Revealing a Larger Truth: A False Spring, by Pat Jordan

This article was written by Darrell Berger

This article was published in The SABR Review of Books

This article was originally published in The SABR Review of Books, Vol. 1 (1986).

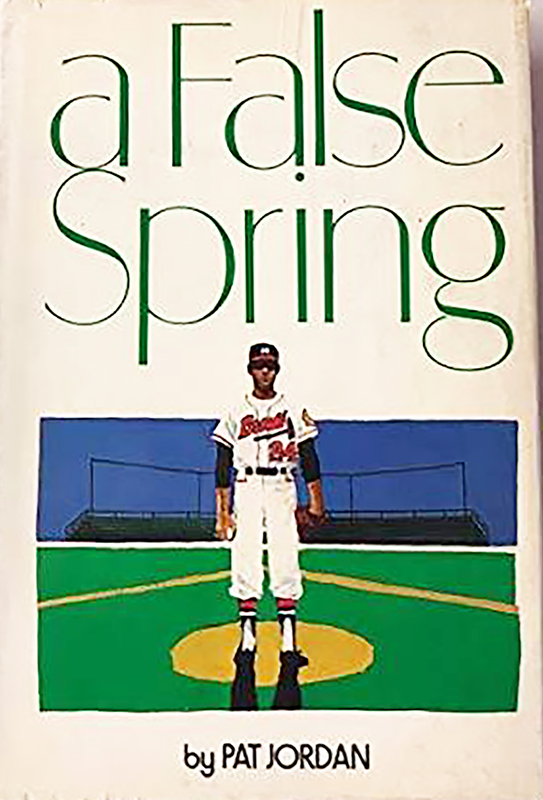

Pat Jordan pitched four consecutive no-hitters as a Little Leaguer in Fairfield, Connecticut, which earned him a trip to Yankee Stadium and an inter. view with Mel Allen. He was a Milwaukee Brave bonus bah in 1959. He had his picture taken with Warren Spahn.

Pat Jordan pitched four consecutive no-hitters as a Little Leaguer in Fairfield, Connecticut, which earned him a trip to Yankee Stadium and an inter. view with Mel Allen. He was a Milwaukee Brave bonus bah in 1959. He had his picture taken with Warren Spahn.

In three years his career was over, having never emerged from Class C. A decade later he wrote A False Spring which is not only a detailed account of the sociology of baseball at the time, but arguably the best baseball autobiography of all time. It is about failure.

Even the best books by baseball personalities, like Veeck as in Wreck and Ball Four have been co-written by professional sportswriters. Jim Brosnan’s efforts are notable exceptions. But A False Spring stands above all of them because, like The Natural, it uses baseball as a means to reveal larger truth.

We remain baseball fans, not merely for escape, but for the entry it gives us into life’s deeper meanings. Yet there is a coyness to the depth of baseball. It does not yield itself easily, just as the emotions of men together are not easily displayed.

Therefore, Jordan accomplishes a Revealing a Larger Truth By Darrell Berger rarity, a look inside the emotions of the gifted player. He was gifted; the Braves originally valued him as highly as Tony Cloninger, Phil Niekro, and Rico Carty. That his emotions are revealed through failure is what raises A False Spring from sports writing to literature.

It is the story of a young man trying to find himself, a physical young man of innocent intelligence and diffident sensitivity. As such Jordan brings to baseball what Jack Kerouac brought to hitchhiking.

A False Spring is essentially a beat generation account of baseball, even though it was written 20 years after Kerouac’s first novel was published. Its most obvious parallel is with Kerouac’s Visions of Dulouz, his autobiographical novel of the years immediately after he left Lowell, Massachusetts on a football scholarship to Columbia University. There he met Allen Ginsberg and others who were to dominate the darker comers of American literature for a generation.

Both Kerouac and Jordan were anointed by their families to take their athletic ability into the world and return with fame and fortune. Both encountered immediate opposition for the same reason: they didn’t fit in, or chose not to.

Both possessed a distant, disturbing vision. Both failed their athletic potential because their vision distracted them. Both also lacked discipline.

