Revisiting the Origin of the Infield Fly Rule

This article was written by Richard Hershberger

This article was published in Fall 2018 Baseball Research Journal

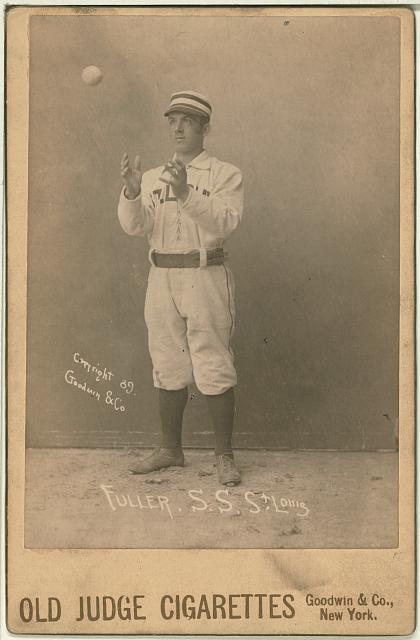

Shorty Fuller (National Baseball Hall of Fame Library)

What is a catch? A player grasps the ball. At some instant the catch is completed. If the player drops the ball before this instant, a catch has not occurred. If he drops the ball after this instant, this does not change the fact of the catch. Determining when this critical moment takes place is important in many sports.

The NFL puts the problem on weekly display. Did the receiver catch the ball before stepping out of bounds or landing on the turf? Viewers and officials study high definition slow motion footage from multiple angles, watching for any movement of the ball that might indicate something less than full control by the receiver. This exercise proves unsatisfactory for everyone. Baseball is spared this, to its great benefit. The closest thing is when a fielder fumbles the transfer from the glove to the throwing hand. In practice this is rarely a problem. The situation arises infrequently, and arouses controversy even less often.

What is a catch? Baseball was not always free of this question. Consider the following scenario: There are runners on first and second with fewer than two outs. The batter hits a fly ball to the shortstop. In the ordinary course of events, the shortstop will take the easy catch, putting the batter out. The runners, expecting this, will remain cautiously close to their bases. But suppose the shortstop instead lets the ball drop to the ground. This is now a force play, with the runners so out of position that the shortstop can pick up the ball and throw it to third base, and the third baseman can relay it to second, resulting in a double play. If the infield fly was a high pop up, the shortstop may be able to let it fall untouched in front of him and catch it on the bounce. More often, however, he will have to direct its fall. He will place his hands in position to catch the ball, but will instead of completing the catch, will drop the ball in front of himself, so that he can pick it up and make his throw to third.

This can be called the “infield fly play.” The point of the infield fly play is that the fielder can convert a double play on an easy fly ball. The problem with the infield fly play is that it allows into the Garden of Eden the question of what is a catch. The play depends on the fielder not catching the ball, while still controlling it. How long can his hands be in contact with the ball before it is a catch? How is the umpire to make this determination? How is baseball to avoid endless arguments and, in the modern era, video replays?

The solution is the infield fly rule. If the circumstances are right for the infield fly play, the batter is simply declared out, without reference to the actions of the fielder. This removes the force, and play proceeds naturally from there.

This is not the usual account of the infield fly rule. The typical explanation of its purpose focuses on the baserunner’s dilemma. The Dickson Baseball Dictionary, for example, begins the entry on the infield fly rule: “A special rule to protect the baserunners.”1 The baserunner’s dilemma is that he has, in the infield fly play, no correct course of action.

There are many plays in which the runner has no good course of action, but there is nevertheless a correct, least bad choice. Consider a runner on first with fewer than two outs, and the batter hits a routine ground ball to the shortstop. The correct play is to run hard for second base. This puts him in position to take advantage of a defensive misplay, or failing this he might be able to prevent the second baseman from turning the double play. An aggressive runner can help his team’s chances, if only slightly. The runner’s prospects are grim, but there is no dilemma.

