Norman Rockwell’s The Three Umpires

This article was written by Ron Backer

This article was published in Fall 2023 Baseball Research Journal

It may be the most famous baseball painting of all time. Created by Norman Rockwell, it goes by many different names, including The Three Umpires, Game Called Because of Rain, Tough Call, and Bottom of the Sixth. It depicts a baseball game between the Pittsburgh Pirates and the Brooklyn Dodgers at Ebbets Field in Brooklyn. According to the scoreboard, the game is in the bottom of the sixth inning, with Pittsburgh leading, 1–0. The Pirates scored their only run in the top of the second inning. The three umpires of the title are standing together, looking at the skies. The home plate umpire is in the center of the trio, with his hand out to determine how hard it is raining, trying to decide whether or not to call the game. If the umpires call the game, Pittsburgh will win, since the game became official with the completion of the fifth inning and Pittsburgh is still leading. To the right and behind the umpires, the managers from each team are in a heated argument, although it is not clear what the dispute is about. In the distance, three Pirates fielders are shown.1

The original painting is in the collection of the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum in Cooperstown, New York, where it is a favorite attraction for visitors.2 The Three Umpires is so famous, it has become a part of pop culture, and has been printed on a variety of commercial products, including whiskey bottles, ties, watches, and clothing.3 In 1982 it even appeared on a postage stamp of the Turks and Caicos Islands, a British overseas territory.4 Numerous prints of the painting are still being sold to this day.

This is the story of The Three Umpires, a painting which has intrigued baseball fans and others since its first publication on the cover of the Saturday Evening Post over 70 years ago.

NORMAN ROCKWELL

Painter and illustrator Norman Rockwell was born in New York City on February 3, 1894. Rockwell displayed a natural ability for drawing as a youngster and after attending several art schools to hone his craft, embarked on a professional career while still a teenager. He completed his first commissioned works before he was 16 (four Christmas cards for a client), illustrated his first book when he was 17, became art director of Boy’s Life magazine when he was 19, and produced a cover for the Saturday Evening Post when he was just 22.5 The latter is most significant because, despite numerous drawings and paintings for calendars, advertisements, commercial products, collectibles, and story illustrations, Rockwell is most famous today for his magazine covers. His works appeared on the front of virtually every major magazine, including Life, Look, Literary Digest, and McCall’s.6 But none rival the Saturday Evening Post, where Rockwell produced 323 covers over 47 years.7

Rockwell’s works usually depict aspects of Americana, often renderings of his real or imagined views of bygone eras, but sometimes contemporary subjects such as Rosie the Riveter (Saturday Evening Post, May 29, 1943), a painting about a female industrial worker on the job during World War II, and The Problem We All Live With (Look, January 14, 1964), a civil rights painting about a young African American girl integrating a Southern school. Rockwell drew numerous works about baseball, from illustrations for advertisements and short stories to paintings for magazine covers, the latter primarily for the Saturday Evening Post. Among his most famous Post baseball covers are The Dugout (September 4, 1948), showing an upset Cubs’ dugout presumably during a losing game being jeered at by the fans in the stands above, The Rookie (Red Sox Locker Room) (March 2, 1957) about a new player in a hat and suit, holding a suitcase and a bat in his hands, arriving in the Red Sox locker room and looking very out-of-place, and Knothole Baseball (August 30, 1958), depicting the view of an amateur or low-level professional game through a small hole in a fence.

By the mid-1930s, Rockwell usually painted his magazine covers from black and white photographs, first making a rough pencil sketch of the proposed work and then after obtaining preliminary approval from a publication, finding models he could pose in the positions he needed for the painting.8 (The models were often his friends or neighbors.) He then created several preliminary drawings of the painting, known as studies, including a detailed, full-size charcoal sketch of the work and then a small color sketch, before proceeding to the final work, which was oil on canvas.9

Norman Rockwell died on November 8, 1978, at the age of 84, in Stockbridge, Massachusetts—the future location of the Norman Rockwell Museum. In a career that lasted more than 60 years, he produced over 4,000 original works of art.10

THE CREATION OF THE THREE UMPIRES

On September 14, 1948, before the first game of a doubleheader between the Pittsburgh Pirates and the Brooklyn Dodgers, Norman Rockwell brought a professional photographer to Ebbets Field in Brooklyn for the purpose of taking reference photos of umpires, managers, coaches, and players to aid in the painting of The Three Umpires. Rockwell chose the individuals to be depicted in the painting and posed them as he expected them to appear in his work. He also had reference photos taken of the Ebbets Field scoreboard. There are numerous reference photos from that day in the archives of the Norman Rockwell Museum, twelve of which are available for viewing on the museum’s website.11