Here Jordan is especially candid. He writes, “Success in baseball requires the synthesis of a great many virtues, many of which have nothing to do with sheer talent. Self-discipline, single-mindedness, perseverance, ambition — these were all virtues I was positive I possessed in 1960, but which I’ve discovered over the years I did not.” This combination of arrogance and self-loathing is almost a textbook definition of “beat,” as Kerouac’s writings developed it in the 1950s.

Through this chronicle of failure we see an inverted image of what baseball success must be, and see it far better than through any book written by or about the great baseball heroes.

Kerouac and Jordan also preserve the details of their times. Kerouac described the roadside distractions of the post-war years in On the Road, Lonesome Traveler and others. Jordan details the transient life of bush league towns like McCook, Nebraska, where in 1959 a town ordinance prohibited nonwhites from living in the residential section, and Palatka, Florida, where the swamp encroached upon the games, and snakes roamed the outfield.

Both also revel in their fascination and disgust with those on the lowest rung of society, the barflies and rooming house dwellers one encounters while starting at the bottom of any enterprise. Like Zola, Dreiser and other realist novelists, Jordan describes their lives with surgical precision, occasionally uncovering genius or nobility, like minor league manager Ben Geraghty, a kind of baseball Zen master that turned boys into big leaguers.

Yet neither Jordan nor Kerouac put his talent on the line sufficiently to succeed, and both ultimately dropped out. Unfortunately for Kerouac, this meant a return to his mother’s house and the early death of a terminal alcoholic.

Fortunately for Jordan, his failure was only the failure of a game. When he dropped through the bottom of professional baseball, his life had barely begun, and A False Spring ends with intimations of that realization.

Jordan finally comprehends the reason for his failure, but far too late. His only success came in the Instructional league, after he worked with Braves’ pitching coach Whitlow Wyatt. The old curveballer gave Jordan control by altering his pitching motion, making it more compact. It was a bad bargain, for in doing so he lost the speed that made him a prospect.

He writes, “I deliberately frustrated the natural limits of my talent in the hope that this would bring me not success, even-but simply the absence of failure. Such a cowardly satisfaction! And one that ultimately led to a failure so without the satisfaction a nobler failure might have had, that I have yet to come to grips with it… to admit that I have destroyed my talent, the one thing in me that was special to me. It doesn’t matter what that thing was or how trivial it might have been. It only matters that such a thing did exist in me, as it does in us all, and that by refusing to risk perfecting it I was denying what most truly defined me.”

Or at least had defined him up to age 21. But while he was facing the awful truth that he didn’t have what it takes to be a ballplayer, another truth was unfolding. He did have what it takes to be a writer, a writer of big league caliber.

There must be an interesting story here, too, the former jock who searches for a purpose after the dream dies. He must have found a mentor, a literary Whit Wyatt to show him the quirks of mind that-failed him on the mound could support him at the typewriter.

Yet as good as A False Spring is, as good as his other writing is, Pat Jordan is not as well-known, nor probably as rich, as his talent as a writer would indicate is within his grasp.

Perhaps the personality which kept him from the top in baseball still fights success, the only difference being that writing allows for a greater range of commitment and zeal than sports, and Jordan can be what he wants to be as a writer, in a way that the all-or-nothing world of sports could never tolerate.

Jordan’s most recent work is a “Sidelines” column in the Swimsuit issue of Sports illustrated, 1986. This light, amusing and peaceful first person account tells of a graying, self-conscious 44-year-old whose wife cajoles him into riding a beach bike along the shores of Fort Lauderdale, where he now lives in a two-room, beachfront apartment.

It is writing by a man at home in his life, who undoubtedly would not be happy as a senior writer or editor of a magazine, or fighting for the top of the best seller list. That would be too much like baseball.

He is now only a few miles south of Palatka, where his baseball career drained from him. But he is his own man, in a way that being even a Hall of Famer could not have given him.

This most honest account of failure made the writer a success. Though the middle-age beach biker doesn’t mention his past, somewhere in that Fort Lauderdale apartment there must be an old photograph of a young man in a Braves’ uniform, standing next to Warren Spahn.