparts, African American players earned about twice the national median income.28

However, by the end of the decade Black baseball was in steep decline. The reason for this reversal of fortunes was primarily economic. While national unemployment rates during the Great Depression would peak at about 25% and White baseball saw substantial decreases in attendance, the jobless rate among African Americans was considerably higher.29 With deteriorating economic conditions, fans attended far fewer games, and teams and leagues began to fail. It was during this period that illegal money, particularly from gambling interests, began to be a major influence in the Negro Leagues. At least two teams were financed entirely by illegal gaming, though it is believed that several other teams may have also been involved.30

What the true intentions of the gamblers were remains a source of debate. While it is undoubtable that some teams, such as the Newark Eagles owned by Abe and Effa Manley and Gus Greenlee’s Pittsburgh Crawfords, served as fronts for laundering money, these owners also claimed to have had a genuine desire to keep their teams afloat and to continue to serve as a community focal point. There is some evidence to support these claims as these owners were well known within the Black community and were frequent donors to charities and social causes.31

Whatever the intent, it is unlikely that the Negro Leagues could have survived the Depression without this influx of capital. Also, the sources of capital and intentions of White owners of major and minor league teams were likely not always completely pure. Several teams were owned by beer barons, and there is much speculation that some of these teams were used as a means of washing monies.32 While Black owners were criticized (sometimes fairly) for being connected with illegal gaming and numbers-running, there were major league owners during the same period who actually owned casinos and horse tracks.33

This trend in Black baseball was mirrored in African American owned businesses more broadly. In 1932, there were 103,872 Black owned businesses in the United States. While most of these were small “mom and pop shops,” there had also been growth during the 1920s in larger-scale operations such as insurance companies, publishing houses, and banks. However, even with diversification of business types owned by African Americans, these businesses continued to depend almost exclusively on Black customers. With widespread unemployment during the Great Depression (made worse in the African American community due to prejudicial hiring practices), there was less disposable income for Black customers to spend. Predictably, Black-owned firms began to fail and by 1940 the number of Black-owned businesses had declined by 16% to 87,475.34

The situation in Kansas City was different and unique in the league, as the Monarchs had a White owner, J.L. Wilkinson, who had long sponsored integrated (both by race and sex) barnstorming teams based out of Kansas City. He became one of the charter owners of the Negro National League. While this was a source of conflict for some of the owners, including league founder Rube Foster, Wilkinson’s reputation for fairness (plus the fact that he held the lease on the one suitable ballpark) persuaded the owners to accept him into the fold.35

After narrowly surviving the 1930s, the Negro Leagues were in resurgence during the first half of the 1940s. Nearly full employment due to the war effort once again gave many African Americans disposable income. For the first time in more than a decade, teams consistently made money, and attendance was at an all-time high. Some teams were assessed as being as valuable as major-league franchises.36 As the postwar period of economic prosperity set in and all sectors of the population saw rising income levels and standards of living, indications were Black businesses, including the Negro Leagues, were finally about to fulfill their potential. This was not to be.

Somewhat paradoxically, for many Negro League teams the years between 1947 and 1950 would be their most financially successful, but this was due almost exclusively to selling the contract rights of their players to White-owned teams in both the major and minor leagues.37 Whereas the postwar period began very promising for the Negro Leagues with growing attendance, within just a few years most Black fans had taken to following their favorite players in the major leagues, and ticket sales fell off precipitously.

To complicate matters further, a number of White teams refused to honor the contracts of the Negro Leagues and pirated the players outright without compensating the team owners.38 At other times owners sold the rights to players at below-market prices, finding it better to get some return rather than risk having the player signed outright. By 1948 only the NAL was still in operation, and it was relegated to minor league status. In the early 1960s there were only a few teams left and the league disbanded, though some clubs—like the Monarchs—continued to barnstorm. The Indianapolis Clowns were the last Negro League team in business and played their final game in 1988.39

WHITE FLIGHT, DECAPITALIZATION, AND THE AFRICAN AMERICAN COMMUNITY

Another important element during this period concerns the decapitalization of urban areas (and especially parts of cities where African Americans tended to congregate) and migration of White families to suburban communities from the late 1940s through the early 1960s. Again, Kansas City serves as a model, with several large industries leaving the center-city area in the 1950s and relocating to suburban areas where most White workers continued to be employed while laying off most of the Black workforce. The change began in earnest in the early 1950s with the decline of the railroad industry, chiefly due to competition from automobile and air travel. Union Station, which had been the second busiest rail terminal in America after Chicago and employed large numbers of African Americans in various capacities, declined rapidly and fell into disrepair.

