Paper Tigers: How a Player Strike Put a Team of ‘Misfits’ on a Major League Field for a Day

This article was written by Kevin Barwin

This article was published in Spring 2023 Baseball Research Journal

One of the most unusual baseball games in American League history took place at Shibe Park, Philadelphia, on May 18, 1912. Nominally a contest between the Philadelphia Athletics and the Detroit Tigers, the men who suited up for the Tigers that day were locally recruited ballplayers, while the real Tigers players bought tickets to sit in the stands and take in the spectacle. How did this turn of events come to pass?

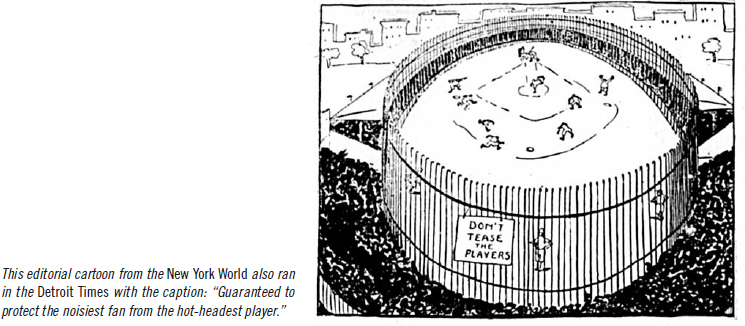

The origins of the crazy contest lie in New York City’s American League Park. commonly known as Hilltop Park. On May 15, 1912, the Tigers were there to play a four-game set with the New York Yankees (nee Americans). Ty Cobb, Detroit’s irascible but extremely talented batsman, had received much vocal abuse in the previous game and the May 15 game was not very different; from the moment Cobb walked on the field New York fans hurled insults and vile epithets at the volatile Tigers star.1 The hot-tempered Cobb, who often fought with opponents and even teammates whenever he felt an injustice had been done to him, seethed under the barrage of verbal abuse. One fan in particular, Claude Luecker—a Tammany Hall clerk who regularly sat behind the home dugout—routinely got on Cobb’s nerves whenever the Tigers came to town.2 On this day Luecker allegedly questioned Cobb’s mother’s race and morals. By the fourth inning Cobb had enough and snapped, leaping over the railing into the stands and pummeling his antagonist. A by stander yelled to Ty, “Don’t kick him, he’s a cripple and has no hands,” to which Cobb replied “I don’t care if the d has no feet.”3 Luecker, a former press man who had lost his left hand and three fingers of his right in a previous workplace accident, described the event to reporters. His account is lengthy, so here are some excerpts:

When the Detroits were in the field in the third inning the boys kept it up on Cobb. Still there was no harm in what was said. I had on an alpaca coat and he seemed to single me out for he yelled back, “Oh, go back to your waiter’s job.”

But that did no harm. [Later] he followed this up with some vile talk. The crowd seemed to be taken back by this but then there was louder booing. I suppose I joined in the rest but there was nothing said at Cobb half as bad as he said himself and he said it firsts.

In the middle of the yells, a man near me called out, “Oh, go on and play ball you half-coon.”

In other games with the Detroits I have seen Cobb who generally gets a good deal of ragging, walk on by the stands across from third base and keep up his talk with the crowd as he went along. Wednesday, after the third inning, it was different. He circled around by first base [Author’s note: he had stood in the carriage lot in the outfield between innings] and then went to the bench of the Detroit players….

Then we saw Cobb followed by a half dozen or more Detroit players each with a bat in his hand start for the section of the stand where we were. Cobb ran over to just the front of where I was and vaulted over the fence. I was sitting in the third row and he made straight for me. He let out with his fist and caught me on the forehead over the left eye. You can see the lump over there now. I was knocked over and then he jumped me. He spiked me in the left leg and kicked me in the side. Then he belted me be hind the left ear.4

Umpire Fred Westervelt and a Pinkerton policeman separated the combatants and Westervelt ordered Cobb from the field.5 American League President Ban Johnson happened to be at the game and witnessed the melee.6 The game continued and Detroit won, 8-4. That evening the Tigers travelled to Philadelphia for a Thursday contest with the Athletics, but that game was rained out. On the evening of May 16, Detroit manager Hughie Jennings received word from President Johnson that Cobb was suspended indefinitely for the Wednesday incident.7

Jennings had no comment, but Cobb thought he had been treated unfairly. “I should at least have had an opportunity to state my case. I feel that a great injustice has been done.”8

On Friday, May 17, the Tigers, without Cobb, toppled the Athletics, 6-3. That day the Tigers players gathered at the Hotel Aldine and signed an agreement that they forwarded to President Johnson and also released to the press:

Feeling that Mr. Cobb is being done an injustice by your action in suspending him we, the undersigned, refuse to play in another game after today until such action is adjusted to our satisfaction. He was fully justified in his actions, as no one could stand such personal abuse from anyone. We want him reinstated for tomorrow’s game, May 18 or there will be no game. If players cannot have protection we must protect ourselves.9