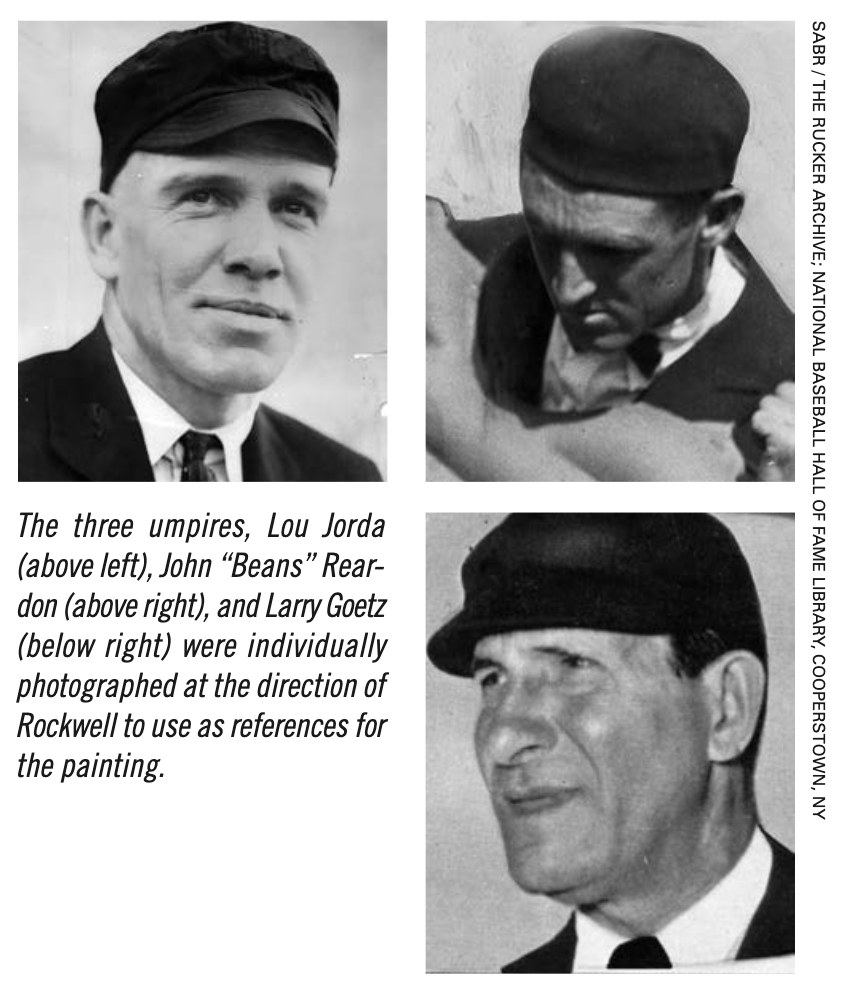

Despite the three umpires being grouped in the painting and the managers being face-to-face, reference photos were taken of each those models separately. Rockwell had such a strong image of the painting in his mind that even though not one bit of paint had yet been applied to canvas, he seamlessly blended the individuals into groups in the painting.

Because of the availability of the reference photos, the detail in the painting, and a blurb in the Saturday Evening Post, the five prominent individuals in The Three Umpires are easily identifiable.

The home plate umpire extending his hand is John “Beans” Reardon. Reardon umpired in the National League from 1926 to 1949—including five World Series and three All-Star games—before leaving the profession at age 52 to manage a beer business. He is one of the most memorable umpires in the history of the game, both for his tendency to swear at the players when he argued with them and for the great stories he told even after he left the game.

Reardon also had a unique look, wearing a distinctive blue and white polka-dot bowtie (instead of the usual necktie used in the National League at the time), although there is little detail of it in The Three Umpires. Prominent in the painting is the inflated, American League chest protector then worn by Reardon even though Reardon was a National League umpire, and he was supposed to wear a smaller chest protector underneath his coat.12

To the left of Reardon is base umpire Larry Goetz. Goetz umpired in the National League from 1936 to 1956, appearing in three World Series and two All-Star games. To the right of Reardon is base umpire Lou Jorda, who umpired in the National League from 1927 to 1931 and again from 1940 to 1952. He worked in two All-Star Games and two World Series. Jorda is wearing the traditional necktie in the painting.

