Replay Behind The Scenes — At The Ballpark

This article was written by Bill Nowlin

This article was published in The SABR Book of Umpires and Umpiring (2017)

ANDY ANDRES, FIELD TIMING COORDINATOR

Interview on August 17, 2015

MLB approved replay and tested it out in the Arizona Fall League of 2013. In spring training 2014 they had all the technical stuff worked out, but when the broadcasters came in they realized the producers can’t decide what to do with the third out. Third out, the regular producer’s got like 10 seconds to wrap up, a minute 45 commercial, 10 seconds to talk, then the game. That’s the producer’s job. But on a third-out close play, the producers are like, “What do we do? Do we wait?” MLB realized they had forgot about that part.

MLB approved replay and tested it out in the Arizona Fall League of 2013. In spring training 2014 they had all the technical stuff worked out, but when the broadcasters came in they realized the producers can’t decide what to do with the third out. Third out, the regular producer’s got like 10 seconds to wrap up, a minute 45 commercial, 10 seconds to talk, then the game. That’s the producer’s job. But on a third-out close play, the producers are like, “What do we do? Do we wait?” MLB realized they had forgot about that part.

So they hired Field Timing Coordinators to make the decision to go to commercial break or not. We watch the third out and both managers, to make the right decision. We also did clock management between innings. The umpires weren’t supposed to start a pitch before we let them know. We had to coordinate with them. The original idea was that we would actually stand on the field with our own stopwatches and flash different colored cards—”go” or “don’t go.” Green was “go ahead.” All 30 parks had a different spot, but we were all on the field. They backed off on that, so we were put just near the field, in the third-base photo well. The umpires were supposed to watch us. They hated it. They didn’t want to do that. They were resistant. But then the Commissioner laid down the law and so they finally sort of got on board. Now, instead of flashing cards we operate the clock out of the press box.

The Commissioner really wants a 20-second pitch clock to increase the pace of play. Right now, it’s happening in Double A and Triple A and there’s a real move to make that happen in major-league baseball. It’s going to have to be negotiated, bargained between the owners and the players, but I give it a pretty high probability that it’s going to happen because the lords of baseball want it to happen. It’ll speed up the game. If it happens, the clock operator will be a part of that and become an official of the game.

I can see Dan Fish right now. He’s the Replay Headset Coordinator. His whole job is to set up the headsets, make sure they’re connected with the replay center in New York. There’s an umpire crew there. The umpires know to look there if there’s a replay in Fenway, and Dan’s supposed to pop out and hand them headsets. Everyone’s supposed to be connected. Last year, I was connected with the umpire headset chatter. I could hear them. There’s usually one guy in New York as the talker. Last year we heard the chatter. They told us very clearly we’re not supposed to talk about what was said.

Dan pops out with the headsets and make sure the umpires could chat with New York. The replay rules are very specific. Call/not call. Who calls it when. The umpire crew on a challenge play.

Two guys always come over and they both get on the headsets. I think that’s just redundancy so there’s no screw-ups. I think baseball’s very happy with replay. They see that peoples’ interest spikes up. I think the time taken in replay is balanced by the time taken in arguing.

[One or two managers have been ejected for arguing a replay decision.] I think Scioscia was. Replay went against him, and he just kept railing and railing. His justification was, “I had to get a ruling, in case I have to protest.” He had to know what the ruling was. That’s how he justified his argument, that he needed a ruling for protest purposes. He was demonstratively vehement in his request for a ruling.

[There have been calls for replay even in the first inning.] The logic on that begins with the question: How many close plays are there in a game? If there’s one, even if it happens in the first inning, you shouldn’t not challenge just because you want to lose a challenge.

There’s probabilities in all of these things. Everyone’s measuring the probability of it being successful. I think there are fewer than one challenge per game, per team, which means “use it when you think you’re close.” If it’s half a challenge per game, per team, when you get anything close, your probabilities go the other way. You should use it. If you do get screwed occasionally, it just happens. I’m sure someone has already analyzed how many challenges you can’t make because you’ve already lost your right to challenge. I bet it’s pretty infrequent.

If it’s the seventh inning and you have a 10% likelihood of winning that challenge, I can see rolling the dice.

Dan Brooks and Harry Pavlidis, I think, wrote an article in spring 2014 about the strategy of calling a challenge from the manager’s perspective.

With the emergence of PitchFX, fundamentally, if you think about the event of the pitch, there are four players — umpire, catcher, batter, and pitcher. And they all have their own strike zone. That’s not so clear to people. People think it’s just “the strike zone.”

The batter has a strike zone and there are tendencies there as to what gets called strikes for that batter. The pitcher has a strike zone. The catcher has a strike zone; that’s “framing.” Umpires obviously have a strike zone. You can evaluate each of those four impacts on the strike zone. If a pitch is here [indicates], that’s probably going to be a strike if you know those pitcher/catcher/batter/umpire, you kind of know those probabilities.

When QuesTec came in, slowly but surely, the umpires’ strike zones started conforming. Before that they were like…every guy was… all over the place.