In the infield fly play, on the other hand, the correct course of action for the runners depends on the action of the fielder, but the runners must commit before the fielder, who can be verbally assisted by his teammates about whether to catch or drop the ball. The baserunner’s dilemma is unique, and seems unfair.

Another account of the rule, complementing the baserunner’s dilemma, is the perverse incentive the infield fly play gives to the fielder. In the ordinary course of play the fielder’s goal is to catch a fly ball. (It is not quite true that this is always the case, even apart from the infield fly play. Consider a tie game in the bottom of the ninth inning with a runner on third base and fewer than two outs, when the batter hits a long fly ball that is foul but within the field of play. Catching the ball would allow the runner to tag up and score, winning the game. The outfielder should instead let the ball fall. Such situations are, however, rare.) The infield fly play gives the fielder the incentive, against all normal practice, to intentionally fail to catch the ball. This was characterized by Harold Seymour and Dorothy Seymour Mills in their seminal work Baseball: The Early Years as the defense making a double play “by subterfuge, at a time when the offense is helpless to prevent it, rather than by skill or speed.”2 This account proved attractive to the legal mind, resulting in a decades-long series of seriocomic law review articles.3

The baserunner’s dilemma and the fielder’s perverse incentive in combination provide a satisfying explanation for the infield fly rule. This can be reinforced by the observation that the rule developed in the 1890s, concurrently with the widespread adoption of fielders’ gloves. This suggests a further elaboration that the timing of the adoption of the rule was influenced by improved fielding, with gloves making easy what had been, in the barehanded days, a difficult play.

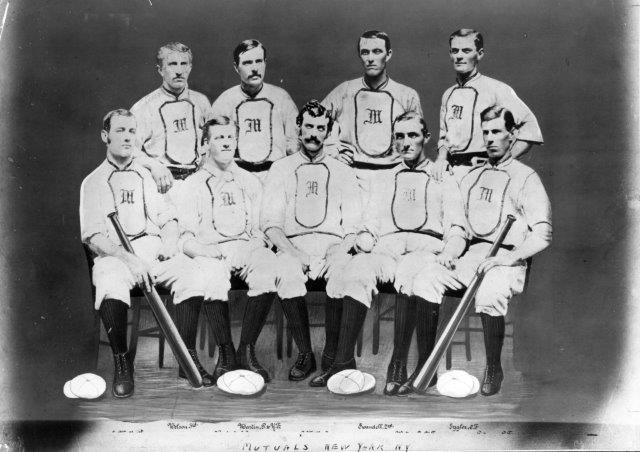

The Mutual club of New York was one of the earliest baseball clubs involved with the infield fly play. (National Baseball Hall of Fame Library)

The author long accepted this account of the infield fly rule. It is coherent and plausible. Only recently has closer examination of the antecedents to the rule shown that the actual reason for it is the problem of distinguishing what is and is not a catch. This is an extraordinary claim, and the bulk of what follows will be a defense of it. To be clear, this is a historical rather than a philosophical argument: a historical account of how and why the infield fly rule was developed; not a philosophical discussion of its implications. This does not affect the validity of discussions of the baserunner’s dilemma or the fielder’s perverse incentive, except to the extent that they claim to describe the historical development of the rule.

The infield fly play first became possible in 1859, the year the tagging up rule was instituted. The tagging up rule set up the play by forcing the runners to linger near their bases in anticipation of the ball being caught. This implication was worked out quickly. It already was an established play in 1863, as this game report makes clear:

[Atlantics v. Mutuals 8/3/1863] [Atlantics at bat, Ticknor on first base, A. Smith on third:] Start hit a high ball for [second baseman] Brown to take on the fly.… Ticknor, who runs the bases well, watched Brown closely, and running the chances of his dropping the ball and picking it up on the bound, which Brown often does to get two outs instead of one, ran for his second, and was close to it, when Brown missed the ball not only on the fly but on the bound too. Had A. Smith been quicker, he might have got home in the excitement, but in this match Smith made several errors in running his bases, thereby losing the reward of several good hits that he made.4

