Neill “Wild Horse” Sheridan and the Longest Home Run Ever Measured

This article was written by Rick Cabral

This article was published in Fall 2011 Baseball Research Journal

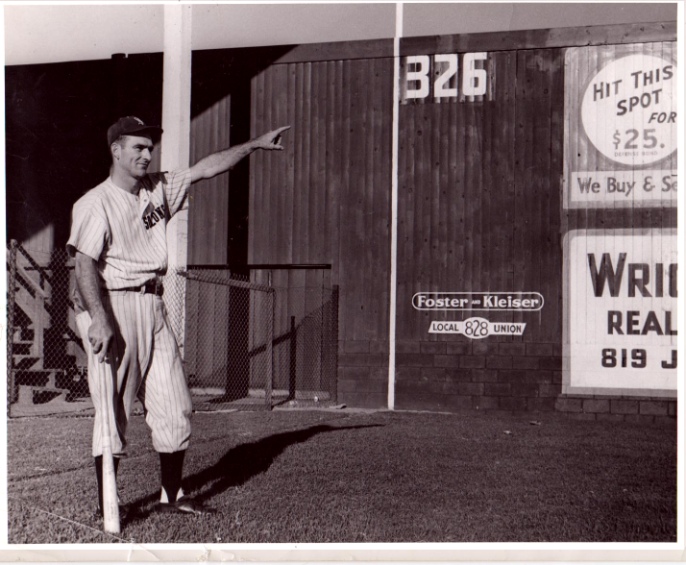

On a warm summer evening July 8, 1953, Sacramento Solon Neill Sheridan did something no professional ballplayer before or since has ever done. Between games of a twi-night doubleheader against the San Francisco Seals, he raced an Arabian horse—and won. Then in the nightcap, the right-handed slugger homered over the right-field fence, something no one had done all season at Edmonds Field.

And then came his fantastic feat.

Toward the end of the second game, Sheridan whacked a fastball, thrown right down Broadway by the Seals’ Ted Shandor, over the left center-field fence at Edmonds Field. Solon ballboy Gary McDowell, sitting in the dugout, remembers it started as a frozen rope that might have been snagged if the shortstop had been a foot taller. He said when it flew over the 356-foot mark of the barricade it continued up on an incline, heading toward the Sierra Nevada Mountains.[fn]Gary McDowell, telephone interview, 2 April 2010.[/fn] Solon third baseman, Eddie Bockman, who also watched it that night, concurred, saying, “I never saw one still going up as it left the ballpark, until that point.”[fn]Eddie Bockman, telephone interview, 2 April 2010.[/fn]

Toward the end of the second game, Sheridan whacked a fastball, thrown right down Broadway by the Seals’ Ted Shandor, over the left center-field fence at Edmonds Field. Solon ballboy Gary McDowell, sitting in the dugout, remembers it started as a frozen rope that might have been snagged if the shortstop had been a foot taller. He said when it flew over the 356-foot mark of the barricade it continued up on an incline, heading toward the Sierra Nevada Mountains.[fn]Gary McDowell, telephone interview, 2 April 2010.[/fn] Solon third baseman, Eddie Bockman, who also watched it that night, concurred, saying, “I never saw one still going up as it left the ballpark, until that point.”[fn]Eddie Bockman, telephone interview, 2 April 2010.[/fn]

Everyone in the ballpark who witnessed the blast knew it was one for the ages. But not until the next day did they appreciate the distance.

Entering his eleventh season of pro baseball, Sheridan had played for six teams, while amassing decent power numbers in the minors (94 home runs and 516 RBIs). In fact, he started the 1953 season with the Oakland Oaks but played only two games before moving to the Solons. Up to that point, the most home runs he had ever hit in one season was 17, so the name “Sheridan” didn’t exactly inspire thoughts of Ruthian clouts.

On July 9 the local newspapers—Sacramento Union and Sacramento Bee—didn’t even allude to the distance of Sheridan’s second home run the night before in their game reporting. Bee reporter Tom Kane focused more on the first smash when he wrote the following: “Sheridan’s first homer in the fourth inning of the second game was a 340 foot drive over the right-field wall. This is one of the few times a right-handed hitter has accomplished such a feat. His ninth of the season was into straight left field and knotted the count in the nightcap…”[fn]Tom Kane, “Sheridan Homers Twice As Solons, Seals Split Pair,” Sacramento Bee, 9 July 1953, 22.[/fn] [Italics mine.] Kane later mentioned that Sheridan’s ninth round-tripper—his second of the night—put him in the team lead for home runs. But no mention about the prodigious homer for which Sheridan would soon be known.

