Pitchers in the Field: The Use of Pitchers at Other Positions in the Major Leagues, 1969–2009

This article was written by Philippe Cousineau

This article was published in Fall 2011 Baseball Research Journal

INTRODUCTION

Pitchers are a breed apart. On average, they are taller and heavier than most players; contrary to their fielding brethren, they do not play every day; even the most resilient of relievers have to sit out half of their team’s games or risk burning out their arms, and most starters will work only every fifth day. In most leagues, including in college and the minor leagues below AA, pitchers never come to bat. But the most striking distinction is that pitchers almost never play another position in the field. This article will look at the few exceptions when this rule was broken in major league games since the advent of the divisional era in 1969, in order to establish patterns and trends of what is an exceedingly rare event: a pitcher occupying a fielding position other than the mound.

It is important to note at the outset that I am looking at full-time pitchers playing the field, and not its mirror event, the “joke pitcher” or “mystery pitcher,” in which a regular fielder is used as a pitcher in a blow-out or other special circumstances. Nor am I looking at permanent conversions from fielding to pitching (something which is relatively common, especially in the minor leagues)—or vice versa (a much rarer occurrence, with Rick Ankiel being a recent case).

Supplemental material: View a complete list of MLB pitchers from 1969 to 2010 who have made an appearance at another position in the field

There is also the one exceptional two-way player during the period, Brooks Kieschnick,[fn]Kieschnick was a two-way player at the University of Texas who became a full-time outfielder after being drafted in 1993. He played intermittently in the majors 1996–2001. With his career foundering in 2002, he began to pitch part-time in the minor leagues, and made the Milwaukee Brewers’ roster as a pitcher/pinch hitter in 2003, playing very well in both roles, logging 42 games on the mound, 3 in the outfield and 4 at DH. He also played for the Brewers in 2004, exclusively as a pitcher or pinch-hitter, before washing out of organized baseball.[/fn] who is outside the scope of this study. Also ignored are instances where a pitcher is listed in the starting line-up at a random position, but is replaced before taking the field on defense.[fn]Pitcher Gene Garber was listed in the starting line-up on July 4, 1978 as the Atlanta Braves’ center fielder, but was replaced by pinch-hitter Rowland Office in the top of the first inning.[/fn] This paper will focus exclusively on pitchers who, for some reason, found themselves one day playing the outfield or the infield in a major league game.

A SEPARATION OF ROLES

In modern Major League Baseball, the separation of roles between the pitcher and other fielders is quite strict. They are two different breeds of athletes. They train differently, are paid on different scales, and never the twain shall meet. Yet in Little League, high school, and college ball, the separation is not so strict: the best athletes are normally used as pitchers, and these are also the top sluggers. They will sometimes play the more demanding positions, such as shortstop or center field, when not on the mound. However, because pitchers are often very tall, or left-handed, it may limit their ability to play certain positions, so they will gravitate towards the role of first baseman or designated hitter when not pitching.

It is not rare for college players to excel in both roles, including in top Division I schools in the NCAA. Every year in the first year player draft, a player is selected in the first round for whom there is a question whether he will play professionally as a hitter or a pitcher; never is there a possibility of him doing both, except at the lowest levels of the minor leagues. Among such recent two-way athletes coming out of college were John Olerud,[fn]Olerud was so good in both roles while in college that the NCAA recently named an award for two-way players in his honor.[/fn] Marquis Grissom, John Van Benschoten,[fn]Van Benschoten led all Division I players in home runs his senior year at Kent State University in 2001 while being an indifferent pitcher. Yet for some reason the Pittsburgh Pirates, who drafted him in the first round that year, decided to make him strictly a pitcher. His career has been a complete bust.[/fn] Micah Owings, and many others. Yet, as soon as they hit the professional ranks, the segregation begins. Bill James explained that this is a result of the extremely high caliber of today’s game: only the very best can cut it in the major leagues, and players can maintain only one set of skills at such an elite level. Because pitching and hitting are such different practices, it is almost impossible for ballplayers to excel at both, and they must specialize. When the quality of play in the major leagues was lower, such extreme segregation did not exist: in the 19th century, many pitchers were capable hitters as well. Almost every regular pitcher logged some games at one or more other positions, and it was common for a fielder to take a turn pitching from time to time.[fn]Bill James: “The Time Line,” in Whatever Happened to the Hall of Fame?, (New York: Fireside Books, Simon and Schuster, 1995), 230–242.[/fn] This continued into the late 1940s, although crossovers became increasingly rare with each decade. By 1960, the situation that prevails today was solidly entrenched.

