Playing Dominoes with the Called Shot: Did Violet Popovich Really Set the Whole Thing Off?

This article was written by Roberts Ehrgott

This article was published in Spring 2021 Baseball Research Journal

“Post hoc, ergo propter hoc: used in logic to describe the fallacy of thinking that a happening which follows another must be its result.” — Webster’s New World Dictionary, Second College Edition

“When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.” — The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962)1

By long-standing consensus, a 21-year-old show girl named Violet Popovich “opened the door for [Mark] Koenig to become a Cub and baseball legend” when she shot Bill Jurges of the Chicago Cubs in July 1932. Three decades later, Bill Veeck Jr., whose father ran the Cubs franchise in that era, vividly remembered the sensational impact of Popovich’s deed: “Turmoil! Sirens! Police! Doctors! Newspapermen! Scandal!”2 One effect of Popovich’s resulting notoriety has been to furnish innumerable baseball writers with an all-but-irresistible opening act for the saga that culminated in Ruth’s called shot.

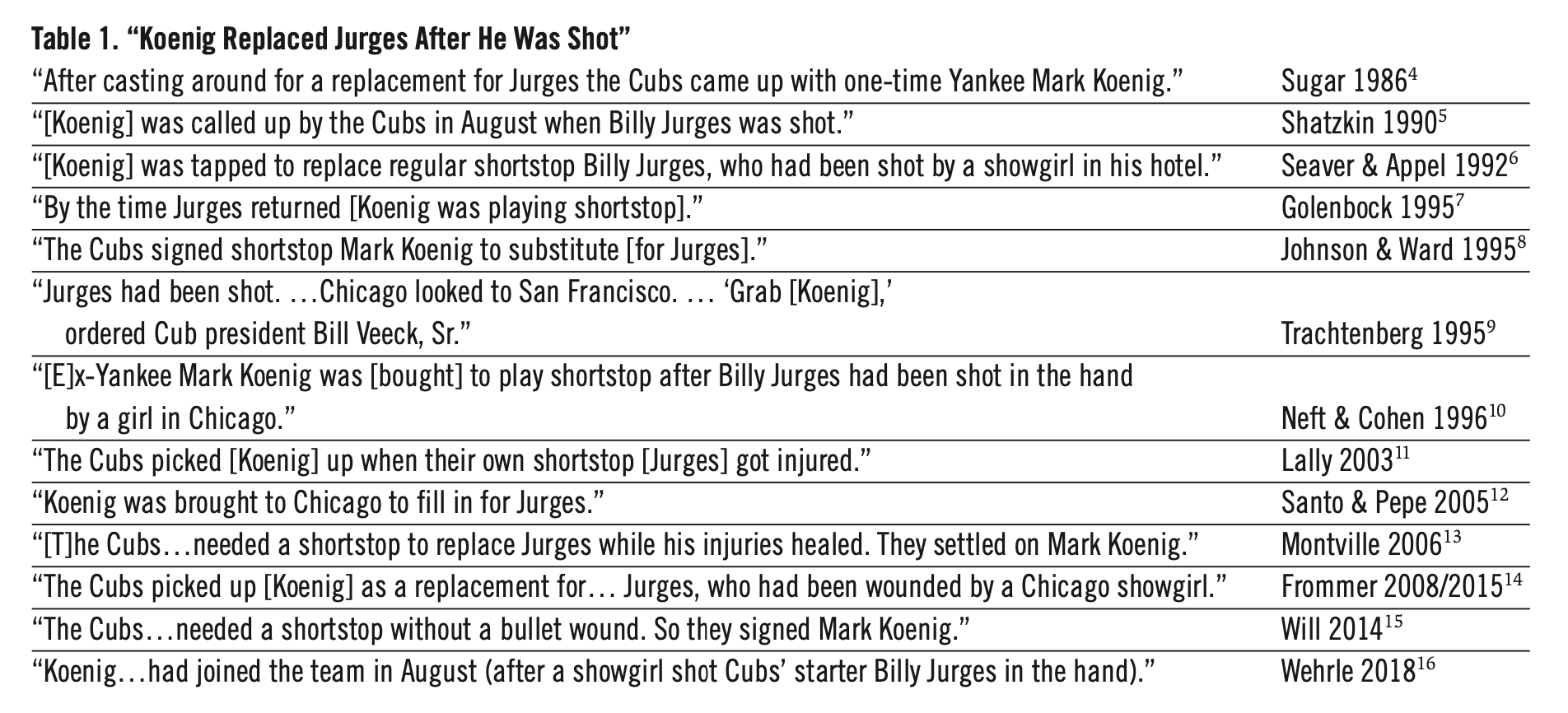

In more nuts-and-bolts fashion, the shooting invariably serves to explain Mark Koenig’s arrival in Chicago—namely, that the Cubs had to rush out and replace the wounded Jurges with another shortstop, a former Yankee whose mistreatment by the Cubs would later rouse Ruth’s (probably feigned) ire. This conventional wisdom regarding Koenig’s path to Chicago began taking shape as early as September 1932, when Murray Tynan of the New York Herald-Tribune noted that the Cubs had bought Koenig “to take care of the emergency that existed when Jurges was shot and wounded” (emphasis added).3 Since then, a legion of baseball voices, whether or not privy to Tynan’s pioneering effort, has reached near unanimity on this point (Table 1).

Table 1. “Koenig Replaced Jurges After He Was Shot”

(Click image to enlarge)

Contrary to the hypothesis of Tynan et al., however, Koenig absolutely, positively did not fill in for or replace Jurges while he recovered from his gunshot wounds. Two points bear emphasis: 1) for the entire span of Jurges’s absence in July, Koenig was gainfully employed as a shortstop in the Pacific Coast League, and 2) he did not make a start for the Cubs until six weeks after the shooting. Every inning Jurges missed while recuperating was covered by the Cubs’ incumbent starting third baseman, Woody English. You can look it up. Nonetheless, casual as well as more-attentive students of the called shot can be forgiven for believing that Koenig (who did take Jurges’s place by the second half of August) all but stepped over Jurges’s prostrate form to take up his new position at shortstop. Popovich may go unnamed, but one way or another her bullets invariably seem to be the catalyst for the called shot.

