Player Movement Throughout Baseball History: How Has It Changed?

This article was written by Brian Flaspohler

This article was published in 2000 Baseball Research Journal

I’ve often heard baseball announcers, former players and coaches, and knowledgeable fans complain that players don’t stay with the same team the way they did in the old days. My feeling is that players have always switched teams a lot. This paper is an analytical look at player movement among teams from the beginning of the National Association in 1871 through 1999.

I defined a team switch as any time a player plays for two different major league teams (obviously!) I used the team history section in the fifth edition of Total Baseball to determine exactly what a team switch was. Any team that switched a city or a league, but was the same franchise (such as the Brooklyn Dodgers moving to Los Angeles or the Milwaukee Braves moving to Atlanta) is not considered a switch. In a well-known twentieth century instance, the city and league remain the same but the franchise is different (Washington Senators, 1960 and 1961—three players played for both teams, and each was credited with a team switch.) A midseason switch is counted when a player accumulated statistics for different major league teams during the same year.

For every player who has ever appeared in what I consider a major league game (National and American Leagues, National Association, American Association, Players’ League, Union Association, and Federal League), I compiled the player’s debut year, the total number of seasons played, the number of times the player switched teams, the number of times the player switched teams in midseason, and the final year the player appeared in a major league game. For example, a player’s “switch history” would look like this: Jim Kaat, 1959, 25, 4, 3, 1983. Translated, this means that Jim Kaat debuted in 1959, appeared in twenty-five major league seasons, switched teams four times (Washington, 1960 to Minnesota, 1961 is not counted as a switch), three times during a season, and played his final game in 1983.