It is not rare for college players to excel in both roles, including in top Division I schools in the NCAA. Every year in the first year player draft, a player is selected in the first round for whom there is a question whether he will play professionally as a hitter or a pitcher; never is there a possibility of him doing both, except at the lowest levels of the minor leagues. Among such recent two-way athletes coming out of college were John Olerud,[fn]Olerud was so good in both roles while in college that the NCAA recently named an award for two-way players in his honor.[/fn] Marquis Grissom, John Van Benschoten,[fn]Van Benschoten led all Division I players in home runs his senior year at Kent State University in 2001 while being an indifferent pitcher. Yet for some reason the Pittsburgh Pirates, who drafted him in the first round that year, decided to make him strictly a pitcher. His career has been a complete bust.[/fn] Micah Owings, and many others. Yet, as soon as they hit the professional ranks, the segregation begins. Bill James explained that this is a result of the extremely high caliber of today’s game: only the very best can cut it in the major leagues, and players can maintain only one set of skills at such an elite level. Because pitching and hitting are such different practices, it is almost impossible for ballplayers to excel at both, and they must specialize. When the quality of play in the major leagues was lower, such extreme segregation did not exist: in the 19th century, many pitchers were capable hitters as well. Almost every regular pitcher logged some games at one or more other positions, and it was common for a fielder to take a turn pitching from time to time.[fn]Bill James: “The Time Line,” in Whatever Happened to the Hall of Fame?, (New York: Fireside Books, Simon and Schuster, 1995), 230–242.[/fn] This continued into the late 1940s, although crossovers became increasingly rare with each decade. By 1960, the situation that prevails today was solidly entrenched.

So, how impenetrable is the barrier between the mound and the rest of the playing field? Let’s put it this way. As a spectator at a random major league game, you are almost twice as likely to see a no-hitter than to see a pitcher take the field: there were 96 sanctioned no-hitters during the period, but only 54 instances of a pitcher taking the field. Witnessing a triple play or a batter hitting for the cycle is a much more likely event—there were 35 triple plays turned between 2000 and 2009 alone! And fielders taking the mound are nowhere near as rare as the obverse—there were over 179 occurrences during the same period. It has thus become one of the rarest events that can happen in a Major League Baseball game. So when this albino raven is sighted, what causes it?

THREE TYPES OF CIRCUMSTANCES

There are three usual circumstances in which a manager will decide to use a pitcher in a position normally reserved for a fielder: running out of fielders, as a special strategy to bring a pitcher back into a game, or to indulge a player. The few cases that fall outside of this pattern will be discussed later.

a) Running out of players. From Opening Day to September 1, major league teams are limited to a roster of 25 players.[fn]For limited periods in the late 1970s and 1980s, the roster limit was 24 and not 25; it was also 26 or 27 for other brief periods when spring training was shortened by labor strife.[/fn] This would seem to make plenty of substitutes available, given that only 9 or 10 players are in the game at the same time, depending on whether the designated hitter rule is in effect. But there are times when 15 or 16 substitutes are not enough. First, the typical roster includes anywhere from 10 to 13 pitchers, limiting the number of players available to act as defensive substitutes or pinch hitters. Second, not everyone is available to play every day, because of nagging injuries or temporary absences. Managers will make sure that they always have some options left on their bench, but sometimes circumstances can make their plans go awry. The most common of these are injuries—especially injuries to a substitute—or ejections. When these occur in an extra-inning game, after a number of substitutes have already been used, a manager can find himself in a situation in which the only option left is using one of his pitchers as a substitute. These are often highly memorable games, and we will mention a few cases below.