The Internet era seems to have provided renewed opportunities for mischief-making about Jurges’s and Koenig’s status at various points in summer 1932. A biography commissioned by the Society for American Baseball Research asserts that Koenig was already starting for the Cubs at “the end of July”—while the National Baseball Hall of Fame website places Koenig’s arrival in “late August.”17 Koenig’s purchase date of August 5 and arrival on August 11 render both statements inaccurate. As for Jurges, an item at Baseball-Reference.com ignores the site’s sizable databases in order to claim that the wounded Cubs shortstop missed “three weeks,” nearly a week longer than the actual 15 days.18 That’s a rounding error compared to the calculations of another site, which extends Jurges’s absence through “the end of the season”—a fivefold increase in the period involved.19

One result of the Internet era’s free-form approach to the story is to obscure the exact nature of Koenig’s acquisition—not only when but, more important, why this essential figure in the chain of events actually became a Cub. One means of investigating the problem begins with a seemingly innocuous question: If the Cubs needed Koenig urgently after Popovich shot Jurges, why did they take another month—until August 5—to acquire him?

The inclination to ignore Jurges’s and Koenig’s whereabouts during the missing month probably has more than one point of origin. Confirmation bias provides one plausible source: after all, Koenig took over after the Cubs’ original shortstop was almost killed, didn’t he? Then too, tracking the Cubs’ personnel maneuvers in July and August 1932 can prove daunting without a scorecard—and there’s the ever-present lure of adding a dash of sex and violence to one of the most memorable baseball stories ever told.

Table 2: Basic Jurges—Koenig Timeline, 1932

- July 6: Jurges shot

- July 6-23: English takes over as Cubs’ shortstop

- July 24: Jurges reinstated as starting shortstop

- August 5: Koenig acquired (Jurges continues starting)

- August 11: Koenig joins ballclub (Jurges continues starting)

- August 14-18: Koenig makes three late-inning appearances as pinch-hitter or defensive replacement (Jurges continues starting)

- August 19: Jurges sits down Koenig begins 22 consecutive starts at shortstop

Besides the date of Jurges’s shooting, few accounts of Mark Koenig’s arrival in Chicago include the dates or events listed above. (Courtesy Baseball-Reference.com)

In recent years, several efforts have substantiated the Jurges-Koenig timeline in more accurate detail. In 2013, this writer’s Mr. Wrigley’s Ball Club traced the dates of Koenig’s acquisition and his progress into the Cubs’ lineup; since then, Babe Ruth’s Called Shot: The Myth and Mystery of Baseball’s Greatest Home Run (2014); “The Show Girl and the Shortstop” (Baseball Research Journal, Fall 2016); and The Called Shot: Babe Ruth, the Chicago Cubs, and the Unforgettable Major League Season of 1932 (2020) have likewise mapped the same basic timeline.20 These efforts concur that Koenig did not appear on the field for the Cubs until mid-August 1932—a common framework that, at a minimum, rules out the long-held consensus that Koenig arrived under emergency circumstances.