Categorization

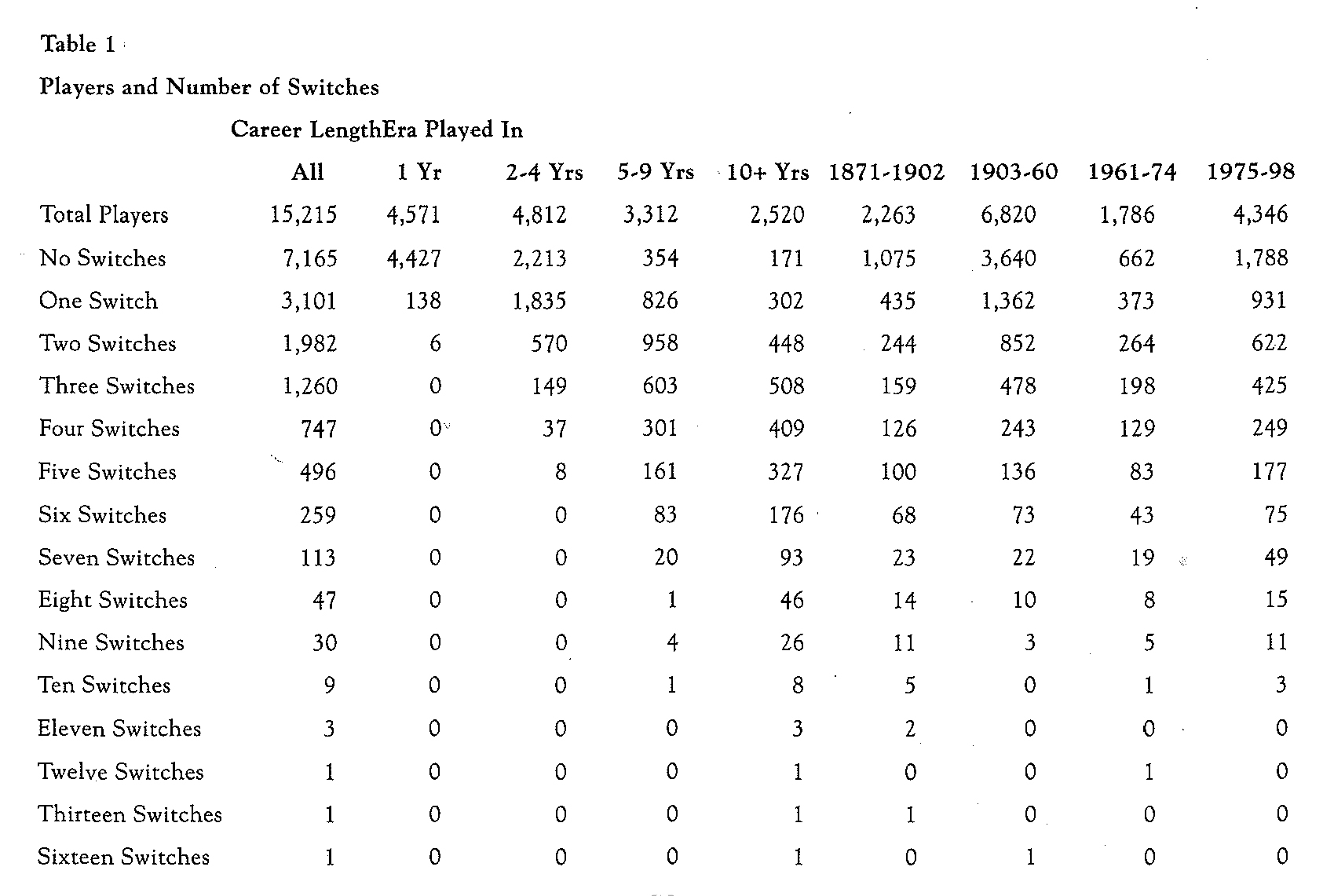

I divided the 15,215 players who played major league baseball during the span I studied into four eras of baseball history: Nineteenth Century (1871-1902, 2,263 players), Golden Age (1903-1960, 6,820 players), Expansion (1961-1974, 1,786 players), and Free Agency (1975-1999, 4,346 players). I put players whose careers crossed eras into the era in which they played most. If they played the same number of years in each era, I put them in the more recent era.

I also categorized players by career length. The divisions: One Shots (one-year career, 4,571 players); Short Timers (two- to four-year careers, 4,812 players); Journeymen (five-to nine-year careers, 3,312 players); and Stars (ten-year careers or longer, 2,520 players). I also developed a subset of Stars, Superstars (fifteen-year careers or longer, 747 players). Obviously not every ten-year player is a true star, but career length correlates reasonably well with ability.

Table 1 is the summary of the compiled data. It shows the number of players by era and by career length sorted by the number of team switches during the players’ careers. As you can see, one player switched teams sixteen times during his major league career. No one else is close to this guy’s record. Keep reading to discover the name of this guy who perpetually had his bags packed.

