Pitching Against Alzheimer’s: A Study of Baseball Reminiscence Programs

This article was written by Monte Cely - Barry Mednick - Lou Hernandez

This article was published in Fall 2022 Baseball Research Journal

There is not a person alive in the industrialized world who has not been touched directly or indirectly by the wonders of medical science. Death-sentence diseases of the past, like cancer, now carry longer and longer commutation periods, thanks to advanced early detection and modern surgical techniques. The twentieth century discovery of insulin has been a game-changer after generations of suffering from chronic high glucose blood levels. Vaccines to stop a once-in-a-hundred-year pandemic have been rolled out in record time, saving millions from death or disability.

However, there is no cutting-edge technology or panacea drug for most neurological disorders. The number of neurocognitive disorders is unfortunately many, including strokes, brain injury, Parkinson’s, and dementia. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention defines dementia as “not a specific disease but is rather a general term for the impaired ability to remember, think, or make decisions that interferes with doing everyday activities. Alzheimer’s disease is the most common type of dementia.”1 These disorders plague more members of our society every year, and place increasing degrees of physical and psychological burdens on their loved ones.

Alzheimer’s, as most people know, targets mostly seniors. “Alzheimer’s disease is a progressive neurological disease that causes the brain to shrink (atrophy) and brain cells to die,” explained a Mayo Clinic overview. “Approximately 5.8 million people in the United States 65 and older live with Alzheimer’s Disease. Of those, 80% are 75 years old and older. There is yet no treatment that cures Alzheimer’s or that alters the disease process in the brain.

Different programs and services can help support people with Alzheimer’s disease.”2 In other words, there is no medical cure for Alzheimer’s, and the focus for care-givers is on supporting the cognitive function and stimulation, emotional wellbeing, and overall quality of life.

A popular service program is reminiscence, recounting pleasant memories of the past. Reminiscence programs date back six decades. “Dr. Robert Butler, a psychiatrist with a specialty in geriatric medicine, first spoke of the idea of a ‘life review’ in the 1960s,” illuminated one health blog. “Butler … is credited with the idea that reminiscing could be therapeutic. At the time, psychiatrists did not think it was a good idea for people to always be ‘living in the past,’ but Butler disagreed and made it clear that reminiscence was a natural process of healthy aging.”3

Over the past few decades, reminiscence programs focused on music, singing, cinema, art and crafts have become popular offerings to people living with dementia. “Reminiscence therapy is a popular psychosocial intervention widely used in dementia care,” published the Dementia Services Development Centre Wales, Bangor University, Bangor, UK, in 2018. “It involves discussion of past events and experiences, using tangible prompts to evoke memories or stimulate conversation.”4

“For reasons not fully understood, nearly two-thirds of the people with memory loss are women,” cited the main webpage of Kensington Place Redwood City, one of California’s leading Assisted Living Facilities. “The most likely explanation is that women tend to live, on average, five years longer than men. This increases the likelihood of developing dementia.” That statistic notwithstanding, men are no less spared the feelings of loneliness and depression associated with these chronic disorders. “A new program primarily focused on men with Alzheimer’s Disease and other dementias was launched in Scotland in 2009 titled Football Memories,” informed the Kensington Place Redwood City ALF. “It focuses on getting groups of men together to reminisce about soccer, but it can easily be extended to include any popular sport.”5

More recently, baseball reminiscence programs have been viewed favorably as an effective means to enhance the well-being of those living with these debilitating diseases. Per an investigation by the Society for American Baseball Research (SABR): “The first baseball reminiscence program in the US was the Cardinals Reminiscence League (CRL), modeled on the Scottish programs. Begun in 2011, [CRL] was a joint effort by the Alzheimer’s Association, St. Louis University, the Veteran’s Administration, and the St. Louis Cardinals Hall of Fame and Museum.”6

Beginning in 2015, SABR volunteers in Austin, Texas—led by Jim Kenton and working with Alzheimer’s Texas—began offering a program based on the Cardinals Reminiscence League model. For Jim, the volunteer work struck a personal chord. “My father had dementia in his later years,” he recounted. “He served in the Navy, and there were times he didn’t know who I was, but he had a book with pictures of the ships he served on, and I could always count on that book to get the conversation going [between us]. When I read about the CRL program, it combined two different loves. I’ve been a baseball geek all my life, and since I retired the opportunity to serve others in memory of my dad, and what he went through, led us to start the program here.”7

To help more broadly characterize the initiative in Austin, “Talking Baseball” was adopted as its program name (still in use today). The work of Jim and his associates has been enthusiastically received, based on comments like this from an enthusiastic Austin care partner: “You are really on to something. My husband has had Alzheimer’s for 11 years that we know of; he and I have been part of a variety of programs to respond to the challenges of dementia. The Baseball Memories group that you have created is at the top of that list. You have a real gift for bridging the divide that can result from this disease.”8

The baseball-themed gatherings have also become popular with organizations that serve people with other long-term health issues, up to and including long-term institutionalization. “It is amazing to see some of our closed-off veterans initiate conversations and even socialize in group settings who normally do not,” said a staff member from the Kerrville, Texas, Veterans Administration Hospital. “It gives our residents a comfortable way to ease into conversation allowing opportunities to share experiences and even have an occasional laugh.”9 The partners and participants at Kerrville refer to their program as “The Baseball Guys.”