The Pirates manager is Billy Meyer. Meyer managed the Pirates for five seasons (1948–52), with his teams finishing in the first division in only one year and finishing in last place in two seasons. His Pirates team in 1952 lost 112 games, still the seventh worst finish by average (.273) in the combined history of the American and National Leagues from 1901 to 2022. Clyde Sukeforth, a Dodgers coach, is the person arguing with Meyer. As a scout, Sukeforth was instrumental in bringing Jackie Robinson to the Dodgers and Roberto Clemente to the Pirates. As an interim manager for the Dodgers in 1947, he managed Jackie Robinson in his first two games in the big leagues.13 (The identities of the three Pirates players in the painting will be discussed below.)

Even though Rockwell had already visualized the painting before arriving at Ebbets Field, he was not wedded to his original conception. For example, there are no reference photos of the two outfielders in right field taken on September 14, 1948 at Ebbets Field, and as will be discussed later, it seems likely that Rockwell decided to add the outfielders to his painting sometime after September 14, 1948. The two outfielders enhance the picture, keeping right field from being empty and boring, and balancing the second baseman to the left of the umpires.

Rockwell also changed the portrayal of Clyde Sukeforth. In the available reference photos, he is holding his cap in the hand above his head and his lower hand is empty, perhaps stretched out to feel the rain. In the final painting, the cap is in his lower hand and his upper hand has a finger pointing to the sky. It is unknown why Rockwell made these changes.

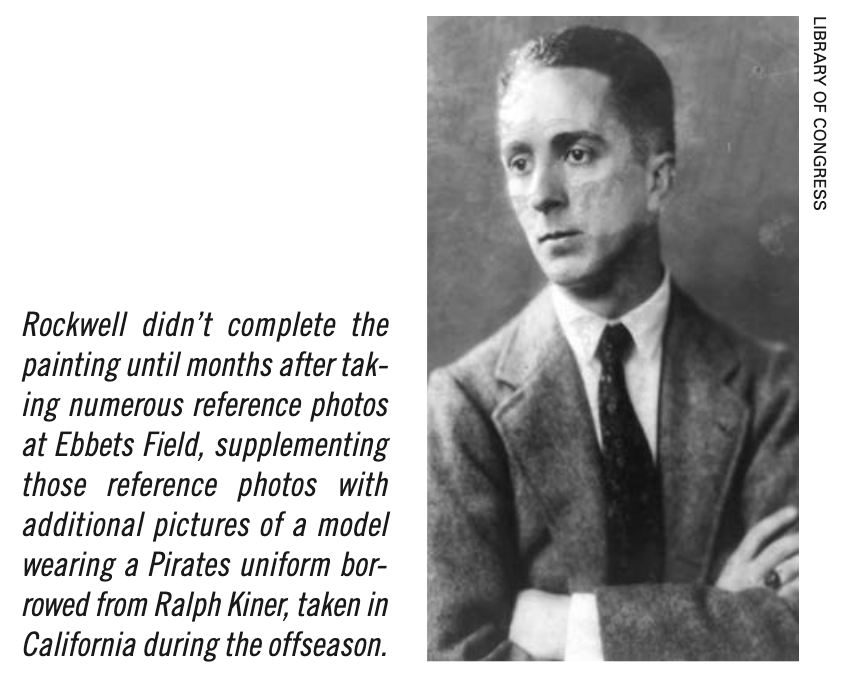

Norman Rockwell took the reference photographs to California, where he and his family spent the winter, and completed the painting there. Ralph Kiner, the Pirates slugging outfielder, also wintered in California. During that offseason, Rockwell called Kiner and asked him if he happened to have his Pirates uniform with him. Kiner did, because he had played in an exhibition-game tour after the regular season. Rockwell visited Kiner to look at the unform, as a reference for Billy Meyer’s uniform. Rockwell later gave one of his original drawings to Kiner, for his help on the painting.14

The Three Umpires appeared as the cover of the April 23, 1949, issue of the Saturday Evening Post. As with most of Rockwell’s covers for the magazine, the painting is unrelated to any story in the issue.

When Rockwell first viewed the published cover, he was quite surprised. The Saturday Evening Post had made changes to his painting without consulting him. One of the changes, the alteration of the “GEM” (razor blade) advertising on the outfield wall to the generic “SCM” is understandable (although Rockwell should have been consulted), because the Post hardly wanted to give free advertising on its cover to a consumer product, and there could have been trademark or copyright issues. The other changes were much more problematic. The Post changed Rockwell’s dark gray clouds along the entire top of the painting into a blue sky with lightened gray and white clouds on the top right of the painting. It also darkened the Pirates’ uniforms.

