Rethinking the Philadelphia Bobbies 1925 Tour in Japan: ‘Embarrassment to the Nation’ or ‘Great Success’?

This article was written by Kat Williams

This article was published in Nichibei Yakyu: US Tours of Japan, 1907-1958

“Crack! The ball hits the bat. Smack! That ball hits Edith Houghton’s waiting glove at short who quickly throws to first to get the batter and all in a twinkling of an eye. These women play the game in a manner that would no doubt delight the heart of many a manager who ever saw them play.”1

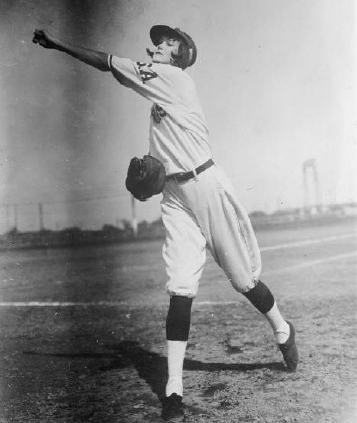

Leona Kearns of the 1925 Philadelphia Bobbies in Japan. (Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-DIG-ggbain-38869)

Writing about a baseball game between the Passaic Girls and the Lansdale Chryslermen, this unnamed reporter was shocked to see women play baseball with talent and dedication. “It was surprising to watch the brand of ball that these girls can play,” he continued. “They take their baseball in a serious way and all the jeering of the “wise guys’ who stand on the sidelines and do the looking on cannot daunt them.” Even the crowd’s “jeers soon turn to cheers when they see the girls in real action.”2 The reporter’s shock at the women’s quality of play was not a new phenomenon. Rather, it echoed hundreds of other local news reports about female baseball players written in sports pages during the early 1920s. Why so shocked? Did they not read each other’s work?

Perhaps it was a lack of public interest in women’s baseball that kept reporters from recognizing a growing trend? But that wasn’t the case. Even reports of large crowds and fervent fans did not stick in the minds of sports reporters. Approximately 1,500 fans showed up to the Lansdale, Pennsylvania, game, roughly 20 percent of the town’s population. Meanwhile, in Maple Shade, New Jersey, the largest crowd of the season came to watch the “famous invading lassies,” the Philadelphia Bobbies, play the local baseball club.3 In that game, shortstop Edith Houghton had five hits, including two doubles and a home run. By this time, the late 1920s, Houghton had been widely written about. She was a standout on the Philadelphia Bobbies team that toured Japan in 1925 and was so well-known that fans in small towns clamored to see her play. There was public interest. Still, in story after story, sports reporters seemed shocked to see women playing baseball at a high level.

Were they skeptical of other reporters’ assessment of good baseball? Some of the language was kind of over the top. In a Philadelphia Inquirer article, “The Quaker City Maids of the Diamond,” Gordon Mackey hailed the play of Edith Houghton and Edith Ruth. “Both members liked to play baseball and they COULD play the game—make no mistake on that score.” In a baseball barnstorming tour their play was legendary but, “like Alexanders in skirts or Hannibals in bloomers, they longed for other worlds to conquer after they had cleaned up most of the alleged sterner sex in duels of the diamond in 1925.”4 Houghton “could play shortstop in a way that would make Joe Boley toss his glove in the air and yell, “bravo,’” and Ruth was “the holder of the initial sack and how she can go after those quick throws and hug that base is nobody’s business.” Team play was also lauded with the same exaggerated language. “What an infield. They work with the rhythm and snappiness that is characteristic of any big-league team.” That over-the-top language—Hannibals in Bloomers and shouts of bravo!—made the players appear aberrant. There is almost a freakshow quality to the enthusiastic description.

Reporters’ continued surprise at women’s good play was most certainly related to the more common descriptions of women’s baseball which emphasized the players’ femininity.” For decades reporters introduced female players as “neat,” “attractive in their uniforms,” and as “spectacles.” They simply skipped over a discussion of their play and instead focused on their appearance, their “dainty hands,” and how it must have been hard for them to hold the glove. They marveled at their “feminine strength” and how hard it must have been to play against “professional strength.” They were used to writing about women who were, in their eyes, not very talented and unwilling to get dirty or to take the game seriously. A report about the Hollywood Bloomer girl team began, “A bevy of beauties from Hollywood, California took time out from powdering their noses and gave a picked team of the Coca Cola Greys the battle of their lives. … The ladies put up a good game but couldn’t stand up under the strain.”5 Even when their play was good and the individual talent exceptional, reporters were still likely to describe games as “an unusual tussle,” played by nine “fair maidens.”6 Most women had been described in these terms for decades. Just because they donned a baseball uniform did not mean that would change.

