Red Moore: He Could Pick It!

This article was written by James A. Riley

This article was published in The National Pastime: Baseball in the Peach State (Atlanta, 2010)

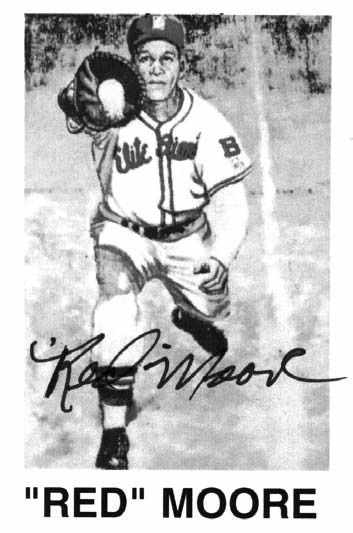

Whenever a Negro Leagues veteran is asked about James “Red” Moore, the response is almost automatically: “He could pick it!” Then the player adds anything else that he has to say. Such is the reputation that the Atlanta-born former baseball star earned during his career in the Negro Leagues.

Described by Atlanta Daily World sports editor Ric Roberts as the “most perfect” first baseman ever, Red was expert at handling ground balls, excelled at making a 3-to-6-to-3 double play, and was masterful at digging low throws out of the dirt and gloving other errant throws while making it look easy.

Buck O’Neil, a star first baseman for the Kansas City Monarchs and a contemporary of Moore, said of his rival: “He could pick it! He was quick around first base and had outstanding hands. He could handle that low throw in the dirt better than anybody. Nobody had better hands than Red Moore. Most first basemen back then used two hands, but Red was a one-hand first baseman. As far as playing first base, nobody was better. People came to see him play.”

And Red, who liked to showboat on occasions, never disappointed them. Frequently, the fancy fielder would take throws behind his back in pregame infield practice and make other trick catches to entertain the fans. The home folks adored him, and he became a crowd favorite everywhere he played.

The second of four children born to James Benjamin Moore Jr. and Sadie Robinson Moore, Red reflects back over his early years living in the Bush Mountain neighborhood of southwest Atlanta. He learned his craft the hard way. As a left-handed youngster, he made his first mitt by taking apart a standard right-hander’s glove, turning it inside out, and restitching it. From that rudimentary beginning with a makeshift glove, the aspiring young ballplayer developed into a flawless “one-hand” fielder whose defensive skills would eventually attract the attention of top black baseball teams.

His creativity carried over to his hitting and, early in his professional career, he pioneered the use of a batting glove. Red describes his role in the development of this new piece of equipment: “The pitchers were throwing me inside and the ball came right in on my fists, right up on my left hand—my top hand—and when I hit the ball, it would sting. So I got a glove like we used to use in cold weather—a good leather dress glove we would wear in the wintertime—and cut the fingers off. I wore that on my left hand. I could grip a bat pretty good and when I hit the ball it would take the sting out of it. That was in ’36 or ’37, and I used it the rest of my career.”

It was around this same time that Moore, as a raw rookie with the Newark Eagles, received an unforgettable welcome to black baseball’s big time from Satchel Paige. Red now laughs when he recalls the first time he faced Satchel. Speaking to a group of schoolchildren in the Hank Aaron Room at Turner Field in 2006, the aged veteran looked back 70 years to that first encounter with the legendary pitcher.

Actually, it was an encounter with two legends. Satchel’s batterymate that day was Josh Gibson, the great slugger known as the “Black Babe Ruth.” Gibson was noted for talking “trash” to hitters—especially young ones—in an attempt to intimidate them or at least to shake their confidence and break their concentration. This time was no exception, and Gibson bantered with the “green” batter as he stepped up to the plate. Red remembers his initiation vividly: “Josh said, ‘Young man, I heard you’re a pretty good hitter— can you hit laying down? When Satchel faces a rookie the first time, he kinda lays ’em down. You better watch, young buck, we’re going to have to check you out.’ Satchel was on the mound and I’m listening to Josh and then all of the sudden the ball popped like a shot in Josh’s mitt. He said, ‘That was pretty close and next time it’s going to be a little closer. You know you can’t hit laying down.’ And while Josh is talking, another fastball zipped by me. Then another one. I just kind of waved at ’em.”

After Satchel hummed three straight fastballs by him before he had really settled into the batter’s box, the rookie had to face his manager’s ire in the dugout. A smile creases Red’s face as he describes his discomposure at the time: “W. Bell was manager then. When I got back to the dugout he said, ‘You’ve been hitting good ’til now—what happened?’ I said, ‘Mr. Bell, Josh is back there and he made me nervous. I was listening to him and didn’t watch the ball.’” The old warhorse chuckles, recalling the experience, and adds, “The first time I faced Satchel, I didn’t do nothing. And I never did do much against him.” Red’s rookie experience was not unique. Few players—rookies or otherwise—hit Satchel.

