Remembering the 1951 Hazard Bombers

This article was written by Sam Zygner

This article was published in Fall 2015 Baseball Research Journal

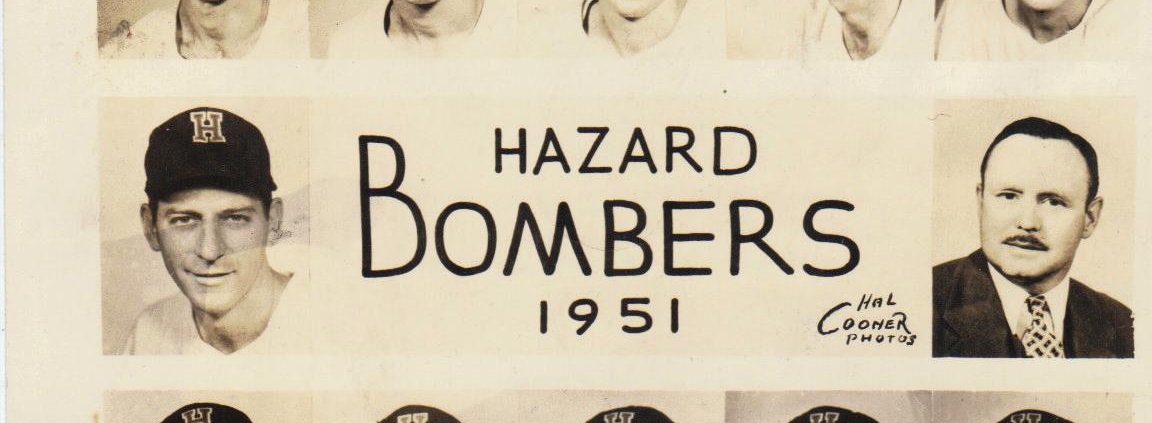

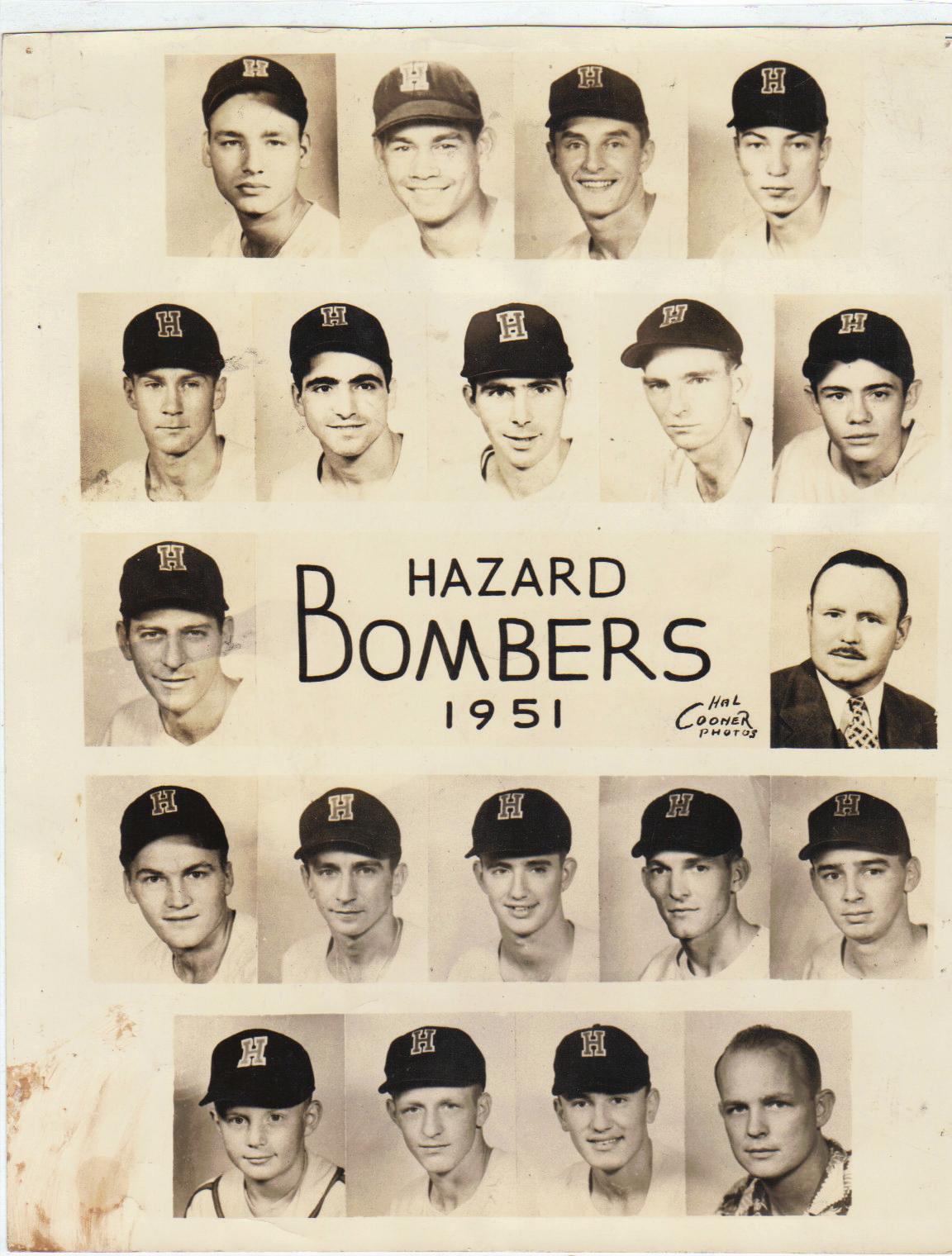

1951 Hazard Bombers. From L-R, top row: J. Ravelo, D. Hayling, E. Bobrik, J. Podres. Second row: K. Johnson, R. Coluni, L. Isert, M. Sanders, R. Torres. Third row: M. Macon, Max Smith (team owner). Fourth row: R. Dacko, J. Tondora, J. Chapman, K. Cox, E. Catlett. Bottom row: C, Crook Jr. (batboy), H. Snyder, T. Kazek, B. Mansfield (business manager). (Courtesy of the Bobby Davis Museum)

Nestled in Perry County in southeast Kentucky—the heart of the Appalachian coal country—lays the quaint city of Hazard, population just over 4,400 souls. The county and the city are named for Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry, a naval commander during the War of 1812. At the Battle of Lake Erie, he uttered the famous words, “Don’t give up the ship,” and, “We have met the enemy and they are ours.”1 The same pugnacious spirit that characterized Perry was also reflected in a group of young minor league ballplayers who in 1951 captured not only the hearts of their community, but a Mountain States League pennant.

Even today, locals still talk about the magical season. They recount the exploits of an upcoming Brooklyn Dodger pitching star, a Costa Rican flame-thrower who dealt with blatant racial prejudice, and a determined, hard-hitting player-manager who led the team to one of the all-time great seasons in minor league history. They were known as the Hazard Bombers.

Bombers Take Flight

