Prelude to the Formation of the American Association

This article was written by Brock Helander

This article was published in The National Pastime: From Swampoodle to South Philly (Philadelphia, 2013)

Six of the eight most populous cities in the United States were not represented in the National League for the baseball season of 1881. New York, Philadelphia, Brooklyn, St. Louis, Baltimore, and Cincinnati were not members of the League, which included only two charter members (Chicago and Boston) and teams from the smaller cities of Cleveland, Buffalo, Detroit, Providence, Worcester, and Troy. Nonetheless, independent teams throughout the United States enjoyed both popularity and financial success and the need for a second major league became obvious. The prelude to the formation of the American Association in November 1881 is herein examined in the context of the September Western tours of the interregnum Atlantics and Athletics and the principals supposedly involved in a preliminary meeting in October.

The Atlantics of Brooklyn was a venerated name in the early history of baseball. The club, organized on August 14, 1855,1 was a member of the National Association of Base Ball Players (NABBP) from 1858 to 1870, playing professionally in 1869 and 1870.2 An Atlantic club was also a member of the National Association of Professional Base Ball Players (NAPBBP) from 1872 through September 1875 when it disbanded. An entirely new Atlantic nine formed to play on the Capitoline Grounds in April 1878, but in less than two weeks, most of the team, including Candy Cummings and Bill Barnie, were spirited away to New Haven by Ben Douglas for his International Association team.3 Another Atlantic team, initially attributed to Barnie, was organized in April 1879 by manager Jack Chapman, but by the end of May he had left to manage an International Association team in Holyoke.4 Eventually, Barnie, in April 1881, organized yet another Atlantic team to play at the Union Grounds, joining the short-lived Eastern Championship Association.5

The Athletics of Philadelphia originally formed as a town ball club on May 31, 1859, and reorganized as a base ball club on April 7, 1860.6 The Athletics were members of the NABBP from 1861 to 1870, playing professionally in 1869 and 1870, in the NAPBBP from 1871 to 1875, and in the National League of Professional Base Ball Clubs in 1876.7 After being expelled from the NL for failing to complete their final Western trip, an independent Athletics team organized in 1877 as a stock company under new president Charles H. Downing and joined the League Alliance in order to protect the club from player raids by National League clubs.8 The Athletics reorganized for 1878 under manager Alfred H. Wright, utilizing 40 players en route to a 45–16–1 record as an independent team.9 Yet another Athletic club formed in 1879 under William W. Hincken and reorganized for 1880 with William Sharsig as president.10 With Sharsig as nominal president through 1883, the 1881 Athletics joined the Eastern Championship Association under manager Horace Phillips.11

The Westerners

O.P. Caylor and Justus Thorner. Oliver Perry Caylor, born in Dayton, Ohio, on December 14, 1849, was admitted to the bar in Cincinnati in 1872, but opted for a journalistic career with the Cincinnati Enquirer in November 1874. Ascending to the position of sports editor, Caylor garnered a reputation for his clever, humorous, and often acerbic reporting.12

Justus Thorner, a manager for local breweries, was president of the semi-professional Star Club of Cincinnati in 1879.13 After President J. Wayne Neff of the rival Cincinnati National League club announced that his players would be released on October 1, 1879, and forwarded the club’s resignation from the League, Thorner met with National League president William Hulbert in Chicago, formally applying for membership in the League.14 At the annual meeting of the National League, held in December in Buffalo, New York, rather than Cincinnati, as originally scheduled, the organization’s Board of Directors admitted the Star Club to membership and Thorner was elected to the Board of Directors.15 On December 22, the stockholders of the new Cincinnati club elected directors and officers, including Thorner as president.16 Thorner and Caylor represented the club at a special meeting of the National League on February 26, 1880, in Rochester, New York.17