Team switches through history

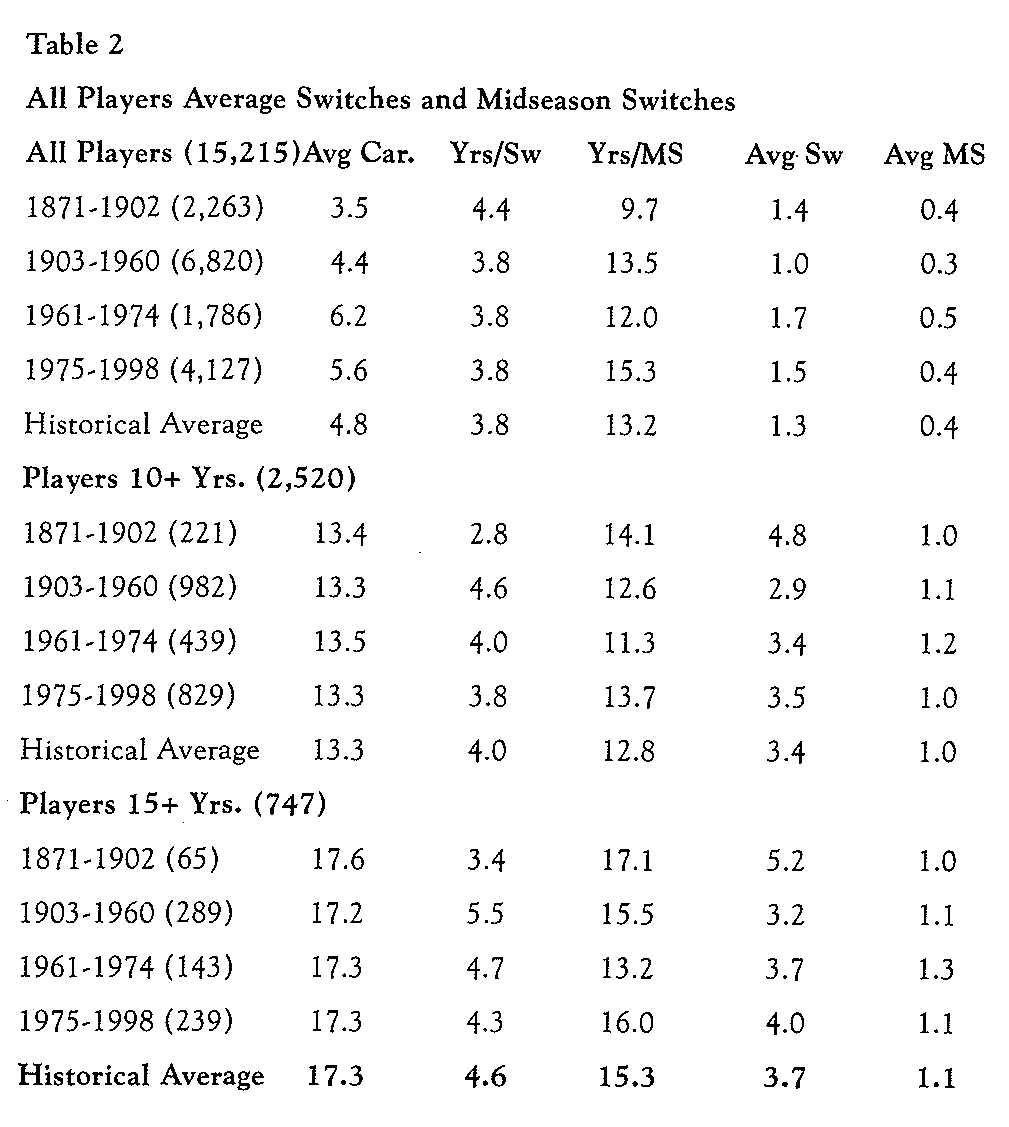

Historic averages of years played per team switch are shown in the top third of Table 2. Columns represent average career length; years played per switch; years played per midseason switch; average numbers of switches; and midseason switches per player. The numbers in parentheses represent the total number of players used to calculate the averages in that category. To explain the data: the average player who has appeared in the major leagues has a career length of 4.8 years and switched teams every 3.8 years.

Nineteenth Century players were the most mobile by far. Teams and leagues were moving into and out of existence, enticing or forcing players to move around. The average career was short and players switched teams about every 2.4 years.

The data supports the nostalgic idea that Golden Age players switched teams less frequently than modern players, but the difference isn’t that dramatic. An average player during the Golden Age switched teams every 4.4 playing years, while the average player in the Expansion era switched every 3.8 years and the average Free Agency era player switched every 3.8 years—only thirteen percent more frequently than during the Golden Age. Also, during the last quarter century, the average player made midseason switches less frequently then in any other era. Modern teams don’t move players during the season as often as those Golden Age teams did.

What about those ten-year Stars? Baseball fans reminiscing about their favorite teams never seem to remember these players leaving their favorite team. The data doesn’t support this. The middle third of Table 2 shows Stars switched teams about five percent less frequently (4.0 years vs. 3.8 years) than the complete set of major leaguers.

The bottom third of Table 2 presents the numbers for Superstars (15+ year career players). Superstars continue the trend of less frequent team switching (nineteen percent less frequent than average), but even in the Golden Age, the average Superstar switched teams more than three times during his seventeen-year career.