Similar SABR-led programs not only expanded to multiple sites in Texas, but to Westchester County, New York, and Cos Cob, Connecticut, over the next few years. In 2018, SABR’s Los Angeles chapter reached out to Alzheimer’s Los Angeles, a local non-profit services organization. That contact evolved into a full-fledged sponsorship for their program, called “BasebALZ.”

“SABR has worked closely with Alzheimer’s LA to deliver the BasebALZ program, a reminiscence program that uses baseball as a topic to invoke and discuss memories of participants with Alzheimer’s disease or other types of dementia,”10 stated Anne Oh, Manager, Support Groups & Activity Programs for Alzheimer’s Los Angeles. “BasebALZ is one of our most popular and effective programs at Alzheimer’s LA. The program encourages participants to tap into their own memories, specifically around the topic of baseball. You can see how just talking about baseball lights our participants up. They have so much to share, whether childhood memories of playing, meeting a past baseball player, or simply about being at a game. Simple triggers like holding a baseball or singing, ‘Take Me Out to the Ballgame,’ which Jon [Leonoudakis] has them do every session, brings back those enjoyable memories.”11

“I love the program,” expressed one participant in the Los Angeles program to co-host Jeff Hubbard. “It is marvelous.”12

“I’m 91 years old and love the quizzes,”13 chimed a nonagenarian partaker from the same group.

Another happy partnership involved the West Los Angeles VA Home for Heroes. “The program stimulates their [participants’] long-term memory, improves self-esteem, and self-efficacy,” shared the partner liaison at the Home for Heroes. “It’s top-notch with so many benefits, and attendance has grown steadily in 2021. The last session had 13 attendees; nearly all are in wheel-chairs and walkers with seats.”14 When asked about additional benefits, the liaison mentioned, “Socialization. Baseball Memories attracts people who don’t typically engage in most of our programs, as they are very independent individuals. There’s a good amount of buzz about the program among our group here.”15

Baseball Memories programs are customized by the local volunteers to appeal to their particular audiences of participants and attending care partners. The program “branding” is intended to have both meaning and local appeal, and is used by local partners to market the program. Examples (some mentioned above) are “BasebALZ,” “Talking Baseball,” “The Baseball Guys,” “The Baseball Hour” (in New York), “The Cardinals Reminiscence League,” and currently “Baseball Memories.” While agendas and content vary, baseball reminiscence programs generally share these characteristics:

- They are offered bi-weekly or monthly; either in-person or online.

- Length is from one to two hours.

- Singing is popular—usually “Take Me Out to the Ballgame,” the National Anthem, and any other songs that may invoke pleasant memories of the past.

- One or two baseball topics are presented for discussion.

- Other reminiscence topics are woven in (e.g. TV and radio shows, cinema, history).

- Additional indoor or outdoor activities (e.g. a Twist contest, Wiffle ball soft toss or batting practice).

While the programs were initially targeting those living with Alzheimer’s, it quickly became apparent to program volunteers that the care partners were equally important customers of these programs. “One in five full-time workers in the United States is a caregiver,” according to a Rosalynn Carter Institute for Caregivers survey released in September 2021. “About 45% of family caregivers who are employed full time said they had to go part time at some point and roughly two in ten said they had to quit their jobs altogether.”16 Care-givers are highly involved, and baseball reminiscence program content and activities have evolved to be inclusive of the caregiver as well as their partner.

REASONS FOR THE STUDY

In 2020, the SABR Board of Directors embraced baseball reminiscence by formalizing a Baseball Memories Chartered Community. This group now acts as an enabling force to promote the widespread adoption of baseball reminiscence programs. Since this broader effort was initiated in the summer of 2020, new programs were implemented in Cleveland, San Diego, and Las Vegas. SABR members are currently exploring program possibilities in many more locations.

Under the umbrella of SABR’s Baseball Memories Chartered Community, a Baseball Memories Research Study was launched to explore the effects of baseball reminiscence programs in an organized, consistent, and professional manner. Key goals and objectives were to “gather both quantitative and qualitative data, producing reports that will aid our outreach and help further promote awareness.” Likewise, fundamentally to “get more people involved, through members and volunteers…including family and friends. We wish to reach more potential partner organizations, in order to reach still more participants and their care partners.”17

As outreach continues, prospective partner organizations may ask for evidence concerning the effectiveness of these programs. This study was intended to gather both quantitative and qualitative data to address that question.