In early July, the directors of the club requested and received the resignation of Thorner as president, and W.C. Kennett represented Cincinnati at the special meeting of the League on October 4 at Rochester, New York. Henry Root, president of the Providence club, proposed an amendment to the League constitution that would prohibit the sale of alcoholic beverages on club grounds and the use of such grounds for Sunday baseball, both of which the Cincinnati club depended on. All except Kennett pledged to vote in favor of the amendment at the League’s December meeting.18 On October 6, the membership of Cincinnati in the League was declared vacant.19

By late April 1881, a new baseball club had been formed in Cincinnati. It began play in St. Louis May 28, with Caylor reporting on the games.20 Only days earlier, the leasehold and grounds of the Cincinnati club had been sold to “four prominent Cincinnati gentlemen,” later revealed to be Caylor, Thorner, Victor Long, and John Price.21 Caylor resigned his position with the Cincinnati Enquirer in August, ostensibly to return to the practice of law. Nonetheless, Caylor soon joined the staff of the Cincinnati Commercial Gazette.22

Alfred Spink. Alfred Henry Spink was born on August 24, 1854, in Quebec, Canada. Moving with his family to Chicago after the Civil War, he moved in 1875 to St. Louis, Missouri, where his brother Billy was sports editor for the St. Louis Globe-Democrat. Soon thereafter, Alfred began covering baseball for the Missouri Republican, subsequently becoming sporting editor for a number of St. Louis newspapers, including the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Becoming acquainted with saloon owner Chris Von der Ahe, vice president of the Grand Avenue Base Ball Club in 1877, Alfred and Billy began organizing semi-professional baseball teams in 1878. Their 1879 team, called the Browns or Brown Stockings, won 20 of 21 games.23

Because dates and sources conflict, the baseball situation in St. Louis becomes convoluted beginning in 1880. Most likely Al Spink, with veteran player Ned Cuthbert, organized the co-operative St. Louis Browns and, with a number of local men, organized the St. Louis Base Ball Association.24 In May, another team using the Brown Stockings name was organized under the presidency of Chris Von der Ahe.25 By the end of May, the St. Louis Globe-Democrat was referring to Cuthbert’s club as the Reds or Red Stockings and Von der Ahe’s club as the Browns or Brown Stockings.26

In October, Von der Ahe and others formed the Sportsman’s Park and Club Association, with Spink as secretary, and secured the lease on Grand Avenue Park, which was to be enlarged and improved and would be known as Sportsman’s Park.27 In March 1881 the Sportsman’s Park and Club Association incorporated.28 The Brown Stockings were organized in April, formally opening Sportsman’s Park on May 22 with a defeat of the rival St. Louis Red Stockings before at least 2,500 people.29 Five of the Browns players had been members of the Reds in 1880, most significantly Bill and Jack Gleason.

The Easterners

Horace B. Phillips. Horace B. Phillips was born in Salem, Ohio, most likely on May 14, 1853, yet earlier reported as May 20, 1856.30 Growing up in Philadelphia, he began his baseball playing career with local amateur teams in 1870. Securing his first professional engagement with the Philadelphia club in 1877, Phillips soon succeeded Fergy Malone as manager. A baseball vagabond in his early career, he subsequently played for and managed clubs in Hornellsville and Syracuse, New York, before managing clubs in Troy and Baltimore in 1879 and Baltimore and Rochester, New York in 1880. Returning to Philadelphia in 1881, Phillips was reported managing the independent professional Athletics team by the end of May.31

Billy Barnie. William Harrison Barnie, born in New York City on January 26, 1853, began playing for amateur baseball clubs in Brooklyn at an early age, manning the Nassau club for three years beginning in 1870 and the Atlantics of Brooklyn in 1873. He initiated his professional career with Hartford in 1874, playing with the Buckeye club of Columbus, Ohio, in 1876 and managing it in 1877. Barnie played for and managed the Buffalo club later in 1877 and was a member of the Atlantics team that moved to New Haven, then Hartford, in 1878. After playing for the Knickerbocker club of San Francisco in 1879 and 1880, he returned to Brooklyn and organized an independent professional Atlantics club in April 1881, becoming its secretary.32