An upset Rockwell wrote to Ken Stuart, the art editor of the Post who had authorized the changes, disputing his decisions and telling him that the sky “was better as I conceived and painted it.”15 Because this was the fourth time the Post had altered one of Rockwell’s paintings without his approval, “completely unethical” conduct according to Rockwell, the painter wrote, “I cannot go on painting with any strength or conviction with the threat of such changes to my work constantly hanging over my head.”16 The Post thereafter changed its protocols, at least with regard to Rockwell’s work, requiring additional editors to approve any changes to his paintings and to consult with Rockwell before any changes were actually made.

ANOMALIES, CONTROVERSIES, AND INTERESTING FACTS

The Umpires

One of the apparent anomalies in The Three Umpires is that, in accordance with the title, there are only three umpires depicted, instead of the usual four. This was not, however, an error on Rockwell’s part. Although four umpires were used in the World Series as early as 1909, a four-man crew was not officially instituted for all regular season games until 1952.17 And, in fact, there were only three umpires officiating the Pirates-Dodgers doubleheader on September 14, 1948, the day the reference photographs were taken. This was a bit of luck on Rockwell’s part. With only three umpires in the painting, the two base umpires provide a balance to the much larger home plate umpire in the middle. With four umpires, the picture would have been unbalanced and the home plate umpire would not have been the center of attention, as he is supposed to be.

Of course, baseball was played with more than three players on the field in 1948, but Rockwell chose to include only three in his painting. This falls into the category of artistic license. If there were nine players on the field, the painting would have been cluttered and the viewer’s eye would have drifted away from the focus of the work—the three umpires and the tough call to be made. Similarly, while many people have commented that the scoreboard in the painting does not match any of the action in either game of the doubleheader that was played on September 14, 1948, Rockwell was not chronicling any specific game in his work. He used the real players, umpires, and coaches who were on the field that day only as a reference for a drawing which sprang entirely from his imagination.

Burt Shotton

In September 1948, the Dodgers manager was Burt Shotton, but it is coach Clyde Sukeforth who is shown arguing with Pirates manager Billy Meyer just behind the trio of umpires. This anomaly is easily explained. Burt Shotton was one of the last of the big-league managers who did not wear a uniform during the game. While in the dugout, Shotton usually wore a suit, although on some occasions, he wore a warm-up jacket or windbreaker with “Dodgers” across the front and a team cap. On warmer, sunnier days, he sometimes wore slacks, a sports shirt, and a wide-brimmed hat.18 Thus, Shotton could hardly be used as the model for the Dodgers manager in Rockwell’s painting, since a man in street clothes would have seemed out of place. Although there is no specific major league rule that requires a manager to be in uniform, Shotton was apparently not allowed on the field because he did not wear a uniform. During games, Shotton used two of his coaches, either Clyde Sukeforth or Ray Blades, to argue calls with an umpire or replace a pitcher.19 Sukeforth, the better-known of the two, was the obvious individual to substitute for Shotton in the painting.

The Sprinkle Painting

Sandra Sprinkle, the granddaughter of Beans Reardon, passed away in 2015. Years before, she had placed what she thought was a signed print of The Three Umpires above the fireplace mantle of her home in Dallas, Texas. Sandra had obtained the artwork through inheritance. After Sandra’s death, her husband, Gene Sprinkle, moved to a retirement community. In the process of downsizing, Gene’s nephew emailed photos of Reardon memorabilia in Gene’s possession, such as National League season passes, original photos, signed baseballs, and the Rockwell print, to an auction house. Since the print was signed by Rockwell, they believed it had, at least, a little value.20 During this process, the nephew took a closer look at the Rockwell artwork and noticed brushstrokes. Could the print actually be an original painting by Rockwell? The auction house, along with some experts, thoroughly examined the piece and agreed—this was no print. It was an original, unknown painting by Rockwell.21 On August 19, 2017, the painting, previously thought to have little value, sold at auction for $1.68 million.22

Sprinkle’s painting was actually the Rockwell color study of The Three Umpires. The study is oil on paper, 16 x 15 inches.23 (The final painting, which is oil on canvas, is much larger, 43 x 41 inches.24) The study is incomplete, with the scoreboard essentially just a blue rectangle, the skies blue and cloudless, and the two outfielders missing.25 The newly found work is signed and inscribed in the lower right as follows: “My best wishes to ‘Beans’ Reardon, the greatest umpire ever lived, Sincerely, Norman Rockwell.”26

The Three Pirates Players

As noted before, the umpires, the Dodgers coach, and the Pirates manager are easily identifiable in the Rockwell painting. The three Pirates players are not. Their figures are so small that their faces are unrecognizable.