President Johnson did not receive the telegram until he arrived at 6:40pm. in Albany, New York, where he was en route from the dedication of Fenway Park in Boston to the dedication of Crosley Field in Cincinnati. Johnson informed the press that he had wired Jennings and asked him to provide his version of the New York episode. He did not lift Cobb’s suspension. Johnson responded to the players’ threat to strike:

I am amazed at the attitude of player Cobb and his teammates toward the American League, which while insistent on good order on the field and strict compliance with the rules of the game, has always extended consideration and provided protection for its players. Suspended on report of the umpire. Suspend order not to remain in force indefinitely but until investigation is completed. Any American League player who is taunted or abused by a patron has only to appeal to the umpire for protection.10

Johnson also informed Jennings and Detroit owner Frank Navin that if the Tigers did not put a team on the field on May 18 they would be fined $5,000. Navin immediately put it on Jennings’s shoulders to field a team—any team—to avoid the fine. Jennings backed his striking players, issuing the statement: “The suspension was not warranted. I am in the hands of my players, if they refuse to play I will finish way down in the races. I expect Johnson to reconcile the matter, fine Cobb or announce definitely the length of the suspension.”11

Connie Mack, esteemed manager and owner of the Philadelphia Athletics, met with Jennings and encouraged him to gather some local sandlot ballplayers in case the Tigers regulars carried out their threat not to take the field. Mr. Mack did not care to lose the income from a Saturday crowd, and besides, the A’s likely would get an easy victory against players of lesser ability. Mack also mentioned that during the preseason the Athletics had played an exhibition game versus last year’s Philadelphia scholastic champs, St. Joseph’s College (and had lost the game to the collegians, 8-7).12 Jennings possibly could convince the college team to take the field in place of the Detroit regulars? Connie put Jennings in touch with a Philadelphia sports reporter, Joe Nolan, who was familiar with the St. Joseph’s team.13

Al Travers, an assistant student manager of the St. Joseph’s team who provided team statistics to Nolan, met with him the next morning. Nolan explained why the Detroit management wanted a backup team and said the sandlotters would be paid for their efforts. Travers said he would see what he could do.14 But the St. Joseph’s team had played the day before in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, against Conway Hall and apparently declined the offer.15 Travers then strolled to a popular Philadelphia City street corner and recruited several volunteers for the endeavor. (In several inter views in his later years Travers told the story about Nolan and going to the street corner to recruit players, but he apparently never identified any of the men he recruited).

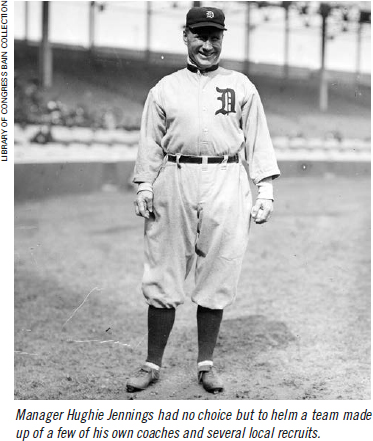

In the meantime, Jennings pressed two of his coaches/scouts into duty, Deacon Jim McGuire and Joe Sugden.16 Both were former major league players, but well past their baseball prime.

Cobb and his fellow players took the field before the game on May 18 but umpire Ed “Bull” Perrine waved Cobb off the grounds and the Tigers players followed.17 The Detroit regulars left their uniforms in the locker room and proceeded to the grandstand to watch the game. The strike was on.18 Jennings’s “misfits” donned the Detroit uniforms and took to the field to warm up. Allan Travers designated himself the pitcher after Jennings told him the pitcher would get $25 while the rest would have to be satisfied with $10 each. As we will discuss, some accounts of the affair have Travers getting $50 and the others, $25.

Umpires Perrine and Dinneen yelled “Play Ball” and the unlikely contest was underway. About 15,000 fans applauded as “Colby Jack” Coombs, a veteran Athletics hurler, took the mound. Coombs had last pitched on May 14 against the Chicago White Sox after being side lined for a groin injury he had incurred on April 20 in Washington. Mack had implied to Jennings that he would play his reserves against the Tigers’ make-do team, but when the Athletics took the field, only two substitutes were in play, Harl Maggert and Amos Strunk.19