The Pittsburghers

Al Pratt. Albert G. Pratt was born on November 19, 1848, in Allegheny, Pennsylvania, and joined the Union Army at the age of 15, serving in the infantry. He helped form the Enterprise Base Ball Club of Pittsburgh in 1866 and later joined the Allegheny Club. After a season with the Riverside Club of Portsmouth, Ohio, Pratt pitched for the famous Forest City Club of Cleveland from 1869 to 1872. He returned to Pittsburgh and pitched for the Enterprise club from 1873 to 1875 and played with the Xantha club from 1876 to 1879.33 Pratt then served as a National League umpire in 1879 and substitute umpire in 1880.34

H.D. “Denny” McKnight. Harmar Denny McKnight was born in 1847 in Pittsburgh and graduated from Lafayette College in 1869. Pursuing a business career, he became director of an iron manufacturing company in 1876. That year he helped organize the independent Allegheny baseball club, serving as one of its directors. The following year McKnight was instrumental in the formation of the International Association of Professional Base Ball Players and served as its president after Candy Cummings resigned. However, the Allegheny club disbanded in June 1878.35

Out West

As Alfred Spink stated in his book The National Game: “I wrote to O.P. Caylor, then the sporting editor of the Cincinnati Enquirer and I suggested to him the idea of picking up all that was left in Cincinnati of the old professional players, forming them into a nine, christening them the Cincinnati Reds and bringing them here to play three games on a Saturday, Sunday and Monday with my reconstructed St Louis Browns.” Spink continued: “Mr. Caylor, accepting my suggestion, quickly got together a team of semi-professionals, called it the Cincinnati Reds and brought it here to help open the reconstructed St. Louis baseball grounds, which my brother William had named Sportsman’s Park.”36 Their Sunday, May 29 game, won by the Browns 16–2, drew an estimated four thousand spectators, making it a substantial success.37

More Spink: “The Dubuques, the Cincinnati Reds and the Chicago prairie teams came to St. Louis and the games drew such crowds, especially on Sundays, that soon news of the prosperity wave reached the East.”38 Among the well-attended Sunday games in St. Louis were the July 3 game against the Eckfords of Chicago (4,000), the July 17 game against Dubuque (nearly 5,000), and the August 14 game against the Buckeyes of Cincinnati (over 5,000).39

Spink: “Later I wrote to Horace B. Phillips, then managing the Athletics of Philadelphia, and to William Barnie, then operating the Atlantics of Brooklyn. Both the Athletics and the Atlantics were free lances outside the pale of the National League and were willing to come all the way to St. Louis to meet the St. Louis Browns for a division of the gate receipts.”40 Barnie later reminisced: “Horace Phillips of the Athletics and myself then formed the idea of organizing a big league. We learned through the papers that large audiences were being attracted by base ball teams in Cincinnati, Louisville and St. Louis and began negotiating for a trip to those cities. The Western clubs guaranteed us more than enough to pay our expenses on the round trip. We accepted and both the Atlantics and Athletics took the journey.”41

In late July, Cincinnati applied for admission to the National League for 1882.42 In mid-August Phillips was reported to be in Chicago, meeting with National League President William Hulbert to request admission for the Athletics, who withdrew the application within two weeks and released Phillips only days before the October meeting.43

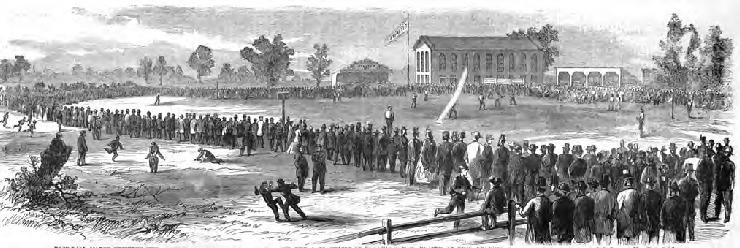

The Atlantics of Brooklyn and the Athletics of Philadelphia formed one of the most intense rivalries during baseball’s pioneer era. This graphic depicts a match between the clubs at Philadelphia from 1865.