As World War II came to an end, life in America returned to normality. Servicemen left the horrors of war behind with a sanguine eye to the future. They also sought the need for entertainment, and a reconnection with our national pastime.

Minor league baseball, like many things, had been severely curtailed during the hostilities due to manpower shortages. As an example, in 1944 only ten leagues were operating. Following the war, circumstances changed dramatically and minor league baseball experienced a period of unprecedented growth.

By 1948, there were 58 officially recognized leagues including the spanking new Class-D Mountain States League, formally organized on February 1, 1948. The original MSL lineup consisted of towns in eastern Tennessee and southwest Virginia and Kentucky and featured a 120-game schedule beginning on April 29.2 Although Hazard was not part of the original circuit, that soon changed.

When the first week of June 1948, rolled around, the Oak Ridge Bombers were leading the league in the standings, but struggling to draw fans through the gates. Grasping the opportunity to bring baseball to his hometown Hazard, the ambitious owner of the Mary Gail mine, Max Smith, purchased the struggling Oak Ridge club and relocated them.3 The Bombers (65–43) were an instant success and finished their first campaign in second place. They nearly took the championship before falling to the Morristown Red Sox in the finals, three games to two.4

There were high expectations going into the 1949 season, but the outcome was very disappointing to Hazard supporters. The Bombers (35–89) sank to the bottom of the standings, finishing 48 games behind the first-place Harlan Smokies. Especially upsetting to Smith and the local fandom was the success of their biggest rival, the Smokies, who cruised through the postseason and captured the league crown.5