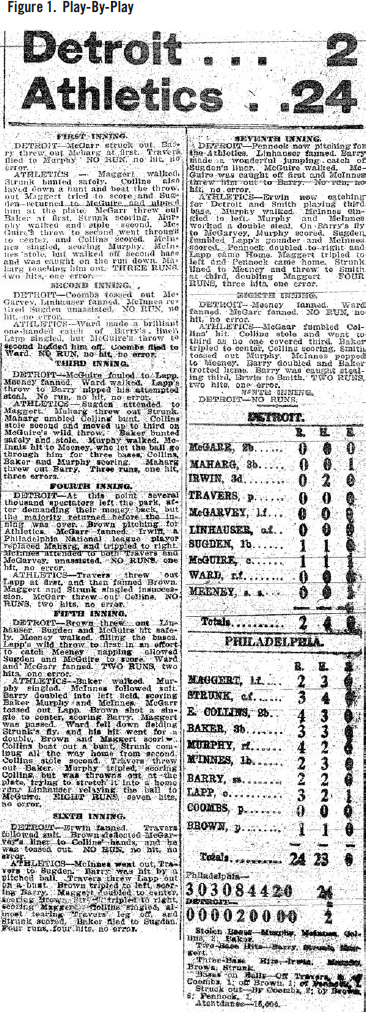

The play-by-play reproduced in Figure 1 is from the Detroit Times, but note that it is missing the details of the ninth inning.20 The following is derived from the box scores of the day:

NINTH INNING

DETROIT: Irwin tripled. Hughie Jennings bat ted for Travers and struck out. McGarvey was hit by a pitch. McGarvey stole second. Leinhauser fanned. Sugden struck out to end the game. No runs, no hits, no errors.21

The contest lasted 1 hour and 45 minutes. Colby Jack Coombs was declared the winner.

The Tigers regulars bought tickets and watched the fiasco from the grandstand. Donie Bush, Detroit shortstop said, “It’s a circus. Gosh, I’m glad I came.” Jim Delahanty, one of the instigators of the strike, stated, “This is great, I wouldn’t have missed it for a minute.”22 Although a second sacker of credible ability, Delahanty was released by the Tigers in August and was not offered a contract by any other club. One of five major-league brothers out of Cleveland, Ohio, Delahanty, with the exception of a two-year stint in the Federal League with Brooklyn (1914-15), would never again play major-league ball. Some say it was retribution for his role in the strike.23

Jennings washed his hands of the whole matter. “I put a team on the field today to save the owners of the Detroit franchise from being fined $5,000. It is now up to President Johnson of the league and President Navin of the Detroit club to settle with the ‘strikers.’ I do not intend to take sides one way or the other. You can say this much for me. There will be a club, professional club of some sort on the field at Shibe Park on Monday.”24

Due to Pennsylvania Blue Laws, no professional games were played on Sundays. American League President Ban Johnson arrived at the Bellevue-Stratford Hotel in Philadelphia on Sunday May 19 and declared there would be no game on Monday and that the Tigers would not play again until the regular team was placed on the field. On Monday, Johnson, Ben Shibe (president of the Athletics), and managers Mack and Jennings met at the hotel as they waited for Navin to arrive from Detroit. Johnson remarked that Jennings apparently forgot he was a representative of the owners and not the players.25

Back at the Aldine Hotel the Detroit regulars were apprehensive about their strike position but Delahanty insisted the players were still sticking together. Chair man Delahanty of the “insurgents” was busy sounding out his teammates and players of other clubs as to the formation of a players’ union.26

At 3:35pm on May 20, Navin announced that he had reached an agreement with his striking players. Navin stated that the team would take the field in Washington without the services of Cobb, who would be suspended pending the investigation of his actions in New York, and that he, Navin, would take care of all fines inflicted upon the players for the strike.27

Cobb spoke to the players after Navin pleaded with them to return to the field:

My advice to you is to stick by Mr. Navin, who is one of the best friends we all have. I can’t tell you how much I appreciate the way you have backed me up and stuck by me—and I know you would go through to the finish with it—but I don’t want to take the responsibility of having all you good fellows fined and blacklisted and all that. So I hope if you can see your way clear you all will get back into the game and play for Mr. Navin—and win. I’ll be with you soon, I hope.28

Cobb arrived in Washington on May 21 and issued the following statement to the press:

It matters little to me when president Johnson lifts my suspension. I have made up my mind to go home tonight, no matter whether or not the suspension is lifted or not. If Johnson should decide to lay me off for a month or the remainder of the year, I will be perfectly satisfied. My action in New York was simply on a principle and the Detroit Club will be the sufferer, as my pay goes on, no matter whether I play or not. The same applies to any fine that may be assessed against me, so that if Johnson is seeking to punish me, he will find a different proposition.29

On that same day Ban Johnson announced that he had fined 18 of the Detroit strikers $100 each, representing $50 for each game they missed during the walk-out. Johnson further said he would deal as lightly as possible with Cobb considering the circumstances.30 Those fined were: Sam Crawford, L.E. McCarthy (business manager), Donie Bush, Oscar Vitt, Davy Jones, Jim Delahanty, Oscar Stanage, Jean Dubuc, George Moriarty, R.E. Willet, H.H. Purnoll, Bill Burns, George Mullin, J. Onslow, B. Kocher, H. Perry, Ralph Works, and T. Covington.