The Tours

The Athletics were the first to embark on a Western tour. On September 2 in Louisville the Athletics defeated the Eclipse of Louisville, with manager Phillips playing in center field. The next day in St. Louis, the St. Louis Browns beat the Athletics. On Sunday, September 4, before an astounding 7,000 fans, the Browns proved victorious. The final game in St. Louis September 5 was won by the Athletics. Returning to Louisville, the Athletics on September 8 lost to the Eclipse morning and afternoon games. On September 9 the Athletics defeated an ad hoc team in Cincinnati.44 According to one source, Thorner found out about the game and joined the crowd of 200 in the eighth inning.45 Later, in a letter to the Cincinnati Commercial Gazette, Phillips stated that he did indeed consult Caylor on this occasion.46 The next day on their way home, the Athletics lost to the Detroit National League club in Allegheny (near Pittsburgh) before 2,000 fans, with Al Pratt serving as umpire.47

After defeating the Athletics in Philadelphia on September 14 and 15, the Atlantics arrived in Louisville on September 17 and bested the Eclipse. The next day the Eclipse prevailed and again on September 19. On September 22 the Eclipse again won. Heading to St. Louis, the Atlantics prevailed over the Browns on September 24, scoring the winning run in the top of the ninth. On Sunday, September 25, the Browns were victorious. The game scheduled for September 26 was canceled due to the death of President Garfield. The third game, postponed due to rain, was played September 28, but was suspended due to darkness with the score Atlantics 13, Browns 12. The following day, the Atlantics beat the St. Louis Reds by the identical score. As the St. Louis Browns devolved into chaos at the beginning of October, the Atlantics defeated one of the clubs claiming the Browns’ name on October 9. On their way home to Brooklyn, the Atlantics stopped over in Philadelphia and defeated the Athletics.48

Phillips, upon his return to Philadelphia, stated that “the movement [to form a new league] was meeting with great favor in St. Louis, Pittsburgh, Louisville, and Cincinnati….”49 The Cincinnati Enquirer, probably Frank Wright, agreed: “The outlook is very promising. (A) scheme is on foot to organize a new association, to include St. Louis, Louisville, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Washington, Cincinnati, Pittsburgh, and New York. Already the proposition has been entertained in St. Louis and Louisville, and a meeting will be held in Pittsburgh, October 10, to perfect arrangements.”50 The Clipper reported: “THE NEW ASSOCIATION will hold a meeting Oct. 10 in Pittsburgh. Clubs who intend sending representatives will please communicate with H.B. Phillips, Great Western Hotel, Philadelphia Pa.”51

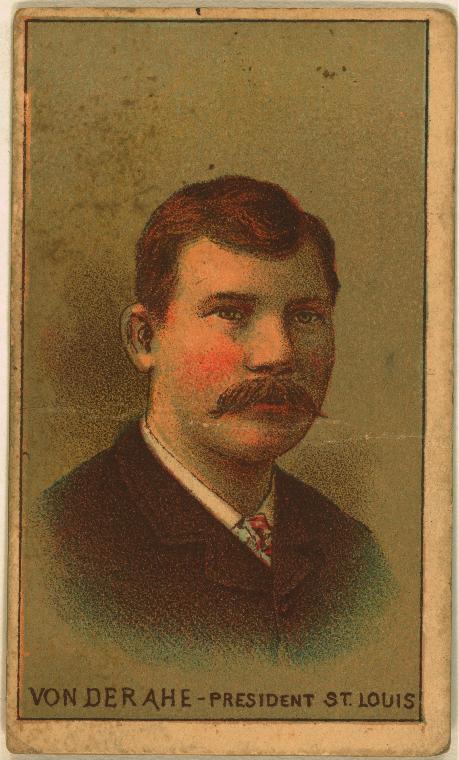

One of the most enigmatic figures of nineteenth-century baseball, president Chris Von der Ahe led the St. Louis Browns to four consecutive pennants during the ten-year existence of the American Association.