b) The Pitcher in the Outfield Strategy. In contrast to the first circumstance, these cases are the result of a deliberate strategy. In order to gain a platoon advantage, a manager will remove his pitcher to bring a reliever throwing with the other hand. So far, nothing unusual. But if the manager thinks that he will want to use the removed pitcher at a later point of the game, he can do so by inserting him in a fielding position, for example, left field. When the second pitcher has faced the batter or batters against whom he had the platoon advantage, the manager brings back the first pitcher from left field and has him return to the mound. It sounds simple enough, but in effect, it is an enormously complicated strategy to execute, with little upside and a lot of potential downside. First there must be a string of batters who bat from different sides—no switch-hitters—and who are unlikely to be pinch hit for. Second, the first pitcher must be able to field a

position passably. Given that most pitchers routinely shag flies during batting practice, they can be counted on to catch most routine fly balls, but can they be counted on to back up the fielder next to them, play a line drive off the wall, or throw to the right cut-off man? And let’s not even talk about complex positions such as the middle infield or catcher, which require very specific skills learned only through repetitive practice.[fn]In fact, no player in our study was used either at shortstop or catcher.[/fn] There is clearly a defensive cost to playing someone out of position. Next, if two pitchers are in the line-up at the same time, one of the regular fielders must come out of the game for good—is that more costly than the temporary gain in platoon advantage? And finally, how long can a pitcher stay at a position away from the mound before getting cold—he will not be allowed any warm-up tosses if he comes back to pitch during the inning.

Thus, in practice, it is a very difficult strategy to execute, and in the days of the seven- or eight-man bullpen that may include two or three left-handers, is it really worth the rigmarole? Apparently, it still is once in a while: in the 9th inning of a nationally-televised Sunday night game on July 12, 2009, Cubs manager Lou Piniella decided to send lefty Sean Marshall to left field, have righty Aaron Heilman retire one Cardinal batter in a tight spot, then return Marshall to the mound to finish the inning. The strategy worked, and Piniella’s opposite, Tony LaRussa, was quick to praise his opponent for a genius move. The strategy was actually marginally more common in the days of 10-man pitching staffs, and a few managers would have a pitcher they trusted to send to the field for a batter or two, most notably Frank Lucchesi with Dick Selma and Whitey Herzog with Todd Worrell,[fn]Herzog even used the strategy in Game 6 of the National League Championship Series, on October 13, 1987.[/fn] but even then it was a Rube Goldberg machine of a strategy: sometimes effective, but too complex for its own good.

c) Indulging a Favorite Son. It is perhaps surprising that in the rather conservative and cold-hearted world of Major League Baseball, managers will sometimes do silly things to indulge a favorite player’s wishes. There have been cases of managers letting a pitcher bat for himself and declining the use of the designated hitter for the day,[fn]For example, Ferguson Jenkins pitched and batted ninth for the Texas Rangers on October 2, 1974.[/fn] allowing a pitcher to pitch ambidextrously for an inning,[fn]Greg Harris, on September 28, 1995.[/fn] or letting a player play nine positions in one game.[fn]For example, Scott Sheldon and Shane Halter, both at the tail end of the 2000 season.[/fn] It has happened a number of times with pitchers getting a chance to play a fielding position. The common thread here is that this always takes place in the dying days of the season, in a game whose outcome has no bearing on the pennant race, and even then in circumstances that do not affect the game’s outcome. If you have once wondered why Randy Johnson—standing 6-foot-10 and rather awkward even while doing nothing—is credited with a game in the outfield, be it known that on October 3, 1993, Lou Piniella had him replace Brian Turang for an inning in left field. Rick Langford was the beneficiary of a similar largesse. A less frivolous instance was on September 30, 1984, when Chuck Tanner gave a start in left field to Don Robinson in the second game of a doubleheader. Robinson, who was a solid hitter, had been troubled by a series of arm injuries in the early part of his career and there was some thought of converting him into a full-time outfielder. In the end, he pitched in the majors until 1992, although he continued to be used occasionally as a pinch-hitter.