That’s progress, yet both Ruth’s Called Shot and “Show Girl” afford Popovich at least some role, however tenuous, in facilitating Koenig’s arrival in Chicago. “Show Girl” in particular stresses the far-reaching, historic importance of being Violet Popovich, a woman who left no domino standing:

When Violet [Popovich] recklessly pulled the trigger in the Hotel Carlos, her bullets not only struck Jurges but had a domino effect on the Cubs, Mark Koenig, the 1932 pennant race, the division of the World Series money, and Babe Ruth’s arguable “called shot.” (“The Show Girl and the Shortstop,” page 74; emphasis added.)21

Popovich did it with her .22 on the fifth floor of the Carlos, and from there the entire strand fell cleanly to the legendary finale starring Babe Ruth, not a miss or even a wobble on the way. As in the oft-told stories of decades past, Popovich bears ultimate responsibility for the drama that continues to fire the imagination of baseball fans everywhere. Search engine optimization, Google Books, and the ubiquitous Wikipedia should ensure a long life for this version of Popovich’s impact on baseball history.22

MAKING A DIFFERENT CASE

Or maybe not. The narrative of Mr. Wrigley’s Ball Club plainly tied Koenig’s purchase on August 5 to Rogers Hornsby’s removal from the roster on August 3, and in 2020, The Called Shot confirmed that Koenig was indeed Hornsby’s direct replacement. In between those two efforts, “Show Girl” also lowered its pro-Popovich stance momentarily to concede offhandedly that there just might be something to the Hornsby-replacement case:

One could make a case that the Cubs hired Koenig to replace Rogers Hornsby…[b]ut sports-writers observed that [William] Veeck had been concerned about Jurges’s recovery. (“The Show Girl and the Shortstop,” page 71; emphasis added.)

However, no investigation ensued concerning the possibility that the Cubs “hired Koenig to replace Rogers Hornsby.” Nonetheless, if there’s any credible case that Koenig was acquired to replace Hornsby, an associated inference arises: Perhaps Popovich toppled nothing but the Jurges domino and missed the rest of the line completely. Hornsby’s woes would replace Jurges’s as the Cubs’ main incentive for obtaining Koenig.