The Union’s story added that “Nobody last night could recall when a player had homered over both fences in the same game. As a matter of fact, the right-handed hitters who have reached the right wall can be counted without taking off the shoes.”[fn]Sacramento Union, 9 July 1953, 6.[/fn]

In fact, both papers’ sidebars gave more ink to the horse race between games of the doubleheader, with the Union’s photograph that morning showing Sheridan posed in a track runner’s starting position next to Rabric, the Arabian horse. The photo caption credits Sheridan with running the zig-zag course faster, with a time of 11.4 seconds versus the pinto’s 11.5.[fn]Ibid.[/fn] Ironically, Solon teammate Lenny Attyd originally was scheduled to run in the between-games stunt, but backed out at the last minute due to a cold. A volunteer was called for and Sheridan stepped forward to race the Arabian steed. (Technically, Sheridan didn’t race the horse. He ran a 60-yard zig-zag course with stakes 20 feet apart in the time of 11.4. The Arabian horse Rabric, ridden by Manuel Borges of Vallejo, California, ran the same course in 11.5. According to Western Horseman magazine, December 1954, the half-Arab pinto was named Rab-Ric.)

The day after the doubleheader, the Solons first learned of the possibility of Sheridan’s long home run when an unassuming-looking man approached Sheridan in the clubhouse with a baseball.[fn]Neill Sheridan, telephone interview, 2 April 2010.[/fn] At first, Sheridan thought he wanted an autograph. Instead, the man—Pat Kelly—told him after last night’s game he found the rear window of his automobile had been demolished and inside on the rear bench seat was a baseball. When Kelly spied the baseball and a seat full of shattered glass, he presumed it to be the work of the titanic Sheridan shot.

The day after the doubleheader, the Solons first learned of the possibility of Sheridan’s long home run when an unassuming-looking man approached Sheridan in the clubhouse with a baseball.[fn]Neill Sheridan, telephone interview, 2 April 2010.[/fn] At first, Sheridan thought he wanted an autograph. Instead, the man—Pat Kelly—told him after last night’s game he found the rear window of his automobile had been demolished and inside on the rear bench seat was a baseball. When Kelly spied the baseball and a seat full of shattered glass, he presumed it to be the work of the titanic Sheridan shot.

When asked where his car was parked, Kelly told them on Burnett Way, which was beyond the left-field wall and the Solons parking lot. Sheridan and his teammates were stunned. If the car had been parked there, the ball must have traveled an extremely long distance. In appreciation for returning the Homeric prize, Sheridan signed another Pacific Coast League ball and gave it to Kelly. Sheridan retains the home run trophy ball in his collection.

When team officials got wind of the rumor, Dave Kelley (no relation), the team’s publicist, had Kelly show him the spot where the car had been parked and he then stepped off the distance. The publicist charged into the Solons’ offices and reported to team president Eddie Mulligan that he’d come up with 600-plus feet. Mulligan ordered groundskeeper Horace Smith to get his tape measure and together the trio met on the other side of the left-field wall at the spot where they gauged the ball left the park. From there they marched across the parking lot on a diagonal line until they came to the place where Kelly’s car had been parked on Burnett Way. They came up with an additional 294 feet beyond the outfield fence. Which meant the ball traveled an approximate distance of 620 feet.[fn]Bill Conlin, “The Shot Heard Around The World,” Sacramento Union, 12 July 1953, 19.[/fn]

It’s clear that the ebullient team officials then reported their findings to the local beat writers, because on Friday, July 10, both papers picked up on the distance of Sheridan’s blast, reporting it was the longest home run ever measured, surpassing Babe Ruth’s 600-foot clout struck in a spring training game in Tampa, Florida, April 4, 1919.[fn]Staff reporter, “Sheridan Homer May Be Longest On Record,” Sacramento Bee, 10 July 1953, 26.[/fn] The writers also dutifully noted that it traveled much farther than the 565-foot home run clubbed by Mickey Mantle out of Washington’s Griffith Stadium in April. In Bill Conlin’s “It Says Here” column, the Union sports editor introduced the claimant as “Pat Kelly, a spectator residing at 2928 Broadway, said the ball landed in the back seat of his car while parked on Burnett Way.”[fn]Bill Conlin, “Was Sheridan’s Homer Longest of All-Time,” Sacramento Union, 10 July 1953, 8.[/fn] Conlin also reported that Mulligan “intends to have Sheridan’s drive officially measured.”