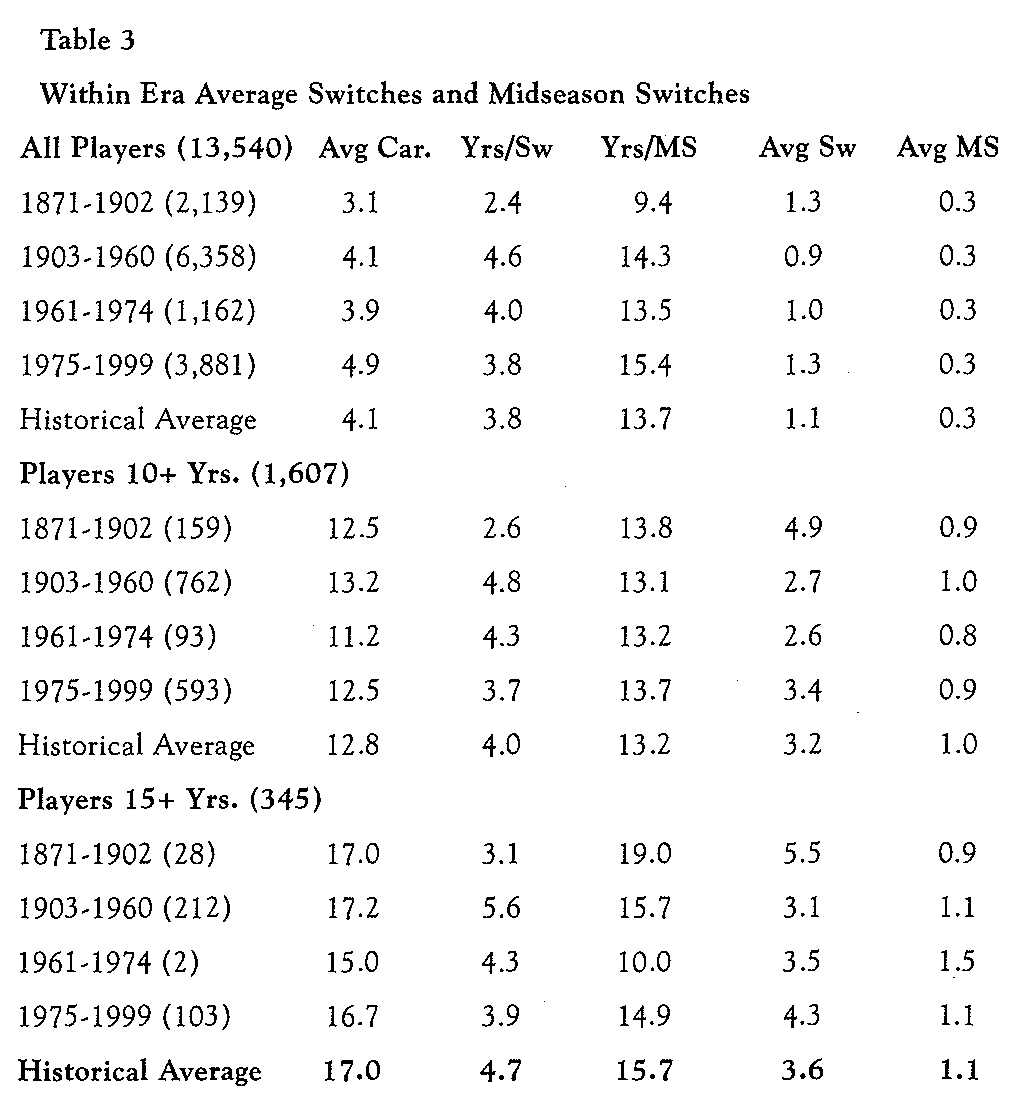

I hear you argue, “Maybe the players who crossed eras are skewing the data. Those Golden Age players who spent some time in the Nineteenth Century and others who spent time in the expansion era, are making the Golden Age years per switch go down.” To eliminate this bias I threw out all players whose careers crossed eras (such as a player whose career went from 1899-1910) and present the data in Table 3. Average career length is shorter because players with longer careers are more likely to play in two eras. Nineteenth Century players show even more mobility and Golden Age players show less. Removing the bias pushes the Golden Age Stars to 4.8 years per switch and the Golden Age Superstars to 5.6 years per switch, while Free Agency Stars and Superstars are at 3.7 and 3.9 years/switch.