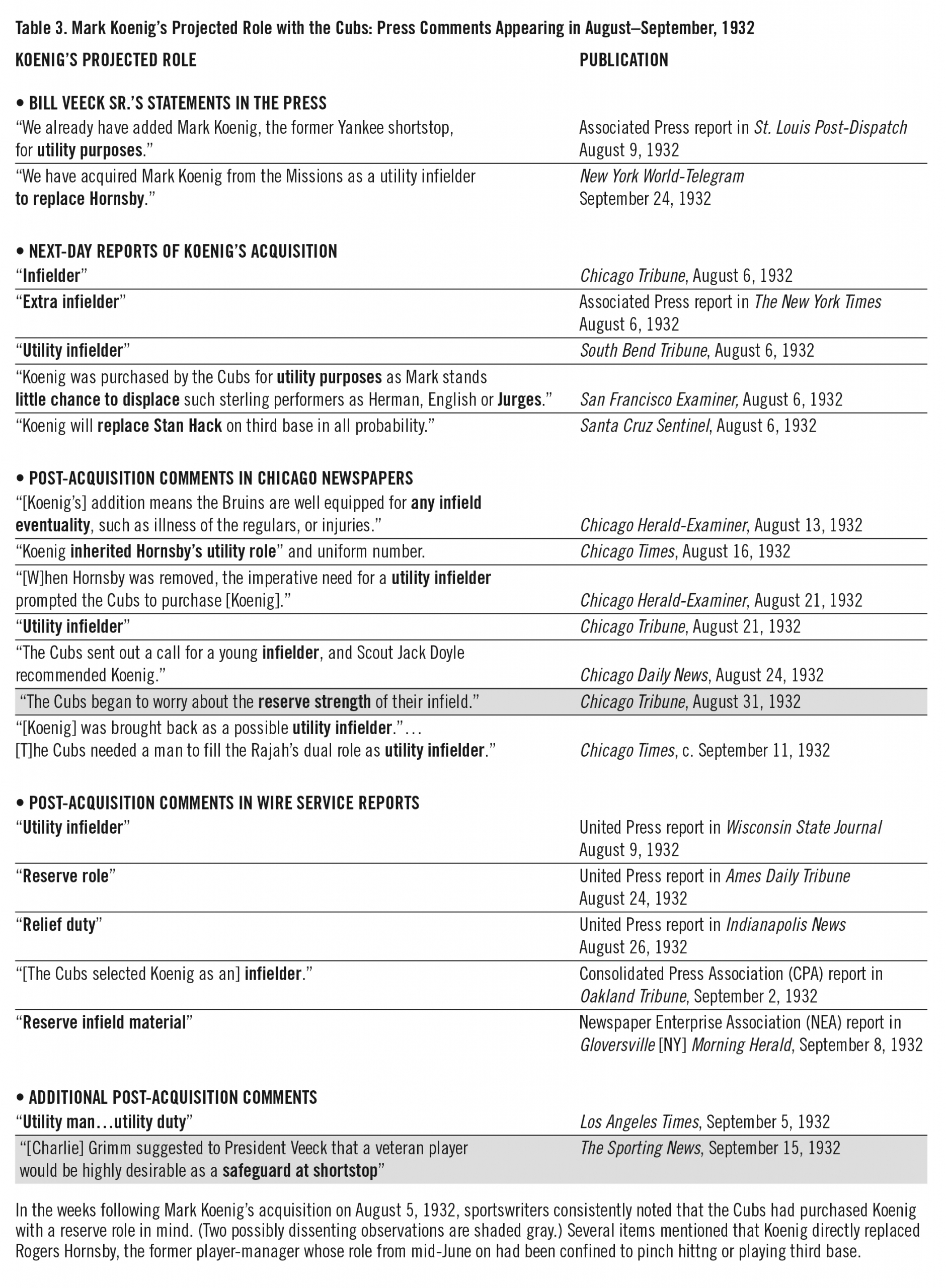

With the disposition of so many dominoes at stake in some of baseball history’s best-known outlets, it seems only sporting to look at both cases (including variant versions) in greater depth. There’s really no lack of raw material to sift through: to begin with, Bill Veeck Sr. and more than a few sportswriters (more precisely, baseball writers, a distinction that makes a difference) addressed the point repeatedly in August 1932. Such standard research tools as statistics, box scores, and specific recorded events are also readily available. (See Table 3.)

Table 3. Mark Koenig’s Projected Role with the Cubs: Press Comments Appearing in August–September 1932

(Click image to enlarge)

The idea that Koenig stepped into Rogers Hornsby’s shoes rather than Bill Jurges’s may strike many students of the game, schooled to accept Jurges as the weak link and Koenig as the solution, as downright outlandish: “Koenig replaced Jurges, didn’t he?” Well, yes and no; in a way; something like that. Perhaps a more systematic airing of the Hornsby-replaceme case and other forgotten voices from the past c begin to peel away decades of misunderstandings a establish a better platform for future discussions.

1. The Roster Opening. The process begins by revisiting the unremarkable but necessary underpinning of the Koenig transaction: that is, on August 3 the Chicago Cubs officially released a reserve infielder named Hornsby and, two business days later, purchased a Pacific Coast League infielder named Koenig. In the narrowest, most elementary sense, then, the ball club certainly did “[hire] Koenig to replace Hornsby.”

2. Hornsby: A Two-for-One Package. Merely reciting the bare bones of the roster transaction, though, does not explore additional factors that might have led to the release of this particular reserve infielder. Bad bat? Bad glove? Bad influence in the clubhouse? All of the above, yes—but more important, the evening before releasing reserve infielder Hornsby, Bill Veeck Sr. convened a press conference at Philadelphia’s Ben Franklin Hotel to announce a non-roster transaction: he had just fired infielder Hornsby’s inseparable twin, manager Rogers Hornsby.23 The managerial firing left infielder Hornsby technically still a Cub until the league offices opened the next morning, Tuesday, August 3, the official date on which infielder Hornsby is recorded as following manager Hornsby out the door. Hornsby’s vacated roster spot lay open until Thursday, August 5, when the Cubs acquired a replacement infielder, Koenig (although he did not join the club in person until the next week).