It seems logical that the two Pirates on the back right of the painting are the Pirates’ right fielder and center fielder, talking to each other during a break in the action. The playing position of the third fielder is more difficult to determine. Given his small size and what appears to be his proximity to the outfield wall, many have concluded that he is the left fielder. In fact, he is the second baseman, standing some distance from the outfield wall. In the painting, the third player appears to be taller than the two outfielders in right field, meaning that the player is standing closer to home plate than an outfielder would. From the perspective of the viewer, the third player is standing in line with the left side of the Ebbets Field scoreboard, which was located in right field of the stadium. Only the second baseman would logically be standing in the position shown in the painting.

Given the conclusion that the players depicted are the right fielder, center fielder, and second baseman, historian Larry Gerlach, in his seminal article on Norman Rockwell’s baseball paintings, “Norman Rockwell and Baseball Images of the National Pastime,” wrote that the players in the painting are Pirates right fielder Dixie Walker, center fielder Johnny Hopp, and second baseman Danny Murtaugh.27 While there is logic to that conclusion, there are no independent facts to support the contention that Walker, Hopp, and Murtaugh were the models for those players, partly because there are no available reference photos of the two outfielders taken at Ebbets Field on September 14, 1948.28 There are two reference photos for the infielder which were taken at Ebbets Field on that day. One shows a side view of the player and in the other, the player’s eyes are obscured by the shadows caused by his cap. It is therefore difficult to determine who the player is, but he does not appear to be Danny Murtaugh. In particular, the nose and chin of the player in those two reference photos are dissimilar to Murtaugh’s. Based upon the side view of the fielder in one of those reference photos, Rockwell may have originally intended to paint a shortstop or a third baseman to the left of the umpires, a further indication that the model was not Murtaugh.

After review of all of the reference photographs in the files of the Norman Rockwell Museum, it is clear that one person served as the model for the infielder and both outfielders. The files contain three reference photos of an unknown ballplayer in a Pirates uniform, taken not at Ebbets Field, but in a location in which the player is standing in front of a tree and a car.

In one of those three reference photos, the player is standing at the exact angle and in the exact pose as the second baseman in The Three Umpires, although he does not have a glove in his hand. In another, he is shot from a side view, in almost the exact pose of the right fielder in the painting, again without a glove. In the third photo, the player is posed just like the center fielder, this time with a glove in his hand. These are undoubtedly the reference photos that Rockwell used to paint all of the fielders in The Three Umpires, not the two photos that were taken at Ebbets Field.

It is plausible to conclude that Rockwell was unhappy with the two reference photos of the infielder taken at Ebbets Field, perhaps because the infielder’s face in the photos was partially obscured from view. Around the same time, Rockwell must have decided to add the two outfielders to the painting. He therefore needed additional reference photos, which required a new model and a Pirates uniform. Since it was too late to go back to Ebbets Field and use multiple models, Rockwell must have decided to use only one model for all three fielders in the painting.

Who was the model for the new reference photos? It could be a different Pirates player, appearing in photos taken when the team returned to Brooklyn just a week after the original reference photos were taken. While the timeline fits, it is difficult to match the face of the model with any of the players on the 1948 Pittsburgh Pirates roster. A more likely possibility is that the three new reference photos were taken some time later in California, where Rockwell completed the painting, with a model who may or may not have been a ballplayer, wearing a Pirates uniform borrowed from Ralph Kiner.29 There appear to be palm trees in the background of the photos, a likely indicator of California.Without any available documentation addressing the issue, all of this is conjecture. The identity of the model for the Pirates fielders used in The Three Umpires may never be known. It is clear, however, that Dixie Walker, Johnny Hopp, and Danny Murtaugh were not the models for those players.

The Scoreboard

There are no Brooklyn players depicted in The Three Umpires. However, the batting order on the scoreboard indicates that No. 35 is playing left field, and No. 42 is playing second base. Those are the uniform numbers of left fielder Marv Rackley and second baseman Jackie Robinson, respectively. The reference photos and the painting indicate that Rackley led off that day and Robinson batted second, and that was, in fact, the batting order for both games of the doubleheader. There was also a place on the Ebbets Field scoreboard for the insertion of the number of the player who was then batting, but since the reference photos were taken before the games started on September 14, 1948, that space has a “0” in it in the photos. However, in the painting, Rockwell inserted No. 20 into that slot.