The Meetings

Who was actually at the meeting is a matter of conjecture. Justus Thorner’s 1889 account of the meeting erroneously stated that Phillips was there. Later, Caylor stated: “The Association was christened at the Pittsburgh meeting, and neither Mr. Phillips nor Mr. Von der Ahe was present.”52 Nonetheless Thorner recalled: “We called another meeting at the St. Clair Hotel, Pittsburgh and I brought on with me O.P. Caylor from Cincinnati and another reporter named Wright. These two, Mr. Phillips and myself were all the people who showed up…. Phillips and I took a stroll into Diamond Street and there learned that a baseball crank named Al Pratt was working in one of the mills and we found him. He told us of Denny McKnight and he was also secured. [W]e organized for all practical purposes, and I suggested that we have baseball representatives at Louisville, Washington, Philadelphia, New York, and St. Louis to send me their proxy as to where the next meeting should be held. We led everyone wired to believe that he was the only one absent from the meeting, and that caused an immediate reply.”53 In another account by Thorner from 1894, he stated: “It was during the latter part of 1881 that I read in some paper of a call for a meeting, at a Pittsburg hotel, of all those favoring a new baseball organization. In company with O.P. Caylor I took a run down to Pittsburg and…found the call to be on the order of a hoax, as no one showed up outside Caylor and myself. I inquired of the hotel keeper whether any one in town was fond of baseball, and was referred to Denny McKnight and Al Pratt. We called on these gentlemen…. We then declared the meeting adjourned to Cincinnati, November 2, and Caylor and I returned home.”54

The day after the meeting, numerous newspapers published virtually identical accounts. Possibly authored by Frank Wright of the Cincinnati Enquirer, the report was replete with misspellings and name-dropping, perhaps in an effort to impress prospective league members. It stated, with the correct names in parentheses, that temporary officers chosen were M.F. Day (John B. Day), of the Metropolitan club, Christ Van Derahe (Von der Ahe), James J. Williams (James A. Williams), and H.D. McKnight. Justus Thorner and Charles Fulmer were appointed to a committee to draft a constitution and by-laws.55 John B. Day was owner of the highly-successful independent professional New York-based Metropolitan club and James A. Williams was a former pitcher and the secretary, treasurer, and main driving force behind the recently defunct (Inter)National Association.56 Charles Fulmer was a prominent Philadelphia baseball player who accompanied the Athletics on their Western tour.57 Despite the supposed selection of officers, none of the accounts specifically stated who was actually present at the meeting.

The New York Clipper was more circumspect: “An informal meeting was held Oct. 10 in Pittsburg in the place of the proposed convention of clubs to organize a new Association, at which there were but two or three of the representatives of the clubs present who were to have sent delegates. After some talk together it was resolved to hold a meeting for permanent organization at the Gibson House, Cincinnati, Nov. 2.”58

Despite numerous unanswered questions, conventional wisdom holds to Harold Seymour’s account. That is, that Phillips instigated the meeting but dropped out; that Justus Thorner, Caylor, and Frank Wright went to Pittsburgh and met with Al Pratt and Denny McKnight; and that they sent to prominent non-National League clubs telegrams worded so as to give the impression that each absentee was the only one not present at the meeting.59

The American Association of Professional Base Ball Clubs formed on November 2, 1881, at the Gibson House in Cincinnati, Ohio, with six charter members; the Athletics of Philadelphia, the Atlantics of Brooklyn, St. Louis, Cincinnati, the Alleghenys of Pittsburgh, and the Eclipse of Louisville. Delegates to the convention included O.P. Caylor and Justus Thorner, Chris Von der Ahe, Billy Barnie, and Denny McKnight. Charles Fulmer represented the Athletics, and Horace Phillips represented the Philadelphia club of Al Reach. After some talk of consolidation, Fulmer was admitted as the representative of the Athletics, and Phillips was excluded. McKnight was made temporary chairman and Jimmy Williams was chosen temporary secretary.60 At the March 1882 meeting of the American Association, the Atlantic Club of Brooklyn resigned, to be replaced by a club from Baltimore.61