Smith was determined that there would not be a repeat of 1949. His first move was signing a new manager. He found his man in former major leaguer Max Macon and inked him to a two-year contract to serve as a player-manager. Macon, the one-time St. Louis Cardinal (1938) and Brooklyn Dodger pitcher (1940, 1942–43), was known for his “never-give-up” attitude. After his arm gave out, he re-invented himself as a first baseman with the 1944 Boston Braves. His last appearance in the big leagues was on April 17, 1947, after which he spent the rest of the season with the Braves American Association Triple-A affiliate in Milwaukee.6 He was hired for his first managerial job with the Modesto Reds of the Class-C California League in 1949.7 Despite a losing record of 54–85, he proved himself a capable leader, and could still swing a productive bat coming off a season in which the left-handed thumper hit .383 and slugged five home runs in 107 games.8

The 1951 Season

In 1950, the Bombers’ fortunes turned for the better. Under Macon’s guidance, Hazard (76–49) finished in second place, five games behind the league champions, Harlan. Macon won the batting crown with a .392 average and the club drew a league-leading 55,184 in attendance. Although they were eliminated in the playoffs by Middlesboro, three games to none, the outlook for the 1951 season was promising.9

A key to Macon’s success was his strong relationship with the Dodgers. He was able to partner Hazard with the big league club which provided him a pipeline of top-flight talent. Hazard was the only team in the MSL with a major league affiliation. Moreover, during spring training at Vero Beach, he was able to scout several young prospects. Many of these players were handpicked by him and played vital roles in the team’s success. One pitcher who made a positive impression, and would make his mark during the 1951 campaign, was a tall, imposing right-hander from Port Limon, Costa Rica, Danny Hayling.

In order to steady his inexperienced stable of young arms, Macon recruited a veteran catcher, Lou Isert, who also served as his assistant coach. Isert already had six seasons under his belt in the lower minor leagues, having risen as high as the Class-B Southeastern League.10 During the course of the year, the veteran backstop proved invaluable to his manager as one of his best hitters and capable right-hand man.

Macon was confident his team was a champion-ship club going into his second season. Many prognosticators like Middlesboro Daily News columnist Julian Pitzer agreed and wrote, “Hazard has the advantage of its working agreement with the Dodgers of Brooklyn. Therefore, this might be the year when the Bombers make the grade. That’s our reason for giving them first.”11

The team opened the season at aptly named Bomber Field. The ballpark had been built by team owner Smith prior to the 1950 season and featured box seats, reserved seats, and a roof which partially covered the grandstand. The evening of April 29 was especially exciting for local fans since the hometown team kicked off the season against their nemesis, Harlan. The Bombers took the field decked out in their home white uniforms with blue numbers trimmed with red piping, spanking new red, white, and blue striped stirrup socks, and blue caps featuring a prominent red “H” outlined in white. All eyes were on the field as the 1,638 fans got accustomed to a host of new faces.12 The only three returnees from the previous season were Macon, outfielder Ken Cox, and infielder Ralph Torres.

As his opening night starter, Macon chose 19-year-old Juan Jose (Ravelo) Torres. The Cuban right-hander had struck out 12 in an exhibition game against Middlesboro a few nights earlier, impressing his skipper. Ravelo repeated with another dominating performance, silencing the Smokies’ hitters by allowing only two batters to reach base on free passes and none by base hit. It was a grand start for the rookie, hurling a no-hitter in his professional debut. The final score showed Hazard 10 Harlan 0.13

The Bombers continued to play well during the early part of the season. Ravelo nearly repeated his previous performance by shutting out the Big Stone Gap Rebels, 10–0, this time allowing three hits.14, 15 Hazard opened the season with a six-game winning streak before Ravelo finally faltered, dropping a decision to Harlan on May 7 by the score of 6–3.

Through the month of May, Hazard jockeyed for the MSL’s top spot with Morristown and Harlan. Although Ravelo drew a great deal of early attention for his pitching prowess, his mound mate Hayling, who had so impressed Macon during spring training, was quietly building what turned out to be a record-breaking season. By month’s end the 6’3″ Costa Rican fire-baller sported a glossy 7–0 record, including his first shutout against the Norton Braves on May 24.