To reporters and to many men who played, managed, or promoted baseball, there was a set of expectations, standards for play, and a distinct language used to discuss the game and its male players. There were no such expectations or standards for women. As a result, women’s play was judged against that of men, making it difficult for them to be seen as talented players. So they were not. Because it was unfathomable to even think of women in actual baseball terms—a slugger, a hurler, or aggressive on the basepaths—a whole other language emerged to describe women’s baseball. Reporters sprinkled some baseball terms in among talk of their physical appearance—”The longlegged beauty on the third base bag sure can play the hot corner.”7 And because women were used to being described this way they did not resist. They just kept playing.

Women’s insistence on playing and the dilemma of reporters tasked with reporting on their games ultimately combined to establish a separate set of standards and expectations for female baseball players. And over time, two separate baseball spheres, one for men and one for women. From our twenty-first-century perspective, we could claim that these gender-specific standards worked against women who sought legitimacy as baseball players. It could be argued that creating separate baseball spheres took agency or control away from women. Nothing could be further from the truth.

Existing in separate spheres was not new to women. They lived, worked, and studied under a different set of standards than men. So it was likely no surprise to them that the same would happen within the game of baseball. As they had always done, though, women never stopped pushing against the boundaries forced upon them. They learned the game, played it, and from within their baseball sphere, they defined for themselves what baseball meant. They set their own standards and, most significantly, they defined baseball success in their own terms. As it was for men, winning games, playing well, and making money were all part of women’s definition of success, but that was only the beginning. Baseball was an opportunity, a new experience, and a location where women could excel in an endeavor previously off-limits to them. Playing the game provided women with a chance to see the country and ultimately the world. It allowed them to make their own money and to realize a sense of independence. To many players, success was found in the opportunities baseball afforded them and not only in the box score.

There are many examples to illustrate the ways in which women embraced their separate baseball sphere and used it to their benefit, but none is more engaging than the story of the Philadelphia Bobbies and their 1925 barnstorming tour of Japan. The Bobbies’ tour provides an opportunity to show how women not only embraced their separate baseball sphere but used it to challenge traditional definitions of baseball success and to define for themselves how and where they fit into the narrative of baseball. The tour shows how one set of baseball standards were used to plan, guide, and then judge the tour, and how another set, the ones defined and accepted by the women themselves, provide a completely different interpretation. One side saw the tour as an unmitigated disaster, while the other saw it as a great success.

***

The Bobbies, named for the popular 1920s haircut “the bob,” were formed in 1922 by Mary O’Gara. The team was made up of young women from around Philadelphia. Edith Houghton’s friend, Edith Ruth, whose nickname was “the original Babe Ruth,” was masterful on the mound. Loretta Jester-Lipski, nicknamed “Sticks,” was best known for her power at the plate, while Nettie Gans was the team’s left fielder. And, of course, there was “The Kid,” Edith Houghton. Houghton was 10 when she joined the team and 13 when the team left for Japan. The other players were less known and likely had less playing experience, but everyone loved being on the diamond. The team played two or three games a week, sometimes against men’s teams and other times taking on nearby Bloomer Girl teams. O’Gara, who was also the manager of the team, usually held out a portion of the ticket sales for herself and paid the players a rate of $5 to $10 per game. Women were making money playing and coaching baseball.

To aid in the team’s growth, O’Gara hired a local booking agent, R.H. Cross, a vaudeville and amusement agency. Entertainment agencies were often the groups setting up exhibition games for women’s baseball teams; this most certainly added to the circus-like atmosphere of many women’s games. The firm scheduled games for the Bobbies against local clubs in the Philadelphia area and eventually in other places such as New Jersey, upstate Pennsylvania, and Pittsburgh. Due to their widespread travel and, most significantly, their outstanding play, within two years the Bobbies were one of the most popular female teams on the East Coast.