Veeck had fired an executive for cause: that was the main thing, on its face nothing to do with Jurges’s performance or anything Popovich had done, and that action also automatically involved cutting a reserve infielder. (Admittedly, the opportunity to upgrade the infield in the bargain must have been the cherry atop Veeck’s sundae.) Whether or not Veeck was simultaneously concerned about Jurges’s continued viability as a starter, the firing of Hornsby was what set things off—pushed over the next domino, if you will. The demonstrable elements of the firing and its context merit a thorough, good-faith evaluation before plunging into more-nebulous considerations. In short, it is no stretch to suggest that Veeck’s overriding concern in early August was ridding the club of manager Hornsby and that Koenig’s acquisition was simply a byproduct of the firing. If that case can be assembled coherently, the consequences of Hornsby’s behavior, not Violet Popovich’s, could be considered the driver of events toward the called shot.

3. Filling Hornsby’s Cleats. Reviewing the construction of the Cubs roster at the time of the firing provides one means of evaluating what Veeck’s plans for Koenig might have been. Koenig, at least technically, simply filled the void that had been created by terminating the player portion of a player-manager arrangement: so far, so good, but did the Cubs president have any expanded role in mind for the new man beyond merely inheriting Hornsby’s limited playing duties—such as, say, taking over shortstopping duties for a recently injured player?

A fair question—but at the time, Veeck explained that Koenig had been acquired for “utility purposes” and as a “utility infielder,” both terms closely matching the common understanding of Hornsby’s previous role on the squad.24 In the following weeks, describing Koenig’s role in Veeck’s terms (not to mention a dearth of references to any faltering or inadequacy on Jurges’s part) was echoed in a score of comments from more than a dozen contemporary writers, several of them assigned to cover the Cubs daily. (It was also noted that Koenig received Hornsby’s old jersey number.) Intimations that the former Yankee might have been brought in with another role in mind began to appear only weeks later, after Koenig had established himself as the new star of the Cubs’ pennant drive.

4. The Shortage of Shortstops. Why did Veeck settle on shortstop Koenig in particular? No doubt, Koenig’s remarkable comeback in the Pacific Coast League had caught his eye, and it’s been suggested that Jurges’s health was still in question. But were there any demonstrable reasons beyond concern about Jurges to focus on acquiring another shortstop? Examining the available records can shed additional light here as well.

In the immediate aftermath of the shooting, Woody English had manned shortstop for more than two weeks with no realistic backup should he sprain a finger. It was by no means the first time in 1932 that the Cubs found themselves in such a predicament: both Jurges and English had already spent extended stretches of the season soloing at short without a net when one or the other was injured. Aggravating the situation, English was the team’s regular starting third baseman: each time he had to slide over to short, the Cubs were forced to call upon a couple of less than satisfactory reserves (one named Hornsby) at third. In sum, most fantasy-baseball managers would appraise the left side of the 1932 Cubs infield as in urgent need of an upgrade. It’s not unreasonable to suggest that this long-festering problem was Veeck’s primary concern as he mulled over a potential replacement for infielder Hornsby, all the more so if evidence of Jurges’s unsatisfactory performance should prove less than convincing.

5. Jurges’s Condition. Was Jurges’s performance during his comeback unsatisfactory? The same record book that establishes the precise dates of his absence also demonstrates that in the month after Jurges returned to action July 22, he outwardly displayed the stamina of a healthy, fully recovered ballplayer: starting 26 consecutive games, departing only occasionally for late-inning pinch hitters, and playing anywhere between 14 and 19 innings on eight different days (six double headers plus two extra-inning games). None of that seems to raise the kind of red flags that ordinarily trigger a search for a healthier replacement. Nor does scrutinizing such benchmarks as batting average and various fielding metrics reveal measurable declines in Jurges’s performance during his comeback. Jurges maintained his starting role without a pause through a historic, wrenching change of managers, soon followed by the acquisition and arrival of the better-known and much more experienced Koenig.