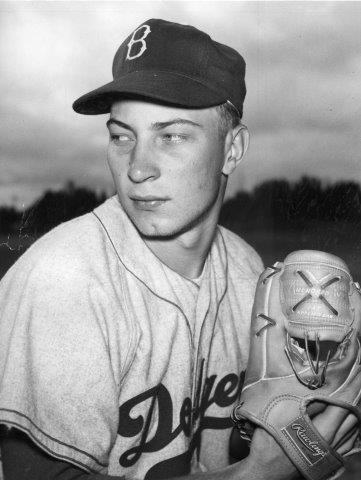

Macon, with an eye on improving his club, received additional help in May with the arrival of pitcher John Joseph Podres. Born and raised in Witherbee, New York, “Johnny” as his friends called him, enjoyed hunting and fishing in his beloved Adirondack Mountains, playing baseball, and following the Brooklyn Dodgers. He realized his childhood dream when he was signed out of Mineville High School by Brooklyn in 1951. Pat Salerno Jr. remembers his father competing against Podres in high school and shared one of his dad’s memories of the future big leaguer in Adirondack Life: “So he would go to his room, turn the radio on and listen to Brooklyn Dodgers games…At 13 and 14 years old, all he wanted to be was a Brooklyn Dodger. He was a small-town boy who made it big.”16 Podres became a legend after earning the win in the deciding seventh game of the 1955 World Series, defeating the New York Yankees, 2–0, helping bringing “Dem Bums” their only world championship while in Brooklyn.

Left-handed Johny Podres would eventually be a World Series hero for the Dodgers, but in 1951 he was fresh out of high school and after struggling at Class B was shipped down to Class D Hazard. (National Baseball Hall of Fame Library)

An immensely talented left-hander with a blazing fastball, Podres began the year at Class-B Newport News. However, his struggles getting batters out consistently and need to strengthen some baseball fundamentals prompted the parent club to make a move. Podres had a record of 0–2 and 5.72 ERA in seven appearances, when the Dodgers brass felt that demoting him to Class-D ball would help him gain confidence. Bob York, who worked for the Bombers in various capacities, remembers how Podres was “a little green” when he first arrived, and how he received instant coaching from Macon.

“I remember Max Macon. Johnny Podres refused to get in front of a ball hit back through the mound. And one of the funniest things was Max Macon went and got a bat and made Podres stand on that mound and he hit those balls right back through the middle, over that mound, and Podres was just terrified.”17

On May 21, Podres made his first start against Big Stone Gap and it wasn’t pretty. Teammate Ed Bobrik recounted his roommate’s inauspicious debut.

A few weeks later a fellow by the name of Johnny Podres reached our club and Max puts him with me, and we roomed together. Podres was pitching, and the score after the first inning was ten to nothing in favor of the other team…He comes back to the bench at the end of the inning and says, “Jesus, I don’t know what’s going on…Gee, I don’t know what’s wrong with me.”

Well, listen. Next time you go out don’t be throwing fastballs all the time. Mix them up. Throw some slow curves and stuff like that. Well, he did and he shut them out the rest of the way.18

Hazard came back to win the game, 12–11. Podres’s second appearance of the year was in relief against Middlesboro during a May 27 doubleheader, where he earned his second victory. He then followed up with another decision against the Norton Braves two days later during a 7–6 win. From that point on, Podres was nearly unhittable. “He was the first left-hander I ever saw that could throw where he was looking,” said teammate George McDuff. “Most of them looked where they threw. But he had control.”19

Following a May 26 loss to Middlesboro, Hazard stood at 17–8. The Bombers then went on a tear, winning 31 of 36 games. By July 2, Hazard stood at 48–13, five games ahead of Harlan. Fueled by the dominant performances of Podres (10–1) and Hayling (16–0), and excellent work from Bobrik (7–2) and Ravelo (10–3),20 Hazard boasted the league’s top staff. In addition, the Bombers were hitting .300 as a group including: Macon (.395), James Blaylock (.356), Donald Hilbert (.329), and John Tondora (.324).21 It was amazing that the Smokies were as close as they were in the pennant race.

Hayling picked up his seventeenth consecutive win on July 10 in a slugfest victory over the Middlesboro Athletics, 12–10. It looked as though the A’s were going to end Hayling’s skein at 16 games after staking themselves to a 10–7 lead going into the eighth inning. Not a team to throw in the towel, the Bombers lived up to their name, exploding for five late runs to overcome the deficit.22 Although not a gem by pitching standards, the big Costa Rican with the unruly fastball that did not always go where directed was thankful for the more than ample run support from the league’s most potent offense.