Fortunately for the Bobbies, they were reaching that peak just as a shift in public opportunities for women was also taking place. American women were going to college in greater numbers than ever before. They were working, cutting their hair, and, starting in 1920, they were voting. It was the era of a new, more independent woman and women’s baseball was poised to take advantage. Coincidentally, baseball promoters were taking advantage of a worldwide growth in baseball and the simultaneous spread of capitalism. Male professional baseball players began making trips to Japan as early as 1908. Sending American baseball teams on barnstorming tours in Asian countries became profitable for promoters as well as players. It should be no surprise then that an astute Japanese promoter, T. Shima, suggested an all-female barnstorming tour to Japan.8

While baseball had been played in the country since the 1870s, Shima was riding a new wave of baseball popularity in Japan. American barnstorming tours helped to spread excitement about the game throughout Japan and made stars of American baseball teams and players. Even female players such as Edith Houghton, Nettie Gans, and Edith Ruth, who had not played in Asia before, were known baseball celebrities. Japanese women were big fans of the game and made up a significant portion of the crowds who watched American barnstormers. But there were no women’s baseball teams for the Bobbies to play on their tour. They would play against men.

Shima’s first contact in the United States was with Eddie Ainsmith.9 A veteran of barnstorming, Ainsmith was a longtime major-league catcher and a successful promoter, so he was known among Japanese baseball promoters. In 1920 Ainsmith traveled with Herb Hunter on a barnstorming tour of Japan. Because of his previous success in Japan, and despite his having no experience with women’s baseball, he was the first person T. Shima contacted with the idea of an all-women’s barnstorming tour. Ainsmith accepted the offer to organize the tour.

Unfamiliar with women’s baseball but anxious to take advantage of another barnstorming tour, Ainsmith contacted R.H. Cross, the company that booked games for women’s baseball teams. The company introduced Ainsmith to Mary O’Gara. When Ainsmith first approached O’Gara about the trip to Japan, she and the team jumped at the chance. They would play the game they loved, travel to a foreign country, and get paid a great deal of money in the process, a previously unheard-of opportunity for women.

The Japanese promoters, Ainsmith, and O’Gara negotiated the terms and ultimately agreed to a rate of $800 per game for the players and coaches, along with first-class transportation for the players, O’Gara, Ainsmith, and Earl Hamilton, another former major-league player. Transportation and expenses were also paid for Ainsmith’s wife, Loretta, and Hamilton’s wife, Edna. The women served as chaperones for the players. Unlike the male barnstormers, every female baseball team had to travel with chaperones. Even though the 1920s ushered in a modem era for women, one where they had more freedom, it was still frowned upon for women to travel alone.

With the details of the tour settled, O’Gara and the team were ready to begin the trip of a lifetime. On September 23, 1925, they boarded a train in Philadelphia headed for Seattle. The plan was to play games against men’s teams along the way and to meet up with the Ainsmiths and the Hamiltons once they arrived in Seattle. Naturally they had no idea what lay ahead, but their diaries and letters home show they were ready for a level of travel and adventure most women of the time could not imagine. Excitement and opportunity embraced and motivated the players. “We are off at last!” wrote Nettie Gans, the Bobbies’ left fielder, who kept a diary throughout the trip, which provides a valuable insight into the players’ experiences. “Everyone in fine spirits.”10 Spangler highlighted the travel from Philadelphia to Pittsburgh; St. Paul; Great Falls and Whitefish, Montana; Spokane; and finally to Seattle, where the team met Ainsmith and Hamilton and prepared for the final leg of their trip to Japan. On October 6, 1925, Spangler wrote, “Farewell old USA-All aboard for the Orient. Bobbies came on the President Jefferson, First Class!”11