METHODOLOGY

Overview

A “pilot” study of the effectiveness of the various baseball reminiscence programs was established relevant to the number of current participants and care partners. It accumulated quantitative data on respondents’ quality of life, as well as both quantitative and qualitative data on their views of the programs, using measurement tools that are minimally intrusive. Introduction letters to its partner organizations (Alzheimer’s Associations, VA groups, all others) and potential participants and care partners were standardized. Targeting both Alzheimer’s and other dementia sufferers, as well as other participants (those isolated, with long-term disabilities, institutionalized), consent forms and confidentiality agreements were written to adhere to ethical standards. Survey questionnaires and an interviewer’s guide were developed to serve as tools to promote consistency and avoid bias in the execution of the Baseball Memories Research Study. The supporting literature review and details about the study design follow.

Literature Review

Two research reports were issued on the original Cardinals Reminiscence League baseball program.18 Both studies reported positive results in terms of the feasibility of baseball reminiscence offerings, of improvement in participants’ engagement and enjoyment, plus willingness of all parties to continue the programs. They also stressed the need for a more controlled study with more participants over a longer time frame.

Researchers at Clemson University planned and executed a quasi-experimental study using Clemson collegiate football as the reminiscence topic.19 In addition to affirming the findings from the CRL studies, the Clemson study was able to report quantitative data on improvement in quality-of-life measurements (an overall improvement of 14–18% that was statistically significant). A small improvement in cognition measurements was also reported, although the authors cautioned as to the significance of this finding due to the small sample size and inability to control outside influences. The authors stressed the need for more research, and also the extension of the research beyond Alzheimer’s/dementia subjects to include older adults experiencing loneliness or social isolation.

Study Design

Baseball Memories and participating partners can provide the number of programs and participants, plus the longevity, to conduct an assessment of the effectiveness of baseball reminiscence programming. Over time, this will provide a significant base of programs, participants, care partners, and volunteers for study.

Baseball Memories envisioned focal points for a study of baseball reminiscence to be:

- Gather quality-of-life data from participants and care partners, with an interest in how reminiscence programs affect human perceptions of well-being.

- Gather both quantitative data for measurement of program effectiveness and qualitative data for evaluation and program improvements.

- Gather supporting data from volunteers.

- Use existing, widely-used measurement tools if possible.

- Include participants with varying lengths of exposure to our programs (with expectations to have participants that are brand new to the program, as well as those with longer involvement).

- Include both Alzheimer’s and other dementia participants as well as other adult participants (those isolated, with long-term health issues, or institutionalized).

- Be easy to administer and minimally intrusive.

- Be able to re-sample periodically so as to support longitudinal evaluation.

Considering the current number of baseball reminiscence programs in operation, and the fact that some have been suspended or otherwise negatively impacted due to the COVID-19 pandemic, Baseball Memories evaluated how much participation it could reasonably expect near-term. Taking into account the statistical significance of the number of respondents that the investigative group could realistically expect to participate, and its desire to measure both program effectiveness as well as quality-of-life impacts, Baseball Memories chose to break its research effort into two phases:

Phase 1 (also referred to as the “Pilot” study) was an evaluation of the effectiveness of existing baseball reminiscence programs. It gathered both quantitative and qualitative data from current participants, care partners, and volunteers, with a set goal of at least thirty interviews with participants and care partners, as well as a self-administered survey to be completed by volunteers. A one-year time schedule was developed to achieve this, with the “clock” starting April 1, 2020.

Phase 2 (Informed by the results of Phase 1) Baseball Memories envisions a follow-on study(s) with a larger sample size enabled by continued adoption of baseball reminiscence programs. This will provide for further evaluation of the impact on respondents’ quality of life over time, and with stronger statistical significance.

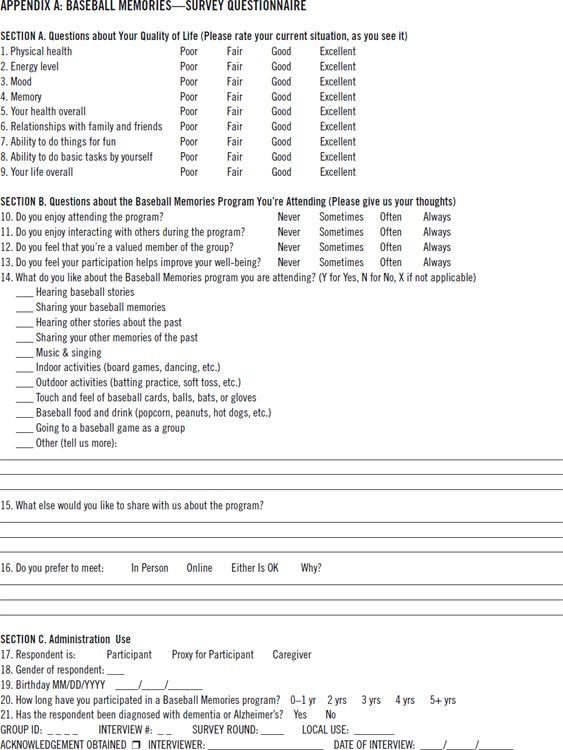

To meet its goals, Baseball Memories constructed a survey questionnaire with three sections:

A. Quantitative quality-of-life questions

B. Quantitative and Qualitative questions about respondents’ evaluation of our programs

C. Demographic questions

In addition to the research previously cited, also conducted was a literature review of Quality-of-Life (QOL) measurement tools. The summary paper by Bowling, et.al. was particularly useful in comparing strengths of various quality-of-life measurement instruments.20 While several of these instruments were shown to be highly effective, it was determined that they were too time intensive and too intrusive for the baseball reminiscence audience. Consequently, Baseball Memories developed a set of nine quantitative QOL questions that were deemed more appropriate, less intrusive, and could be easily answered.