Every game, they get a report. A disc that shows every one that they missed, or that they got.

I don’t see the three-dimensional stuff here. But one thing to remember when you see the strike zone on Gameday or TV, you don’t see the three‐dimensional zone. If you’re just looking at two dimensions, you’re not seeing the full strike zone. If you’re just looking at two dimensions, you’re not seeing the full strike zone.

The real key is where the strike zone moved vertically. The guys in the PitchFX truck…MLB is telling them how to do it and that’s driving the strike zone. The umpire gets a report, and he goes, “I’ve got to do this because this is what MLB is grading me on.” Slowly but surely, umpires became more consistent vertically.

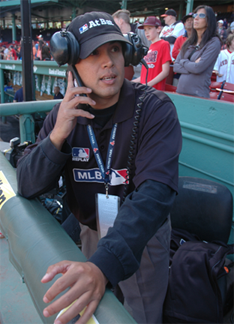

DAN FISH, REPLAY HEADSET COORDINATOR

Interview with Dan Fish, Replay Headset Coordinator, September 2, 2015

I worked the first games of replay here. I got the job through the military. I serve in the Reserves and one month while I was at drill, a representative from the Hero2Hired website came in and talk to our unit. I told her I was extremely interested and passionate about baseball, so she forwarded my information to MLB Network. A few weeks later I got a call from Erika Brockington in New York, the manager for MLB, and here I am today, lucky enough to still be working with them.

I worked the first games of replay here. I got the job through the military. I serve in the Reserves and one month while I was at drill, a representative from the Hero2Hired website came in and talk to our unit. I told her I was extremely interested and passionate about baseball, so she forwarded my information to MLB Network. A few weeks later I got a call from Erika Brockington in New York, the manager for MLB, and here I am today, lucky enough to still be working with them.

I commute from East Brookfield, about 20 minutes away from the city of Worcester. I did most of the games last year and I’ve got about 50, 55 games this year so far, more than half. I split it with two other people. It’s hourly pay. We get paid biweekly.

I usually get here at least three hours before the first pitch, get the headsets, and hook them up. They used to be in the umpires room, but we moved them to our little storage room known as the “hut,” because it’s a little easier to get to. It is where we keep all our camera stands, tripods, and other stuff we need for the day. I hook up the headsets, make sure they’re all working. If the headset weren’t working, the umpires would use the “legacy” backup set in the umpires room. One time, for some reason, it took a minute for the people in New York to respond. I was about to tell the umpires to go down to the legacy room. I was kind of nervous for a few seconds, didn’t know what was going on, but then all of a sudden the people in New York started talking. It was a close call.

Before every series that I work, about 15 minutes before the first pitch, I go into the umpires room, introduce myself, let them know where I’m going to be standing so there’s no confusion. I pay attention to the game. If it’s a close call, I get a good idea if they’re going to challenge it. If the umps flag me down, I’ll just hop over the railing of the photo well here and give them the headsets. One set is for the crew chief and one is for the umpire whose call is challenged, unless it’s the crew chief’s call which is being challenged and then it’s the number two man. I can’t hear anything.

I really enjoy just being around the park, and the atmosphere. Being involved, seeing the professionals work to get better at what they do. Sometimes it’s hot and sometimes it’s cold, or raining. Have I ever had fans give me a hard time? I have, actually. Whenever a call doesn’t go the Red Sox’ way, the fans will boo me a few times.

But it’s a great job for a baseball fan, someone who really enjoys baseball the way I do. I think it’s a great opportunity, starting-wise. We have a replay tech, and a ballpark cam tech. I check in with the replay cam tech and I give him all my “fax” times – basically just my report times that I check to make sure all the equipment is working (headsets, field timing headset, PA headset, etc.) I think being the headset tech is a good way to get my foot in the door, maybe for some good opportunities in the future.

Being on the field during a game, watching the umpires waiting for a call, I’m trying to think of a word to describe the feeling, and I don’t think I can come up with a word that truly describes how I feel. I remember how nervous I was for my first challenge, and just kept thinking not to screw it up in any way. I feel privileged to be able to be on the field with the best players in the world, and it just amazes me that I have this feeling of such excitement every time I’m out there, and these guys do this every day, 162 games a year. I almost feel like a player walking out with the headsets, and when everyone cheers because the manager challenged a play, that feels like my walk-up music. And I have an awesome view of the games.

JEREMY ALMAZAN, REPLAY HEADSET COORDINATOR

Interview with Jeremy Almazan done September 26, 2015

I grew up as a military kid. I was in the Air Force, a logistician, a 2S-071. Supply. 20 years, one month, seven days. I was stationed various places. I started at Dyess Air Force Base in Abilene, Texas, and I ended at Fort Meade, Maryland. I was at Balad (Iraq) in 2003-2004.

I grew up as a military kid. I was in the Air Force, a logistician, a 2S-071. Supply. 20 years, one month, seven days. I was stationed various places. I started at Dyess Air Force Base in Abilene, Texas, and I ended at Fort Meade, Maryland. I was at Balad (Iraq) in 2003-2004.