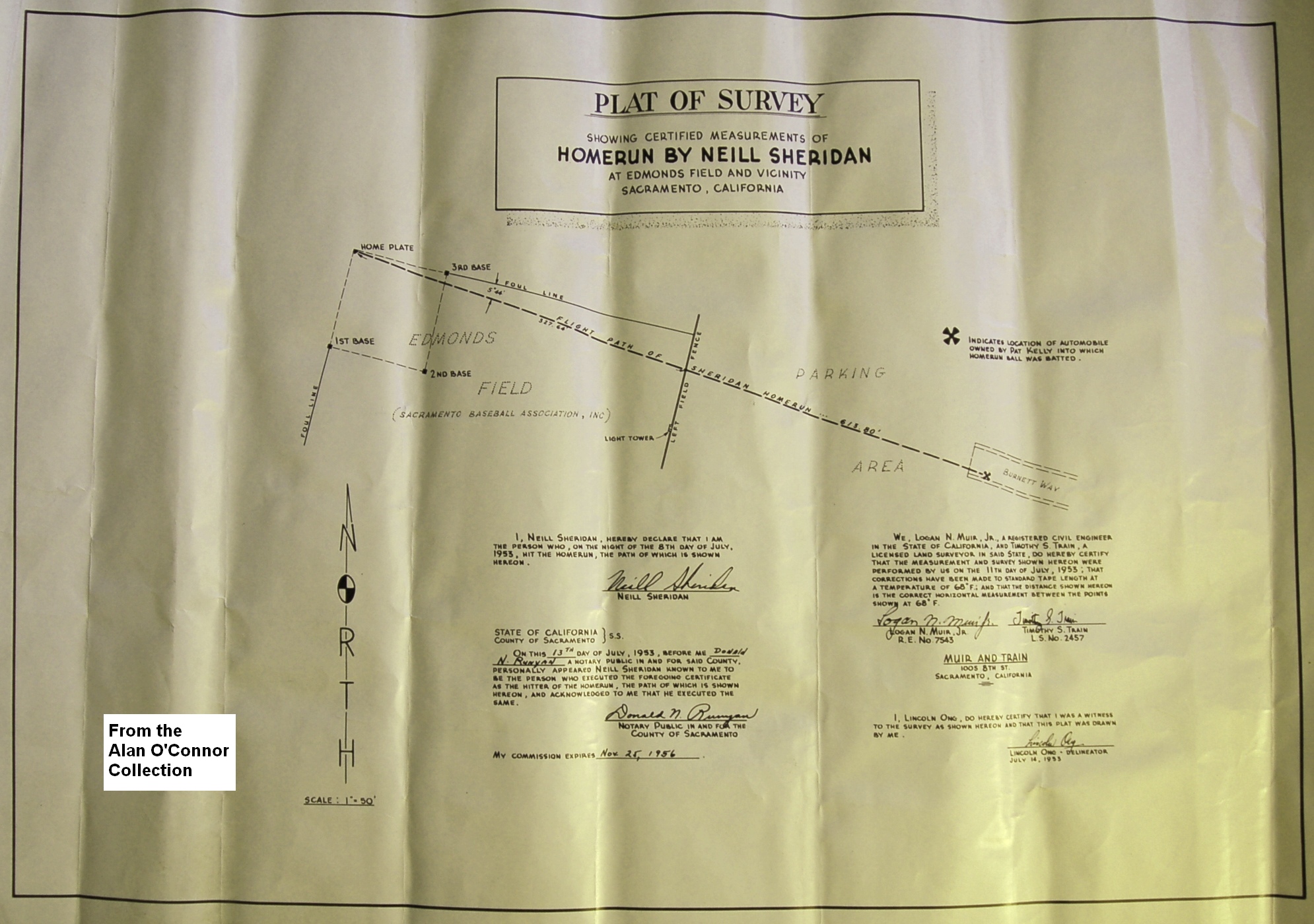

Apparently, Mulligan didn’t waste any time. The next morning, Saturday, July 11, a surveying team from Muir & Train set out to officially measure the distance. In a telephone interview, Timothy S. Train, a principal of Muir & Train company, recalled the surveying adventure, conceding it was a publicity stunt. “Our firm had just formed in March 1953 and we were hungry for new business.”[fn]Timothy S. Train, telephone interview, 9 April 2010.[/fn] He believes that his partner Logan N. Muir Jr. had contacted the Solons and offered the firm’s services at no charge.