For the questions relating to program evaluation, Baseball Memories sought respondents’ feedback about their experiences attending the baseball reminiscence offerings. In particular, was the experience enjoyable? Did the program promote a sense of community among the attendees and volunteers? Did the program add to their self-esteem and overall sense of wellbeing? What program components did they like; not like? A set of four quantitative and three qualitative questions was developed to gather this feedback.

Baseball Memories also wanted to gather demographic data and therefore included questions about the respondents’ age, sex, length of time attending a baseball reminiscence program, and whether or not they had been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s/dementia. The resultant questionnaire used with participants and care partners is included as Appendix A.

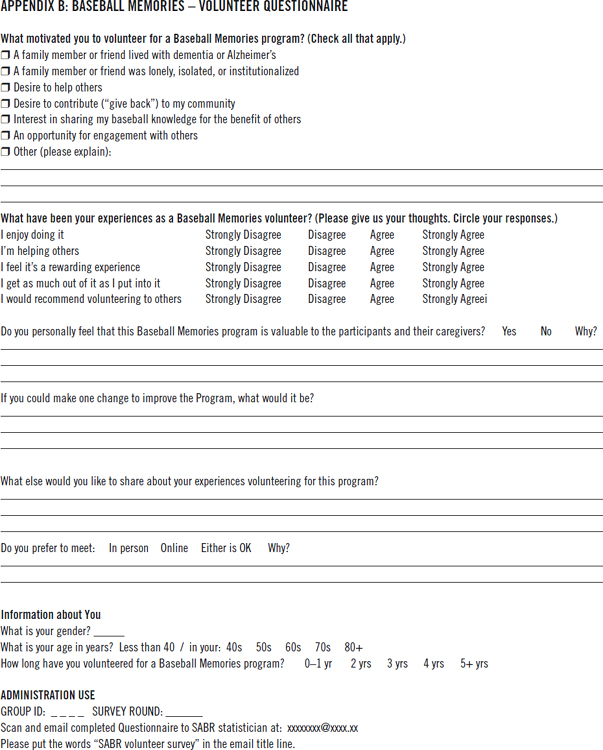

Finally, a separate volunteer questionnaire that could be self-administered by our program volunteers became of standard use. This questionnaire asked volunteers about their motivation(s) to participate, their experiences as volunteers, and their feedback and suggestions about program content and delivery. The Volunteer Questionnaire is included as Appendix B.

RESULTS

Survey data were collected throughout the summer and fall of 2021. SABR program volunteers interviewed participants and their care partners, using the Baseball Memories Survey Questionnaire (Appendix A). Program volunteers self-administered the Baseball Memories Volunteer Questionnaire (Appendix B). All results were submitted to the project statistician for compilation and analyses.

Demographics

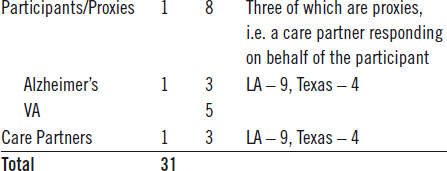

A total of 31 participant and care partner responses were received. These responses came exclusively from SABR’s well-established programs in Los Angeles (at Alzheimer’s LA and the Veteran’s Administration Home for Heroes) and Texas (at the Alzheimer’s Texas offerings in Austin and Georgetown). The 31 responses consisted of:

Twenty-five (25) volunteers submitted responses. These responses represented active volunteers based broadly across established and newer programs:

- Las Vegas: 1

- Los Angeles: 3

- Texas: 14

- St. Louis: 2

- Cleveland: 3

- New York: 1

- Not identified: 1

- Total: 25

Participants and their care partners were mostly born in the 1940s and 1950s and reflected partner couples. A few of the care partners were younger, generally representing adult children of the participants. Participants and care partners reported, on average, having attended a baseball reminiscence program for 2+ years. A handful of Texas respondents have been involved for five or more years. Responding participants were all men, while the care partners were almost all women (only one responding care partner was male).

Likewise, volunteers were mostly aged in their sixties or seventies. Volunteers’ involvement averaged 3+ years overall, with over one-third of the volunteers reporting having been active for five or more years. Volunteers were mostly men, with only two of the twenty-five volunteer respondents being women.