After long, rough days at sea, on October 19, 1925, the SS Thomas Jefferson docked in Yokohama, Japan. The Bobbies were excited to see the city, but apparently not nearly as excited as the city was to see them. Spangler wrote, “We awakened early, passed doctor’s inspection, had about a million pictures taken then walked down the gangplank to Japanese soil!”12 The Bobbies, the Ainsmiths, and the Hamiltons were met by a throng of media and large crowds of curious onlookers. Photographers overwhelmed the girls with requests for photos and interviews. Edith Houghton, the youngest and arguably the best of the players, was a favorite of the Japanese media, who showered her with gifts. Everyone, though, including Ainsmith and Hamilton, was treated as special guests. The welcome was lengthy but “after some time,” Spangler wrote, “we rode jinrikashaws [sic] to the Maranouchoi [Marunouchi] Hotel. We were greeted at the station by boys from the University we are going to play against. Bouquets galore and banners too.”13

The team’s popularity continued throughout the early days of the tour. Even though the Bobbies were not slated to play top-rated or high-quality teams, their first few games in Tokyo drew crowds of more than 20,000 people. Some estimates were as high as 100,000.14 At the Bobbies’ first game, against Nippon University, Tokyo’s mayor, Yoshikoto Nakamura, threw out the first pitch and the crowd was standing room only. Reports of the game must have seemed unusual to the players, since the headlines did not belittle the team or comment on the strain their “feminine energy” must have suffered during the game. The Japan Times reported, “Several thousand fans showed up at the baseball diamond … prepared to look down from the superior height of their sex and giggle gleefully at the attempts of the girls from America to play baseball. … The crowd that came there to laugh and not to see baseball were disappointed.”15 Another headline read, “What Do the Philadelphia Bobbies Look Like?—They Look Like Good Ball Players.”16 These reports could be seen as proof against the idea of separate baseball expectations for men and women. The reality is, however, that in no other country in the world was baseball more tied to masculinity than in the United States. There was no need for Japanese baseball to exist within separate spheres. Japanese women were not traveling the world playing baseball or threatening the masculine ties to the game. The Japanese reports did likely have an impact on the Bobbies, however. Seeing themselves and their play described by the Japanese press (often in English) in terms usually reserved for male baseball players may have contributed to the women’s positive view of the tour and of themselves as ballplayers.

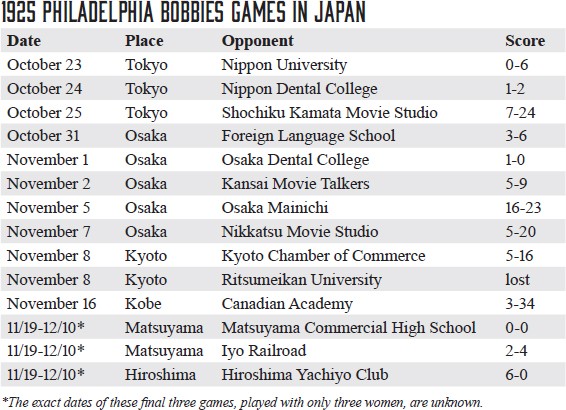

On October 23 the Bobbies played Nippon University and lost 6-0. The next day they played Nippon Dental College and lost 2-1. On October 25 they played and lost their third game, 24-7, against the Shochiku Kamata Movie Studio. The Bobbies played their last game in Tokyo on October 25, losing by a score of 24-7. Again, the Japanese newspapers all but ignored the score and praised the players. The Japan Times reported on “Stick” Jester, Edith Ruth, and Flo Eakin, who, according to the Times, “showed a cool head when she had a man in the hot box between second and first with a man riding third. … [W]hen the man on third [made] a dash for the plate she ripped the ball into the catcher, a splendid throw which Ainsmith fumbled.”17 The Bobbies had been in Japan only 10 days at that point and their adventures were just beginning.

The Bobbies and their entourage left Tokyo on October 29 for Osaka, where they were scheduled to play another round of games. They arrived at the Dobuil Hotel on the night before Halloween, “mischief night.” “We created costumes,” Spangler reported in her diary, and “stood outside the hotel. No doubt the Japanese thought, “what is going on here?’ They don’t celebrate mischief night I guess.”18 The Bobbies were not going to miss an opportunity to celebrate even as they prepared to play baseball the next day. On October 31 they played the Foreign Language School and despite losing the game 6-3, the Bobbies continued to experience the very best Japanese culture had to offer, including the benefit of the doubt from reporters. Because reporters tended to provide little detail about women’s games, we have few specifics about the games themselves. There are very few descriptions of good plays or hits, and other than descriptions of the women or comments about their presence on the field, the only real statistics we have for the games are the final scores.