Train and Muir together measured the distance using a standard surveyor’s steel tape with another member of their firm there to certify their findings. (Muir was the firm’s civil engineer and Train the land surveyor.) When the assignment was finished, they arrived at a slightly shorter, though more precise measurement of 613.8 feet. The Solons immediately revved their publicity machine.

In his July 12 column, Conlin noted that the Associated Press had broadcast the story across the globe. The Sporting News picked it up and reported it later that month.[fn]Staff reporter, “Solons Bosses Claim 614-Ft. Home Run for Neill Sheridan,” The Sporting News, 22 July 1953, 23.[/fn] Conlin wrote, “Certainly Sheridan, by out-Ruthing the Babe, and dis-mantling Mickey, contributed the most spectacular incident in the long history of Sacramento baseball.”[fn]Bill Conlin, “The Shot Heard Around The World,” Sacramento Union, 12 July 1953, 19.[/fn]

In his July 12 column, Conlin noted that the Associated Press had broadcast the story across the globe. The Sporting News picked it up and reported it later that month.[fn]Staff reporter, “Solons Bosses Claim 614-Ft. Home Run for Neill Sheridan,” The Sporting News, 22 July 1953, 23.[/fn] Conlin wrote, “Certainly Sheridan, by out-Ruthing the Babe, and dis-mantling Mickey, contributed the most spectacular incident in the long history of Sacramento baseball.”[fn]Bill Conlin, “The Shot Heard Around The World,” Sacramento Union, 12 July 1953, 19.[/fn]

Then, in an attempt to counter the critics, the sage scribe jotted a series of justifications for Sheridan’s sudden power surge. First off, Conlin noted that Sheridan had distinguished his power that night by hitting two home runs for the ages as cited above.

Conlin introduced the possibility that the ball may have bounced in the Solon’s parking lot (beyond the left-field wall) and then smashed Kelly’s rear window. Solons’ President Mulligan countered that argument by saying, “It was a car with a sloping rear window. In order to break the glass and land in the car, the ball would have had to be dropping from above instead of bounding off the ground.” Two former Solons employees (Ron King, a ballboy from 1936 to 1946 and Cuno Barragan, a Solons player in the mid-1950s) confirmed for this writer that the parking lot was unpaved and probably covered with gravel at the time.[fn]Ron King, personal interview, 6 April 2010. Cuno Barragan, personal interview, 15 November 2010.[/fn] If true, it appears unlikely a ball could bounce in the parking lot with enough force to penetrate Kelly’s rear window on Burnett Way. However, that remains a possibility.

Next, Conlin considered the weather conditions that evening. Newspapers confirmed the temperature hit 100 degrees on July 8 and the Union’s hourly breakdown put the temperature at about 75 degrees around the time Sheridan hit the long blow (approximately 11:00p.m.).[fn]Staff reporter, “The Weather” Sacramento Union, 9 July 1953, 1. The twi-night double header of July 8, 1953 started at 7:00p.m. The box score reported the first game was completed in 1:47, which put the conclusion near 8:47p.m. Allowing for a 30-minute break between games, the second contest would have started around 9:15. The second box score reveals it took 2:15 to complete the second game, which concluded approximately at 11:30p.m. Dividing the total minutes of the second game (135) into thirds, the 7th inning began around 10:45. The home half of the inning—when Sheridan hit the long home run—occurred around 11:00p.m., according to our estimations. According to the Sacramento Union temperature readings, at the time of Sheridan’s blast, it would have been approximately 70–75 degrees.[/fn] Mulligan theorized the conditions were “ideally suited for long ball hitting.” He noted that in the first game of the doubleheader, Seals center fielder Al Lyons had been completely fooled on a curve ball thrown by Solons pitcher Ken Gables, “…and with his hips backed out toward the San Francisco dugout,” still managed to clout a 425-foot triple to dead center field.[fn]Bill Conlin, “The Shot Heard Around The World,” Sacramento Union, 12 July 1953, 19.[/fn]

Finally, on Monday, July 13, when the Union reported the Muir & Train measurement of 613.8 feet, the article also noted that an unnamed Solons’ parking lot attendant “heard the impact of shattered glass when the epic circuit clout soared over the left-field wall and entered Kelly’s parked auto by way of the rear window.”[fn]Staff reporter, “Sheridan Homer Checks Out at 613.8 Feet,” Sacramento Union, 13 July 1953, 4.[/fn] That doesn’t prove that Kelly’s vehicle was parked on Burnett Way, however, it does lend credence to his story.

