Quantifying the Effect of Offseason Contract Extensions on Short-Term Player Performance

This article was written by Max Plithides - Greg Plithides - Muyuan Li

This article was published in Spring 2023 Baseball Research Journal

Over the past generation, sabermetricians have expended a great amount of time and energy studying the effects of free agency and long term contracts on player performance (Maxcy, Fort, and Krautmann 2002; Krautmann and Solow 2009; Krautmann and Donley 2009; Hakes and Turner 2011; Martin et al. 2011; O’Neill 2014; Paulsen 2020). How ever, they have spent far less time studying the effect of big offseason contract extensions on performance the following season. Here, an “offseason contract ex tension” is defined as any new contract signed during the offseason that adds additional years to a player’s contract with his current team.

Over the past decade, this line of inquiry has become increasingly important, as more contract ex tensions are being made and increasing amounts of money are being dedicated to these agreements. In the 2019-20 offseason alone, pre-free agency player ex tensions amounted to an enormous $1.7 billion (Sawchik 2019). Since 2020, many young stars including Wander Franco (21), Fernando Tatis Jr. (22), and Francisco Lindor (27) have foregone free agency to sign long-term deals with their clubs in excess of $200 million (MLBTR 2022). Yet a data deficiency regarding the short-term effects of these deals creates a sub optimal information environment that handicaps both teams and agents during negotiations.1 Agents, players, and teams have thus negotiated many recent mega extensions without large-N empirical data on their short-term performance effects. Given the billions of dollars at stake, there is an urgent need to address this dearth of empirical data.

We explore this topic through the lens of two competing hypotheses: that (H1) signing a pre-free agency offseason contract extension that buys out at least one year of free agency will hurt a player’s performance in the following season, and that (H2) signing a pre-free agency offseason contract extension that buys out at least one year of free agency will benefit a player’s performance in the following season. These hypotheses are mutually exclusive and derived from unique theoretical foundations. H1, which we refer to as the Negative Performance Hypothesis, derives from the concepts of shirking and stress-impairment.2 H2, which we call the Positive Performance Hypothesis, takes its inspiration from the psychological concept of positive reinforcement.3

We test these two hypotheses using a data set of all pre-free agency offseason contract extensions that bought out at least one year of free agency since September 2001 (N=182). Notably, the offseason criterion excludes those extensions signed in-season. We choose to exclude these in-season extensions because (1) they make up less than ten percent of all extensions, and (2) they have their own unique characteristics since the season played after and before the extension is signed is the same. We first treat the timing of a contract extension as a random occurrence and consider ex-ante and ex-post wins above replacement (WAR) and games played (G).4 We next run a second set of model specifications using WAR per game (WAR/G) in lieu of WAR to account for the possibility of injuries. Finally, we weaken the as-if random assumption and run two new model specifications—one comparing WAR, G, and WAR/G post-extension to a player’s averages over the previous three seasons, and another comparing a player’s performance post-extension to their performance two years before the extension. The idea here is to remove from the equation the player’s choice as to the timing of when to negotiate an extension.5

THEORY

Much of the literature regarding long-term contracts hints at the role of shirking in poor production from players. “Shirking” here is not meant in a pejorative or layman’s sense; teams often encourage shirking as an economically rational form of asset protection for players who they have just signed to long-term deals. Significant evidence supports the notion that shirking in this non-pejorative sense may impact player performance. O’Neill (2014) finds that hitters generally boost their performances during contract years before performing worse when under a long-term contract. Work by Maxcy, Fort, and Krautmann (2002) demonstrates a nearly identical phenomenon at play among pitchers. It shows that pitchers with nagging injuries may be more likely to be placed on the injured list while under long-term contract. The study by Martin, Eggleston, Seymour and Lecrom (2011) similarly evokes the idea of the contract-year phenomenon as evidence of economically strategic behavior that may be attributed to shirking.

More recently, Paulsen (2020) goes beyond merely hinting at the role of shirking in causing poor player performance. By using a player fixed-effects estimation strategy, Paulsen (2020) eliminates much of the uncertainty caused by multi-collinearity concerns in existing player data.6 Paulsen (2020) also addresses alternative explanations for the observed shirking, such as teams signing improving players to multiyear contracts or players facing an adjustment process when joining a new team. Even when alternative explanations are considered, Paulsen (2020) still finds that shirking behavior principally drives the generally inverse association between years left on a contract and a player’s performance.