After 18 straight wins, Hayling’s remarkable win streak came to an end. On July 16, Hazard won the first game of a doubleheader, topping Pennington Gap, 3–1. The second game was a polar opposite slugfest, and Macon called on Hayling for late inning relief with his charges holding onto a one run lead. The Miners were not to be denied and came back to win the game, 13–11, sending Hayling to the showers.23

Except for his teammates and a few front office personnel, the darker-skinned Hayling faced discrimination throughout the season for being perceived as black. The pressure to keep his winning streak alive was nerve-racking, but it paled in comparison to the hurt he felt being the target of prejudicial slurs and verbal threats throughout the league by opposition fans and players alike that were still entrenched in bigotry and the old “Jim Crow” way of thinking. Changes relating to racial bias were slow in coming to this area of the country and it was not until the beginning of the 1951 season that the first black ballplayer, Bob Bowman of Middlesboro, crossed the color line in the MSL, four years after Jackie Robinson’s debut with the Dodgers.24 In spite of the harassment, Hayling maintained a positive attitude and displayed an extraordinary amount of intestinal fortitude in the face of adversity.

McDuff, who speaks with a smooth Texas drawl and was a fellow hurler, had only a month-long stay in Hazard, yet he struck up an instant friendship with Hayling. He witnessed a frightening example of intimidation handed out to his teammate by a narrow-minded baseball fan that occurred after a game in which Hayling had hit an opposing batter with an errant pitch.

He hit that boy in the head and put him in the hospital. So, he was in a coma for several days. He was in the hospital two or three weeks.

And boy it was bad news. I remember going in and Danny and I, we were walking pretty close together. A guy butted in between me and Hayling and he said, “Hayling, are you going to pitch tonight?”

And he [Hayling] said, “No.”

So he said, “Well, you better not get over the coaches line because I’ll be there on that little nob” There was a little hill over there by center field. He says, “I’ll be over there with my rifle and if you get on out of the coaches box, I’m going to pick you off.”

Apparently word got out to the local fans about the trouble Hayling was facing…I know when we were getting ready to go and there were two men who walked up in suits and they were talking to Macon.

“We understand there is going to be trouble up there tonight.” And they said, “If there’s trouble you all just stay in the dugout because there are about two other of us that have tickets and we’ll be scattered out through the stands.”

And he pulled his coat back and he had a shoulder holster with a pistol. And he said, “If there’s any trouble we’ll settle it.”25

On the other hand, the Hazard community warmly embraced the big right-hander with the same gusto as the rest of the Bombers. He was accepted as one of their own.

Many of the players interacted with folks in the community. During the club’s off time the popular hangouts for the team were Don’s Restaurant, the drugstore, and the local pool hall where fans went, hoping to socialize with the Bombers. Bobrik remembered how supportive everyone in Hazard was and with a chuckle in his voice exclaimed, “If we played a game in town, and if you were the winning pitcher, you got a free steak dinner at one of the drug stores, and you would get a free shirt from one of the clothing stores.”26

Hayling, who was one of the best-fed players, reached the twenty-win milestone on July 26, defeating Big Stone Gap, 9–7, putting the Bombers 5½ games ahead of surging second-place Morristown. The same day, Earl Catlett and Joseph Chapman were purchased from the last place Jenkins Cavaliers,27and joined recently signed 18-year-old Dodger prospect, pitcher Theodore “Ted” Kazek, as insurance for the pennant race.28 Not done dealing, Smith also acquired Battle “Bones” Sanders from rival Harlan in early August.29 Sanders, was one of two managers piloting the Smokies during the season and was their best hitter. He had played three seasons with the San Francisco Seals of the Pacific Coast League 1945–47, batting .310 in 107 games in 1945.30 Sanders finished the MSL season belting 25 homers and driving in 132 runs.31 Although not documented, it is suspected that Harlan was shedding its best player over financial concerns.

On August 25, Podres won his twentieth game of the season and clinched the pennant as the Bombers edged Pennington Gap, 4–2.32 With the last out, all of the Hazard squad swarmed the field in celebration. Macon declared that he received so many handshakes and slaps on the back that it felt like he had been in a brawl. The Bombers must have partied pretty hard that night as the next day the Norton Braves laid a thumping on Hazard starting pitcher Hallard Snyder and his teammates, to the tune of 25–4.