Quality of Life

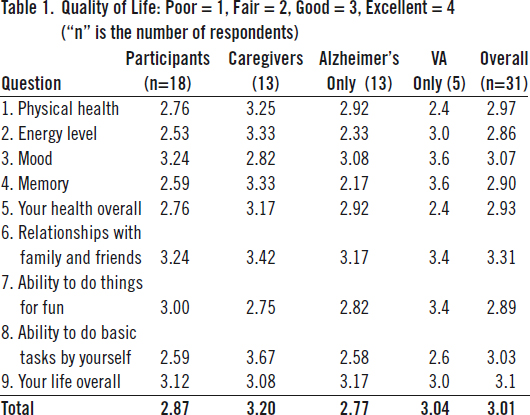

The survey questionnaire contained nine “Quality-of-Life” questions. Respondents were asked to gauge their current situation using a four-point scale. Mean scores for the participants and care partners can be seen in Table 1 below.

Very few respondents (3) answered with the same score for all nine questions. Likewise, individual answers varied. The difference between caregivers’ and participants’ responses was statistically significant. All of these factors indicate that the respondents gave due consideration to answering the questionnaire. Feedback from the interviewers reinforces this: The respondents took the survey seriously and answered honestly.

The care partners’ composite assessment of their quality of life (3.20) was higher than the participants living with dementia (2.77). Participants at the VA, who generally were dealing with chronic health issues other than dementia, rated in between (3.04). Overall, the total composite score of 3.01 indicates the respondents as a whole rated their quality of life as “Good.”

Program Evaluation

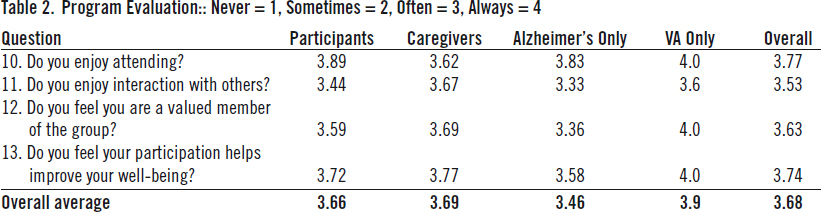

The survey questionnaire contained both quantitative and qualitative questions about respondents’ assessment of the Baseball Memories program they were attending. The four quantitative questions asked respondents to rate the value they received from the program, in terms of the frequency they felt they received that value. Respondents were asked to express their true feelings, and not necessarily what they thought the interviewer might want to hear. They were asked to respond using a four-point scale. Mean scores on the quantitative questions are in Table 2 below):

Feedback as to respondents’ evaluation of the programs was highly positive among all subgroups of attendees. Respondents enjoy the programs and feel strongly that their participation is a plus for their wellbeing.

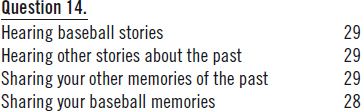

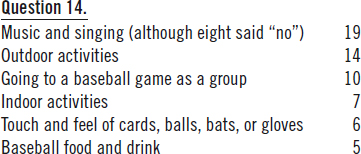

When asked about specific aspects of the Baseball Memories programs they were attending, respondents said almost unanimously that they liked:

Hearing and sharing baseball stories and memories, and generally memories of the past, are key elements of all baseball reminiscence programs.

Other aspects of program content tend to be location-specific or have been impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic that has forced most programs to switch from in-person to online sessions over the last two years. Yet, these approaches can be valuable and should be considered when programs return to in-person sessions:

An example of a pandemic effect is the feedback on singing. This is popular in-person but more difficult to do online, thus generating the most negative responses.

Respondents were asked to further comment on program components (Q14) and to share anything else that they felt was noteworthy (Q15). These open-ended questions generated over ninety comments and suggestions. Some key, often-mentioned topics were:

- The facilitators, volunteers, and guest speakers do a great job.

- High level of satisfaction with the program. It’s valuable for both participants and caregivers. Likewise, the program is valuable for both men and women.

- The frequency and length of the programs are about right. If anything, respondents would like to attend even more often.

Some representative quotations are:

- “The best part of the program is how you make sure everyone is involved.”

- “I love the program. It is marvelous. It is perfect just as it is.”

- “It’s healthy for us to have some way to socialize. The program provides that.”

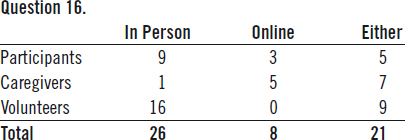

The final program evaluation question asked for respondents’ preferences for meeting online or in person. The same question was also posed to volunteers:

There was a distinct preference for meeting in person. Participants and volunteers felt there are multiple benefits to interacting “live,” such as more personal contact, ability to activate other senses such as handling baseball equipment and memorabilia, the smell of “ballpark food,” and doing outside activities.

Care partners did have some preference to meet online. They cited inconvenience in preparation and avoiding longer drives in traffic. Volunteers in Los Angeles stated that their program participation actually increased when their program went online due to pandemic concerns. Some specific feedback was:

- “In person is easier to interact with others.” “ I like sharing in person.”