On November 1 the Bobbies won their first game, 1-0 against Osaka Dental College. The next day they played the actors from the Kansai Movie Talkers, losing 9-5, and on the 5th they lost to Osaka Mainichi Newspaper 23-16. After a day off, the Bobbies played the Nikkatsu Movie Studio on the 7th and the Kyoto Chamber of Commerce on the 8th, losing both games, 20-5 and 16-5 respectively. In the second game of a doubleheader on the 8th, they lost to Ritsumeikan University. On November 16, the day Ainsmith left to start the extended tour in Formosa, the team played the Canadian Academy and lost 34-3. The Bobbies played a high-school team and tied them, and then played two more games, losing to Iyo Railroad, 4-2, and defeating the Hiroshima Yachiyo Club, 6-0.

Like the Japanese newspapers, Spangler’s diary and Leona Kearns’s letters home all but ignore the team’s losses. Spangler’s October 25 entry only mentioned that they had a game, then recalled meeting the “Rudolph Valentino of Japan, a good looking fellow. Some of the girls went over to the Imperial Hotel to see his show.”19 Then on October 26, “We went to a party in the American Embassy, Tokyo, Japan. Each of the Bobbies received a present. Fereba got a beautiful bedspread and pillowcases—beautifully embroidered.”20 In a letter to her parents, Leona Kearns jovially wrote, “We girls are not allowed to drink the water here, so we are going to live on beer.”21 Then later, Kearns declared that “this trip has ruined me. When I get home, I will find myself pressing buttons and ordering my breakfast in bed.”22 On the surface, it seems as though they are feeding a traditional narrative about women not being serious athletes. But there was another layer to this story.

Spangler and Kearns’ focus on events other than those that occurred on the diamond does not mean the team did not take the games seriously or care about the wins and losses. The players wrote a great deal about the game, their individual play and how they had learned from their coaches. “Mr. Hamilton spent a lot of time showing me how to throw a slow ball,” Nellie Kearns wrote in a letter home.23 And Spangler confessed to her diary that the team would have had a better chance to win if “we were faster on the base- paths.” Then she added, “Edith, our shortstop displays her talents beautifully. So does Jenny Phillips.”24 For the women, the play on the field was important and exciting, but playing baseball was about so much more. It was about the opportunities the game afforded them, the experiences and independence they enjoyed because of baseball. “I can’t believe I am in Japan. A farm girl like me,” Kearns wrote to her mother.25 As if to reinforce Leona’s thoughts, Spangler wrote in her diary, “We went to a party at the American Embassy today. Can you imagine?”26 Young women, and especially the mostly working-class women of the Bobbies, would not have been able to imagine such a trip without baseball.

But not everything was positive. There is no indication in Spangler’s diary or other letters written by players that they knew the Bobbies were in financial trouble. But they were and the Japanese media was definitely aware. The first line of a Japan Times article from November 7, 1925, stated, “The Philadelphia Bobbies are in trouble.” After remarking on the team’s lack of money, the reporter offered their low-level play as a reason: “They are a little below the class of a fast Japanese Middle School team and have not been able to meet any teams with whom a game would draw a big crowd.”27 While the Bobbies and their Japanese opponents may have played below a high-school level, this article marks the first time Japanese reporters refer to them in this way.

In Spangler’s November 13 entry we see the first mentions of financial difficulties. “Unlucky 13th, Mary [O’Gara] fell, not too bad. Mr. Ainsmith and Mary discussed going to Formosa with the girls. I believe it has something to do with money being paid. She didn’t want us to go without her although Mr. Ainsmith and Mr. Hamilton had their wives with them. The girl he brought from Chicago went with him as did two of our girls.”28 What Spangler did not know was that the tour was losing money daily. Ticket sales were diminishing, and the Japanese government had decided to tax all future professional baseball games in order to claim a percentage of the receipts.29 These realities dug into the tour’s profits. Then, claiming that they had lost too much money, financial backers simply refused to cover any further expenses. In what was the final straw, the tour’s initial backer, T. Shima, went bankrupt, and two of his promoters disappeared. Ainsmith was made aware of these issues in early November so by the 13th he was clearly seeking alternatives. Having run out of funding, he decided the best option was to push forward with the tour.