On July 14 Muir & Train produced a letter and a notarized Plat of Survey verifying that the exact distance amounted to 613.80 feet (where “corrections have been made in standard tape length at a temperature of 68 degrees F.”).[fn]Muir & Train, Plat of Survey, 14 July 1953.[/fn] With the notarized documents, Sheridan’s feat had been certified to be the longest home run ever recorded.

Sheridan’s teammate, Bockman, who played four seasons for the Solons and viewed the long home run from the dugout that evening, said, “To see the ball leave the park, you would say that it was going forever. He hit it a long way.”[fn]Eddie Bockman, telephone interview, 2 April 2010.[/fn] Bockman stayed in baseball as a long-time minor league manager and scout, and signed Bob Boone and Larry Bowa for the Phillies.

Local boy Ronnie King, who played in the Cleveland organization and for the Solons, and later worked as scouting supervisor for the Dodgers and Pirates, finds the tale hard to believe. “The story’s been told and embellished over time,” he figures. When told the surveyor certified the measurement, he shakes his head. “To hit a ball 600 feet…” he says and then shoots the interviewer a look of disbelief, “…can’t be done.” King says he saw major league players with recognized, legitimate power like “McCovey, Stargell, Frank Howard, Ernie Lombardi…all hit for big power and yet none of them came close to hitting a ball 600 feet.”[fn]Ron King, personal interview, 6 April 2010 Staff reporter.[/fn]

Cuno Barragan, another Sacramento native, former Solon and Chicago Cub, had a similar reaction. “We know it was a long home run. [But] six-hundred-and-something feet is pretty hard to justify, in my mind. That’s two ball fields!”[fn]Cuno Barragan, personal interview, 15 November 2010.[/fn] Ironically, just below the Bee’s July 10 story citing Sheridan’s home run was a report about Solon farmhand Barragan colliding with his Idaho Falls teammate (and manager), Red Jessen, resulting in Cuno’s fractured cheekbone and an overnight stay in the hospital.[fn]Staff reporter, “Solon Farm Hands With Idaho Team Suffer Injuries,” Sacramento Bee, 10 July 1953, 26.[/fn]

Like a Fourth of July firework, the Sheridan story shot to national prominence in July 1953, then smoldered for decades until Sacramento baseball historian and memorabilia collector Alan O’Connor came into possession of two important documents from the former president and owner of the Sacramento Solons, Fred David.

Prior to his passing in 2009, David gave O’Connor the letter summarizing the surveying firm’s findings on Muir & Train letterhead. In addition, he presented the Plat of Survey, which had been rolled up, folded, and tucked behind a desk in David’s office until O’Connor opened it. Despite the wrinkles and folds, the document is in excellent condition. It shows the flight of the ball from home plate at Edmonds Field to the “X” marking the location of Kelly’s parked car on Burnett Way, with the distance measured at 613.80 feet. The document is signed by all the principals: Sheridan, Muir, Train, Lincoln Ong (a witness who worked at the surveying firm), and the notary, Donald N. Runyan.[fn]Muir & Train, Plat of Survey, 14 July 1953.[/fn]

While everyone who witnessed Neill Sheridan’s home run can vouch that it was a majestic blow, no one could verify where it actually landed. Apparently, Pat Kelly did not have a companion that night to support his claim. Those involved in the story—from the Solons’ president to the surveying team—took Kelly’s word that he had parked his car that evening in front of 1316 Burnett Way, the home of the Segura family. We know this is precisely the spot because in his July 12 column, Bill Conlin wrote, “By coincidence, the latter’s car [Kelly’s] was just across the street from the home of Mrs. Alice Lightfoot, the head usheret (sic) at Edmonds Field.”[fn]Bill Conlin, “The Shot Heard Around The World,” Sacramento Union, 12 July 1953, 19.[/fn] Public records verify that Lightfoot resided at 1317 Burnett Way, directly opposite the Segura residence. Both homes at that time bordered the east entrance of the Solons’ parking lot.[fn]Sacramento City Directory, 1953, Street section, 184.[/fn]