- “In person is better. Socialization is important. I like the hybrid idea of doing both in person and online.”

- “Online is easier”

- “Fridays in L.A. just don’t work. Please keep the meetings online.”

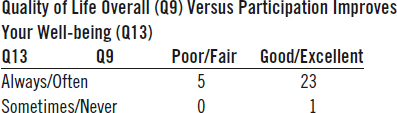

Impact of Programs on Quality of Life

Both quantitative and qualitative data strongly suggest that attending a Baseball Memories program has a positive impact on the quality of life of participants and their care partners. When asked if their participation helps improve their well-being (Q13), 97% of respondents answered either “always” or “often.” By comparison, when asked to rate the quality of their life overall (Q9), 83% said it was “good” or “excellent.”

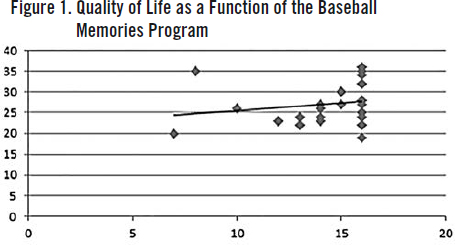

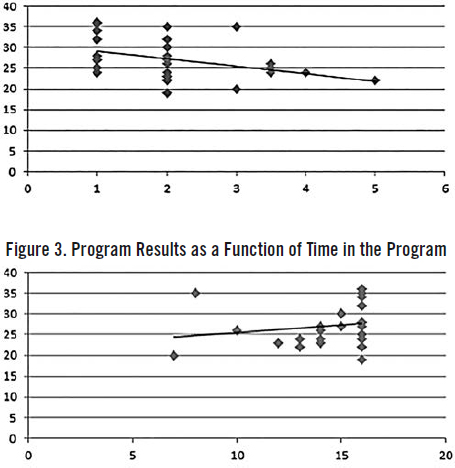

When comparing the sum of respondents’ QOL scores (y axis, Q1-Q9 – max score 36) as a function of the sum of their Baseball Memories Program Evaluation scores (x axis, Q10-Q13 – max score 16), we see the following relationship:

This reflects a weak positive correlation, due to the strong overall scores given to the program itself (x axis) and the many impacts on their QOL that are outside the scope of this study. It appears that, regardless of the respondents’ self-evaluation of their QOL (y axis), they feel strongly that the Baseball Memories program is a positive experience for them.

Qualitative comments related to the impact of the programs on respondents’ Quality of Life reinforce this positive relationship:

- “I strongly believe this program makes a difference in the lives of everyone involved. Life is very hard for everyone now and this program helps.”

- “My husband has great baseball memories, and it means the world that he gets to share them.”

- “The program has changed our lives.”

The following two charts reflect Quality of Life (sum of responses to the nine QOL questions) and Program Results (sum of responses to the four Program Evaluation questions) plotted against respondents’ time attending a Baseball Memories program (in years):

Figure 2. Quality of Life as a Function of Time in the Program

Respondents’ assessment of their Quality of Life declines over time due to advancing age and increasing effects of Alzheimer’s or other chronic health issues, whereas their views as to the value they get from attending a Baseball Memories program holds steady.

Volunteer Results

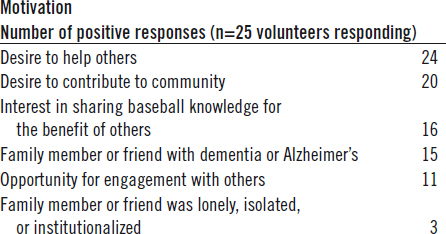

The self-administered questionnaire (Appendix B) asked volunteers to provide feedback on their motivation to participate in a baseball reminiscence program and their experiences doing so. A desire to help others and give back to the community were strong factors, especially when combined with a family member or friend having dealt with dementia or other chronic health issues:

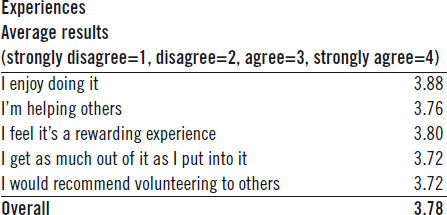

Volunteers’ experiences with the program were consistent with their motivation for getting involved. There was strong agreement among volunteers that they were, indeed, helping others. In a related question, 96% of volunteers (23 of 24 responses) stated they felt the program was valuable to the participants and care partners. In addition to being valuable to that audience, volunteers felt their own experiences were both enjoyable and rewarding. Volunteers strongly felt their efforts were worthwhile, and they would highly recommend volunteering to others.

In addition to the quantitative results above, volunteers provided over seventy qualitative responses about the program. Some of the often-mentioned statements are:

- Strong sentiments expressed as to the positive value of the program for all involved.

- Would like to get back to in-person sessions.