Either because he simply had no other choice or because he still believed the venture could be profitable, Ainsmith pushed to expand the tour into Korea, Formosa, and Western Japan rather than end it and return to the United States. Mary O’Gara and most of the players were against Ainsmith’s plan. Having demanded return passage home and been denied by the initial tour’s promoters, the players were leery and refused to play or travel any farther with Ainsmith. He did persuade three of the players, Leona Kearns, Edith Ruth, and Nellie Shank, to accompany him and his wife and (presumably) Hamilton to Korea. To fill out the team, Ainsmith recruited male Japanese players.30

With their promoters and investors gone, O’Gara and the remaining Bobbies were stranded in Kobe. The group’s plight was widely reported in both Japanese and American newspapers. In those reports responsibility for the tour’s failure was broadly assigned. The American newspapers blamed the Japanese promoters for abandoning the Bobbies and the previously complimentary Japanese papers blamed the players and their losses for the tour’s financial problems.31

Despite the shift in reporters’ coverage of the Bobbies and their obvious financial difficulties, neither Spangler’s diary entries nor letters from other players mention fear or uncertainty about their predicament. There are likely multiple reasons for this. As we have seen, the women rarely wrote about negative aspects of the trip, choosing instead to focus on their adventures, Japanese culture, and food. Also, there were a number of people trying to help the Bobbies. The American Consulate tried, unsuccessfully, to secure passage for the women, and an American businessman, Henry Sanborn, who owned a small hotel in Kobe came to their rescue. Sanborn allowed them to stay at his hotel and provided them with meals while trying to raise money for their passage home. The young women no doubt felt anxious about getting back home, but they must also have felt that with so much attention being paid to their story, things would work out.

Things did work out. Due to Sanborn’s diligent efforts a “Mr. N.H.N. Mody, a British-Indian, volunteered to provide funds for their passage home.”32

It wasn’t until Spangler’s November 18 entry, when she wrote, “Fereba and I did sort of a Jumping Jack act up in the hall of the hotel. “We’re Going Home.’ Banzai! (Hurrah in Japanese),” that we see how anxious she was about being stranded.33 Spangler’s excitement when she found out that their trip home has been funded shows her eagerness to leave, but that is the only indication that she or the team was anything other than happy to be playing baseball in Japan.

On November 18, several of the individuals who had assisted the Bobbies bade them farewell as they boarded the Empress of Russia to begin their trip home.34 They spent Thanksgiving on the ship and arrived in Vancouver, British Columbia, on December 1. Five days later, most of the Philadelphia Bobbies returned home to Philadelphia. For O’Gara and the Bobbies who remained with her, their Japanese barnstorming tour was nearly over.

For the seven who set off for Korea, the hardship was to continue, however. Despite a promise to guarantee money for passage to the United States, the Korean promoters reneged on the promise when they realized that Ainsmith’s team had only three girls. With no money to continue, the group was stranded in Hiroshima. As they had done when the initial tour ran out of money, Ainsmith and Hamilton solicited travel funds from other businessmen. The American consul, E.R. Dickover, even tried to help them by reporting the promoters to the police. Nothing worked. With the help of family and friends, Ainsmith was able to secure enough money for his and his wife’s passage, but not for the girls. On December 27, 1925, Eddie and Loretta Ainsmith set sail for home.

Once again Henry Sanborn stepped up to care for stranded Bobbies. Before departing for home, Ainsmith took the girls back to Kobe, where Sanborn agreed to house and feed them while he and others worked to secure their passage home. At Sanborn’s urging, the US State Department negotiated with the Canadian Pacific Steamship Company, which provided passage for the girls. On January 18, 1926, they left Japan aboard the SS Empress of Asia.35

Likely relieved their ordeal was almost over, the girls settled into their quarters. Just a few days into the trip, the ship experienced gale-force winds and heavy snow squalls. All passengers were stuck below deck for safety as the ship tossed back and forth. During a brief calm, Leona Kearns and Nellie Shank went to the deck, despite warnings not to do so. Early in the afternoon on January 21 a large wave crashed into the ship, washing Kearns overboard. The captain was notified immediately and turned the ship around to search for her. The search lasted about an hour but was called off due to low visibility. Leona Kearns was declared lost at sea.36