Mrs. Nancy (Segura) Williams currently lives in the Segura family home, which today shares a property line with a Target Store, located on the former ballpark site at Riverside Boulevard and Broadway. She verified that in the late forties and fifties Solons patrons often parked their vehicles in front of her family’s house before games and slipped through the Solons’ parking lot on the way to the ballpark.[fn]Nancy Williams, personal interview, 16 April 2010.[/fn]

Those who disbelieve the possibility of a 600-foot home run have posited that Kelly’s vehicle might have been parked in the Solon parking lot and the man later embellished his role by bringing Solons’ executives to the Burnett Way location. From the Union photograph of him sitting inside the vehicle on the rear bench seat, Kelly appeared to be middle-aged, possibly older.[fn]Photo caption “Pat Kelly, a baseball fan…” Sacramento Union, 12 July 1953, 19.[/fn] A mature adult, one assumes, would be less likely than a thrill-seeking teenager to concoct a Zelig-type story, especially in the Eisenhower era. However, there remains the possibility that Pat Kelly fabricated the story.

Take for example the scant details that were published about Kelly. When this author attempted to verify his residence at 2928 Broadway, as was twice reported by the Union, we were unsuccessful and came to the conclusion that he could not have lived there because throughout the 1940s and early fifties the address didn’t exist. That section of Broadway served as a commercial district, and in 1953 the two closest enterprises on that block were a used car lot (2920 Broadway) and a former restaurant (2930 Broadway) with no structures listed in between.[fn]Sacramento City Directory, 1953, Street section, 153.[/fn] Fire insurance maps also show the structures were single story, negating the possibility of an upstairs residence.[fn]Sanborn Fire Insurance Map, Sacramento, 1953.[/fn] It is possible the Union incorrectly reported Kelly’s address, but we give the benefit of doubt to sports editor Conlin.[fn]Sacramento City Directory, 1952, Alphabetical section, 412.[/fn]

More importantly, a check of the Sacramento City Directories for that time period show that no Patrick Kelly was even listed in 1953. The name does appear in the 1952 directory, with a “Patk. Kelly” residing at 910½ 2nd Street in Sacramento, however, that is across town from Broadway.[fn]Sacramento City Directory, 1952, Alphabetical section, 412.[/fn]

Another contrasting piece of evidence is this: in a telephone interview Mr. Sheridan recalls that when Kelly presented him with the ball in the clubhouse, the man told him that at the time of the home run “…he was sitting on the front porch, it was an evening game, ideal in Sacramento to sit on the front porch and listen to the ball game, if you weren’t there. That’s what [Kelly] was doing, listening to the radio. And the ball went through the back window.”[fn]Neill Sheridan, telephone interview, 2 April 2010.[/fn] Newspaper accounts referred to Kelly as a spectator who had attended the game on July 8.

Train, formerly of the surveying company, remembers the day when his company performed the service for the Solons. He did not indicate meeting Pat Kelly or seeing a car with a demolished rear window parked there on the street.[fn]Timothy S. Train, telephone interview, 9 April 2010.[/fn] Apparently, Solons officials pointed to the location where Kelly claimed he parked his vehicle on the evening of July 8. (Mr. Train is retired and lives in Phoenix. His former Sacramento firm is now called Train Sening & Hoffman Surveying.)

Finally, since the original story unfolded that summer of 1953, the man who claimed the ball broke his car rear window—Pat Kelly—never resurfaced in the Sacramento area, at least publicly.

Still, all of that doesn’t detract from Neill Sheridan’s historic achievement at Edmonds Field. On that warm summer night, he outraced an Arabian horse, clubbed an opposite-field homer to right field, and then hit the longest professional home run ever measured into the Sacramento skyline.

And he has the ball to prove it.

RICK CABRAL is a Sacramento baseball historian and the founder/editor of BaseballSacramento.com. He has published numerous articles in the “Sacramento Bee” and “Sacramento News & Review” on topics ranging from the 1927 Bustin’ Babes–Larrupin’ Lous barnstorming tour to the only appearance by the New York Yankees in Sacramento when they played an exhibition contest in 1951 against the Solons.

ACKNOWLEGDEMENTS

Thanks to Sacramento historian Alan O’Connor for sharing his resources on the Sheridan home run, and Chris Lango, a Sacramento independent video producer, who assisted in the research of the subject.