Another blow to the economy came with the Great Flood of 1951 which destroyed much of the stockyards located in the West Bottoms section. The stockyards, which were also second nationally to Chicago in size, never fully recovered as the cattle industry moved away from urban centers. With both of these industries went many comparatively well-paid and often unionized jobs.

As in baseball, in many middle- and large-scale industries, Black-owned firms were unable to compete with their White counterparts after racial integration. Many skilled Black workers were lured away to work at better-paying and more prestigious White-owned businesses. This clearly happened in baseball, where the very best Black and Latino players went to the major leagues, forcing the Negro Leagues to try to compete with less talented players.

This was again the case in Kansas City. In 1955 the Philadelphia Athletics moved into Municipal Stadium, where the Monarchs played, and though they were always near the bottom of the American League standings and moved on to Oakland after a number of seasons, this increased competition for entertainment dollars and use of public facilities forced the Monarchs out. In the mid-fifties the Monarchs were sold, and while they retained the name “Kansas City Monarchs,” this was a device used as a draw at the gate. The team was headquartered out of Flint, Michigan, until it finally folded in the mid-sixties, only occasionally playing in Kansas City.40

“White flight” also affected baseball as new stadiums for almost every major-league team during the 1960s and 1970s were nearly always located away from inner-city areas whereas previous stadiums had been almost exclusively located in downtown areas. This would happen in Kansas City, where the aging Municipal Stadium was abandoned and the Truman Sports Complex—with stadiums for both the new Kansas City Royals and Kansas City Chiefs of the National Football League (NFL)—was built near the interstate many miles away from the city’s downtown area and much closer to the then predominately White suburbs.

ECONOMIC COSTS OF DESEGREGATION ON NEGRO LEAGUE BASEBALL

While the integration of professional baseball is often seen as a benchmark in the history of civil rights, this did not come without great cost—financial and otherwise—to Black baseball and the African American community broadly. Again, this is in keeping with what happened in other large-scale Black-owned businesses such as banks, newspapers, and insurance companies.41 As events unfolded, the best Black players were cherry-picked by major-league clubs, leaving the Negro Leagues to try to compete for fan dollars with fewer quality players and less cultural significance.

Of the 73 players who would jump from the Negro Leagues to the majors, eight would be inducted into the Hall of Fame. Between 1947 and 1959, former Negro Leaguers would supply six Rookies of the Year and nine Most Valuable Player winners.42 Black baseball, like many other African American-owned businesses, now had to compete against White-owned businesses for Black clientele and with less talent, capital, and cultural privilege than their White counterparts. The result would be the collapse of the Negro Leagues (and many other Black-owned enterprises) which in conjunction with White Flight left many urban areas much less economically viable and with fewer opportunities for capitalization. From the middle 1950s through the 1970s most major-league teams left their inner-city ballparks for new stadiums closer to the predominately White suburbs, which further removed Black fans from the game.43

Making matters worse for the Black-owned teams was the practice of pirating Black players without compensating their former teams. Citing a lack of proper contracts (which is to say, contracts that had been approved for use in the White major and minor leagues), teams simply ignored the vested interests of Black clubs and signed the many of the best players outright without any financial consideration of Negro League owners.44 Denouncing Black-owned businesses as being illegitimate and therefore ethical to deal with in an inequitable manner had long been a common practice among White business owners. This view was both obviously exploitative and paternalistic, harkening to the 19th-century stereotypes of Black people being unsophisticated and childlike and their efforts being seen as cargo cult-like mimicry of Whites rather than legitimate expressions of capitalism.