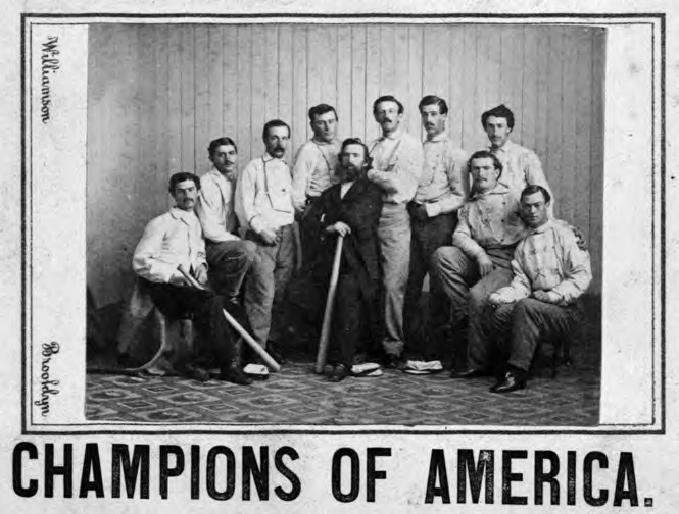

This 1865 photograph of the Atlantics of Brooklyn by Charles H. Williamson depicts the “Champion Nine” of 1864 and was given to opposing teams who played The Atlantic Club. In September and October of 1882 the club undertook a tour, making stops for multiple games in Philadelphia, Louisville, and St. Louis, with a second stop in Philadelphia on the way home. Such tours were part of the basis of formation of the league known as the American Association.

Afterword

Who should receive credit for the formation of the American Association? Alfred Spink and O.P. Caylor had been reporting baseball since 1875. Justus Thorner had been involved in Cincinnati baseball since 1879. Veterans Billy Barnie and Horace Phillips had faced each other on the field for years, including 1881, when their teams were members of the Eastern Championship Association. Spink helped form an independent team in St. Louis and encouraged Caylor to do the same in Cincinnati. Spink wrote to Philips and Barnie, inviting their teams west. Barnie and Phillips noted the success of teams in St. Louis, Cincinnati and Louisville. Caylor and Phillips met in September. Soon thereafter, Phillips issued the call for the first meeting. All these men deserve a measure of credit in this enterprise.

BROCK HELANDER is the author of “The Rock Who’s Who” (1982), “The Rock Who’s Who Second Edition” (1996), “The Rockin’ ’50s” (1998), and “The Rockin’ ’60s” (1999). Since joining SABR, he has been researching nineteenth century baseball, focusing on the history of baseball in cities that were represented in the major leagues exclusively in the nineteenth century.

Notes

1. Preston D. Orem, Baseball (1845–1881) from the Newspaper Accounts. (Altadena, California: Preston D. Orem, 1961), 14.

2. Marshall D. Wright, The National Association of Base Ball Players, 1857–1870 (Jefferson, North Carolina; McFarland & Co., Inc., 2000).