Still, a disconnect exists between scholars’ findings and the testimony of players. Players rarely cite shirking as the cause of their down seasons. Rather, they commonly attribute negative performances following extensions to the increased psychological stress that comes with money and job security. As Jason Kipnis explained to reporters in 2014:

I might have taken [my extension] the wrong way. There’s one of two ways to go about it. There’s ‘Hey, I have the security and the money now I can go out and just play the game of baseball.’ I took the way, where, ‘I’ve got this money, I’ve got to live up to it.’ So I might have pressed at the beginning and tried to do too much. In hindsight that could have hurt me and played a little part of [my down] season.

(Gleeman 2014)

Kipnis’s logic, while not supported by research, makes intuitive sense. One would expect large contracts to increase stress levels for already well-paid professionals. According to both physicians and psychologists, stress-distracted athletes generally suffer more injuries than their undistracted counterparts and require more time off as a result (Schultz and Schultz 2015, 265-66; Reardon et al. 2019). They may also feel pressured to perform well, causing them to counterproductively try too hard—what Kipnis calls “pressing”—creating sub optimal outcomes on the field. Yet irrespective of whether the cause is stress or shirking, both point to worse performance following an offseason contract extension. This brings us to Hypothesis 1.

Hypothesis 1—Negative Performance: Signing a pre-free agency offseason contract extension that buys out at least one year of free agency will hurt a player’s performance in the following season.

Conversely, there is at least one reason to believe that an offseason contract extension may benefit a player’s performance in the following season. A con tract extension coming off a good season could serve as a form of positive reinforcement. Positive reinforcement refers to the introduction of a desirable or pleasant stimulus after a behavior where the desirable stimulus reinforces the behavior, making it more likely that the behavior will reoccur (Doggett and Koegel 2012). Money qualifies as a positive stimulus, and ob servers often assume that when organizations extend players, buying out several years of free agency, they are expressing faith in or rewarding their previous performance.7 This brings us to our second hypothesis.

Hypothesis 2—Positive Performance: Signing a pre-free agency offseason contract extension that buys out at least one year of free agency will benefit a player’s performance in the following season.

Finally, we also offer the caveat that neither H1 nor H2 may be valid. Signing a pre-free agency offseason contract extension that buys out at least one year of free agency may simply not affect player performance in the following season. While we do not expect this, we must account for the possibility and label this out come our null hypothesis.

METHODOLOGY

To arbitrate between the two hypotheses and their null, we create an original data set (N=182) of all pre-free agency offseason extensions signed between January 2000 and June 2022 that bought out one or more years of free agency. We begin with an open-source data set from MLB Trade Rumors (2022), which includes all contract extensions signed during the period in question. We then hard-code whether each extension occurred during the regular season and add data on the number of years of free agency bought out, including potential options years.8 Finally, we permute our data set by adding open-source data on player performance from Baseball Reference (2022a, 2022b).

In particular, we collect data on WAR, games played, and WAR/G as critical measures of performance. WAR sums up a player’s performance holistically in a single summary statistic, making it ideal for parsimonious statistical analyses.9 Games played measure a player’s ability to stay healthy and speaks to their psychological state,10 since research shows that shirking and/or stress-distracted athletes generally take more time off with injuries (and suffer more injuries) than their motivated and undistracted counterparts (Schultz and Schultz 2015, 265-66; Reardon et al. 2019).11 Finally, WAR/G allows us to evaluate performance using an “injuries as random” assumption. While scholars have found little evidence to support the notion that injuries occur randomly (e.g. Timmer man 2007), athletes often speak about injuries as products of chance (Sawchik 2019). WAR/G thus allows us to consider that “baseball players have accidents,” and that “stuff happens in life, and sometimes people get hurt and there is not always a reason for it” (Schultz and Schultz 2015, 265).

We also measure the independent and dependent variables—ex-ante and ex-post performance, respectively—in different model specifications using the three measures of play quality outlined. In each model specification, the season following the signing of the contract extension is used to measure short-term ex post performance. Yet it is less obvious how ex-ante performance should be measured when contract extensions are signed. We therefore model the independent variable (IV) using three different specifications for the sake of transparency.