c) Indulging a Favorite Son. It is perhaps surprising that in the rather conservative and cold-hearted world of Major League Baseball, managers will sometimes do silly things to indulge a favorite player’s wishes. There have been cases of managers letting a pitcher bat for himself and declining the use of the designated hitter for the day,[fn]For example, Ferguson Jenkins pitched and batted ninth for the Texas Rangers on October 2, 1974.[/fn] allowing a pitcher to pitch ambidextrously for an inning,[fn]Greg Harris, on September 28, 1995.[/fn] or letting a player play nine positions in one game.[fn]For example, Scott Sheldon and Shane Halter, both at the tail end of the 2000 season.[/fn] It has happened a number of times with pitchers getting a chance to play a fielding position. The common thread here is that this always takes place in the dying days of the season, in a game whose outcome has no bearing on the pennant race, and even then in circumstances that do not affect the game’s outcome. If you have once wondered why Randy Johnson—standing 6-foot-10 and rather awkward even while doing nothing—is credited with a game in the outfield, be it known that on October 3, 1993, Lou Piniella had him replace Brian Turang for an inning in left field. Rick Langford was the beneficiary of a similar largesse. A less frivolous instance was on September 30, 1984, when Chuck Tanner gave a start in left field to Don Robinson in the second game of a doubleheader. Robinson, who was a solid hitter, had been troubled by a series of arm injuries in the early part of his career and there was some thought of converting him into a full-time outfielder. In the end, he pitched in the majors until 1992, although he continued to be used occasionally as a pinch-hitter.

SOME MEMORABLE GAMES

We have looked at some of the “run-of-the-mill” instances of a pitcher playing in the field, if there is such a thing. Let’s now look at the more bizarre ones.[fn]See the supplemental table on the SABR website to this article for full details.[/fn]

a) Is that an infielder which stands before me? On July 6, 1970, Cleveland Indians manager Alvin Dark pulled off the pitcher-to-the-outfield strategy with a twist. He sent huge left-hander Sam McDowell to second base while Dean Chance took the mound for a third of an inning. It must have made sense at the time, but the thought of McDowell playing the middle infield is puzzling. On September 2, Dark had McDowell play a more conventional first base while Chance relieved him temporarily, and on September 25, he had right-handed rookie Jim Rittwage go to third base for a spot while Rick Austin took the mound in the fourth inning. These are 3 of only 10 cases of a pitcher playing a position other than the outfield during the period.

b) Sometimes they do field. In the entire history of the Montreal Expos, from 1969 to 2004, only once did a pitcher take the field for either team. It happened on September 22, 1972, when shortstop Tim Foli was ejected from the game in the 10th inning. Steve Renko, who had been converted to pitching in the minor leagues, took over at first base as manager Gene Mauch re-jiggered his defense. Renko recorded five put-outs until the Expos lost the game in the 12th. This is the most fielding chances in one game by an out-of-position player during the period.