6. The unexplored country. The Cubs’ pace in acquiring and using Koenig is another factor in evaluating the narrative that Jurges’s incapacity or diminished performance provoked Koenig’s acquisition. The weeks that elapsed between the shooting and Koenig’s purchase were followed by a further two unhurried weeks of arrival and deployment. Upon joining the Cubs on August 11, Koenig was immediately consigned to the bench; not until August 19—six weeks after the shooting, nearly a month after Jurges returned to the lineup, and more than a week after Koenig’s arrival—did the signal suddenly switch to “go” for the ex-Yankee. In an abrupt reversal that began on that date, the Cubs quickly made Koenig their exclusive starting shortstop and just as swiftly demoted Jurges to the role of reserve infielder previously occupied by Hornsby and Koenig himself.

The reasons the Cubs chose one particular day in mid-August for their about-face regarding Koenig are among the most intriguing and problematic factors in the Hornsby-replacement case, yet that day has been decidedly underreported in nearly all quarters, even though you can look that up, too. To believe the reports of the Chicago dailies—two of them appearing the next morning—Koenig’s first start on August 19 amounted to an unanticipated happenstance, not the fulfillment of a front-office plan.25

The idea that Mark Koenig owed his opportunity to Violet Popovich began to gain traction in the press only after Koenig had established himself as the Cubs’ regular shortstop. The sources for such reassessments, however, tend to be unclear, and details that can be confirmed are scarce or fuzzy—even down to what the exact problem with Jurges or shortstop was supposed to have been. Beginning with that shaky foundation, the accounts often contradicted one another, forgot to remember what their own papers had reported about the Koenig transaction, and avoided addressing the 14-day gap between Koenig’s purchase and his first start.

Those are sizable, though not insurmountable, hurdles in the way of the idea that the Cubs needed Koenig because Violet Popovich hurt Bill Jurges. To be sure, the ex post facto accounts, if shy on verifiable details, originated with veteran, well-situated writers: the two most congruent versions evidently originated with the sports desk of none other than the Chicago Tribune.26 That itself is a clue worthy of its own full airing as the main portal to link Violet Popovich and Mark Koenig.

DOES IT MATTER?

For reasons large and small, scrutinizing Popovich’s relevance to the called shot impacts more than quibbles and gotchas over fine points of particular comments, or guesswork about the Cubs’ personnel decisions.

The Credibly Shrinking Violet. To begin with, if credible evidence lessening or removing Popovich’s effect on the Koenig domino gains a foothold in the literature, her role in the big story of 1932 shrinks to that of a mere bystander whose misadventures affected the field of play only briefly; she becomes a meddlesome if dangerous hanger-on whose legacy ultimately differs little from that of another well-known gun-toting Chicago woman, Ruth Ann Steinhagen.27

Who Pushed Over the First Domino, and When? Subtracting Popovich from the equation would also shorten the line of dominoes, which would not begin toppling toward the called shot until a different and later point. A brand-new, unwitting author of the Cubs’ eventual debacle would take Popovich’s place at the head of the downsized line: Rogers Hornsby, the man who provoked Bill Veeck into taking drastic action.

What Was the Plan? Mischaracterizing or exaggerating Popovich’s continued responsibility for Jurges’s condition also tends to equate Koenig’s acquisition with the modern era’s late-summer roster moves designed to put contenders over the top. But if all the 1932 Cubs originally intended was to shore up their bench— and as suggested earlier, credible evidence exists to support that case—Koenig’s acquisition originally amounted to no more than adding a journeyman.

Whether or not the eventual World Series controversy had anything to do with Popovich, it’s still undeniably true that Koenig starred at shortstop, the Cubs halved his Series share, the feud commenced, and Ruth eventually turned Wrigley Field into his personal playground. Students of the called shot remain hopelessly divided on the question of Ruth’s gesture to center field on October 1, yet on either side of the great divide it remains a truism that the show opened on July 6, with Popovich setting the cascade of dominoes on its way. Generations of insistent repetition in that regard have grafted the show girl’s sad tale into the permanent narrative.

Should it develop that there’s no Popovich to kick around anymore, the lodestar that the young woman “opened the door for Koenig to become a Cub and baseball legend” will no longer provide a convenient, safe shortcut through the dog days of the 1932 pennant race and the fabled postseason that followed. Before diving deeper into a swirl of contrarian evidence, counterevidence, and rebuttals, a couple of preliminary spoilers may be in order: Mark Koenig’s famous starring role in the pennant race did not unfold in the manner repeated by generations of writers and fans, and as a result, the importance of being Violet Popovich just may have been oversold.