Three different players wore No. 20 for the Dodgers that year, including pitcher Elmer Sexauer, who was on the roster in September. However, Sexauer, who only pitched in two innings for the Dodgers that year, did not play in either game of the doubleheader on September 14, 1948.30 It is unlikely that Rockwell was familiar with Sexauer and so, in this instance, Rockwell apparently randomly chose a uniform number for the “at bat” slot on the scoreboard, one which did not accurately reflect any ballplayer in the lineups that day for Brooklyn.

Rockwell made one mistake in his painting of The Three Umpires. On the real scoreboard, there are two lines at the bottom for the insertion of the batting orders of both teams. When the reference photos of the scoreboard were taken before the games on September 14, 1948, only the Dodgers lineup was on the board.31 Rockwell re-created a part of that line in his painting by including the numbers of Marv Rackley and Jackie Robinson in the correct order in the Brooklyn lineup, as shown in the reference photos. The Pittsburgh lineup was not shown in the reference photos, probably because they had not yet been provided to the scoreboard operator. However, by the bottom of the sixth inning, the Pirates lineup would have been displayed on the scoreboard, and Rockwell should have included at least a part of the lineup in his painting, which he neglected to do.

The Controversy

The primary controversy about The Three Umpires is that Clyde Sukeforth, the Brooklyn coach, is smiling, while Billy Meyer, the Pirates manager, is frowning. Yet, if the game is called because of rain, the Pirates will win the game. Shouldn’t their demeanors be reversed?

This incongruity was so worrying to the editors of the Saturday Evening Post that they addressed it on page 3 of the same issue in which The Three Umpires was published. In a paragraph titled “This Week’s Cover,” they first acknowledged that if the arbiters call the game, Pittsburgh will win. They then stated that this “irks the Brooklynites, who dislike having other teams win.” They then opined that Clyde Sukeforth could well be saying, “You may be all wet, but it ain’t raining a drop!” Bill Meyer is doubtless retorting, “For the love of Abner Doubleday, how can we play ball in this cloudburst?”32 Whether that imagined conversation justifies the expressions of Sukeforth and Meyer in the painting is for others to decide.

Another theory, suggested by Gerlach, is that since the score in any half inning was not inserted into the scoreboard at Ebbets Field until the inning was over, even if runs had been scored in the inning, there is a possibility that Brooklyn had already scored two runs in the bottom of the sixth inning, but the scoreboard had not yet been updated to reflect that fact. In that case, Brooklyn would win the game if the umpires called it because of rain.33 This contention seems to be too much “inside baseball” to be convincing, as it is hardly likely that Rockwell would have been cognizant of this practice in Brooklyn, or that Rockwell thought about it weeks later when he was painting the picture in California. In any event, if Rockwell had intended that Brooklyn was winning the game at the time of the tough call, why not simply make the scoreboard read 2–1 in favor of Brooklyn?

Among the other theories is one suggested by art critic Christopher Finch, who has argued that Clyde Sukeforth is happy because the rain is about to stop and the game will continue, giving Brooklyn a chance to win.34 While an intriguing interpretation, it is unlikely that the three Pirates fielders would have remained on the field during a rainstorm, and it is more likely that the rain has just started. Also, since Rockwell’s final version of his painting showed dark clouds in the sky, before the editors of the Saturday Evening Post modified it without Rockwell’s consent, it seems clear that at least from Rockwell’s perspective, the rain is not about to end any time soon.

Others have argued that Sukeforth and Meyer are merely acting out their differing positions concerning the rain. Sukeforth, with a maniacal expression on his face, has his cap off and is pointing to the skies, demonstrating to Meyer that it is not raining. The hunched-over Meyer, hands to his chest, seems to be showing Sukeforth that he is cold and wet, requiring the calling of the game for the health of everyone involved.

All of these explanations are possibilities. Rockwell often left ambiguities in his paintings, which made them subject to multiple interpretations, but also made them much more interesting. The interpretation of the expressions of Billy Meyer and Clyde Sukeforth in The Three Umpires is in the eye of the beholder.

OBSERVATIONS AND CONCLUSION

By painting the umpires from below, Rockwell made the arbiters into giants. They tower over the other people in the painting and even over the scoreboard and outfield fence. This makes the umpires the most important people on the field both symbolically and actually, because they are the ones who will make the tough call. The fact that Beans Reardon wore a balloon chest protector on the outside of his coat was fortunate for Rockwell. The insertion of the large protector in the most prominent spot in the painting adds interest to the already interesting tableau of umpires, stern and imposing, giving the viewer’s eye a place of focus once the faces of the trio of arbiters and the outstretched hand of Reardon are observed and studied. The oversized chest protector, the largest prop in the painting, also adds to the effect that Rockwell was trying to evoke—the umpires as giants among men.