In the evening hours of May 25 Johnson officially lifted Cobb’s suspension and fined the Detroit star $50. Johnson stated, “Cobb did not seek redress by an appeal to the umpire, but took the law into his own hands. His language and conduct were highly censurable.”31 Johnson also promised future full protection from spectator abuse to all players and that the league had taken steps to increase police authority on all American League grounds.

Cobb was not fined for missing any games as he was under suspension during the strike.

Claude Luecker, the erstwhile victim in the affair, was described as an innocent looking gentleman “with a jovial face and merry eyes” who was determined to sue Cobb for heavy damages.32 It is not known if Luecker ever followed through with any legal action against Cobb. However, it was later reported that Luecker had run-ins with Cobb years before the infamous incident and at that time Claude was a well-conditioned athlete who had not yet suffered the damage to his hands. Supposedly, this is why Luecker razzed Cobb and when Cobb recognized his old enemy, he went after him.33 Little is known about Luecker’s life after the episode. The time and place of his death is unknown.

We know a bit more about the men who took the field in place of the Tigers, although some mysteries about them persist.

The most interesting controversy is the shortstop position. According to Baseball Encyclopedia folklore, Bill Leinhauser was asked in the late 1950s to research and verify the names of his teammates of that day. Using his memory and the box score of the game, Leinhauser puts Pat Meaney at shortstop, and that is how it was noted in The Baseball Encyclopedia for many years. However, in the early 2000s, Bill Dougherty—a SABR member and a Batavia, New York, baseball historian—made the claim that one Edward Vincent Maney, also of Batavia, was the actual Tigers shortstop.

Dougherty’s evidence included Maney’s obituary of March 12, 1952, which mentions that he was a participant of that game. In a letter to his brother, Maney wrote, “I played shortstop and had more fun that day then you can imagine. Of course, it was a big defeat for us, but they paid us $15 for a couple of hours work and I was satisfied to say I played against the World Champions. I had three putouts, one error, and no hits.” The player in the game did have three putouts and one error, however, the letter neglects to say that he walked or was hit by a pitch and that an error by the Philadelphia catcher attempting to pick him off first base resulted in the Tigers’ only two runs of the game. Dougherty also provided a picture of someone in a Tigers uniform, standing next to Detroit manager Hughie Jennings on the day of the game. The grainy black and white photograph could be Maney, but due to its poor quality it is difficult to tell.

Dougherty also noted that Pat Meaney threw left handed and that Edward Vincent Maney threw from the right side; shortstops are almost never southpaws. But many writeups of his day note that Pat Meaney was proficiently ambidextrous. Finally, there is a newspaper article in the May 23, 1912, edition of the Batavia Daily News stating that Batavian S. Vincent Maney played shortstop for the Detroit Tigers on May 18, 1912. The article notes that he was the office manager of the Iroquois Iron Works in Philadelphia. The Iroquois Iron Works was headquartered in Buffalo, near Batavia, and may have had an office in Philadelphia in 1912. There is a Vincent Maney in the 1912 Philadelphia City directory listed as a bookkeeper.

I believe that Pat Meaney, having been identified by Bill Leinhauser as his teammate, having been a friend of Tigers first baseman Joe Sugden, and having thrown from both the left and right side for many sea sons, was the shortstop on that day in Philadelphia. Mr. Vincent Maney may have been a recruit who sat the bench, but I do not think he played shortstop that day. Ironically, in the 1880 Federal Census the Patrick Meaney family name is spelled “Maney.”

To further muddy the shortstop waters, a well-known Philadelphia semi-professional shortstop by the name of Joe Harrigan is also mentioned by one newspaper of the day as having been at short, but the box score in the same paper has Meaney in the lineup and not Harrigan. Maybe Harrigan was another recruit who did not get in the game.34

As mentioned previously there are conflicting reports about how much each player was paid—anywhere from $10 to $50 according to newspaper accounts, Mr. Maney’s letter, and Father Al Travers’s interview. Would not the contracts the players signed that day state the amount of pay? Unfortunately, in 1912 major league teams only had to sign players to contracts after they had been on the club for five days. Here are the players:

James Vincent “Jim” “Red” McGarr, 23, a machinist in a locomotive factory, handled second base adequately, making only one error in four chances. “Red” possibly received his nickname from his red hair or the fact he lived on Redner Street in Philadelphia. By 1917 McGarr was employed as a Philadelphia firefighter. He served in the United States Army in WWI and was treated for shrapnel wounds and shell shock. Later in life, McGarr left the Philadelphia Fire Department and opened a cafe. He moved to Fort Lauderdale from Philadelphia in 1947 and died at Veterans Hospital in Miami, Florida, on July 21, 1981, the last surviving member of the “misfits” of May 18, 1912.