After this disquieting experience, Red settled into his role with the Newark ballclub. The fielding wizard added finesse to his team’s defense everywhere he played, but nowhere was it more apparent than with the Eagles in 1937, where he was part of their famed “million dollar infield.” Slugger Mule Suttles divided his time between first base and the outfield during his career but, when Red arrived on the scene, the big slugger spent more time in the outfield in deference to the youngster’s sterling defensive skills.

Once ensconced at the initial sack, Red teamed with second baseman Dick Seay, shortstop Willie Wells, third baseman Ray Dandridge, and catcher Leon Ruffin to give the Eagles Gold Glove quality at each infield position. Dandridge said, “Now, when he was at first base, that was our million-dollar infield.” Wells echoed that sentiment, praising Red’s defensive play lavishly. Dandridge and Wells are now members of the Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York. Two of Moore’s other teammates at Newark, Leon Day and Monte Irvin, are also among the Cooperstown elite, and both concurred with their former teammates’ assessment and added their own high praise of Red’s superior defensive prowess.

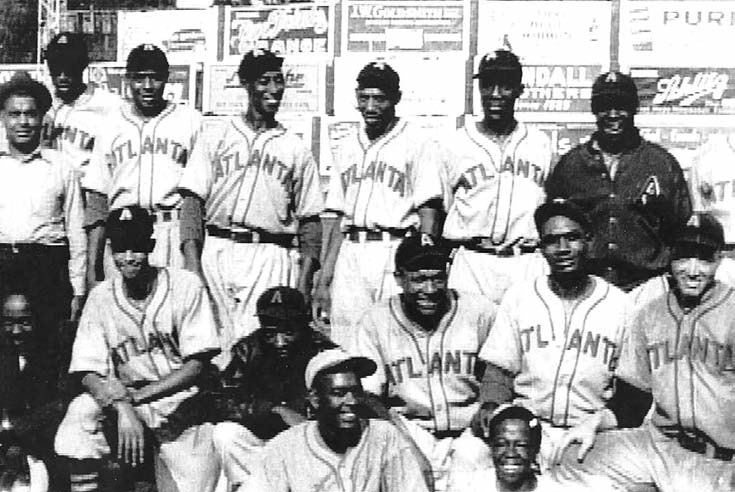

Following his stint in Newark, Red returned to his hometown in 1938 and helped the Atlanta Black Crackers become the first Atlanta team in any major league sport to win a championship. Although winning his greatest acclaim with his superb defensive skills, the left-handed batsman also had some good seasons at the plate, batting .320 with the 1938 Atlanta Black Crackers, when the team captured the second-half championship of the Negro American League’s split season. The resulting playoff with the first-half champion Memphis Red Sox was not completed, and the NAL president subsequently declared a co-championship.

Although he could pilfer a base when the game situation called for it, Red did not present a base-stealing threat. In fact, a base-running mishap led to an injury sliding into a base and put him on the shelf for an extended time during the Black Crackers’ title run. The irony is that this occurred in an exhibition game. Red describes the incident: “I cracked my left ankle going into second base. I made a late slide, and my spikes hung up under the base. I was out about six weeks, and it kept me from playing in the East–West game. I wore an ankle brace, and that kind of stabilized it. They didn’t put it in a cast, but I was on a crutch for awhile. I was in the dugout for our home games, but I didn’t do no traveling. I was kind of incapacitated. I wasn’t a fast man anyway, even before the injury. After I got back in the lineup is when we began our big winning streak and won the second-half championship.”

Although Ted “Double Duty” Radcliffe was 102 years old and in poor health, his memory remained sharp about the 1938 Atlanta Black Crackers and one of the best first basemen he ever saw: “They had a heck of a ballclub. I managed the Memphis Red Sox in the championship playoff against them. Red Moore was a great fielder. He could pick it! And he was a good all-around ballplayer.”

Off the field, Red was quiet, unassuming, and practical. Radcliffe also voiced his respect for his opponent as a person and spoke of how well liked he was. “He was one of the best fellows I ever met.” Buck O’Neil concurred: “I knew Red on the field and, after he stopped playing, I’d see him every time we would play in Atlanta. Red was always a good person. He was always a churchgoer.”

This admiration of the Black Crackers’ star was not isolated, and Red Moore’s contribution to the team’s success did not go unnoticed in Atlanta, where the fans held a special day for him at Ponce de Leon Park to show their appreciation. Despite the restrictive economics of the Great Depression, the grateful fans presented the star first sacker with $350 worth of gifts and merchandise.