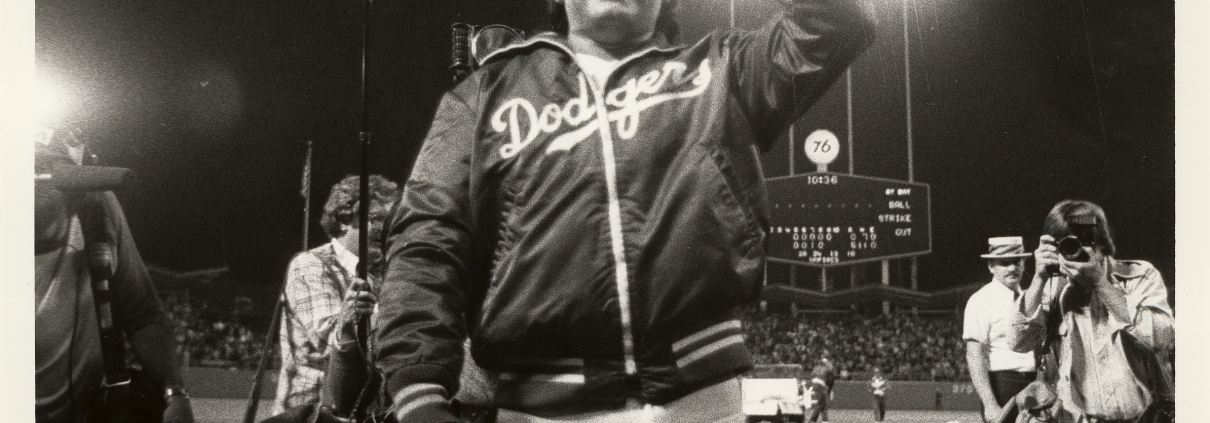

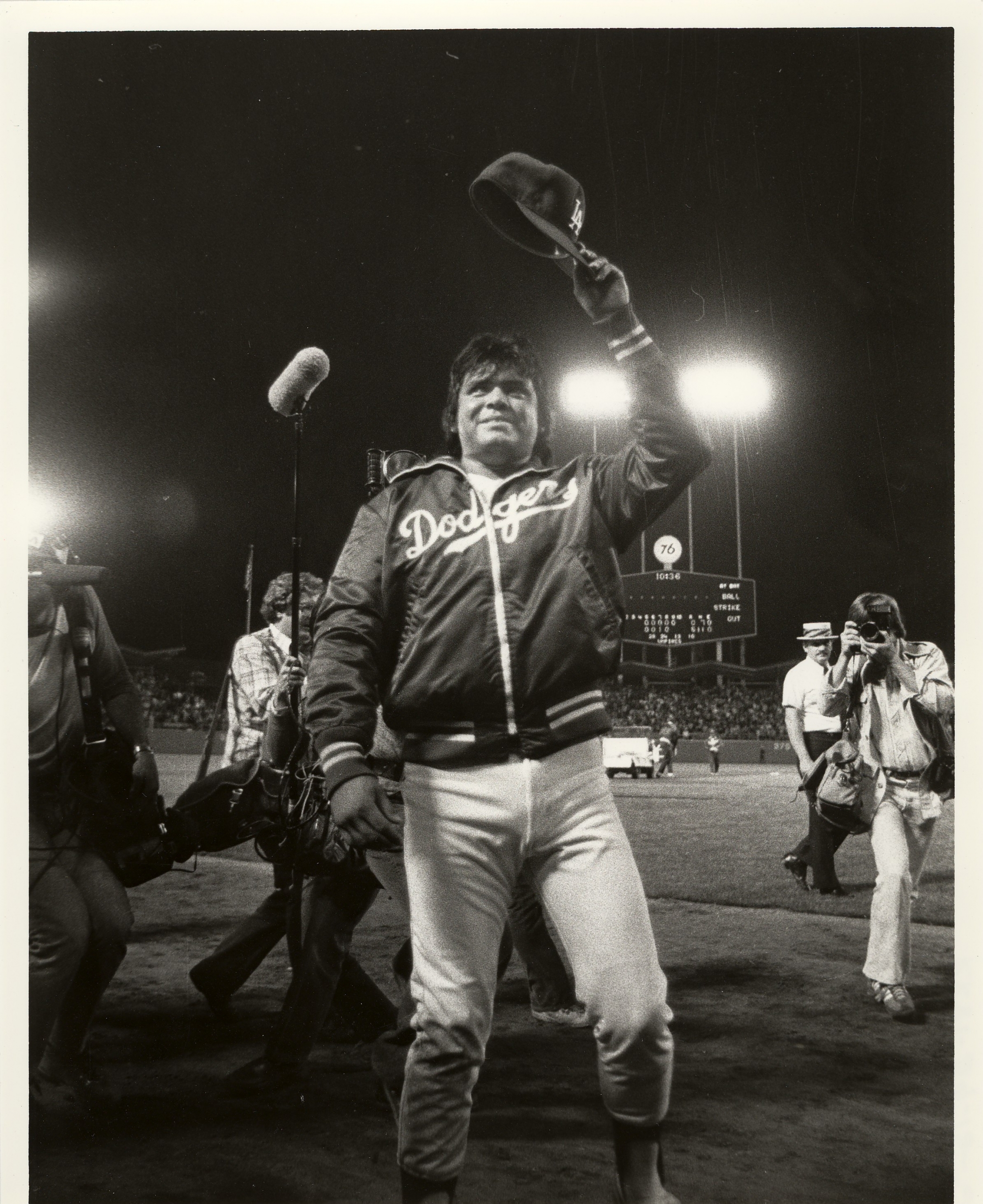

c) Bob and the Fat Man. On August 18, 1982, the Dodgers were in a marathon game at Wrigley Field; it had actually started the previous day, before being interrupted by darkness. In the 20th inning, disaster struck for the Dodgers when third baseman Ron Cey was ejected. With the team out of position players, right fielder Pedro Guerrero moved to third, while Fernando Valenzuela occupied right field. No one’s idea of a gazelle, Fernando then switched positions with left fielder Dusty Baker after two batters. In the 21st inning, someone (Tommy Lasorda had been ejected with Cey) decided that perhaps the pudgy Valenzuela was not the ideal outfielder, and more athletic pitcher replaced him: Bob Welch. Welch switched positions with Baker twice to minimize the risk of a ball being hit in his direction. Surprisingly, it would not be Valenzuela’s sole attempt at mastering another position. On June 3, 1989, a 22-inning marathon necessitated the Mexican’s presence, this time at first base, as infielder Jeff Hamilton gamely took the mound and first baseman Eddie Murray impersonated a third baseman. The Dodgers lost the game in the 22nd inning, when the Houston’s Rafael Ramirez hit a ball just past Fernando’s outstretched glove to drive in the game-winner.

d) The Pine Tar Game. The so-called “Pine Tar Game” between the New York Yankees and Kansas City Royals on July 24, 1983, is one of the most famous regular-season games in baseball history. When it resumed on August 18, with George Brett’s ninth-inning home run allowed to stand and four outs left to play, Yankees manager Billy Martin rolled out an unusual defensive line-up. It included lefty first baseman Don Mattingly playing second base, and pitcher Ron Guidry in center field. It was in part Billy’s way of protesting what he saw as an egregiously bad decision by American League president Lee MacPhail. When Guidry’s turn to bat came up in the bottom of the inning, Martin sent Oscar Gamble to pinch hit for him. Guidry has the unique distinction of having played two games in the outfield (he had previously been used there for an inning in a late-season game in 1979) but never coming to bat a single time in the regular season, as his entire career was spent in the DH-era American League before the beginning of interleague play. (He did bat a few times in the World Series, though.)