William Joseph “Billy” Maharg, 31, a farmhand and auto mechanic, took the field at third base. At only 5-foot-4-inches, Maharg boxed professionally and fairly successfully, 45-11 with 18 no-decisions 1900-07.35 A featherweight pugilist, Billy was well-known for his aggressive style. Often a headliner in the Philadelphia, Lancaster, and York, Pennsylvania area, Maharg was a fan favorite whose real name was thought to be “Graham”—Maharg spelled backwards36—but that proved to be false.37 Billy worked on the family farm in Fox Chase, Pennsylvania, but also hung around the Philadelphia sports scene, serving as a gofer and chauffeur for pitcher Grover Cleveland Alexander and other Phillies. Maharg was suggested to Jennings as a replacement player for the May 18, 1912, game by Detroit pitcher “Sleepy” Bill Burns, who had become an acquaintance of Maharg’s while hurling for the Phillies the previous season.38 On the last day of the 1916 major league season Maharg, then officially the Phillies assistant trainer, made his second and last major league playing appearance, pinch-hitting in the eighth inning, grounding out, and spending the ninth stanza patrolling right field without a fielding opportunity.

During WWI Billy found work as a driller for the Baldwin Locomotive Works, possibly the same place former teammate Jim McGarr worked. However, Maharg was not through with major league baseball. In 1920 Billy spilled the beans to a Philadelphia reporter that he, his friend Burns, and ex-featherweight prizefighter Abe Attell had conspired with the notorious gambler Arnold Rothstein to bribe Chicago White Sox players to fix the 1919 World Series. Maharg received immunity for his testimony.39 Maharg eventually went to work for the Ford Motor Company in Chester, Pennsylvania, and he died in Philadelphia on November 20, 1953.

William Edwin Irwin, 34, a journeyman minor league player, was a bullpen catcher for the neighboring Phillies.40 Ed—or Bill, as he was commonly known—would replace Maharg at third base in the fourth inning and switch to catching in the seventh. Under tragic circumstances, he was the first of the Detroit misfits to pass away. On February 5, 1916, Irwin went to a local saloon with a friend and became involved in a barroom brawl. As reported in the Philadelphia Evening Ledger, things went badly:

Philly players will be shocked to learn of the death of “Bill” Irwin the young catcher who was taken south with the Phillies last spring. Irwin also helped both Doolin and Moran when they were short-handed by warming up pitchers and doing general utility work about the ball park. Irwin was thrown through the window of an uptown saloon; his jugular vein being sev ered. It was reported that the dead man’s first name was Edward, but it was in reality the Philly recruit.41

At the time of his death, Irwin was working as a special officer for the Pennsylvania Railroad. In those days railroads often hired competent ballplayers to play on the company ball teams. Irwin may have known Billy Maharg, since they both worked for the Phillies organization, and that could be how he was chosen to be a Tiger misfit.

Aloysius Stephen (Stanislaus) Travers, 20, a junior at St. Joseph’s College. would take to the mound for the replacements and toss mostly slow curveballs to the Athletics.42 Al pitched eight innings for the “paper Tigers” and gave up 24 runs on 26 hits. Aloysius was ordained a Catholic priest in 1926 and served at the Saint Andrew Novitiate in Hyde Park, New York, Saint Francis Xavier High School in Manhattan, and eventually at his alma mater, Saint Joseph’s College in Philadelphia. Later he taught at Saint Joseph’s Preparatory School in Philadelphia. Father Travers never cared to speak much about his day as a major league twirler. In 1955 he broke his silence and told his story in an interview with sportswriter Red Smith.43 Reverend Travers died in Philadelphia on April 19, 1968.

Daniel John McGarvey, 24, a chauffeur, positioned him self in left field for the replacements. McGarvey served in WWI and later worked as a civilian machinist in the Philadelphia Navy Shipyard. From 1927 until 1945 he spent time on and off in United States Veterans Institutions for disabled or mentally incompetent veterans. McGarvey died on August 18, 1945, in Kecoughton, Virginia.

William Charles Leinhauser, 18, an auto machinist, patrolled center field for the substitutes. Bill became a Philadelphia policeman in 1917 and rose to the rank of lieutenant in charge of the Narcotics Bureau. Leinhauser served in the Pennsylvania National Guard for three years before serving in France in WWI. In 1953 he was briefly suspended by the Philadelphia Police Commissioner for negligent duty but was later acquit ted by a police trial board.44 He retired from the Philadelphia Police Force in 1959. It was Leinhauser who, in the mid-1950s worked with co-author S.C. Thompson of The Official Encyclopedia of Baseball to track down the full names and birth data of the Detroit “misfits.” Leinhauser was proud to have worn Cobb’s uniform during the game.45 Bill Leinhauser died in Elkins Park, Pennsylvania, on April 14, 1978.

Joseph Sugden, age 41—Detroit Tigers coach and scout at the time of the game—came out of retirement to play first base for the misfits. Sugden was a major league catcher/first baseman for five teams between 1893 and 1905. In his youth, Sugden played sandlot baseball around the Philadelphia and Camden, New Jersey, area and began playing professionally for the Charleston Sea Gulls of the South Atlantic League in 1892. A catcher by trade and a life-long switch-hitter, Joe signed on with the Pittsburgh Pirates of the National League in 1893. Catching was a hazardous occupation in those days; protection was limited to crude face masks, thin gloves, light chest protectors and no shin guards. The Pirates carried four catchers on the roster, including the future Philadelphia Athletics owner/manager, Connie Mack.