By the season’s conclusion, Podres had garnered his twenty-first win and Hayling his twenty-fourth. Podres led the league in strikeouts with 228, in ERA at 1.67, and win percentage at .875. Hayling finished with the most wins and tied Podres for most shutouts with four. Bobrik (12-3) finished third in the league in ERA at 2.84.33

On the offensive side, Macon finished fourth in the race for the batting title, hitting .409. Astonishingly, he was second on his own team to Ken Cox, who in 72 games batted a glossy .415. Both Bombers were outdistanced by Orville Kitts of Morristown, who had an impressive .424 batting average. Macon had one consolation; he led the league in RBIs with 148.34

Final standings

| W | L | GB | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard Bombers | 93 | 33 | — |

| Morristown Red Sox | 86 | 39 | 6.5 |

| Harlan Smokies | 82 | 43 | 10.5 |

| Middlesboro Athletics | 59 | 66 | 33.5 |

| Pennington Gap Miners | 54 | 71 | 38.5 |

| Norton Braves | 53 | 72 | 39.5 |

| Big Stone Gap Rebels | 49 | 75 | 43 |

| Jenkins Cavaliers | 24 | 101 | 68.5 |

MSL Playoffs

In the opening round of the playoffs, Hazard squared off against Harlan in a best-of-five format. As expected, the series featured a high degree of competitiveness as tempers flared during every game. However, the Bombers were not to be denied and swept the Smokies in three games. In the final contest, Hayling and Podres teamed up to win a 9–8 slugfest. Macon led the attack, driving in four runs, and the fiery Isert plated three.35 In her book Ball, Bat, and Bitumen, L.M. Sutter shared an incident defining just how competitive the rivalry was:

Harlan manager John Streza was at bat and after being driven back by two inside pitches, claimed the Hazard hurler was throwing at him. Streza got on first and there made a derogatory racial statement with reference to the Hazard club. After the inning, Lou Isert, on his way to the third base coaching box, passed Streza and told him, ‘[Y]ou’d be afraid to make that statement in our ballpark.’ Heated words ensued between the two and Streza is said to have held Isert by his hair and kicked him with his knee several times before the fray was broken up. Both players were ejected from the game.

Having dispatched the Smokies, Macon set his eyes on Morristown for the MSL title. In game one of the best of five, Podres was masterful, striking out 13 Red Sox. Robert McNeil, who had won 17 games during the regular season, was almost as good, collecting 12 whiff victims. But, in the tenth inning, the game winner came when Joe Chapman tripled and scored when Sanders drove him in.36

Game two pitted Kazek (4–3, 7.44) against Porter Witt (21–5, 2.84). After falling behind 4–1 in the first inning, Macon replaced his starter with Snyder, who kept Morristown in check the rest of the way. The Bombers scored once in the fourth, and three apiece in the fifth and sixth to pull ahead, 8–6. Between Macon’s single, double and home run, which netted five runs batted in, shortstop Robert Coluni’s three base knocks, and Sanders’s four hits, it proved too much offense for their beleaguered opponents as the Bombers pummeled the Red Sox, 13–6.37

Game three was an almost foregone conclusion with Hayling on the hill. Morristown drew 10 walks but mustered only six hits off the big righty, who as usual went the route for the complete game win. Red Sox pitchers gave up 13 free passes and allowed 35-year-old Macon to steal two bases in the Bombers’ 10–3 win. Hazard had its first league championship.38

Macon’s proficiency as a hitter and his ability to motivate his players proved to be a major force in the success of the team. Pitcher Bobrik described his skipper fondly: “He was a quiet man. He didn’t raise a ruckus with us. But, he was manly you know. We were kids and all that, but he was manly to us. He didn’t give us a hard time. He didn’t rant at us, or shout at us. He was low-key and I enjoyed playing for the man. He was really tops in my book. I can’t say enough about him.”39

With Macon’s departure at the close of the season, as well as the absence of the star power of Hayling and Podres, some of the magic that so spellbound the community of Hazard was gone. Increasingly, television was providing a more attractive distraction and the popularity of minor league baseball was in its waning days.

In 1952, Hazard (87–32) nearly repeated its performance, repeating as pennant-winners, this time under manager Mervin Dornburg. The Bombers were knocked out in the playoffs against Morristown, three games to one. Their nemesis, Harlan (73–45), finished the regular season in second place and won the championship, upending Morristown in the finals, three games to none.40 Sadly, it was also Hazard’s last year of minor league ball. Their attendance dipped to 14,600 and, due to financial reasons, the team folded.

In 2001, as part of minor league baseball’s 100th anniversary, historians Bill Weiss and Marshall Wright researched and evaluated what they considered the 100 greatest minor league teams of all time. The list includes clubs from every decade of the twentieth century and introduced baseball aficionados to some teams who were otherwise lost to history. Coming in at number 81 were the Hazard Bombers.41

Although professional baseball has never returned to Hazard, old-timers still share their fond memories from that wonderful 1951 season. It was baseball at its best serving as a catalyst for the community by creating a source for local civic pride. The success of Podres and Hayling, especially the latter’s win streak, drew national media attention to an otherwise inconspicuous hamlet in Kentucky. The team’s championship served as the icing on the cake to the greatest team in Mountain States League history.