It is also important to remember that the failure of the Negro Leagues economically impacted many more people than the players on the field. An entire support staff of front-office personnel, groundskeepers, concessionaires, ticket-takers, bus drivers, and so forth were all necessary to put a game on the field. These workers in turn then patronized local businesses. When the teams began to struggle and finally collapsed, many people besides the players also lost their livelihoods. Similarly, as African Americans lost market share of industrial and manufacturing jobs, the service sector also suffered as their regular clientele had increasingly less disposable income. Coupled with increased competition with White-owned businesses, many Black-owned urban enterprises began to go under.

ALTERNATIVE PATHS TO INTEGRATION

The manner in which integration in baseball—and in American businesses generally—occurred was not the only model which was possible. It was likely not even the best approach available, but rather served the needs of those in already privileged positions who were able to control not only the manner in which desegregation occurred, but the public perception of it as well in order to exploit the situation for financial gain. Indeed, the very word integration may not be the most applicable in this context because what actually transpired was not so much the fair and equitable combination of two subcultures into one equal and more homogenous group, but rather the reluctant allowance—under certain preconditions—for African Americans to be assimilated into White society.

Another negative aspect of the manner in which baseball was integrated was the unofficial, but common, practice of using racial quotas. Beginning with Rickey’s Dodgers, most major league teams—with a few notable exceptions such as Bill Veeck’s Cleveland Indians, who became a powerhouse behind several Black stars—kept roster spots for African American players to a minimum. Black players were nearly always signed in even numbers, so that their White teammates would not have to share rooms with them on the road.45 It was not at all unusual to see a Black player traded or sent to the minors if there were “too many” Black players on the squad.46 Additionally, while Black players often made more money than their White colleagues, this was mostly because almost every Black player of the 1940s and 1950s was a star. Slots for journeymen and utility players were the exclusive territory of White players. The message was clear; produce more than the average White player or leave.

After Jackie Robinson broke the color line, executives and owners from the Negro Leagues met with their counterparts from the major leagues and proposed a number of options for mergers and cooperation. At first it was suggested that the better clubs with large fan bases from the Negro Leagues, such as the Monarchs and Crawfords, be allowed in as expansion franchises.47 Several of these teams operated in cities without major league teams to compete with, already had large followings and the logistical infrastructure in place, and were perfectly positioned to help the major leagues take advantage of post-war prosperity and newly expendable income. The proposal was unanimously voted down. When this was rejected, the possibility of the Negro Leagues becoming a AAA circuit was raised. This too was summarily dismissed.48 White owners had no interest in cooperating with their Black counterparts, and instead of engaging in a business enterprise which would have most likely proved beneficial for all parties, the major leagues made a deliberate choice to put the Negro Leagues out of business after obtaining their best players and wooing away much of their fan base.

SEPTEMBER 1965; 18TH & VINE, KANSAS CITY

Twenty years later the tone was considerably more pessimistic. The headlines of The Call still carried stories about violence and inequality within the Black community but gone was the sense of optimism or increasing opportunity. The lead story from the September 1965 issue (at this point, The Call had become a monthly rather than weekly publication) led with a story titled, “Vicious Attack on Farmer: Admits Cutting Man’s Tongue Out,” in which a young Black man killed an elderly Black farmer while attempting to keep him from being able to testify against him regarding a crime the older man had witnessed by removing his tongue.49 Other headlines include, “Three Whites Arrested in Brewster Killing,” “Slain Priest Buried in Home Town,” “2,200 Still in Jail from L.A. Rioting,” and “NAACP Official Injured in Bombing.”50

The paper also ran a two-page summary of a study analyzing the underlying causes of racial violence. The story, titled “New Study Tells Why Riots Occur,” examined fifty years of data and concluded that riots occur when Whites feel economically threatened and local authorities, particularly the police, are not adequately trained to properly handle the situation.51 Clearly, racially related violence had by the middle 1960s become a pervasive issue, and other concerns seemed secondary. There are no mentions of scholarships being awarded, mass meetings for employment opportunities, or patriotic calls for donations and privation here.