ROBERTS EHRGOTT is the author of Mr. Wrigley’s Ball Club: Chicago and the Cubs during the Jazz Age (University of Nebraska Press, 2013). The Philip G. Spitzer Literary Agency served as the representative for the book, which placed as first runner-up in voting for the 2014 Casey Award in baseball literature. Ehrgott’s career in baseball history began in the 1980s, when he reintroduced Indianapolis residents to a virtually forgotten native son, Hall of Famer Chuck Klein; as a result, the city dedicated a municipal sports complex in Klein’s name. Away from squinting at microfilm and online baseball archives, Ehrgott has edited publications as diverse as The Saturday Evening Post and the academic journal Educational Horizons, founded in 1910 to serve women in education.

Notes

1. Second epigraph (“When the legend becomes fact…”): Carleton Young, playing a newspaper editor in the motion picture The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962), uttered these words near the end of the film. Director: John Ford. Screenplay: James Warner Bellah and Willis Goldbeck.

2. Bill Veeck, Jr., with Ed Linn, The Hustler’s Handbook (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1965), 164.

3. Murray Tynan, “Koenig Comes Back to Dazzle Those Who Counted Him Done,” New York Herald-Tribune, September 4, 1932.

4. Bert Randolph Sugar, Baseball’s 50 Greatest Games (New York: Exeter Books, 1986), 70.

5. Mike Shatzkin, The Ballplayers: Baseball’s Ultimate Biographical Reference (New York: Arbor House Publishing, 1990), 581.

6. Tom Seaver and Martin Appel, Great Moments in Baseball (New York: Carol Publishing Group, 1992), 102.

7. Peter Golenbock, Wrigleyville: A Magical History Tour of the Chicago Cubs (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1996), 232.

8. Lloyd Johnson and Brenda Ward, Who’s Who in Baseball History (New York: Barnes & Noble Books, 1994), 226.

9. Leo Trachtenberg, The Wonder Team: The True Story of the Incomparable 1927New York Yankees (Bowling Green, OH: Bowling Green State University Popular Press, 1995), 17.

10. David S. Neft and Richard M. Cohen, The Sports Encyclopedia: Baseball, 16th edition (New York: St. Martin’s, 1996), 172. This wording from the long-running annual series can be found on Google Books; it also appears in this writer’s well-thumbed hard-copy version of the 16th edition (1996). However, the 1981 edition, also present on Google Books as of February 23, 2021, says only: “A sore spot was eased late in the year when ex-Yankee Mark Koenig was brought [sic] to play shortstop,” without the additional “after Billy Jurges had been shot . . .” phrasing. Word searches in the 1981 edition for “Jurges” produced only a table with his batting statistics. Evidently, sometime between 1981 and 1996, one of the authors (Neft died in 1991) must have come across some plausible secondary information and added it to the annual’s ongoing 1932 season recap.

11. Frank Crosetti, quoted in Richard Lally, Bombers: An Oral History of the New York Yankees (New York: Three Rivers Press, 2003), 4. Crosetti’s statement is interesting on several accounts. Although Crosetti was a starter for the 1932 Yankees throughout the season and the World Series, what did he know, and when did he know it? A couple of assumptions: a) everyone in professional baseball had heard about Jurges’s shooting on July 6, but b) Koenig’s acquisition on August 5 necessarily received much less attention. However, c) surely someone on the Yankees had been following their former teammate’s remarkable comeback in the PC.L. and his re-entry into the major leagues. The Yankees, then, d) must have known at the start of the Series that the Cubs had not picked up Koenig to replace the injured Jurges. Perhaps the overwhelming nature of the developing Cubs-Yankees feud and its famous consequences more or less blurred this less-critical distinction from their consciousness. Alternatively, the Yankees possessed closely guarded inside information about the Koenig transaction—or more likely, with the passage of decades and the inexorable pull of “Koenig at shortstop, replacing the injured Jurges” (perhaps aided by some less-than-thorough baseball history methodology in the pre-Seymour era), Crosetti came to believe a point that might have struck him as absurd in August 1932.

12. Ron Santo and Phil Pepe, Few and Chosen: Defining Cubs Greatness Across the Eras (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2005), 46.

13. Leigh Montville, The Big Bam: The Life and Times of Babe Ruth (New York: Doubleday, 2006), 309.

14. Harvey Frommer, Five O’Clock Lightning: Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, and the Greatest Baseball Team in History, the 1927 New York Yankees (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2008), 227.