So, if you ever find yourself driving through Hazard, and are inspired to visit the Bobby Davis Museum on Walnut Street, be sure to stop. Within its walls, in an enclosed glass case, resides an original Bombers uniform worn by batboy Claude Crooke with the number “1.” You will also see two autographed team baseballs, and a black and white photograph featuring each member of the Bombers who brought a championship to a sleepy town in Kentucky, named after a naval commander with the fighting spirit, like the team, that also won the day.

Epilogue

Ed Bobrik pitched only one season of professional baseball. He developed a back condition and was unable to throw a fastball anymore, cutting short his dream of reaching the big leagues. He later worked for the airlines for 37 years in communications, electronics, and mechanics before retiring in Goodyear, Arizona.

Danny Hayling moved up to the Class-A Pueblo Dodgers in 1952, but suffered a broken ankle in June.42 He bounced around the minor leagues for several years without repeating past successes until 1960 when he won 22 games for the Class-D Hickory Rebels of the Western Carolina League.43 He later played in Cuba, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, and Puerto Rico. He received the keys to the city of Hazard, is a member of the Sally League Hall of Fame (1994), and is regarded as the greatest ballplayer to ever come out of Costa Rica. He departed this world on January 14, 2009, in his home country.44

Max Macon moved on to Miami, Florida, for the 1952 season where he became manager of the Class-B Florida International League Miami Sun Sox. Once again, he proved a capable player-manager, leading the Sun Sox to the pennant and league championship in a tightly fought race with the Miami Beach Flamingos. He remained a skipper in the minor leagues until 1963 and finished his career for Class-A Jamestown in the New York-Pennsylvania League. His lifetime mark was 1,100–949, including stops at Triple-A Montreal of the International League, and St. Paul of the American Association. Macon died on August 5, 1989, in Jupiter, Florida.45

George McDuff finished the season with two wins and two losses in 44 innings. He also pitched in the mid-season Mountain States League All-Star game, but unfortunately took the loss. The 6’2″ Texan pitched for four seasons in the minor leagues with stops in Lubbock in the Class-C West Texas-New Mexico League (1952, 1954, and 1955), and Class-B Big State League in Austin (1955). He currently resides in Lubbock and is still active in his landscaping business. He and his wife Beverly are avid Texas Tech sports supporters.

Johnny Podres went on to a successful career as a major league pitcher. Long-suffering Brooklyn Dodger fans will always remember him as the one who ended the cries of, “Wait ’til next year.” Over the course of his 15-year career, mostly with the Dodgers, then the Detroit Tigers and San Diego Padres, he won 148 and lost 116 games with a 3.68 ERA. He later became a major league pitching coach for 13 years spending time with the Boston Red Sox, Minnesota Twins, Philadelphia Phillies, and Padres. He passed away on January 13, 2008, in Glens Falls, New York.46

SAM ZYGNER, a SABR member since 1996, is Chairman of the South Florida Chapter and author of The Forgotten Marlins: A Tribute to the 1956–1960 Original Miami Marlins. He received his MBA from Saint Leo University and his writings have appeared in the “Baseball Research Journal,” “The National Pastime,” and “NINE.” A lifelong Pittsburgh Pirates fan, he has shifted his focus to Miami baseball history.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Ed Bobrik, George McDuff, and Bob York for sharing their personal experiences. Also, I am indebted to fellow SABR members William Dunstone, Frank Hamilton, Ed Washuta, and Robert Zwissig for providing invaluable statistical information on the MSL. Thanks to Alberto “Tito” Rondon for his research and input on Danny Hayling. Thank you to Martha Quigley of the Bobby Davis Museum and Ed Bobrik for contributing photographs. And last, but not least, I am grateful to my wife Barbra for her journalistic skills and continuing support in all of my research and writing endeavors.