The sports page is no less bleak. There is no mention of the hapless Kansas City Athletics who were stumbling to another disappointing finish. The only mention of baseball at all was an incident on August 22 when Juan Marichal of the San Francisco Giants beat L.A. Dodgers catcher Johnny Roseboro repeatedly in the head with a baseball bat, leading to a fine and suspension by the National League.52 Even in baseball, violence seemed to permeate. There was also no mention of the Monarchs, long a source of civic pride, who probably played their last game about this time.53

A return visit to what had been the heart of the Black community reiterates this theme. Whereas 20 years before, 18th Street was a vibrant center for art and commerce, it had by this time become little more than a ghost town with nearly all the buildings abandoned and left to deteriorate. The first blow came under the guise of reform, when a number of new “blue laws” made it increasingly difficult for the night clubs to operate profitably. Similarly to many other inner-city areas, urban renewal projects that were intended (at least in theory) to help revitalize the area had the exact opposite effect. In the middle 1950s five acres of historic buildings were razed in order to make room for new building projects. However, due to poor financing this area sat vacant for many years and became known as a dangerous place to walk through.

With new public accommodation laws came increased competition with other businesses outside of the traditional Black section of the city, and many African American owned shops—which generally had less access to capital, and prohibitive conditions attached when it could be found—were in most cases no longer able to operate profitably.54 By 1964, only two large buildings anchored the area, with the Kansas City Call still operating in the same space since 1922 on the east end, and the Lincoln Building housing several professional offices to the west. The corridor between the two comprised a few bars and a handful of shops, with nearly all of the storefronts boarded up in disuse and disrepair.55

Municipal Stadium would continue to be used on and off by various teams and for different events until the early 1970s, but little effort or funding was put into maintaining the structure. The primary reason given for moving the Athletics to Oakland was Kansas City’s lack of commitment to building a new ballpark.56 According to owner Charles O. Finley, the neighborhood had become too dangerous for night games, and he blamed the aging and inadequate facility for low attendance numbers (though one might argue that the club being at the bottom of the standings for more than a dozen years contributed more to low turnout). The promise of a new publicly financed stadium helped secure Kansas City an expansion team, the Royals, in 1969 and Municipal Stadium was finally abandoned after the 1972 baseball season.57 It sat unused and dilapidated until 1976 when it was demolished for being a danger to public safety.58 Professional baseball had left Kansas City’s African American community for the last time.

This seeming trend of negativism within the Black community at this time would seem paradoxical, at least in the traditional framework of American history. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 had been signed into law on August 6 of that year, and the Civil Rights Act of 1964, outlawing discrimination based on race, sex, or religion and segregation of public accommodations, was barely a year old. Why then, at a time of such apparent progress, does the record suggest such unfavorable conditions for many in the African American community? One would argue that despite the legal gains made during this period, which were substantial and should not be dismissed, the larger issue was access to economic opportunities. Indeed, the evidence reveals that levels of education and income in the early 1960s were essentially unchanged since World War II.59

These stagnant levels of earnings and upward are all the more telling being as this period witnessed some of the fastest and most widespread economic growth in American history. Increased competition, lack of capital, and the withdrawal of industry from inner-city areas all contributed to a rather bleak social and economic prognosis that no legislation could mitigate and which is still with us today.60

CONCLUSION

In many ways the story of Negro League baseball in general and the Kansas City Black community and ball club in particular provide an excellent example of the economic and social changes occurring in urban African American communities during the post-war era. While on the one hand the end (at least officially) of legal segregation and prejudicial hiring policies was clearly a victory for the cause of progress and many people have undoubtedly been able to succeed and have had opportunities that would not have otherwise been afforded them, it must be remembered that this came at a cost, and many of the long-term issues that have plagued inner-city areas are residual damage caused in large part by the manner in which integration occurred.

The reality is that much of the African American community was largely unaffected economically by the successes of the Civil Rights Era. Black workers lacking higher education and job skills, mostly due to an inadequate and unequal education system, remained trapped in low-paying jobs and neighborhoods with increasingly few amenities.61 While there was growth in this period among the Black middle class, these new jobs were almost exclusively in White-owned firms. Large-scale Black-owned businesses, unable to find new clients, sources of revenue, and at a competitive disadvantage for the patronage of their traditional customers, failed.