e) The Great Mets Pitcher Merry-Go-Round. On July 22, 1986, the New York Mets played a remarkable extra-inning game against the Cincinnati Reds. When Kevin Mitchell and Ray Knight were both ejected in the 10th inning, Mets manager Davey Johnson did not have enough position players left at his disposal to continue the game; he decided to send Jesse Orosco, who had been pitching, to left field and brought in Roger McDowell to relieve him. With two outs in the 11th inning, the two switched places, with McDowell going to the outfield and Orosco going back to the mound. In the 13th inning, they switched again, with McDowell finishing the game which ended in 14 innings.

f) How many pitchers can you use? On September 28, 1986, the San Francisco Giants and Los Angeles Dodgers were involved in an extra-inning contest. In the 13th inning, Giants manager Roger Craig sent pitcher Randy Bockus to pinch hit for an injured Robby Thompson. Bockus stayed in the game, playing the outfield, until the 14th inning when he was replaced by a pinch-hitter—pitcher Mike Krukow. As the game was not over, Craig then sent a third pitcher—Jeff Robinson—to play the outfield in the 15th. The game ended in 16 innings, before Craig had a chance to expend more of his moundsmen. It is not clear why Bockus was good enough to pinch hit in the 13th, but not to take his turn at bat in the 14th. Likely, Craig was playing things by ear by that point of the game.

g) Switch until you’re dizzy. Another interminable game caused the next situation. On May 14, 1988, with the game still tied in the 16th inning and no more pitchers available, Cardinals manager Whitey Herzog had to resort to desperate measures. Infielder Jose Oquendo, who had been playing first base, was sent to the mound while outfielder Duane Walker took over at first base, and the previous day’s starting pitcher, Jose DeLeon, neither nimble nor used to playing the outer depths, had to occupy an outfielder’s spot. It was a white flag move, but the makeshift line-up held on until the 19th inning against the Braves. During that time, DeLeon and fellow corner outfielder Tom Brunansky switched positions 11 times in an attempt to keep the ball away from the tall Dominican. In the bottom of the 19th, after the Braves had finally scored some runs against Oquendo, Herzog mercifully pinch hit for DeLeon—with another pitcher of course, John Tudor.