The St. Louis Browns acquired Sugden in 1898 and then transferred him to the Cleveland Spiders the fol lowing year, in which the Spiders finished last in the National League with a 20-134 won-loss record. In 1900 Joe caught on with the American League White Stockings and the team took first place with Sugden catching most of the games. The American League was not considered a major league until 1901 and the White Stockings won the American League pennant that season, although Sugden was relegated to a backup role. Despite his increasing baseball age, Joe spent the next four years as mostly the starting back stop with the St. Louis Browns. In his last year with the Brownies, 1905, Joe met a fellow catcher Branch Rickey, a relationship that would prove fortuitous as Rickey would later hire Joe as a scout/coach. With his batting skills eroding, Joe spent 1906 and 1907 in the minor leagues with St. Paul. Not willing to give up the game he spent the next three seasons with the Vancouver Beavers of the Northwestern League.

In the spring of 1911, Jennings asked Sugden to go south with the team and coach his young pitchers. When the team went north, Sugden left to manage and play for the New Castle Nocks of the Ohio-Pennsylvania League. It would be the last time Sugden appeared in a regular season professional game until his appearance with the Detroit misfits of 1912. Sugden, although well past his prime, had kept himself in playing shape, occasionally covering first base for the Tigers as the team barnstormed its way north during the 1912 spring training season.46 While the Tigers were in spring training at Monroe, Louisiana, Sugden’s wife died suddenly back in their home in Philadelphia. When informed of her sudden illness, Joe left camp to be at his wife’s side but did not make it in time. Agnes Sugden died on March 4; Sugden returned to the Tigers on March 27. During WWI Sugden applied for a passport to travel to France to work with the YMCA in aiding the American Expeditionary Force. It is not known if Sugden followed through with that endeavor. After the misfit game, Joe continued to scout and coach with the Tigers, St. Louis Cardinals, and Philadelphia Phillies until his death in Philadelphia on June 26, 1959.

James Thomas “Deacon” McGuire, 48, a 26-year veteran of the major leagues, donned the “tools of ignorance” one more time for the Tigers replacement team. Deacon had earned his sobriquet for his gentlemanly manner and sportsmanship during his lengthy base ball career. As a professional ballplayer from 1883 to 1910, Deacon had rarely been thrown out of a game or fined.47 But on July 21, 1910, he was tossed from a game while managing Cleveland for arguing too ardently for a balk call against a Washington Nationals pitcher. The umpire who sent Deacon back to the team hotel? “Bull” Perrine, who was the infield arbiter in the “paper Tigers” game. McGuire began his big league career with the Toledo club in the American Association in 1884 and ended it 28 years later playing in the Tigers strike game. He participated behind the plate for an unfathomable 26 seasons, spending time with Toledo, Detroit (NL), Philadelphia (NL), Cleveland (AA), Rochester (AA), Washington (AA), Washington (NL), Brooklyn (NL), New York (AL), Detroit (AL), Boston (AL), and Cleveland (AL). Deacon managed the Washington Senators (1898), Boston Red Sox (1907-08), and the Cleveland Naps (1909-11). In 1912 he signed on as a Tigers coach/scout as a favor to his former Brooklyn teammate, Tigers manager Hughie Jennings. McGuire retired in 1926 to his farm in Deer Lake, Michigan, where he died of bronchopneumonia on October 31, 1936. Deacon died on Halloween, which seems appropriate since he wore a mask at work for 26 years.48

Patrick A. Meaney, 40, performed at shortstop for the replacement Tigers. A long-time (1892-1909) minor leaguer who started his career as a left-handed pitcher of great promise, was a friend of Joe Sugden when they played together in Camden. Sugden may have recruited Pat for the game. Meaney resided at 2231 Redner Street just a few houses from teammate Jim McGarr. Possibly Meaney recruited McGarr, or vice versa. Meaney was hurling for the Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, team when his arm went dead. Always a strong hitter, Meaney learned to throw righty, moved to right field and ex celled. In 1902 he jumped to a team in San Francisco where he continued to throw from the right side. It was well-publicized that Meaney was an ambidextrous thrower, as in this newspaper account:

An interesting story on a former coal region player comes from California. Pat Meaney who used to be the right field star for Harrisburg when the latter was in the State League went to the coast last fall and is now playing the out field for San Francisco. Pat used to be a southpaw twirler until his arm went “dead” and he then learned to throw with his right wing and starred in the outfield. He used to perform regularly with his right hand last season….Hurt his shoulder and went back to his left.50

A professional and sandlot baseball player his entire life, Meaney died in Philadelphia on October 20, 1922, of a brain tumor. At the time of his death his occupation was listed as “ballplayer.”

