Prince Hal Chase and His Arizona Odyssey

This article was written by Lynn Bevill

This article was published in Mining Towns to Major Leagues (SABR 29, 1999)

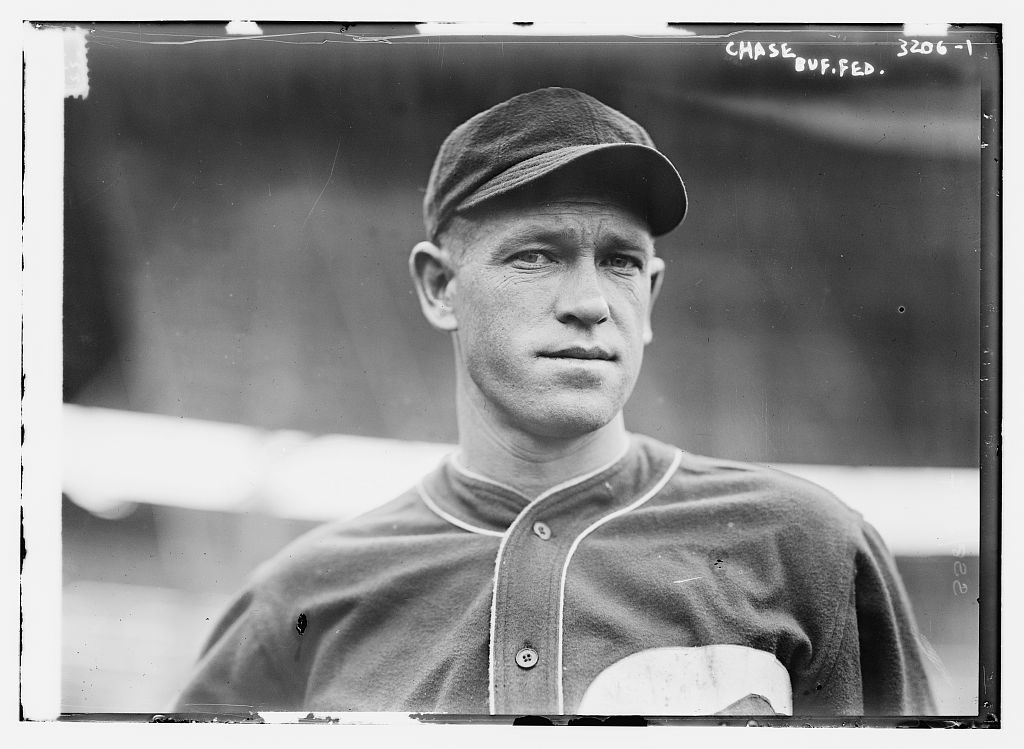

In 1923, former major leaguer Harold Homer Chase was chosen to manage the Nogales Internationals, a conglomerate of baseball players from both sides of the United States-Mexico border. Chase, called Hal or Prince Hal in recognition of his talents as a first baseman in the big leagues, continues to be one of the most controversial and enigmatic figures ever to play the game.

Chase was born in 1883 and grew up in the small town of Los Gatos, California, just outside of San Jose. Some reports say he attended and played baseball at Santa Clara College but the school has no record of his having attended classes there. He joined organized baseball in 1904 as a player for the Los Angeles Angels of the Pacific Coast League, playing his first game on March 23 and going 0-for-3 at the plate. Two years later he joined the New York Highlanders (now known as the Yankees) of the American League. Although he achieved tremendous success in New York, he never lost his close ties to the west.

From 1905 to 1907, Chase returned to California to play for San Jose of the California League after completion of the American League season. Many west coast leagues played well into November and major leaguers ventured to California to play in these circuits. Some played for the extra money and others for the expe1ience. The Cal League was not recognized by the National Commission of Baseball, the official body of Major League Baseball. After the 1907 season, the commission declared any individual playing in the California League would face expulsion from the majors. All of the major league players quickly dropped out except one. Hal Chase refused to conform, changed his name to Schultz and continued to play. It was one of the most poorly kept secrets in baseball and Chase was banned from returning to the major leagues.

The ban did not hold up, however, as Chase petitioned the National Commission to return and was reinstated for the 1908 season. When he returned, the popular Chase was presented with a silver loving cup from his teammates. It did not take Chase long to find himself in trouble again. He began his feud with Kind Elberfeld, the Highlanders’ manager, and then, with a month-and-a-half remaining in the season, Chase jumped the New York club for Stockton of the California League vowing that he would never play baseball in the east again. Like many of his declarations, this one was also quickly forgotten. Although the Oakland club offered him $9,000 to play for them in 1909, he declined and quietly returned to New York.