The tragic death of Leona Kearns brought an end to the badly funded, haphazardly planned, and irresponsibly implemented first-ever all-female barnstorming tour of Japan. Reports of Kearns’ death also set off a set of dueling narratives that described the trip. As the Bobbies’ losing streak grew, fan support dwindled, and Japan’s media got word of their financial situation, some Japanese officials, and even State Department personnel began blaming the Bobbies for its failure. Pointing to the team’s “lack of talent,” American consul Dickover wrote in his 1926 report about the Bobbies’ failures in Japan that it was quickly “apparent that the girls could not play a sufficiently strong game to compete with any school team in Japan.”37

After Kearns’s death, finger-pointing began between Japan and the United States, each blaming the other for the tragedy. And while the rhetoric was heated between the two countries, they did agree on one thing: The problems began with the Bobbies themselves and their bad play. Dickover declared “the trip a financial failure from the start” due to a lack of competitive play by the Bobbies.38

Most records and newspaper reports show that by nearly every measure used at the time, the tour was a failure. Those measures, however, were created within the male-focused baseball sphere and included a set of standards and expectations that were very different from the ones women defined for themselves. Recognizing that fact allows for a contrasting narrative to emerge, one defined by and embraced by the women. The questions we ask about the tour, its successes and failures, are very different if we shift the perspective and therefore the narrative itself.

In the letters, diaries, and interviews produced by the Bobbies, there was no talk of failure. Instead, while honestly recording their losses and at times bad play, they also lauded their success. They spoke of freedom, adventure, and opportunity. They analyzed their own play on the field. Spangler mentioned the sharp play of Nellie Shank, the successful pitching of Edith Ruth, and the masterful play of Edith Houghton at shortstop. But in no place do they identify the tour as a failure. What accounts for the drastically different accounts of the trip? We have already seen how the creation of different baseball spheres for men and women played out in newspapers, which clearly accounts for much of the negative reporting, but that is only part of the story.

Reports of the trip by journalists, State Department officials, politicians, and Japanese promoters were written by men, using male baseball standards. For them, financial success, strengthened connections between the two governments, and winning were the necessary elements for success. On those grounds the tour was a failure. Further, these officials were primed to blame the women for that failure because women ballplayers had been depicted as either incompetent or aberrant. After all, they knew all along that women couldn’t play ball.

But when we shift the gaze and the definition of success a bit, we get a very different view of the tour, one influenced and informed from within a woman’s baseball world. Judged by standards they could never live up to in the press and elsewhere, women did not shrink away from the game. Rather, they kept playing and found measures of success that fit their baseball reality. When the Bobbies embarked on a barnstorming tour of Japan, they did so under a set of rules and expectations already in place—a prescription for success that was tried and true for male barnstormers. It is no surprise, then, that they were held responsible for its financial failure. Those writers of history, the keepers of the game, had no other standard on which to judge. But women did. For decades, they had been navigating between the boundaries of baseball’s separate spheres. And from that experience women began to develop a different way of defining, playing, and understanding baseball. Experience and opportunity were discussed alongside balls and strikes. Travel and independence influenced the game’s success as much as wins and losses. They had little say in the planning of the trip or how to proceed when things got difficult. But once it was over, their perspective, their definition of success and their thoughts on what is important about the game, made their way into the narrative of baseball history.

Nettie Spangler’s last diary entry was dated December 6, 1925.

PHILADELPHIA AT LAST! There were crowds of people at the gate when we got off the train. Of course, photographers were there to take pictures. I don’t know how we stood still; we were so excited. There were smiles and tears and I am sure every girl on the team would agree that there is no place like home. …I thanked the good lord for bringing us home safe and for the great time I had playing ball with the PHILADELPHIA BOBBIES in Japan.39

Perhaps it was naíveté or denial or simply young women experiencing the world for the first time, but whatever it was, and despite the financial hardships and the losses, the Bobbies’ trip was a complete success to the young women who completed it. That too should be part of Japanese barnstorming history.