John Joseph Coffey a.k.a. Jack Smith, 18, one of the youngest of the misfits, entered the game as the Tigers third baseman in the seventh inning, with Irwin moving from third to behind the plate, relieving McGuire. Jack had worked as an office boy prior to his incarceration for larceny in the Pennsylvania Industrial Reform School in Huntingdon, Pennsylvania, on March, 16, 1912. His troubles with the law may explain the name subterfuge; maybe he was not where he should have been that day. Coffey was residing with his employer when he was arrested for larceny and receiving stolen goods. His sentence was three years at the Pennsylvania Industrial Reformatory in Huntingdon, so he was either paroled or escaped prior to joining the “paper Tigers.” Two months after the game (July 13) he was alleged by Philadelphia police to have sold a large number of newspapers under false pretenses by shouting falsely that Colonel Roosevelt had been assassinated and his murderer hanged.51 Coffey also spent time in the county jail during WWI. Later in life he worked in New York as a writer for a publishing company and as an insurance agent. He died in New York City on December 4, 1962.

Joseph Nichols Ward, 26, worked as a salesman and covered right field for the strikebreakers, making the catch of the game in the third inning. Although Ward is often given the nickname “Hap” in current biographies, there is no mention of that moniker in any write-ups of the day. A “Hap” Ward was a very popular vaudeville entertainer at that time so it is possible that is where the confusion is derived. Ward was a well-known sandlot player in the New Jersey and Philadelphia area. He worked as a salesman for Duo fold Inc., an undergarment company, mostly out of Camden. Joseph claimed an exemption from the WWI draft due to being the sole provider of his mother and wife. However, in June 1918 he traveled to France and later Italy and worked for the YMCA. The YMCA supplied thousands of paid staff and volunteers to provide spiritual, mental, and physical “welfare” services to the doughboys. Ward returned from Europe in February 1919. Joseph died in Elmer, New Jersey, on September 13, 1979.

Hugh (Hughie) Ambrose Jennings, 43, the manager of both the real and “paper” Tigers, pinch-hit and struck out for Travers in the ninth inning. He began his big league career in 1891 with the Louisville Colonels and was the shortstop on the great Baltimore Orioles teams of the mid-late 1890s. In 1899 he moved on to the Brooklyn Superbas who won the National League pennant that year and the next. After a stint with the Philadelphia Phillies, he returned to Brooklyn in 1903. In 1907 Hughie was hired as manager of the Detroit Tigers and led them to the American League pennant three consecutive years (1907-09). Although he never managed another pennant-winner, he led the Tigers until 1921. In the offseason, Jennings attended Cornell Law School and eventually practiced law in the winter months. Upon leaving the Tigers he coached for the New York Giants (1921-25). After the 1925 season, Jennings retired to Scranton, Pennsylvania, where he died of tubercular meningitis on February 1, 1928. He was elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown in 1945.52

Other players who may have been in the dugout but not on the field were Arthur “Bugs” Baer53 and the aforementioned Vincent Maney and Joe Harrigan.54 Contrary to the reports of the day and subsequent ones, the substitutes were not baseball collegians; only Travers attended college at the time, and he was not on his college team. McGarvey and McGarr were reported to be former Georgetown college players, but that appears unlikely, as neither finished high school.

It is interesting to note that the game against the paper Tigers did not turn into a farce until the bottom of the fifth. After four and a half innings the score stood 6-2. The eight-run fifth inning did in the make-believe major leaguers. Their errors didn’t help, but they made two spectacular plays in the outfield, hit the ball on occasion, had the game’s only double play, and fielded twenty-four outs. Not bad for a pitcher who could not make his college team, a pint-sized pugilist, two base ball elder statesmen, a journeyman bullpen catcher, a former minor league star pitcher turned shortstop, a salesman, and a few mechanics, and a chauffeur.

KEVIN W. BARWIN is a retired Northwest Regional Audit Supervisor with the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania with a BA degree from the University of Pittsburgh and a MBA degree from Clarion University. He has contributed to the SABR Biography Project and has written several baseball related articles contained in his book The Paperboy From the Paper City. Kevin can be reached at kbdb5417@yahoo.com. He resides among his library of over a thousand baseball books in Erie, Pennsylvania.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Ancestry.com and Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1. “Cobb Turns to Boxing,” New York Tribune, May 16, 1912, 10.

2. “Ty Would Thrash Again,” The Sun (New York, New York), May 17, 10.

3. “No Sign of Break in Baseball Strike,” The Lincoln Star, Lincoln, Nebraska, May 19, 1912, 7.

4. “Big Baseball War May Follow Tigers’ Strike to Aid Cobb,” The Evening World, New York, NY, May 18, 1912, 1-2.

5. “Cobb Thrashes Fan,” Washington Post, May 16, 1912, 7.