But he could not avoid controversy. In 1910, New York manager George Stallings accused Chase of throwing games. The charges were never proved and Chase replaced Stallings as the club’s skipper for the last 14 games of the season. In 1911, Chase’s first full season as a manager, the Highlanders finished in sixth place with a 76-76 record. The following year he relinquished the job as manager. His fame was such at this time that during the off-season he acted in a movie, Hal Chase’s Home Run.

Chase hit .274 and led the American League in errors in 1912 as the Highlanders finished in last place (50-102). During the 1913 campaign, Hal was traded to the Chicago White Sox. The following season he displayed more of the audacity that was to make him a thorn in the side of organized baseball. The newly organized Federal League offered Chase a contract to play in Buffalo. While Chase was still under contract with Chicago, every contract during that era included a clause that gave management the right to cancel any contract with only ten days’ notice. Chase, reasoning that what was fair for management was also fair for players, gave the White Sox a ten-day notice and then jumped to the Federal League. Upheld by the courts, Chase played the remainder of the 1914 season and all of the 1915 campaign in the Federal League. He was one of the league’s top stars but the league folded after the 1915 season and Chase’s rights were traded to Cincinnati. He joined the Reds in 1916.

Prince Hal’s first season in the National League was undoubtedly the best of his career. He continued to demonstrate his fielding talents while leading the NL in hitting. Although he played well, Chase again ran afoul of management. This time he took on Reds manager Christy Mathewson, one of the most respected figures in the history of baseball. Mathewson accused his first baseman of dogging it, doing poorly and making money by betting against his team. Mathewson reported the allegations to the NL president John Heydler before leaving for France where he was stationed during World War One. But Heydler cleared Chase of the charges.

In 1919, the New York Giants acquired Chase from the Cincinnati Reds. Before the season was over, Giants’ manager John McGraw suspended Chase for “poor play.” Whispers of throwing games continued to be heard whenever Chase’s name was mentioned. He would never play in the major leagues again. When the Black Sox Scandal involving the 1919 World Series came to light in 1920, Chase’s name appeared in the document that indicted eight members of the Chicago White Sox. The court sent a subpoena to California but the state refused to extradite Chase and no further action was taken against him.

Chase spent the 1920 season with San Jose in a weekend Class D league. In August of that year, the Pacific Coast League banned him from ever again entering a PCL stadium for attempting to bribe a pitcher to throw a game. After playing for various outlaw leagues in California, Chase was recruited and hired by the Nogales Internationals to play first base and manage the club for the 1923 season. The team consisted of players from Nogales, Arizona and Nogales, Sonora, Mexico. The club played its home games in both towns against teams from the United States and Mexico. Chase was popular in Nogales and was highly successful as a manager. His team beat traditional rivals Tucson and Phoenix, and finished the year with a barnstorming tour of Mexico that began in Sonora and ended in Mexico City. Prince Hal left the ball club at the end of the year but returned to Nogales from time to time.

When the 1924 season opened. Chase was in northern Arizona playing for a team in the town of Williams. It is likely that Hal was given a ‘job’ at the local Saginaw Manitee Box Company. well known for providing extensive help to the city teams, including giving jobs to key players. Chase only played for about six weeks but during his short time he made a strong impression on the boys of the town. Thomas Way, a local Williams historian, was a junior in high school when he and other boys would go to the baseball field and shag balls so Big Hal could practice batting. Sixty-five years later, Way remembered Chase as one of the nicest men he had ever met.

Chase also impressed his opponents. but he was unable to help the struggling Williams team. After a series with Jerome, he was recruited by the Miners to join their team as player-manager. Jerome was like many of Arizona’s small mining towns—baseball was taken seriously. Jerome’s arch-rival was the team from Clarkdale, the smelter town five miles down the hill. The rivalry between these two teams was intense and often degenerated into violence. During his first series between Clarkdale and Jerome, the Miners had been humiliated. Chase appeared to be just the cure for the sagging fortunes of the Jerome team. But Williams was not very excited about releasing Chase. Finally, a deal was struck that allowed Chase to go to Jerome. In return for his release, Chase was to come back to Williams to play in the big Fourth of July series against Flagstaff.

Chase kept his word and Williams captured two out of the three games in the annual Independence Day grudge match. With Chase at the helm, Jerome quickly became the powerhouse of the region. In the climatic final series with Clarkdale, the Miners beat the Smelters decisively. The rivalry had reached such a fever pitch that the United Verde Copper Company refused to sanction the two teams for the following season and forced the two towns to field a combined squad. Company employees that were hired to play baseball were let go, including Chase who was accused of pilfering from the stores at his job in the company hospital dispensary. Although the charges were never proved, Chase left Jerome and never returned.

