Norman L. Macht: My Experiences as a General Manager in the 1951 Georgia-Alabama League

This article was written by Norman Macht

This article was published in When Minor League Baseball Almost Went Bust: 1946-1963

I arrived in Atlanta in the spring of 1948 to work as a statistician and gofer for Atlanta Crackers broadcaster Ernie Harwell and at the radio station that carried the Crackers’ games. I was 18. Midway through the season, Harwell was traded to the Brooklyn Dodgers for a catcher, Cliff Dapper, who became the Crackers’ manager in 1949 and lasted one season. I continued to work for Harwell’s successors.

I arrived in Atlanta in the spring of 1948 to work as a statistician and gofer for Atlanta Crackers broadcaster Ernie Harwell and at the radio station that carried the Crackers’ games. I was 18. Midway through the season, Harwell was traded to the Brooklyn Dodgers for a catcher, Cliff Dapper, who became the Crackers’ manager in 1949 and lasted one season. I continued to work for Harwell’s successors.

Atlanta was a favorite stop for teams traveling north from spring training in Florida. Part of my job was to go to the hotel where they were staying in the morning and get the day’s starting lineup from the manager. You might be surprised -as I was -at how some managers looked when they were not in uniform. That was the first year Jackie Robinson was with the Dodgers when they traveled through the South and stopped in Atlanta, an exciting -and peaceful -historical event at Ponce de Leon Park.

The Crackers, owned by Coca-Cola, were a mainstay of the Double-A Southern Association, an independent team until 1950, when they began a working agreement with the Boston Braves. The front office included three men, a concessions manager, and one scout. Situated at the back of the grandstand behind home plate, their quarters consisted of a small reception area that led to three small offices.

In 1950 I asked the club president, Earl Mann, for a job so I could learn something about the business end of baseball. He hired me as a receptionist and kept me busy with paperwork and helping the concessions manager. I continued to work for broadcaster Jim Woods, who had replaced Harwell.

At the end of the season, Earl Mann told me a team in the Georgia-Alabama League was looking for a business manager. Was I interested? I went down to Lanett, Alabama, to interview for the job and began the following spring. I don’t recall the salary; I would guess it was somewhere around $30 a week (at a time when the average weekly salary for a White male was about $60). It was enough for my wife and me to live on. The job would last until October.

The Georgia-Alabama League was a Class-D minor league, the lowest classification. It had been organized in 1946 and consisted of six teams located in southern Georgia and eastern Alabama. The Chattahoochee River served as the border. In 1951 the teams were located in Opelika, Lanett, and Alexander City in Alabama, and LaGrange, Rome, and Griffin in Georgia. My wife and I rented the entire second floor of a rambling house in West Point, Georgia, just across the river from Lanett.

The area was dominated by textile mills, by far the largest employers. The Valley consisted of a string of towns: West Point in Georgia and Fairfax, Langdale, River View, and Shawmut in Alabama, along the Chattahoochee River. West Point was the biggest town, with a population of about 7,500. The only team with a major-league affiliation was the LaGrange Yankees.

The team was owned by the West Point Manufacturing Company, whose president, Robert Rearden, was also the team president. Although operating at a break-even or profit was desirable, it was not the primary concern. Providing a source of entertainment for baseball fans among the mills’ employees was the priority.

The ballpark, Jennings Field, was located in Lanett. It consisted of an all-wood grandstand behind home plate, and bleachers that ran beyond first base and third base. There were no outfield bleachers. I would guess our capacity was about 1,000; our average attendance was about 600. An employee of the textile mills was the sole groundskeeper, cutting the grass with a lawn mower. I was the only other full-time employee.

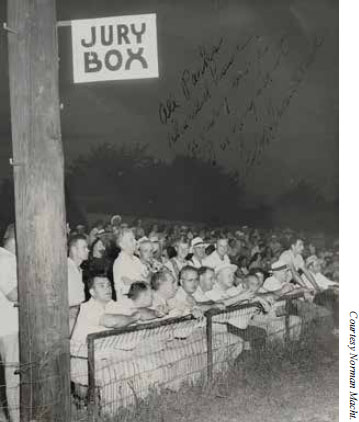

The Jury Box. Lanett had a vocal group of fans, who situated themselves along the third-base line, and supported the home team, by ragging on the umpires and opposing team’s players. (Courtesy of Norman Macht)

There were no overnight road trips, only home-and-home series. The team would ride in a bus that was used by the school district during the day, with a driver who took them out of town and returned after the game. I occasionally rode with them, which is how I saw our 19-year-old pitcher Gene Black throw a no-hitter in LaGrange.

My duties included dealing with the paperwork of contracts, giving talks at civic clubs, hiring ticket sellers and concessions stands personnel (my wife sold the scorecards at the entrance), selling ads for the fences and scorecards, buying supplies for the peanuts and popcorn and snow cones and drinks (no beer), checking the concessions and ticket sales receipts (putting the sticky dimes from the snow cone sales into wrappers for the night deposit bag), and mixing with the fans during the game.

I did not have to find players or a manager. They had already signed a manager: 29-year-old Perley Grant, a veteran minor-league catcher who had never gone higher than the Class-A South Atlantic League. The team was a mix of veterans and youngsters; about half of them were year-round mill employees in their 30s who had played for the Rebels since the league began in 1946, were good hitters, and local favorites. Others were friends of Grant’s from the Sally League. None of them made it to the major leagues.

We had a good, hard-hitting team and finished 64-52, four games back of pennant-winning LaGrange.

As an admirer of Bill Veeck, I came up with promotions: a Miss Valley Rebel beauty contest; farmers’ night, complete with a milking contest and greased-pig chase; and an Opening Day parade of players riding in convertibles through the Valley, while a pilot and I flew overhead in a Piper Cub and I dropped leaflets with free admission coupons from an open door (and turned green in the process).

I had an idea to try to set a Class-D single-game attendance record, but had a problem: I didn’t know what the record was. Sol wrote to The Sporting News and asked if they knew. They didn’t, but they ran an item in the June 6 issue about our inquiry. You can look it up. We received no response.

There was a space near home plate along the third-base line where a group of rabid and vocal fans gathered, standing, at every game. I put some folding chairs there and hung a sign on the nearby light pole that said JURY BOX. One night during a trip through the South, George Trautman, the head of the minor leagues, came to a game and eagerly joined the Jury Box fans.

I learned a lesson in labor relations -literally. I had inherited a public-address announcer, a middle-aged man who I thought lacked the enthusiasm that the job required. I wanted to replace him, but wiser heads at the textile mill suggested I reconsider: The announcer was the club president’s son-in-law. He stayed. None of the club’s officers gave me any problems.

My job lasted until October. Three months later I started a new job, with the US Air Force, that lasted four years. Unrelated to my temporary departure from baseball, the Georgia-Alabama League also went out of business.

NORMAN L. MACHT is the author of 36 books, including a three-volume biography of Connie Mack. His most recent book, They Played the Game, was published in 2019. He is currently writing for the baseball history website peanutsandcrackerjack.com.

Acknowledgments

This article was edited by Marshall Adesman and fact-checked by Mike Huber.