KAT WILLIAMS is a professor of women’s sport history at Marshall University, president of the International Women’s Baseball Center, author of several articles about women’s sport including “Sport a Useful Category of Analysis,” and two books, The All-American Girls After the AAGPBL and Isabel Lefty Alvarez: The Improbable Life of a Cuban American Baseball Star. Through teaching, scholarship, and advocacy Kat is dedicated to the preservation of women’s sport history, and to helping girls become independent, confident leaders.

NOTES

1 “Chryslermen Beat Bloomer Girls, 10-8,” unknown source, Edith Houghton player file, National Baseball Hall of Fame.

2 “Chryslermen Beat Bloomer Girls, 10-8.”

3 Unknown source, Edith Houghton player file, National Baseball Hall of Fame.

4 Gordon Mackey, Unknown source, Edith Houghton player file, Hall of Fame. National Baseball Hall of Fame.

5 “Local Team Wins over Girls Nine,” unknown source, Edith Houghton player file, National Baseball Hall of Fame.

6 “Local Team Wins over Girls Nine.”

7 “Local Team Wins over Girls Nine.”

8 Despite research in the Japanese sources, Shima’s first name is unknown.

9 Barbara Gregorich, “Dropping the Pitch: Leona Kearns, Eddie Ainsmith and the Philadelphia Bobbies,” The National Pastime 43 (2013).

10 Nettie Gans Spangler Diary, Women in Baseball (WIB): Philadelphia Bobbies subject file, National Baseball Hall of Fame.

11 Spangler Diary.

12 Spangler Diary.

13 Spangler Diary.

14 Most sources estimate the attendance at 20,000 people, but some articles cited figures as high as 50,000 and 100,000. See “Girl Ball Players Returning Broke,” unknown source, Edith Houghton Hall of Fame player file; “Girl Ball Players Expect to Defeat Winsted Players,” unknown source, Edith Houghton Hall of Fame player file; “Girls’ Baseball Tour of Orient a Failure,” Lethbridge (Alberta) Herald, December 1, 1925.

15 “Bobbies Nine Defeated in Opening Game,” Times & Mail, October 24, 1925: 8.

16 “What Do the Philadelphia Bobbies Look Like?—They Look Like Good Ball Players,” Japan Times & Mail, October 20, 1920: 8.

17 “Bobbies Beaten Big Score in Final Game Here,” Japan Times & Mail, October 26, 1925: 8.

18 Spangler Diary, 2.

19 Spangler Diary, 5.

20 Spangler Diary, 6.

21 Letter from Leona Kearns to her mother, quoted in Barbara Gregorich, “Dropping the Pitch,” The National Pastime 43 (2013).

22 Letter from Leona Kearns to her mother. WIB: Philadelphia Bobbies subject file, National Baseball Hall of Fame.

23 Letter from Leona Kearns to her mother. WIB: Philadelphia Bobbies subject file, National Baseball Hall of Fame.

24 Spangler Diary, 2.

25 Letter from Leona Kearns to her mother. WIB: Philadelphia Bobbies subject file, National Baseball Hall of Fame.

26 Spangler Diary, 4.

27 “Deck Space for the Bobbies May Be the Outcome,” Japan Times & Mail, November 7, 1925: 8.

28 Spangler Diary, 8.

29 Associated Press, “Japan to Levy Tax Upon Baseball Game,” December 5, 1925, Edith Houghton Hall of Fame player file.

30 Barbara Gregorich, Research Notes for Women at Play, Volume HI. (Report from the American Consulate, Kobe, Japan, March 11, 1926), 52-53.

31 Gregorich, Research Notes for Women at Play, 51.

32 >Gregorich, Research Notes for Women at Play, 52.

33 Spangler Diary, 9.

34 Gregorich, Research Notes for Women at Play, 52

35 Gregorich, Research Notes for Women at Play, 53.

36 See “Girl Ball Players Returning Broke,” unknown source, Edith Houghton player file, National Baseball Hall of Fame; “Girl Ball Players Expect to Defeat Winsted Players,” unknown source, Edith Houghton Hall of Fame player file; “Girls’ Baseball Tour of Orient a Failure,” Lethbridge Herald, December 1, 1925.

37 Gregorich, Research Notes for Women at Play, 51.

38 Gregorich, Research Notes for Women at Play, 51.

39 Spangler Diary, 12.