- Need to continually focus on content that’s of interest to the participants and their care partners; and will get the participants talking.

- Need more women volunteers.

A few verbatim comments from volunteers are:

- “I see the energy that participants exhibit during the sessions. I’ve had both participants and caregivers tell me directly of its value.”

- “Not a medical program. A time to forget about their problems. People with like issues to talk to.”

- “It is an incredibly rewarding experience.” “So glad I did it.”

- “To be able to meet in person.” “… get the on-site meetings going again instead of online”

- “More women volunteers. The women caretakers are more likely to open up to other women about sensitive problems.”

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

This study was able to gather both quantitative and qualitative data that demonstrate the value of baseball reminiscence programs. Participants, their care partners, and program volunteers all strongly expressed that the programs were very worthwhile and had a positive impact on all involved. Furthermore, this study was able to quantify these results, reinforcing the qualitative and anecdotal feedback that volunteers have often received.

The study results also demonstrate that baseball is a strong topic for reminiscence that is especially meaningful for the current generation of participants and their care partners. Born mostly in the 1940s and 1950s, they have deep and varied memories of playing, watching, listening to, and reading about baseball during the sport’s peak as the national pastime.

The study results identified issues for further consideration by program leaders. Most frequently mentioned were:

- Resuming in-person vs. continuing online programs post-pandemic. Most respondents indicate a desire to return to in-person meetings due to added benefits of being able to interact in person. However, there are some distinct advantages for care partners and program accessibility to meeting online.

- Frequency of program offerings. Qualitative feedback suggests that participants and care partners would like more frequent programs. There was no sentiment expressed for less-frequent scheduling.

- Need for more female volunteers. Due to the large percentage of female care partners, more female volunteers would help further improve program quality and inclusiveness.

- Value of singing within online programs. Music and singing are valuable components for reminiscence programs. However, the latency inherent with Zoom sessions makes this problematic for online offerings. A solution is needed.

- Set expectations for the proper level of participation for care partners. Some care partners are concerned about participating too much and taking away sharing opportunities from participants.

The data analyses suggest several topics for future study:

- Conduct a controlled, longitudinal study of a new group of participants/care partners. Such a “before and after” study would provide more data as to the correlation of respondents’ quality of life with their assessment of the value of baseball reminiscence. Due to the pandemic and staffing turnover at partner organizations, we were not able to do this during the Phase 1 effort.

- Seek a larger sample size from more programs nationwide. This would provide a broader look at more respondents in more varied program offerings, resulting in even more meaningful results. This should be able to be accomplished in a post-pandemic setting as baseball reminiscence programs continue to proliferate.

- Assess the value of more frequent program offerings. Explore if more-frequent attendance results in higher satisfaction and improved quality of life.

As discussed earlier, a future Phase 2 study is contemplated that can address these additional topics and more. A potential sample size of one hundred or more respondents, spread across five-to-ten programs nationwide, should be attainable goals—over the next several years—to trigger consideration for a follow-on study.

In closing, the quantitative and qualitative data from this study have clearly shown that baseball reminiscence programs positively impact the well-being of not only persons with Alzheimer’s and their care partners, but also those dealing with chronic health issues, isolation and loneliness. Baseball with its heritage as our national pastime is an excellent broad, diverse topical area that can be used to generate group sharing sessions that impact participants and their care partners in a most positive way. The study results have also highlighted important questions that could be the subject of future studies. Answers to the questions could play an important role in helping shape the future direction of the program as an expansion to a national level of involvement and impact is planned and implemented.

Finally, the data gathered and presented in this report demonstrate that these programs are worthwhile and rewarding experiences for volunteers. Coupled with the positive results for participants and care partners, a continued increase in the number and availability of baseball reminiscence offerings would be a most beneficial way for baseball fans to serve their communities.

LOU HERNÁNDEZ is the author of multiple baseball histories and biographies, and two young adult fantasy novels. He resides in South Florida and follows the Miami Marlins.

MONTE CELY has authored two previous BRJ articles on the Cy Young Award and has researched early twentieth century spring training in Marlin, Texas. Monte and his wife Linda, a retired registered nurse, reside in Round Rock, Texas, an Austin suburb.

BARRY MEDNICK is president of the Los Angeles SABR chapter. A SABR member for 40 years, he has written several baseball related articles. In real life, he works in high-tech and lives in Yorba Linda with his wife Leslee Newman, a family law attorney.

Appendix A

Appendix B

Authors’ Note

This report is the result of the work of a project team of Society for American Baseball Research (SABR) volunteers. The study was conceived, approved, planned and executed from April 2021 to January 2022. In addition to the authors, significant contributions were made in project planning and analysis by Joe Shaw, Jeff Hubbard, Linda Cely, Jerald Thomas, Rob Sheinkopf, and Tad Myre. Furthermore, Jeff Hubbard, Jim Kenton, and Jon Leonoudakis all played key roles in coordinating with local partner organizations, participants, and care partners to conduct interviews and gather volunteer data. The authors sincerely thank all of these dedicated individuals for their efforts.