Norman Rockwell’s baseball paintings are often fascinating because of some unusual aspects of them. Except for his earliest story illustrations, Rockwell seldom showed a batter batting, a fielder fielding, or a runner running. Rockwell was interested in the ancillary aspects of the game, such as the locker room, the dugout, the view of a game through a knothole in a fence, and in the subject piece, the decision by the umpires as to whether or not to call the game because of rain. Is there any other artwork about this particular circumstance in baseball, a circumstance which is unique to the sport? Only Norman Rockwell was able to envision the interest this situation could engender.

Although Rockwell painted portraits, he never painted landscapes or still lifes, being more interested in telling a story than catching a moment in time.35 He once said, “I love to tell stories in pictures. For me, the story is the first thing and the last thing.”36 In The Three Umpires, by providing details about the status of the game on the scoreboard, the tough call by the umpires has become tougher, since if they call the game, Pittsburgh will automatically win, and if they let the game go on, Brooklyn has a good chance of winning, down only one run, with a chance to bat in four more innings. No wonder the managers are in such a heated argument. There is a lot at stake in the umpires’ decision. What will happen? The viewer of the painting has to decide, because although Rockwell is telling a story, it is the viewer who must provide the ending.

Thus, The Three Umpires has fascinated, perplexed, and interested baseball fans and others ever since the painting was first published on the cover of the Saturday Evening Post more than 70 years ago. And there is little doubt that more than 70 years from now, baseball fans and others will still be arguing about the tough call of the three umpires and whether or not the game should be called because of rain.

RON BACKER is an attorney from Pittsburgh who has written five books on film, his most recent being Baseball Goes to the Movies, published in 2017 by Applause Theatre & Cinema Books. He has also lectured on sports and the movies for Osher programs at local universities. Feedback is welcome at: rbacker332@aol.com.

Acknowledgments

My thanks to Larry Gerlach, professor emeritus of history at the University of Utah and past national president of SABR, for answering my questions about The Three Umpires and reading an earlier draft of this article, and to Stephanie Plunkett, Deputy Director/Chief Curator, and Maria Tucker, Curatorial Assistant, of the Norman Rockwell Museum, for their kindness in assisting me in the review of the Museum’s files about The Three Umpires.

Notes

1 The painting may be viewed on the Internet, by searching for “ The Three Umpires” or “Game Called Because of Rain.”

2 “ The Three Umpires (Game Called Because of Rain/Tough Call),” Norman Rockwell Museum Custom Prints website, https://prints.nrm.org/detail/261004/rockwell-the-three-umpires-game-called-because-of-rain-toughcall-1949.

3 Larry Gerlach, “Norman Rockwell and Baseball Images of the National Pastime,” Nine: A Journal of Baseball History and Culture (Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, Fall, 2014), 49.

4 Dominic Sama, “Tributes to baseball from the world over,” Philadelphia Inquirer, March 23, 1986, 236.

5 Thomas S. Buechner, Norman Rockwell: A Sixty Year Retrospective (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1972), 42.

6 Thomas S. Buechner, Norman Rockwell: Artist and Illustrator (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1970), 19.

7 “Norman Rockwell’s 323 Saturday Evening Post covers,” https://www.nrm.org/2009/10/normanrockwells-323-saturday-evening-post-covers/. Other sources give slightly different figures for the number of the Saturday Evening Post covers by Norman Rockwell. See, e.g., Maureen Hart Hennessey and Anne Classen Knutson, Norman Rockwell: Pictures for American People (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1999), 187, n. 16.

8 Ron Shick, Norman Rockwell: behind the camera (New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2009), 16, 23. Rockwell used professional photographers to take the pictures.

9 Norman Rockwell, How I Make a Picture (New York: Watson-Guptil Publications, 1979), 24-27.

10 Encyclopedia of Art, “Norman Rockwell,” accessed May 15, 2023: http://www.visual-arts-cork.com/famousartists/norman-rockwell.htm.

11 Norman Rockwell Museum website, accessed May 15, 2023: http://collection.nrm.org/#details=ecatalogue.55821.

12 Bob LeMoine, “Beans Reardon,” SABR BioProject, accessed May 15, 2023: https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/beans-reardon/. Beans Reardon, Retrosheet, https://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/RZPrearb901.htm.

13 James Lincoln Ray, “Clyde Sukeforth,” SABR BioProject, accessed May 15, 2023: https://13sabr.org/bioproj/person/clyde-sukeforth/.