3. New York Clipper; April 27, 1878; New York Clipper, May 4, 1878

4. New York Clipper; April 12, 1879, Brooklyn Eagle; April 13, 1879, 4; New York Clipper. May 31, 1879.

5. Brooklyn Eagle, March 25, 1881, 1; New York Clipper, April 2, 1881; New York Times, April 12, 1881 8.

6. New York Clipper, October 13, 1883.

7. Wright.

8. New York Clipper, January 6, 1877; Chicago Tribune, March 4, 1877, 7; New York Clipper, March 10, 1877.

9. New York Clipper, April 6, 1878; New York Clipper, November 23, 1878.

10. New York Clipper, May 10, 1879; New York Clipper, May 8, 1880; New York Clipper, March 24, 1883.

11. New York Clipper, March 19, 1881; Brooklyn Eagle, April 17, 1881, 6; (Philadelphia) North American, May 16, 1881.

12. David L. Porter, Biographical Dictionary of American Sports: Baseball (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2000), 235–236; Frank V. Phelps, “Oliver Perry Caylor (O.P.),” Baseball’s First Stars (Cleveland: Society for American Baseball Research, 1996), 25; Sporting Life, October 23, 1897; New York Clipper, October 30, 1897.

13. Cincinnati Commercial Tribune, November 17, 1881, 4; Harold Seymour, Baseball: The Early Years (New York: Oxford University Press, 1960), 137.

14. Chicago Tribune, September 25, 1879, 5; The New York Times, October 25, 1879, 2; Chicago Tribune, October 28, 1879, 7; Chicago Tribune, November 16, 1879, 11.

15. New York Clipper, December 14, 1878; Brooklyn Eagle, November 17, 1879, 3; New York Clipper, December 13, 1879.

16. New York Clipper, January 3, 1880

17. New York Clipper, February 27, 1880.

18. St. Louis Globe-Democrat, October 5, 1880, 3; Chicago Tribune, October 5, 1880, 3.

19. Chicago Tribune, October 7, 1880, 5.

20. New York Sun, April 21, 1881; St. Louis Globe-Democrat, April 27, 1881, 6; Chicago Tribune, May 31, 1881, 6.

21. New York Clipper, July 2, 1881; Rocky Mountain News, October 2, 1882, 2; Cincinnati Commercial Gazette, December 31,

22. (Chicago) Daily InterOcean, August 28, 1881 3, citing the Buffalo Courier; Brooklyn Eagle, September 1, 1881, 3; Cincinnati Commercial Tribune, October 8, 1882, 7; Frank V. Phelps, “Oliver Perry Caylor (O.P.),” Baseball’s First Stars, 25.

23. Ray Schmidt, “Alfred Henry Spink,” Baseball’s First Stars, 156; William A. Kelsoe, St. Louis Reference Record: A Newspaper Man’s Motion Picture of the City (St. Louis: Von Hoffman Press, 1926), 14; Alfred H. Spink, The National Game (Carbondale and Edwardsville, Illinois: Southern Illinois University Press, 2000), 46; St. Louis Globe-Democrat, March 11, 1877, 6; New York Clipper, November 22, 1879.

24. St. Louis Globe-Democrat, April 12, 1880, 7; Washington Post, January 6, 1898, 8; The Sporting News, June 12, 1913, 4; Sporting Life, June 14, 1913, Vol. 61, Number 15, 9.

25. St. Louis Globe-Democrat, May 9, 1880, 12.

26. St. Louis Globe-Democrat, May 30, 1880, 13.

27. St. Louis Globe-Democrat, October 17, 1880, 2; St. Louis Globe-Democrat, October 31, 1880, 12; Spink, 46.

28. St. Louis Globe-Democrat, March 17, 1881 3; St. Louis Globe-Democrat, March 27, 1881, 11.

29. St. Louis Globe-Democrat, April 7, 1881, 7; St. Louis Globe-Democrat, 25 April 1881, 3; St. Louis Globe-Democrat, May 23, 1881, 7.

30. Hy Turkin and S.C. Thompson, The Official Encyclopedia of Baseball (New York: A.S. Barnes and Company, Inc, Third Edition, 1963), 309; Peter Palmer and Gary Gillette, ed., The 2005 ESPN Baseball Encyclopedia (New York: Sterling Publishing Co., 2005), 1294; New York Clipper, July 26, 1884.

31. New York Clipper, July 26, 1884; New York Clipper, May 28, 1881.

32. Brooklyn Eagle, March 25, 1881, 1; Brooklyn Eagle, April 26, 1896 16; Jack Kavanagh, “William Harrison Barnie (Bald Bill),” Baseball’s First Stars, 6.