Notes

1. http://cityofhazard.com/history.html. “History of Hazard and Perry County.” ↵

2. Middlesboro Daily News, “Mt. States Champs Lose 10–0 Game In Opener,” 4. ↵

3. L.M. Sutter, Ball, Bat, and Bitumen: A History of Coalfield Baseball in the Appalachian South (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co. Inc., 2009), 130. ↵

4. http://baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Mountain_States_League. Accessed April 22, 2015. ↵

5. Ibid. Harlan (83–41) won the regular season pennant and the league championship defeating Morristown three games to two. ↵

6. Baseball-Reference.com ↵

7. Ibid. Macon was 4–11 during his rookie season with a 4.11 ERA and was used more as a reliever than a starter. In three seasons he was with Brooklyn he was 13–8, in a similar role, with a 4.47 ERA. Nineteen-forty-four was his best season as a hitter in a Boston Braves uniform batting .273, with three home runs and 36 RBI’s. ↵

8. http://californialeague.webs.com/seasons/1949.pdf. Accessed April 22, 2015. ↵

9. Baseball-Reference.com, “Mountain States League History.” ↵

10.Baseball-Reference.com. Isert played for Class-D Thomasville and Albany of the Georgia-Florida League (1940), Class-D Greeneville of Appalachian League and Class-D Owensboro of the Kentucky-Illinois-Tennessee League (1941), Class-D Centreville of the Eastern Shore League (1946), Class-D Natchez of the Evangeline League (1947), Class-B Gadsden and Anniston of the Southeastern League (1947), Class-B Vicksburg of the Southeastern League (1948), and Class-C Lafayette of the Evangeline League (1949) prior to landing in Hazard. ↵

11.Julian Pitzer, “Sport Slants,” Middlesboro Daily News, April 28, 1951, 4. ↵

12.Middlesboro Daily News, “Mt. States Champs Lose 10–0 Game In Opener,” 4. ↵

13.The Sporting News, “Ravelo Tosses a No-Hitter In Mountain States Opener,” May 9, 1951, 32. ↵

14.Middlesboro Daily News, “Morristown Scores Fifth Straight Win,” 6. ↵

15.The Sporting News, “Coastal Plain Has 7 New Pilots,” May 16, 1951, 33. ↵

16.Paul Post, “From Mineville High to the Majors,” Adirondack Life,October, 2013. ↵

17.Bob York, telephone interview, April 6, 2015. ↵

18.Ed Bobrik, telephone interview, March 19, 2015. ↵

19.George McDuff, telephone interview, April 2, 2015. ↵

20.The Sporting News, July 18, 1951, 32. ↵

21.Middlesboro Daily News, “Mountain States League Leaders,” July 3, 1951, 2. ↵

22.Middlesboro Daily News, “Hayling Chalks Up 17th Consecutive Win For Hazard,” July 11, 1951, 4. ↵

23.The Sporting News, “Rookie Sets Hurling Record,” July 25, 1951, 38. ↵

24.The Sporting News, “First Negro to Join O.B. Club in Dixie Makes Debut,” May 16, 1951, 32. ↵

25.George McDuff, telephone interview, April 2, 2015. ↵

26.Ed Bobrik, telephone interview, March 19, 2015. ↵

27.Julian Pitzer, “Sport Slants,” Middlesboro Daily News, July 27, 1951, 8. ↵

28. The Sporting News, August 1, 1951, 32. ↵

29. L.M. Sutter, Ball, Bat, and Bitumen: A History of Coalfield Baseball in the Appalachian South (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co. Inc., 2009), 133–34. ↵

30. Baseball-Reference.com ↵

31. 1952 Sporting News Guide, 449. ↵

32. The Sporting News, “Late Change In Managers,” September 5, 1951, 36. ↵

33. 1952 Sporting News Guide, 453. ↵

34. 1952 Sporting News Guide, 448. ↵

35. Middlesboro Daily News, “Hazard Tops Harlan Three Straight,” September 4, 1951, 4. ↵

36. Middlesboro Daily News, “Hazard Wins 1st Playoff Game 2–1,” September 6, 1951, 6. ↵

37. Middlesboro Daily News, “Hazard Win No. 2 In Playoff Finals,” September 7, 1951, 4. ↵

38. Middlesboro Daily News, “Hazard Wins 3rd Straight Over Morristown To End Mountain States Season,” September 8, 1951, 4. ↵

39. Ed Bobrik, telephone interview, March 19, 2015. ↵

40. Baseball-Reference.com ↵

41. http://milb.com/milb/history/top100.jsp ↵

42. The Sporting News, June 25, 1952, 34. ↵

43. Baseball-Reference.com ↵

44. http://nacion.com/obituario, “El ultimo out del Duque de Hazard,” January 15, 2009. Retrieved April 23, 2015. Thanks to Barbra Zygner and Tito Rondon for providing the translation into English. ↵

45. Baseball-Reference.com. Also added on was Macon’s record at Modesto which wasn’t included on his lifetime stats. ↵

46. Baseball-Reference.com. ↵