To begin with, we measure ex-ante performance (the IV) in terms of the season preceding the extension. We prefer this measure of the IV because the comparison makes the most casual and intuitive sense. Under this scenario, the timing of an extension is taken to be as-if random in relation to player performance. This permits us to conceptualize the signing of a contract as a treatment effect occurring within a natural experiment. Yet the as-if random assumption requires further justification, since “the plausibility of as-if random assignment stands logically prior to the analysis of data from a natural experiment.” (Dunning 2012, 235)

We therefore seek here to justify the as-if random assumption on two grounds: observations from agents and players and previous research. While extensions of players following good seasons may receive positive press coverage—creating the perception that extensions generally serve as rewards for positive performances— there is surprisingly little large-N data to support this notion. Former MVP Shohei Ohtani, for instance, signed a two-year contract following a -0.4 WAR season in 2020. Similarly, Francisco Lindor signed a $341 million deal following a .750 OPS season in 2020, and in 2011, the Reds inked Nick Masset to a 2-year extension following a down season in which he posted his lowest single-season ERA since 2008. There is thus little reason observationally, in the absence of large-N data, to expect that contract extensions would solely follow good or bad seasons.

One agent described teams’ willingness to negotiate extensions at almost any point in a player’s career as bordering on predatory:

Every time the teams see a seam in the defense [resistance to signing an extension], they exploit the shit out of it… . The teams have scouting reports on agents… . They have heat maps. They know our tendencies, they know who will go to arbitration, who won’t, whose business is failing and [who] need[s] to vest their fees.

(Sawchik 2019)

Previous research (Krautmann 2018) also provides passing credence to the logical and observational in tuition that performance and extension timing are unrelated. Based on previous statistical analysis, players are most likely to be extended when they have one year remaining on their existing contract (Krautmann 2018). Notably, that is not a performance-based selection effect. While that means that contracts are not offered entirely randomly, they are likely offered on an as-if random basis relative to performance. Essentially, while contract timing may involve much ruminating on a case-by-case basis, on average it is statistically as-if random vis-à-vis performance.

In the interest of transparency, we test our theory with a weakened as-if random assumption by considering a three-year average of previous performances, along with performance in the season two years before the extension.12 Players who did not have a two- or three-year history in the majors were excluded from these analyses. We break our data into three groups: hitters, all pitchers, and starting pitchers.13,14 Displaying our data this way allows consideration of heterogeneous effects. Finally, controls are collected for and included in the dataset.15

RESULTS

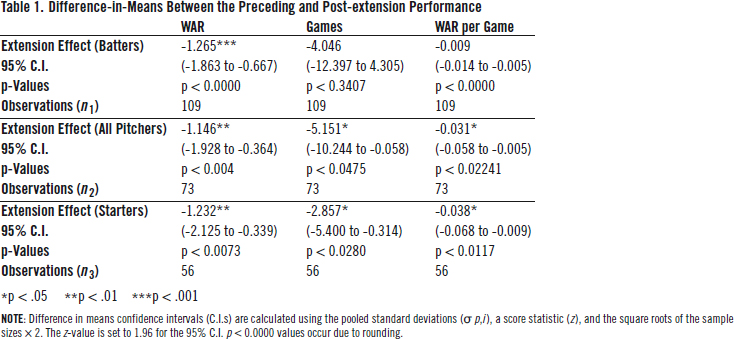

Table 1 presents the difference-in-means results for player performance in the seasons before and after an extension was signed. We observe nontrivial statistical evidence at the 95 % level for the Negative Performance Hypothesis across most measures of performance irrespective of position. Players commonly perform at a lower level following the signing of an offseason ex tension. We thus reject the Positive Performance Hypothesis and the null hypothesis, given our strong belief that the timing of extensions is as-if random with regards to performance and our preference for the IV measure used in Table 1.

There is a notable post-extension drop-off in WAR, games played, and WAR/G. However, the level of drop-off varies by position. WAR shows the least heterogeneity, with extensions causing players of all stripes to be worth (on average) about one win less (batters’ coefficient: – 1.265; pitchers’ coefficient: -1.146; starters’ coefficient: – 1.232). In terms of games played, there is a large amount of variance be tween positions. Pitchers are much more likely to miss starts due to injury in the season following the signing of an extension (coefficient: – 2.857, p < 0.0280). Re lief pitchers show an even greater drop-off, although the sample size is small and their usage is heavily situation-dependent.16

We suggest three possible reasons for the drop-off in games among pitchers. First, pitching is a high-stress activity that can cause permanent damage to the body. It follows that financially secure pitchers might rationally shirk more to protect their long-term health, and that management may have a significant part in actively encouraging such shirking as a form of long term asset protection. Second, pitchers appear much less frequently than hitters and may therefore be under greater stress when they do come into the game. Greater stress correlates directly to heightened injury risk and longer injury recovery time (Schultz and Schultz 2015, 265-66; Reardon et al. 2019). Finally, the possibility of regression to the mean must be acknowledged here with regards to health. While contract extension timing may be reasonably assumed to be as-if random with regards to performance, far less research has been done on its relation to health. Pitchers may simply be more likely to be extended coming off of a healthy season creating unforeseen selection effects.