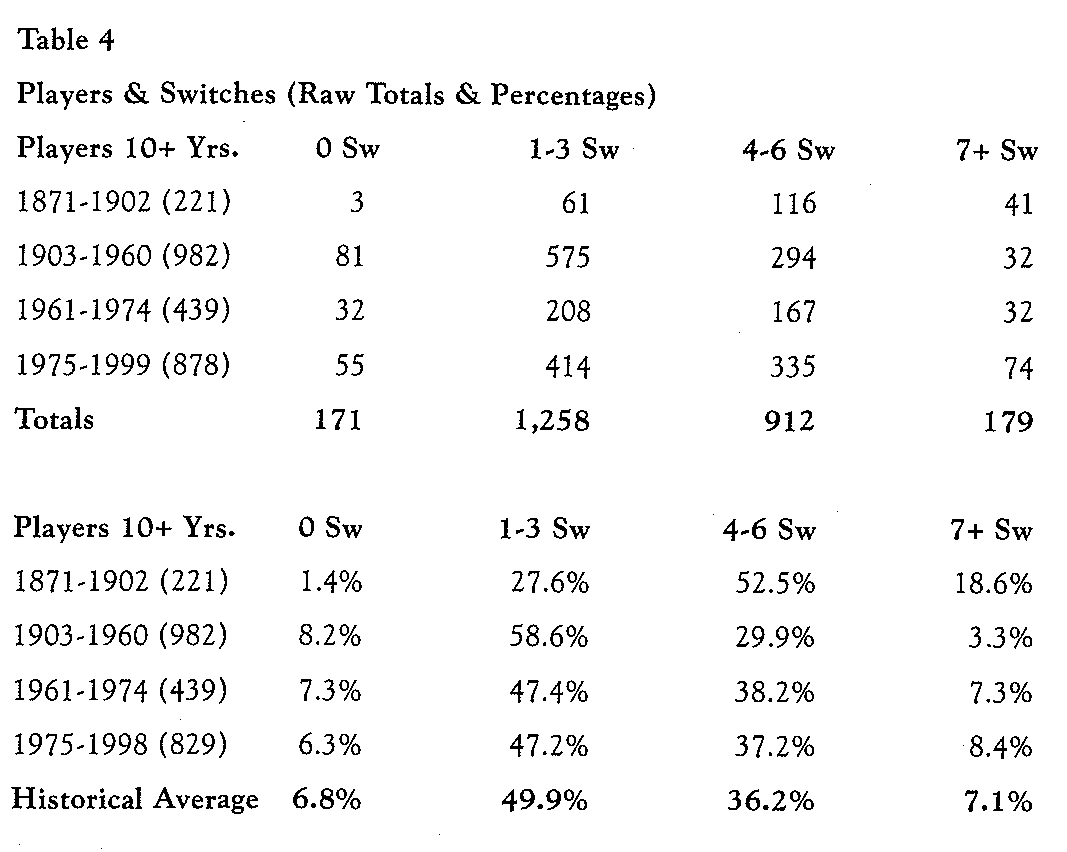

How many more players stayed with a single team during their whole career during the Golden Age then in other eras? I present data in Table 4. The top half of the table shows the raw numbers of players in each category, while the bottom half shows the percentage of players in the category. Only 1.4 percent of Nineteenth Century Stars stayed with one team for a full career, while 8.2 percent of Golden Age Stars, 7.3 percent of Expansion Stars and 6.5 percent of Free Agency Stars stayed with their teams. In other words, for every hundred Stars, about two fewer stayed with the same teams for a whole career in the modern era than in the Golden Age. One-team players have always been rare—on average, only seven of every 100 Stars stayed with one team during their entire career.