I consider myself a baseball junkie. I started on the Washington Nationals grounds crew. I’m a huge Pittsburgh Pirates fan and when they came to Washington last year, I was someplace I wasn’t supposed to be. I snuck into the tunnel behind the dugout and I started bothering the headset people. I was asking them what it was like, how I could get involved. They gave me my boss’s number just to get me to shut up.

This is my first full season. I work for a consulting firm called Chris Fickes Consulting, which is contracted out to MLB. They are based out of Nashville, Tennessee.

I’m like the emergency guy, if they need a fill-in someplace, I’ll go. This is my second series here. I did a series in June.

Love it. We’re required to be here about four hours, but I come a little earlier because I like to have the ballpark to myself. I was an hour and a half early today. I appreciate the history and unless you go to Wrigley Field you can’t get more historic than this. The last time I was here, I went into the Monster wall.

I feel like I’m part of the baseball game. I’ve been a part of baseball history this season. I was here when they had the ambidextrous pitcher (Pat Venditte), and I was the headset tech for the “no fans” game in Baltimore. (April 29, 2015 at Camden Yards, following rioting in the city) Hopefully we don’t ever have to do that again. That was very weird.

Nobody got booed that day.

What I like is just being part of the game. I was lucky to make it into baseball another way. I feel like I’m part of the game. I don’t make the calls. They make the calls in New York.

Replay’s only going to get bigger. It’s in its second year and, in my opinion, still in its infancy. I’m sure we’re going to get some new things. I hope to continue on this path, and be part of it as long as my boss will have me. We don’t get a report card or anything like that but I don’t want to be that guy that sucks, and then somebody says something.

I’m part of a team of three, so there are other positions I could get. One is the instant replay tech, to make sure that all of the camera angles are good, and the other person runs the ballpark cam.

JOHN HERRHOLZ, BALLPARK CAMERA TECHNICIAN

Interview with John Herrholz done on September 27, 2015

I’m the ballpark camera technician. I work for Chris Fickes Consulting. I was on the initial crew that put in the ballpark camera systems here, and I did the one in New York as well, at the old Yankee Stadium. That was done by our consulting team that installed them all for Major League Baseball Network. Following the installation, they said, “Well, OK, now we have to crew this. You’re familiar with the system.” So I got hired. I live north of Boston, in New Hampshire. I’ve worked in this park now for 32 years — local affiliates and all.

I’m the ballpark camera technician. I work for Chris Fickes Consulting. I was on the initial crew that put in the ballpark camera systems here, and I did the one in New York as well, at the old Yankee Stadium. That was done by our consulting team that installed them all for Major League Baseball Network. Following the installation, they said, “Well, OK, now we have to crew this. You’re familiar with the system.” So I got hired. I live north of Boston, in New Hampshire. I’ve worked in this park now for 32 years — local affiliates and all.

The first use of replay was in September 2008, and then we put the actual cameras in during the late spring of ‘09 and that’s when I got involved.

Before 2014, it was almost only fair or foul. At that time, you had only one person — which was me –and you were working both for Major League Baseball Network doing ballpark cam, and for Major League Baseball.com ensuring they had in-bound feeds from the production trucks. That was all they had. It wasn’t divided down into individual camera feeds. It was just a program feed, clean and dirty, with or without graphics, back to Major League Baseball.com. So you were a little bipolar — who are you working for and whose needs are you trying to address? It was a little ugly but we got through it.

Before the game, our job was simply to check out the replay monitor — the “legacy” — and make sure it was switching, make sure the sources were correct back from Major League Baseball.com. It’s the same identical box now, same identical ringdown, all of that. It was more or less, OK, go in and make sure that technically it’s working right. The problem we had was that you were downstream of getting the feeds from the truck set, so if there’s any kind of hiccup with that…. At times that meant if you were delayed in doing that check, the umpires would get a little stress from that.

I’d just find a place inside the park where I’d like to be. You did not have to hang out near the box. There was virtually nothing for us to do except be available by phone should there be a problem.

The umpires would go out to left field, around the back door and then back to the umpires room. But if you’re not at a dead run, that’s time. A huge delay of the game.

It didn’t happen often. And quite frankly what people were looking at from the team vantage point— to say do I have a challenge or I don’t — was much more limited. You didn’t have a bank of monitors of 14 different feeds to look at. It was, OK, from the top step, what do you think? Shall I challenge it or not?

You look at the human-ness of that argument (between a player or coach or manager, and an umpire) where in those days, for me as a fan, wow, there’s somebody who’s really passionate, and to see them go out and speak on behalf of their players, that to me was more exciting. More personal.

Now they get it right. Bring your anger down a little bit. They got it right.

BILL NOWLIN, known to none as “The Old Arbiter” since he has never worked a game behind the plate, still favors the balloon chest protector for its nostalgic aesthetics. Aside from a dozen years as a college professor, his primary life’s work was as a co-founder of Rounder Records (it got him inducted into the Bluegrass Music Hall of Fame). He’s written or edited more than 50 books, mostly on baseball, and has been on the Board of Directors of SABR since the magic Red Sox year of 2004.