33. New York Times, 23 November, 1937, 23; Daniel E. Ginsburg, “Albert George Pratt (Uncle Al),” Baseball’s First Stars, 128.

34. Peter Palmer and Gary Gillette, ed., 2489, 2492.

35. The Sporting News, 19 May, 1900, 1; Frank V. Phelps, “Henry Dennis McKnight (Denny),” Baseball’s First Stars, 109.

36. Spink, 47, 48.

37. St. Louis Globe-Democrat, May 30, 1881, 3.

38. Spink, 48.

39. St. Louis Globe-Democrat, July 4, 1881, 7; St. Louis Globe-Democrat, July 18, 1881, 8; New York Clipper, August 20, 1881.

40. Spink, 48, 50.

41. Brooklyn Eagle, January 30, 1898, 9.

42. New York Tribune, July 28, 1881, 8.

43. Cleveland Herald, August 16, 1881; New York Clipper, September 10, 1881; New York Clipper, October 18, 1881.

44. Cleveland Herald, September 3, 1881, 4; St. Louis Globe-Democrat, September 4, 1881, 3; St. Louis Globe-Democrat, September 5, 1881, 5; Cleveland Herald, September 6, 1881; St. Louis Globe-Democrat, September 9, 1881, 7; Cincinnati Commercial Tribune, September 9, 1881, 5; Cincinnati Daily Gazette, September 9, 1881, 2; New York Clipper, September 17, 1881.

45. Cincinnati Daily Gazette, September 10, 1881, 8.

46. Cincinnati Commercial Gazette, November 18, 1882.

47. New York Clipper, September 17, 1881.

48. Philadelphia Inquirer, September 15, 1881 3; Philadelphia Inquirer, September 16, 1881. 2; Cleveland Herald, September 19, 1881, 3; St. Louis Globe-Democrat, September 9, 1881, 5; New York Clipper, September 24, 1881; New York Clipper, October 1, 1881; St. Louis Globe-Democrat, September 25, 1881, 7; St. Louis Globe-Democrat, September 26, 1881, 3; St. Louis Globe-Democrat, September 27, 1881, 7; St. Louis Globe-Democrat, September 28, 1881, 5; St. Louis Globe-Democrat, September 29, 1881, 6; St. Louis Globe-Democrat, September 30, 1881, 6; St. Louis Globe-Democrat, October 2, 1881, 3; St. Louis Globe-Democrat, October 4, 1881, 2; St. Louis Globe-Democrat, October 9, 1881, 6; St. Louis Globe-Democrat, October 22, 1881; New York Clipper, October 10, 1881.

49. Buffalo Express, citing the Philadelphia Times, September 14, 1881.

50. Cleveland Herald, citing the Cincinnati Enquirer, September 17, 1881.

51. New York Clipper, September 24, 1881.

52. Cincinnati Commercial Gazette, November 18, 1882.

53. Pittsburgh Dispatch, November 9, 1889, 6.

54. Washington Post, March 11, 1894, 6.

55. Cincinnati Enquirer, October 11, 1881; Cincinnati Daily Gazette, October 11, 1881, 9; Chicago Tribune, October 11, 1881, 7; (Chicago) Daily InterOcean, October 11, 1881, 7; Cleveland Herald, October 11, 1881; St. Louis Globe-Democrat, October 11, 1881, 6.

56. David Pietrusza, “John B. Day,” Baseball’s First Stars, 49; New York Clipper, March 19, 1892.

57. New York Clipper, February 23, 1879; Joseph M. Overfield, “Charles John Fulmer (Chick),” Nineteenth Century Stars (Society for American Baseball Research. Manhattan, Kansas: Ag Press, 1989), 49.

58. New York Clipper, October 22, 1881.

59. Seymour, 137–138.

60. New York Clipper, November 12, 1881.

61. New York Clipper, March 18, 1882.