In early March 1925, newspapers reported that Chase was negotiating with the President of Mexico to become commissioner of a new Mexican Baseball League. Chase said he was going to become the “Landis of Mexico,” referring to major league commissioner Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis. A follow-up article two days later confirmed that Chase was in direct contact with the Mexican government. This is where the story ends. It is unknown if the discussions were serious or if they were just the product of Chase’s vanity, trying to recapture a part of his fleeting fame.

Within two weeks of these strange news releases, Chase entered into negotiations with directors of the Douglas, Arizona team. Douglas, known as the Blues, had been an occasional member of a loose association of border teams. Teams from Arizona, New Mexico and Texas were represented, as well as clubs from Sonora and Chihuahua. At various times, the league was called the “Cactus League,” “Frontier League,” and the “Copper League.” The quality of play varied from year-to-year but many of the teams had evolved into semi-pro clubs with the players receiving a cut of the gate receipts as well as other benefits, such as a salary or a “job” with a local employer.

In 1927, Douglas did not field a team but Chase remained there selling Marmot automobiles at the local dealership. In July, rumors surfaced that the El Paso Giants were recruiting Chase to revive that club’s sagging fortunes. After month-long negotiations, Chase was induced to join El Paso. He arrived the second week of August and although he could still hit fairly well, the 44-year-old Chase was obviously suffering from the effects of his knee injury and, after the first weekend, he was quietly dropped from the team. His baseball career was winding down.

Chase returned to Douglas where he lived until returning to California in 1929. His Arizona odyssey, however, was not over. The Williams club brought Chase back in July, 1930 for one last tour. Combining several minor league players and some local recruits with Chase, Williams became the powerhouse of northern Arizona. Over Labor Day weekend, seven teams from the area were invited to play for the Northern Arizona Championship. Chase was named captain and the Williams club swept to the trophy. By the start of the 1931 season, Chase was no longer in the area and had moved on to perhaps Nogales or Tucson. In 1932, he suddenly reappeared in Williams and played in one game. There are reports that he also played in Winslow around this time.

Chase had most likely settled in Tucson by 1933. The 1935 Tucson city directory lists him as a resident with an occupation of “ballplayer.” He was still carrying his mitt in his hip pocket and reportedly was seen wandering around town looking for a game. During this period, he drank heavily and was often broke. Tucson resident Roy Drachman remembers Chase asking him for 15 cents to buy a loaf of bread.

Some time in 1935 or 1936, Chase returned to California and lived with his sister in Colusa. Over the final ten years of his life, he suffered from various illnesses including beri beri, a vitamin deficiency often associated with chronic alcoholism. Finally, in 1947 at the age of 64, Chase died. Hal Chase was not a role model. He married twice and had little success as a father. His son has few memories of his father and what he does have are mostly negative. That he gambled, drank and was a womanizer are well known. Moreover, it is likely that Chase bet for and against his own team, and dogged it at times to throw a game.

However, Hal Chase had another side that is more complex. Douglas, Arizona resident Chon Bernal tells of one evening when Chase came to Douglas’ Grand Theater smoking his usual big cigar. When someone pointed out a “no smoking” sign to Chase, he loudly announced, “The sign does not apply to me.” But a few minutes later when Bernal looked over at Chase, he noticed the bighead had not taken a puff, letting the cigar quietly go out. This was part of the Chase bravado. Perhaps this incident tells us something about Chase’s personality as a ballplayer. Perhaps rather than admitting he had booted a ball, he would rather wink and say he missed it on purpose. Perhaps he would rather have people think of him as a colorful player than one whose skills had begun to deteriorate late in his career. Maybe he saw more glamour in being associated with the fast set of gamblers and crooks than being just another fading ballplayer.

After leaving the big leagues, Chase began his Arizona odyssey that lasted twelve years. Although Chase never recaptured the glory of his days in New York, he confidently traveled the bush leagues of the Grand Canyon State as a very big fish in a very small pond. He was undoubtedly drawn to the rough-and-ready lifestyle that was still prominent in mining towns and the alcohol that flowed freely even during Prohibition. His time in Arizona fluctuated between temporary highs and miserable lows before he finally returned to California as a shell of who he once had been—Prince Hal, king of the first basemen.

Lynn Bevill is a school librarian in Tucson and one of the seven original members of SABR’s Arizona Chapter. His research interests include the history of minor league baseball in Arizona and the southwest.