Individual Kings of Switching Teams

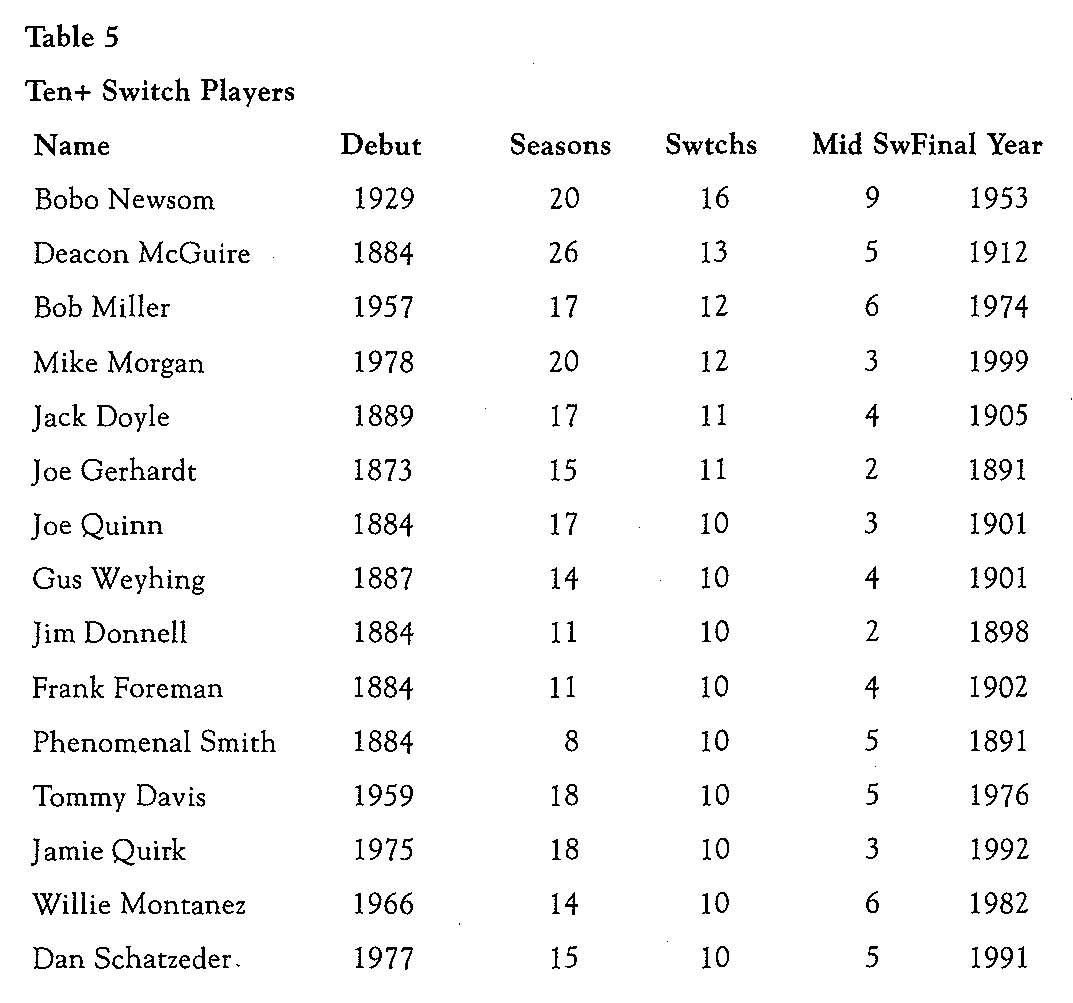

Who is that perpetual packer, that moving madman who switched teams sixteen times in a twenty-year playing career? You might think it was a player driven by modern free agency, but the king of player movement played in the Golden Age, the era when team switches were lowest. Table 5 shows all fifteen players who switched teams ten or more times during their careers. And there’s your answer: Bobo Newsom! He is the Travelin’ Man. His twenty year pitching career followed this tortured path (* denotes midseason switch): ’29 Dodgers, ’32 Cubs, ’34 Browns, ’35 Senators*, ’37 Red Sox*, ’38 Browns, ’39 Tigers*, ’42 Senators, ’42 Dodgers*, ’43 Browns*, ’43 Senators*, ’44 Athletics, ’46 Senators*, ’47 Yankees*, ’48 Giants, ’52 Senators, ’52 Athletics*. Poor Bobo; he had five different stints with the Washington Senators and three with the St. Louis Browns. His longest length of time with any club was 2-1/2 years with the Athletics (1944-46).

Of the remaining players on the list, nine of them are Nineteenth Century, two are Expansion era, and three are Free Agency era. Only one active player appears on the list—Mike Morgan. He added to his career team switches by moving from the Texas Rangers to the Arizona Diamondbacks in 2000 and he is currently tied for third all time. If he can hang on a few more years (with a couple of different teams), he’s got a shot at being the second most mobile player of all time!

There are some current players who have a real shot at getting the ten switches needed to break into this elite group (Player/Career Years/Switches): Mark Whiten/10/9, Terry Mulholland/14/9, Gregg Olson/ 13/9, Mike Maddux/15/9, Willie Blair/11/8, Dennis Cook/13/8, Doug Jones/16/8, Geronimo Berroa/ll/7, Chuck McElroy/12/8, Charlie Hayes/13/8, and Roberto Kelly/14/8.

Method

I used Sean Lahman’s baseball database files (which are available on the Internet at www.baseball1.com) as the source of my data. I ran scripts written in Perl (a shareware scripting language) to search the database files and sort and extract the data I was interested in. Then I used Excel to further sort the information and perform all the calculations.

The Perl logic used to count switches may fail when a player switches teams during midseason. The logic fails because the database information does not list a player’s career in order of teams played for (and I didn’t have the time to go back and correct the 77,000 record hitters database and the 32,000 record pitchers database!) A purely fictional example that confuses my Perl logic:

John Smith

- 1978 New York 500 AB

- 1979 St. Louis 125 AB

- 1979 New York 130 AB

- 1980 St. Louis 550 AB

This player made three switches including one midseason switch. However, in the database, the player lines may look like this:

John Smith

- 1978 New York 500 AB

- 1979 New York 130 AB

- 1979 St. Louis 125 AB

- 1980 St. Louis 550 AB

The logic would count this as one switch and one midseason switch. Another error is possible when a player switches teams midseason two years in a row. Depending on how the player’s statistic lines are listed, the logic may over- or undercount the total number of switches. I checked over 200 players who were most likely to have this kind of switch counting problem (players with multiple midseason switches) and found that undercounting and overcounting evens out, leading me to believe the data is accurate.

BRIAN FLASPOHLER is a manufacturing engineer by day and a baseball fanatic the rest of the time. His aspiration is to be the GM of the St. Louis Cardinals.