h) Will Somebody Give Me Some Hitters, Please. Billy Martin’s last stint as the New York Yankees’ manager ended on a strange note. On June 11, 1988, he wrote a line-up card that had Rick Rhoden as the designated hitter, batting seventh. Granted, Rhoden was an above-average hitter—for a pitcher—but, in what was the only instance in our study of a pitcher being the starting DH, Martin wanted to make a point: he did not have enough hitters on his roster. His starting line-up that day including such hitting weaklings as third baseman Wayne Tolleson, second baseman Bobby Meacham, catcher Joel Skinner, and shortstop Rafael Santana. Rhoden was not actually the worst hitter in the bunch. He did drive in a run with a sacrifice fly in the fourth inning that day; his point made, Martin replaced him in the fifth with pinch-hitter Jose Cruz, who was himself playing on fumes. Martin was fired less than two weeks after pulling this stunt.

THE BIG VOID, 2000-2006

By the end of the 1990s, the use of pitchers at positions other than the mound was down to a trickle, and from 2000 to 2006, not a single instance was recorded. The reason was simple. If pitchers were somewhat disposable in an earlier time, they had become more priceless than racehorses by the turn of the 21st century. With an average starting pitcher making somewhere between $5 and $10 million per season, only a foolhardy manager will risk using one in any situation that could cause injury, unless he is angling to be fired. This is not just some theoretical point. On August 30, 1981, with the Montreal Expos in a pennant race, manager Dick Williams decided to use ace pitcher Steve Rogers as a pinch-runner in an extra-inning game against the Atlanta Braves; Rogers succeeded in breaking up a double play, but he injured a rib in the process and was out two weeks while the Expos still lost the game. That was the final straw in getting Williams fired eight days later. Risking injury to one of your top starting pitchers is a steep price to pay for a move that is bound to attract a lot of criticism, no matter how well it may turn out.

But in baseball, circumstances do change. The 13-man pitching staffs alluded to earlier are a product of the recent decade. Even if Major League Baseball has made recourse to the disabled list much more flexible and allowed teams to bring up temporary replacements when players go on compassionate leave or paternity leave, there will again be situations when a team is simply out of players and needs to do something drastic to continue a game. After the seven-season hiatus, the recourse to using pitchers outside of their comfort zone on the mound is growing. We mentioned the Brooks Kieschnick experiment; both Cody McKay and Dave McCarty contemplated increasing their prospects for future major league employment by becoming two-way players. Each team now seems to have a utility player who can play four or five positions on its roster. Pitchers are being used regularly as pinch hitters because of a lack of other options—something that had not been seen since the 1930s and 1940s,[fn]Pinch-hitting pitchers never disappeared completely; Gary Peters in the 1960s, Ken Brett in the 1970s, and Dan Schatzeder and Don Robinson in the 1980s kept the species alive, but they were very much an exception during those decades.[/fn] and some like Carlos Zambrano and Micah Owings are asked to do so relatively frequently. There are bound to be more extra-inning marathons in the future and a demand to press pitchers into service elsewhere, if they are able to handle the duties. In 2007 and 2008, it happened once each year; in 2009, it happened twice, and twice again in 2010. We may be entering a time when there is a slight renewal of the practice.

But that said, one thing remains clear: Major League teams still treat their pitchers as being entirely different creatures from their position players, and a major revolution in thinking or playing style will be needed for that to change.

PHILIPPE COUSINEAU has been a member of SABR since 1998. A life-long fan of the Montreal Expos, he is a foreign service officer with Canada’s Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade and a member of the SABR Quebec chapter.

AUTHOR’S NOTE

The author would like to acknowledge the help provided by baseball-reference.com and retrosheet.org in writing this article. He would also like to thank members of the SABR Quebec Chapter for their feedback on this article, which originally took the form of an oral presentation on the first SABR Day, January 30, 2010.