15. George F. Will, A Nice Little Place on the North Side: Wrigley Field at One Hundred (New York: Crown Archetype, 2014), 57.

16. Edmund F. Wehrle, Breaking Babe Ruth: Baseball’s Campaign Against Its Biggest Star (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2018), 199.

17. “End of July”: Paul Geisler Jr., “Billy Jurges,” accessed February 23, 2021, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/aada6293. “Late August”: Scott Pitoniak, “He Called It,” accessed February 23, 2021, https://baseballhall.org/discover-more/stories/baseball-history/ruth-called-it.

18. Anonymous, “Billy Jurges,” accessed February 23, 2021, https://www.baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Billy_Jurges.

19. Anonymous, “1932: The So-Called Shot,” accessed February 23, 2021, http://www.thisgreatgame.com/1932-baseball-history.html.

20. Roberts Ehrgott, Mr. Wrigley’s Ball Club: Chicago and the Cubs during the Jazz Age (University of Nebraska Press, 2013); Ed Sherman, Babe Ruth’s Called Shot: The Myth and Mystery of Baseball’s Greatest Home Run (Guilford, CT: Lyons Press, 2014); Jack Bales, “The Show Girl and the Shortstop” (Baseball Research Journal 45, no. 2, Winter 2016); Thomas Wolf, The Called Shot: Babe Ruth, the Chicago Cubs, and the Unforgettable Major League Season of 1932 (University of Nebraska Press, 2020).

21. Although the author’s name appears on page 74 as providing assistance with the article, the quoted passages from pages 71 and 74 of “Show Girl” do not represent any input he provided in the course of several prepublication email exchanges.

22. On January 30, 2019, such conclusions dominated the first pages of Google, DuckDuckGo, and StartPage after the phrase “Jurges Popovich” was entered into each search engine.

23. See Mr. Wrigley’s Ball Club, 303-304. According to various newspaper accounts of the time, Hornsby had two contracts with the Cubs—one as a manager and one as a player.

24. “Utility purposes”: Associated Press report in St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 9, 1932. “Utility infielder”: Veeck as quoted by Dan Daniel in “Dan’s Series Dope,” New York World-Telegram, September 24, 1932.

25. For instance, an unsigned item in the August 20 Chicago Tribune reported that Jurges had taken the bench due to “a misery in his stomach [emphasis added], but there have been complications involving his batting average.” Hence, the city’s major daily reported that Jurges was out sick, but the back half of the item also illustrates the problems involved in evaluating other possibilities involving Jurges’s benching: his batting average had actually risen a tick since he was shot six weeks earlier, and he was also, for him, on something of a batting tear—7 hits in his last 21 plate appearances, a walk-off RBI single a few days earlier, and the next day, a 19-inning, 2-for-7 stint along with one of the Cubs’ three RBI. The author hopes to publish a longer monograph that attempts to demonstrate just how elusive and murky the Popovich-Jurges-Koenig scenario continues to be, even after removing the most-glaring misconceptions—an area that, barring the discovery of some rock-solid primary source, is probably no more likely to reach final resolution than the called shot itself.

26. Arch Ward, “Talking It Over,” Chicago Tribune, August 31, 1932, 17; “Series May Cast Old Pals in Role of Foes” (no byline), The Sporting News, September 15, 1932, 3. The author’s understanding is that Tribune reporters contributed the Cubs (and White Sox) reports in The Sporting News. Because Edward Burns covered the Cubs for the Tribune during the second half of the 1932 season, he would thus be the presumed writer of “Series May Cast Old Pals.” As stressed in the current article, there is substantial reason to question whether either the Tribune or The Sporting News piece can be regarded as definitive or—particularly in Ward’s case—accurate.

27. In June 1949, Steinhagen, like the Popovich of 1932 a young, single Chicagoan, shot Eddie Waitkus of the Philadelphia Phillies in a Chicago hotel room. Steinhagen had become infatuated with her future victim during his previous tour of duty with the Cubs. Waitkus’s injuries caused him to miss the last 3 1/2 months of the season. (One measure of the relative notoriety of these would-be femmes fatale: an Internet search for “Violet Popovich” on February 12, 2019, resulted in 271,000 Google hits, compared to 65,000 for “Ruth Ann Steinhagen.” Evidently, the grip of the Bambino, his called shot, and possible related events has maintained a greater hold on the public imagination than a well-regarded novel that was adapted as a successful and memorable movie.)