Sources

“What is Diabetes?” Accessed October 25, 2021: https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes.html.

“Neurological Disorders.” Accessed October 25, 2021: https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/neurological-disorders.

Monte and Linda Cely. Baseball Memories Study Report, November 11, 2021.

Notes

1. “What is Dementia?” Accessed October 25, 2021: https://www.cdc.gov/aging/dementia/index.html. Also, per the CDC, besides age—family history, race/ethnicity, poor heart health and traumatic brain injury are factors that increase the risk for dementia. Older African Americans are twice more likely to have dementia than whites. Hispanics 1.5 times more likely to have dementia than whites.

2. “Alzheimer’ disease.” Accessed November 17, 2021: https://ww.may-oclinic.org/diseases-conditions/alzheimers-disease/symptoms-causes/syc-20350447. “Alzheimer’s disease is named for a German psychiatrist and neuropathologist named Alois Alzheimer. While conducting a postmortem in 1906, the doctor noticed abnormalities in the brain of a woman with a mysterious illness that caused memory loss, language problems, unpredictable behavior, and ultimately death. Alzheimer’s disease causes nerve cells (neurons) to stop functioning, lose their connections with other neurons, and die.” Pamela Kauffman. “What is Alzheimer’s Disease? Symptoms, Cures, Diagnosis, Treatment and Prevention.” Medically Reviewed by Sanjai Sinha, MD., February 27, 2020. Accessed November 18, 2021: https://www.everydayhealth.com/alzheimers-disease/guide.

3. Dr. Robert Butler. “Reminiscence Therapy.” Accessed November 18, 2021: https://lifebio.blogspot.com/2010/10/reminiscence-therapy-dr-robert-butler.html.

4. Laura O’Philbin, Bob Woods, Emma M. Farrell, Aimee E. Spector, Martin Orrell (2018): “Reminiscence therapy for dementia: an abridged Cochrane systematic review of the evidence from randomized controlled trials.” Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. Accessed October 26 and November 18, 2021: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/14737175.2018.1509709.

5. “Sports Reminiscence Therapy is on the Horizon.” Accessed October 26, 2021: https://kensingtonplaceredwoodcity.com/sports-reminiscence-therapy. Currently, Scotland has over 300 reminiscence programs nationally, covering multiple popular sports such as soccer, golf, rugby and shinty, including popular culture topics such as music and cinema memories.

6. Jeff Hubbard, Ed.D., Linda Cely, R.N., Monte Cely, M.Sc. “Proposal: Baseball Reminiscence Research Study. Version 1, January 7, 2021, Version 2, January 21, 2021.”

7. BasebALZ—A Baseball Reminiscence Program; YouTube Accessed December 10, 2021: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-l6YDWsbcyc.

8. About BasebALZ —Society for American Baseball Research, Rogers Hornsby Chapter (sabrhornsby.org). Accessed December 10, 2021: www.sabrhornsby.org/about-basebalz.

9. About BasebALZ—Society for American Baseball Research, Rogers Hornsby Chapter (sabrhornsby.org). Accessed December 10, 2021.

10. Anne Oh. Alzheimer’s Los Angeles. Letter of Recommendation. December 14, 2020.

11. Anne Oh BasebALZ testimonial. Accessed December 10, 2021: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WlpmzkzWuPA.

12. Jeff Hubbard. Baseball Memories Interviews, number 9, Alzheimer’s Los Angeles, July 20–21, 2021.

13. Jeff Hubbard. Baseball Memories Interviews, number 16, Alzheimer’s Los Angeles, July 20–21, 2021.

14. Jon Leonoudakis. Baseball Memories Interview. West Los Angeles Veteran’s Administration Home for the Heroes, October 12, 2021.

15. Jon Leonoudakis. Baseball Memories Interview, October 12, 2021.

16. Leah Willingham. Associated Press. “For 112-year-old veteran’s daughter, care is a labor of love.” Miami Herald, October 31, 2021, Extra, Nation, 11. Caregivers are described as a family member or compensated helper that regularly looks after an infirmed, elderly or disabled person. In states like New York, residents can be compensated as family caregivers, if they meet the necessary requirements.

17. Monte Cely and Joe Shaw. Baseball Reminiscence Chartered Community, May 27, 2021.

18. Cheryl Wingbermuehle, et.al. “Baseball reminiscence league: a model for supporting persons with dementia,” Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 2014. Nina Tumosa. “Baseball Reminiscence Therapy of Cognitively Impaired Veterans,” Federal Practitioner, 2015.

19. Brent Hawkins, et.al. “Creating Football Memories Teams: Development and Evaluation of a Football-Themed Reminiscence Therapy Program,” Therapeutic Recreation Journal, Vol. LIV, No.1, 32–47, 2020.

20. Bowling, Ann, et.al. “Quality of life in dementia: a systematically conducted narrative review of dementia-specific measurement scales,” Aging and Mental Health, 2014.