14 Stan Isaacs, “Kiner-isms liven dull moments,” Asbury Park Press, June 29, 1985, 25. There is a slightly different version of that story, printed in the Pittsburgh Press the same week that The Three Umpires was published on the cover of the SEP. In the Press article, baseball writer Les Biederman wrote, presumably on information received from Kiner, that “Rockwell borrowed a Pirate uniform from Kiner to make it [the painting] more authentic.” Lester Biederman, “The Scorecard,” Pittsburgh Press, April 22, 1949, 41.

15 Norman Rockwell Museum website, accessed May 15, 2023: http://collection.nrm.org/#details=ecatalogue.55821.

16 Norman Rockwell Museum website, accessed May 15, 2023: http://collection.nrm.org/#details=ecatalogue.55821.

17 “Umpiring Timeline,” MLB.com, accessed May 15, 2023: https://www.mlb.com/official-information/umpires/timeline.

18 Rob Edelman, “Burt Shotton,” SABR BioProject, accessed May 15, 2023: https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/burtshotton/.

19 Steven Booth, “The Story of kindly old Burt Shotton,” The Hardball Times, February 4, 2011, accessed May, 2023: https://tht.fangraphs.com/the-story-of-kindly-old-burt-shotton/.

20 David Seideman, “Newly Discovered Version of Norman Rockwell’s ‘Tough Call’ Up To $360K in Auction,” Forbes, August 16, 2017, accessed May, 2023: https://www.forbes.com/sites/davidseideman/2017/08/16/family-discovers-norman-rockwell-baseball-print-is-an-original-painting-worth-up-to-1-million/?sh=bdedd2637124.

21 A copy of the newly discovered painting can be seen on the website of Heritage Auctions, accessed May, 2023: https://sports.ha.com/itm/baseball/1948-original-study-for-tough-call-by-norman-rockwell-gifted-tolegendary-umpire-beans-reardon/a/7195-80067.s?ic4=OtherResults-SampleItem-071515.

22 Bob D’Angelo, “Famous Norman Rockwell study drawing of umpires fetches 1.68M at auction,” Atlantic-Journal Constitution, August 21, 2017, accessed May, 2023: https://www.ajc.com/entertainment/famous-normanrockwell-study-drawing-umpires-fetches-68m-auction/tSEFdANWqq0ipmg4Q2DPZN/. “Norman Rockwell baseball rendering sells for 1.6M,” Atlanta Constitution, August 22, 2017, A2.

23 Heritage Auctions website, accessed May, 2023: https://sports.ha.com/itm/baseball/1948-original-studyfor-tough-call-by-norman-rockwell-gifted-to-legendary-umpire-beans-reardon/a/7195-80067.s?ic4=0therResults-SampleItem-071515.

24 Norman Rockwell Museum website, accessed May, 2023: http://collection.nrm.org/#details=ecatalogue.55821.

25 According to Rockwell, his color sketches were not intended to be the equivalent of a completed work. Rockwell tried not to carry his color sketches so far that there would be no fun left in completing the final paintings. Norman Rockwell, How I Make a Picture (New York, NY, Watson-Guptil Publications, 1979), 156.

26 Rockwell wrote, “Some of my color sketches are, I am sorry to say, better than the finished paintings and I often sell them or give them to friends.” Norman Rockwell, How I Make a Picture (New York, NY, Watson-Guptil Publications, 1979), 153.

27 Gerlach, 49.

28 Hopp, wearing No. 12, does appear in the outfield in one reference photo of the scoreboard, but since he is not standing in the same pose as the center fielder in the painting, that photo is not a reference photo for the center fielder but only for the scoreboard.

29 See note 14, above.

30 “Elmer Sexauer,” Baseball Reference, https://www.baseball-reference.com/players/s/sexauel01.shtml, accessed August, 2023.

31 It is actually the starting lineup from the previous day’s game, September 13, 1948. The only change in the starting lineup between the previous day’s games and the first game of the doubleheader was the pitcher’s spot.

32 Saturday Evening Post, April 23, 1949, 3.

33 Gerlach, 51.

34 Christopher Finch, Norman Rockwell 332 Magazine Covers, New York, NY, Abbeville Press/Random House 1979), 365.

35 Gerlach, 43.

36 Stephanie Haboush Plunkett, Deputy Director, Chief Curator, Norman Rockwell Museum, from her introduction to Ron Shick, Norman Rockwell: behind the camera, (New York, NY, Little, Brown and Company, 2009), 9.