To address this concern, for our third specific measure of performance, we utilize WAR on a per game basis. The WAR/G difference-in-means metrics measure whether there is still a drop-off if we treat injuries as random events rather than products of a player’s psychological state. As can be seen clearly, the WAR/G metric reveals evidence of a drop-off similar to the previous two. The – 0.009 per game drop in batters’ average performance comes out to – 1.458 wins lost over the full course of a full season. Similarly, the – 0.038 lost by pitchers per start comes out to – 1.254 WAR over the course of thirty-three starts. Essentially, even if all injuries were caused by uncontrolled misfortune, healthy players would still play noticeably worse the season after receiving a contract extension.

All three metrics support the Negative Performance Hypothesis when the baseline for ex-ante performance is considered as performance in the season preceding the extension. However, while we strongly believe in the as-if random assumption that this finding relies on, others may be more skeptical. What happens when we remove the as-if random assumption by using longer-term baselines for measuring ex-ante performance?

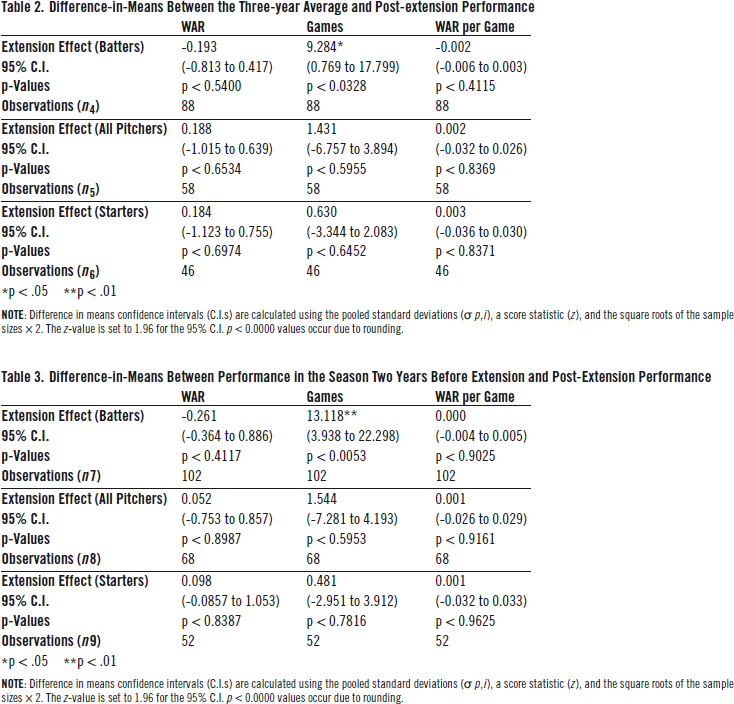

Table 2 indicates that there is no statistically significant correlation between pre-extension and post-extension performance according to most meas ures of performance. The one exception is games played by batters, which seem to increase. We attribute this to a number of players in the sample who were rookies in year one of their three-year averages. We next turn to performance in the season two years be fore the extension.

The results in Tables 2 and 3 are almost identical. Games played increases significantly for batters once again, this time with an even more significant p-value (p <0.0053). Removing all rookies from the data con firms that they are driving this finding. The p-value (p <0.2154) is now no longer significant. Players of all stripes play similarly after receiving an offseason extension and in the season two years beforehand.

The findings in Tables 2 and 3 are noteworthy. While we stand by our as-if random assumption, if future studies show it to be false, then our findings would instead support the null hypothesis. This adds a significant wrinkle to what would otherwise be a decisive finding in support of the Negative Performance Hypothesis.

CONCLUSION

This article demonstrates that on average-contingent on performance and extension timing being uncorrelated-signing an offseason extension that buys out one or more years of free agency causes a substantial drop in player performance the following season. The underlying theory is that by simultaneously facilitating shirking and ramping up stress, extensions hurt short term ex-post performance.