This is not to imply that segregation, economic or otherwise, was in any way beneficial to the African American community. The current face of American society would have been almost unimaginable at the beginning of the Civil Rights Movement. The fact remains, however, that in spite of discrimination and disadvantage, many Black entrepreneurs were able to find a niche market and achieve financial success. In the end desegregation happened on what were essentially the terms of the White majority, which in many ways benefited economically from the new arrangement, rather than honest assimilation combining the best qualities of both communities and building a more just and equal society.

JAPHETH KNOPP received a B.S. degree in Religious Studies and M.A. in American History from Missouri State University and is currently enrolled in the History Ph.D. program at the University of Missouri. He lives with his wife, Rebecca Wilkinson, and their son Ryphath. He can be contacted at Japheth.knopp@gmail.com.

Notes

1 Urban League of Kansas City. “The ‘Northern City with a Southern Exposure,’” Matter of Fact: Newsletter of the Urban League of Kansas City, Missouri. Vol. I; No. 1, July, 1945, 1.

2 Robert H. Kinzer and Edward Sagrin, The Negro in American Business: The Conflict Between Separatism and Integration (New York: Greenburg, 1950), 100–1.

3 Thomas J. Sugrue, Sweet Land of Liberty: The Forgotten Struggle for Civil Rights in the North (New York: Random House, 2008), 177–79.

4 “All-Black Company Closes Suddenly,” Kansas City Call. Vol. 27; No. 16, August 31, 1945, 1.

5 “Kansas City FEPC Office Closed,” Kansas City Call. Vol. 27; No. 16, August 31, 1945, 1.

6 I subsequently did some research on the matter, but was unable to discover the outcome of the trial or what became of Seaman First Class Bobb.

7 “Local Girl Awarded Scholarship,” Kansas City Call. Vol. 27; No. 16, August 31, 1945, 3.

8 Lucia Mallory, “Keep Buying War Bonds!” Kansas City Call. Vol. 27; No. 16, August 31, 1945, 4.

9 “FEPC to Hold Meeting,” The Kansas City Call. Vol. 27; No. 16, August 31, 1945, 5.

10 Urban League of Kansas City. Matter of Fact: Newsletter of the Urban League of Kansas City, Missouri. July, 1945, 1.

11 Census Bureau. 1950 United States Census of Population Report; Kansas City, Missouri (U.S. Govt. Printing Office; Washington, 1952), 17–19.

12 “Smith to Start Labor Day Double-Header,” Kansas City Call. Vol. 27; No. 16, August 31, 1945, 9.

13 Statistics for Negro League players are notoriously difficult to find exact figures for. Baseball-Reference.com, usually considered to be authoritative, lists Robinson as having a .414 batting average in 63 games that season, though this is probably incomplete.

14 Frank Foster, The Forgotten League: A History of the Negro League Baseball (BookCaps; No city given, 2012), 55.

15 Urban League of Kansas City. “Local Survey Made,” Matter of Fact: Newsletter of the Urban League of Kansas City, Missouri. Vol. I; No. 6, April–May, 1946, 2

16 Urban League of Kansas City. “Clinic for Small Business Draws Much Interest,” Matter of Fact: Newsletter of the Urban League of Kansas City, Missouri. Vol. I; No. 6, April 1946, 2–3.

17 Urban League of Kansas City. “’You Just Can’t Find Good Help Anymore,’” Matter of Fact: Newsletter of the Urban League of Kansas City, Missouri. Vol. II; No. 1, August, 1946, 2.

18 Urban League of Kansas City. “It’s a Matter-of-Fact that:” Matter of Fact: Newsletter of the Urban League of Kansas City, Missouri. Vol. 1; No. 1, July, 1945, 2.

19 Chuck Haddix, “18th & Vine: Street of Dreams,” in Artlog. Missouri Arts Council. Vol. XIII; No. 1, January –February, 1992, 3.