6. “Ban Johnson Sees Fight From Stands,” Washington Post, May 16, 1912, 7.

7. “Ty Cobb Suspended,” The New York Times, May 17, 1912, 11.

8. “Cobb Banished From Game,” New York Tribune, May 17, 1912, 10.

9. “Tigers Ultimatum to Pres Johnson,” Boston Globe, May 18, 1912, 1.

10. “Suspension Stands,” Boston Globe, May 19, 1912, 9.

11. Boston Herald, May 18, 1912.

12. “Mackies Ease Up, St. Joseph’s Win,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 11, 1912, 10.

13. Gary Livacari, “Allan Travers,” SABR BioProject, accessed November 10, 2022.

14. Livacari, “Allan Travers,” SABR BioProject.

15. “St Joe Beats Conway Hall,” Philadelphia Inquirer, May 19, 1912, 10.

16. “Detroit Players Strike; Jennings Signs Amateurs,” Pottsville Republican (Pennsylvania), May 18, 1912, 1.

17. “Stir Up Over Ty Cobb,” Tuscaloosa News,” May 19, 1912, 1.

18. Some characterize the Tigers’ walkout as the first players strike in major-league history, but five Louisville players struck during the disastrous 1889 season of the Louisville Colonels in the American Association.

19. Commercial Tribune, (Cincinnati), May 19, 1912, 14.

20. “Detroit Players Make Their Threat Good And Walk Off Field,” Detroit Times, May 18, 1912.

21. The play-by-play found in the Detroit Times ends before the ninth inning. The preceding is derived from the box scores of the day.

22. “Detroit Team On Strike,” The New York Times, May 19, 1912, 1.

23. “Grave Story-Jim Delahanty,” RIPBaseball.com

24. “Quakertown Not Quiescent When Quasi Tigers And Champs Play,” Canton News Democrat, May 19, 1912, 12.

25. “Baseball Strike Growing Worse,” Plainfield Daily Press, May 20, 1912, 9.

26. “Johnson Calls Of Game With Detroit,” The New York Times, May 20, 1912, 2.

27. “Big Baseball Strike Is Over,” Winona Republican Herald, (Winona, MN), May 21, 1912, 2.

28. “Detroit Tigers Will Play Ball,” Bradford Era (Bradford, PA), May 21, 1912, 7.

29. “Ty Cobb Quits Tigers; Will Depart For Home,” St. Louis Star and Times, May 21, 1912, 13.

30. “Players Fined $100 Each,” Daily News (Frederick, MD), May 22, 1912, 7.

31. “Tyrus Cobb Is Reinstated And Is Fined But $50,” Washington Herald (District of Columbia), May 26, 1912, 39.

32. “Victim Will Sue Cobb,” The New York Times, 32 May 20, 1912, 2.

33. “Sporting Briefs,” Nashville Banner, March 3, 1913, 10.

34. “Suspension Stands,” Boston Herald, May 19, 1912, 1.

35. Bill Lamb, “Billy Maharg,” SABR BioProject, accessed November 10, 2022.

36. “Weekly Review of Sports,” Intelligencer Journal (Lancaster), November 14, 1908, 8.

37. Lamb, ”Billy Maharg,” SABR BioProject.

38. “Detroit Team on Strike,” The New York Times, May 19, 1912, 1.

39. Lamb, “Billy Maharg,” SABR BioProject.

40. Bill Lamb, “Ed Irwin,” SABR BioProject, accessed November 10, 2022.

41. “Seaton’s Arm Is As Good As Ever, Philadelphia Evening Public Ledger, February 9, 1916, 12.

42. “Strikebreakers Have No Chance,” Omaha Bee, May 19, 1912, 37.

43. “Allan Travers,” SABR BioProject.

44. “Phil. Objects to Dope Smear,” The Plain Speaker (Hazelton, PA), October 23, 1953, 2.

45. The Official Encyclopedia of Baseball, Revised Edition 1959, 522.

46. “First Game Of The Season Went To Tigers 9-2,” Hattiesburg Daily News, March 27, 1912, 8.

47. “Is A Model Deacon,” Anaconda Standard (Anaconda, Montana), April 24, 1910, 24.

48. Robert W. Bigelow, “Deacon McGuire,” SABR BioProject, accessed online November 10, 2022.

49. “A Club Without A Home,” Philadelphia Inquirer, March 28, 1895, 6.

50. “Base Ball,” The Plain Speaker (Hazelton, Pennsylvania), August 13, 1903, 1.

51. “Fake News Caller Fined,” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 13, 1912, 5. Ironically, Roosevelt was shot in an assassination attempt in Milwaukee, Wisconsin on October 12, 1912.

52. C. Paul Rogers III, “Hughie Jennings,” SABR BioProject, accessed November 10, 2022.

53. Philadelphia Inquirer, May 19, 1912, 15.

54. “Detroit Team Out on Strike,” The New York Times, May 19, 1912, 1.