However, there is an important caveat to this finding. Using performance from the three-year average, and the season two years before the contract extension, the results demonstrate that the Negative Performance Hypothesis is not robust enough to with stand weakening of the as-if random assumption. If player performance were to determine extension timing, this paper would support the null hypothesis rather than the Negative Performance Hypothesis. We therefore encourage further research into the relation ship between performance and extension timing.

These findings also suggest other areas for future research. First, our dataset excludes players who sign in-season extensions in order to minimize selection effects.17 Future research could examine in-season extensions more closely as an uncommon but financially lucrative subset of extension.18 Second, the results for pitchers and hitters vary substantially. Although we offer several possible explanations, future saber-metricians should examine the potential causes of this discrepancy in more detail to elucidate further contract-response differences between pitchers and hitters. Third, we recommend that researchers examine the possibility that players’ performances may improve in the second year following a new contract extension. While players may generally see a decrease in performance one year after signing a new contract extension, regression to some performance-based mean may be more likely by year two of a new con tract extension. Current projections systems certainly assume such regression. We thus suggest that the value of extensions beyond the first year be tabbed for further investigation. Finally, researchers should consider expanding our sample size to include players who were extended but whose free agent years were not bought out. Given the increasing frequency of extensions that buy out arbitration years, this could provide valuable data to front offices on whom to go to arbitration with and whom to extend. This study thus points to a broader research agenda with the potential to have a significant real-world impact.

MUYUAN LI works at Blizzard Entertainment where she manages several data teams. She is an avid fan of both real and fantasy baseball and frequently drives down the road to watch Shohei Ohtani make history and drop bombs. She holds a B.B.A. in Applied Information Management Systems from Loyola Marymount University. If you have feedback or would like to request replication data please email her at muli@blizzard.com.

GREG PLITHIDES recently joined SABR as a new member in summer 2022. An engineer by training, he has a particular love for fantasy baseball and a natural proclivity for Sabermetrics. He holds a B.S. in Mechanical Engineering from Columbia University.

MAX PLITHIDES is a PhD candidate at the University of California, Los Angeles, and an Adjunct Professor in the Department of Political Science and International Relations at Loyola Marymount University.

Sources

Baseball-Reference.com. 2022a. “Daily Updated Batting WAR Data (in CSV).” Baseball-Reference.com, V2.2. Accessed July 23, 2022. https://www.baseball-reference.com/data/war_daily_bat.txt.

____. 2022b. “Daily Updated Pitching WAR Data (in CSV).” Baseball-Reference.com, V2.2. Accessed July 23, 2022. https://www.baseball-reference.com/data/war_daily_pitch.txt.

Doggett, Rebecca, and Lynn Koegel. 2012. “Positive Reinforcement.” In Encyclopedia of Autism Spectrum Disorders, edited by Fred R. Volkmar, 2299. New York, NY: Springer.

Dunning, Thad. 2012. Natural Experiments in the Social Sciences: A Design-Based Approach. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Gleeman, Aaron. 2014. “Jason Kipnis Thinks Pressure of Contract Extension Led to Poor Season.” NBC Sports. https://mlb.nbcsports.com/2014/09/11/jason-kipnis-thinks-pressure-of-contract-extension-led-to-poor-season.

Hakes, Jahn Karl, and Chad Turner. 2011. “Pay, Productivity and Aging in Major League Baseball.” Journal of Productivity Analysis 35 (1): 61-74.

Krautmann, Anthony C. 2018. “Contract Extensions: The Case of Major League Baseball.” Journal of Sports Economics 19 (3): 299-314.

Krautmann, Anthony C., and Thomas D. Donley. 2009. “Shirking in Major League Baseball Revisited.” Journal of Sports Economics 10 (3): 292-304.

Krautmann, Anthony C., and John L. Solow. 2009. “The Dynamics of Performance over the Duration of Major League Baseball Long-Term Contracts.” Journal of Sports Economics 10 (1): 6-22.

Martin, Jason A., Trey M. Eggleston, Victoria A. Seymour, and Carrie W. Lecrom. 2011. “One-Hit Wonders: A Study of Contract-Year Performance Among Impending Free Agents in Major League Baseball.” NINE: A Journal of Baseball History and Culture20 (1): 11-26.