20 Ibid, 4

21 Janet Bruce, The Kansas City Monarchs: Champions of Black Baseball (University of Kansas Press; Lawrence, 1985), 117.

22 Ibid, 126

23 Buck O’Neil, I Was Right on Time: My Journey from the Negro Leagues to the Majors (Simon & Schuster; New York, 1996), 75–76

- 24. Jack Etkin, Innings Ago: Recollections by Kansas City Ballplayers of their Days in the Game (Walsworth Publishing; Marceline, MO, 1987), 18.

25 Ibid, 19.

26 Tiffany Gill, Beauty Shop Politics: African American Women’s Activism in the Beauty Industry (University of Illinois Press; Chicago, 2010), 2.

27 Leslie Heaphy, The Negro Leagues, 1869–1960 (McFarland & Co; Jefferson, North Carolina, 2003), 224.

28 Rob Ruck, Raceball: How the Major Leagues Colonized the Black and Latin Game (Beacon Press, Boston, Massachusetts, 2011), 101.

29 William Sundstrom, “Last Hired, First Fired? Unemployment and Urban Black Workers during the Great Depression” in The Journal of Economic History (Vol. 52, No. 2, June, 1992), 485.

30 Bob Luke, The Most Famous Woman in Baseball: Effa Manley and the Negro Leagues (Potomac Books; Dulles, Virginia, 2011), 11.

31 Ibid, 45.

32 Peter Golenbock, The Spirit of St. Louis: A History of the St. Louis Cardinals and Browns (HarperCollins; New York, 2000), 352.

33 Bill Veeck, Veeck–As in Wreck (University of Chicago Press; Chicago, 1962), 246-247.

34 Michael Woodward, Black Entrepreneurs in America: Stories of Struggle and Success (Rutgers University Press; New Brunswick, NJ, 1997), 18.

35 O’Neil, 77–78.

36 Ruck, 78.

37 Bruce, 118–19.

38 Veeck, 176.

39 Heaphy, 227.

40 Bruce, 126.

41 Robert E Weems Jr., Black Business in the Black Metropolis: The Chicago Mutual Assurance Company, 1925–1985. (Indiana University Press; Indianapolis, 1996), xv.

42 Ruck, 104–105

43 Lanctot, 395–96.

44 Mitchell Nathanson, A People’s History of Baseball (University of Illinois Press; Urbana, IL, 2012), 86–87.

45 Nathanson, 99.

46 Ibid, 103–104.

47 Ruck, 115

48 Ibid, 116

49 “Vicious Attack on Farmer: Admits Cutting Man’s Tongue Out,” The Kansas City Call, Vol. 46; No. 22, September 3, 1965, 1.

50 “NAACP Official Injured in Bombing,” The Kansas City Call, Vol. 46; No. 22, September 3, 1965, 1.

51 “New Study Tells Why Riots Occur,” The Kansas City Call, Vol. 46; No. 22, September 3, 1965, 1.

52 Bill James, New Historical Baseball Abstract (Simon & Schuster; New York, 2001), 253.

53 The exact date has proven impossible to track down after extensive research. By this point the team had been playing out of Flint, Michigan for several seasons, only keeping the name as a source of revenue. It is known that the team played most of the 1965 season and folded near the end of the year. September is a reasonable guess. It is also worth noting that the final game of one of the most storied franchises in the history of baseball may well be lost to us now. Just another example of how quickly and precipitously Black baseball fell out of the public eye.

54 Woodward, 26

55 Haddix, 5.

56 Herbert Michelson, Charlie O: Charles Oscar Finley vs. the Baseball Establishment (Bobbs-Merrill; New York, 1975), 125, 127–28.

57 Mark Stallard, Legacy of Blue: 45 Years of Kansas City Royals History & Trivia (Kaw Valley Books; Overland Park, KS, 2013), 6.

58 Lawrence Ritter, Lost Ballparks: A Celebration of Baseball’s Legendary Fields (Penguin; New York, 1994), 136.

59 United States Department of Labor. Home, Education, and Unemployment in Neighborhoods; Kansas City, Missouri, January 1963.

60 Andrew Brimmer, “Small Business and Economic Development in the Negro Community,” in Black Americans and White Business, Edwin Epstein and David Hampton, ed., (Dickinson Publishing, Encino, CA., 1971).

61 Woodward, 30–31.