In addition to the fans, another Atlantan who admired the way that Red Moore played the game was Earl Mann, president of the white Atlanta Crackers, who earlier in the season had tried to sign the flashy fielder to a contract with his ballclub and pass him off as a Cuban. Red explains why he declined the offer: “Earl Mann wanted me to learn a little Spanish to help the ruse to succeed, but I knew that wouldn’t work. Everybody around Atlanta knew me. They all had seen Red Moore play, and I knew what would happen. They would’ve been calling me all kind of names, and I didn’t want any part of that. I stayed where I was with the Black Crackers.”

The press also noted his sterling performance, and at the end of the season, the Southern News Service selected Moore to the Negro American League’s AllStar team. What more could a young ballplayer ask than to be an All-Star in his hometown?

In 1939, the Black Crackers relocated to Indianapolis and played briefly as the ABCs before disbanding early in the season. Afterward, Moore was quickly signed by the Baltimore Elite Giants, where he roomed with Roy Campanella, who later became an All-Star catcher with the Brooklyn Dodgers and subsequently was voted into the Hall of Fame.

Both players were respected by their opponents and well liked by their teammates, and their similar personalities made them compatible roomies. Red remembers the years with his young roommate fondly: “I was about six years older than Roy. At that time he was just a teenager. He was a nice young fellow, good to be around. He was always telling jokes. He loved baseball—he loved the game. His dad would ride with us on the bus. He loved the game like we did and would be with us. He was Italian, but there was no problem with meals, accommodations, or anything— he would go where we would go.”

Both young players were easygoing off the field but competitive on it, where the Elites battled Red’s old team, the Newark Eagles, and the dynastic Homestead Grays for the Negro National League pennant. In the end, the Elites lost out to the defending-champion Grays. Absent a championship playoff, the top four teams played a postseason tournament, and this time the Elites emerged victorious over the Grays to claim the championship trophy. Photographs snapped after the final game, which was played at Yankee Stadium, show the jubilant young roomies in the front row of the team picture.

When I mentioned his old roommate to Campy one year at Cooperstown, his face lit up and a smile spread across his face. “Yes,” Campy agreed emphatically, “He could pick it!”

Both Campy and Red returned to the Elites the following spring and, at that point in Red Moore’s life, the world looked rosy to the young star. Little did he know what changes lay just around the corner.

Late in 1941 Red was married, but soon afterward the United States entered World War II, and he was inducted into the army in 1942. During the next three years, he served in England, Belgium, and France in a combat-engineer battalion attached to General George Patton’s Third Army. After the war ended, he was discharged in 1945 and returned to Atlanta. However, the years of athletic rust had taken their toll and, although he resumed his baseball career on a part-time basis, he never again played at the major-league level.

Leaving baseball in 1948, Red took a job in Atlanta with Colonial Warehouse until retiring in 1981. In retirement, he has retained a quiet demeanor and still loves chicken dinners, his favorite meal.

At age 93, Red resides in Atlanta with his wife Mary and remains active in his church and community. He serves as Deacon Emeritus at the Springfield Missionary Baptist Church and has given talks about his baseball career at a wide range of venues, including public schools, colleges, civic clubs, and SABR meetings. During the past four years, he has spoken to over one thousand school children in the Hank Aaron Room at Turner Field, as part of the Atlanta Sports Hall of Fame educational program.

Recognition came late in life for Red Moore. Once ignored to the point of invisibility, the Negro Leagues legend is belatedly receiving honors and recognition all across the country. He has appeared at numerous special functions and has been featured on television and in newsprint. In his hometown, the Mike Glenn Foundation presented him with a Pioneer Award, and the Georgia House of Representatives honored him at the state capitol with a resolution acknowledging his accomplishments. All of these recognitions were gratifying to Red, who was genuinely appreciative in accepting the accolades. Only in recent years has he come to grips with the fact that he is truly deserving of the awards.

The honor that was most personally fulfilling for him came when he was inducted into the Atlanta Sports Hall of Fame in 2006. When he received the call informing him of his election, Red shouted with joy. “I was so elated, I just shouted,” he explained. “I’m living and I can get to smell the roses. I’m glad that I will be able to do that. A lot of time some of us get awards and everything after we’re already gone.”

JIM RILEY, the author of six books, including “The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues” (Da Capo Press, 2002), is research director of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum. He has contributed to “The ESPN Baseball Encyclopedia” and the official program of the Major League Baseball All-Star Game.

Sources

The information for this article came primarily from the author’s interviews with Red Moore, Roy Campanella, Ray Dandridge, Leon Day, Monte Irvin, Buck O’Neil, Ted Radcliffe, and Willie Wells.