Maxcy, Joel G., Rodney D. Fort, and Anthony C. Krautmann. 2002. “The Effectiveness of Incentive Mechanisms in Major League Baseball.” Journal of Sports Economics 3 (3): 246-55.

MLB Trade Rumors. 2022. “Extension Tracker.” MLB Trade Rumors. Accessed July 23, 2022. https://www.mlbtraderumors.com/extensiontracker.

O’Neill, Heather M. 2014. “Do Hitters Boost Their Performance During Their Contract Years?” The Baseball Research Journal 43 (2): 78-85.

Paulsen, Richard J. 2020. “New Evidence in the Study of Shirking in Major League Baseball.” Journal of Sport Management 35 (4): 285-94.

Reardon, Claudia L., Brian Hainline, Cindy Miller Aron, David Baron, Antonia L. Baum, Abhinav Bindra, Richard Budgett, et al. 2019. “Mental Health in Elite Athletes: International Olympic Committee Consensus Statement.” British Journal of Sports Medicine 53 (11): 667-99.

Rogust, Scott. 2022. “Fernando Tatis Jr Has the Moves On and Off the Field.” Fansided, February. https://fansided.com/2022/02/18/fernando-tatis-jr-moves-off-off-field-video/.

Sawchik, Travis. 2019. “What’s Behind MLB’s Bizarre Spike in Contract Extensions?” FiveThirtyEight, April. https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/whats-behind-mlbs-bizarre-spike-in-contract-extensions.

Schultz, Duane, and Sydney Ellen Schultz. 2015. Psychology and Work Today: An Introduction to Industrial and Organizational Psychology. 10th ed. New York, NY: Routledge.

Timmerman, Thomas. 2007. “It Was a Tough Pitch: Personal, Situational, and Target Influences on Hit-by-Pitch Events Across Time.” Journal of Applied Psychology 92 (3): 876-84.

Tomlinson, Edward C., and Roy J. Lewicki. 2015. “The Negotiation of Contractual Agreements.” Journal of Strategic Contracting and Negotiation 1 (1): 85-98.

Notes

1. Sub-optimal information environments benefit nobody. See Tomlinson and Lewicki (2015).

2. Rational shirking is derived from rational choice theory and behavioral economics. Stress-impairment is grounded in neuropsychology and medicine.

3. Positive reinforcement is rooted in behavioral psychology.

4. An event is considered “as-if random” when its occurrence is unassociated with some variable of interest. In this case, we posit that extension timing is uncorrelated with a player’s performance in the preceding season. Contract extensions are obviously not a completely as-if random occurrence in a player’s career, but we begin with strong simplifying assumptions before relaxing them later.

5. We discuss at length why we believe the timing of extensions to be uncorrelated with performance in the methods section, but more research is needed in this area.

6. A fixed-effects model refers to a regression model in which group means are fixed (non-random). In Sabermetrics, this type of model is valuable for analyzing data that includes multiple seasons from a single player.

7. See, for instance, Fansided staff writer Scott Rogust’s description of Fernando Tatis’s recent extension as a “reward” for an “incredible 2020 season” (Rogust 2022).

8. The coding process was generally straightforward with two exceptions. First, extensions signed on the first and last days of the season are coded as “offseason,” due to the inability to collect down-to-the-minute data. Second, extensions signed after opening days in other countries but before opening days in North America are also coded as “offseason,” since overseas opening days involve only two teams and often occur far in advance of their North American counterparts.

9. WAR is pro-rated in our data set for the shortened 2020 season.

10. Games played are pro-rated in our data set for the shortened 2020 season.

11. For relief pitchers, games played are also largely a product of managerial decisions.

12. Faith in the as-if random assumption is decisive in determining how one should interpret our results. We still include our null alternative specification results, however, because we believe in the value of research transparency.

13. We classify Shohei Ohtani as a hitter.

14. We classify a player as a starter if he made fewer than thirty-six appearances in a regular season and started at least one game.

15. Controls are not used in our in-paper analysis to avoid introducing statistical bias into our natural experiment’s difference-in-means results. That said, controls were collected, and the full dataset with controls is available upon request.

16. Relief pitchers are not shown on their own in the data, but the drop-off can be inferred from the difference between the games played difference-in-means results between starting pitchers and “pitchers” generally.

17. Pre-season preparation, after all, cannot be undone by signing a contract.

18. In-season extensions can be very large. Jose Ramirez, for instance, just signed a 5-year $124 million extension in-season.