The problem of determining what is a catch arose soon thereafter:

[National vs. Louisville 7/17/1867] In the sixth innings a very peculiar double play was made by the Nationals, and the noise of the crowd cost the Louisvilles an out in this instance. It occurred in this way: L. Robinson was on his first when A. Robinson hit a high ball to Fox, who was playing at second.… Fox held the ball on the fly, but in turning to throw it he dropped it. The umpire called “out on the fly,” but the yells of the crowd were so deafening when Fox dropped it that L. Robinson did not hear the cry of the umpire, and seeing the ball dropped, ran for his second. Fox made no effort to pass the ball to Parker at second as he knew he had caught the ball, but leisurely passed it to Fletcher [the first baseman]. An appeal being made, the umpire called “time,” and stated to the Louisville players that he could not proceed unless better order was observed.… If a fly ball is held if but for a second or two, unless it plainly rebounds from the hand, it should be considered a catch, and when an umpires sees a ball dropped purposely for a double play, he should decide the ball dropped as a fair catch.5

It is not clear whether Fox was actually attempting the infield fly play or if the double play was merely opportunistic, but the editorial comment about what constitutes a catch clearly has the infield fly play in mind. The opinion that the ball is caught if held “but for a second or two” was not generally heeded, and the infield fly play was an established technique. Here is an example from later in the same season where the runner got caught up trying to guess what the fielder would do:

[Mutuals vs. Atlantics 8/12/1867] [Bearman at first:] McMahon then hit a high one…which was falling nicely into [second baseman] Smith’s hands, and Bearman stopped at his base; but McMahon, thinking Charley [Smith] would drop it for a double play, called to Bearman to run for second, and as Smith held the ball and then passed it to [first baseman] Start before Bearman could get back, the result was a double play, and the closing of the innings for a blank score, a round of Atlantic applause greeting the good fielding.6

The infield fly play invited controversy about whether the ball was caught:

[Cincinnatis vs. Mutuals 6/15/1869] Eggler popped up a high ball for Waterman to take, and, as it looked like a sure catch, Swandell and Mills kept their places on the second and first bases, seeing which Waterman let the ball drop from his hands, stepped on third-base, promptly sent the ball to second, and the result was that Swandell and Mills were both out, Eggler getting his base on the dropped ball.… The point played by Waterman, though apparently simple, is really one of the most difficult plays to be made in the position he occupied. In the first place, to drop a ball and avoid a catch, and yet manage to have the ball drop dead in readiness to be quickly picked up again, is very difficult to do, and Waterman failed to legally accomplish the feat. Secondly, the ball, when thus purposely missed must not be held for a second, or it becomes a catch. In this instance the ball seemed to us to have been caught—that is, it was settled in Waterman’s hands sufficiently to constitute a catch. The umpire, however, gave the field the benefit of the doubt—for there was barely a doubt—and decided both were out.7

A different reporter, discussing the same play, puts the problem in a nutshell:

There was some little uncertainty as to whether the point was properly made; whether Waterman did not actually hold the ball. Here is a nut for the expounders of the law to break their teeth on. How long must the ball be held? However, both men were declared out and the sharp play was well applauded.8

This was something of a leitmotif. No one really knew what a catch was, giving endless potential for second-guessing. The matter came to a head in 1872:

[Troy vs. Athletic 5/13/1872] [bases loaded, McBride on third:] Fisler popped one up that dropped directly into [shortstop] Force’s hands, and then out again, being purposely missed by that individual in order to make a double play. McBride, of course being under the impression that he was forced off third-base, attempted to run home, and amidst a scene of undescribable confusion, the Umpire decided that Fisler was also out, “caught on the fly” by Force, but on what rule he based that decision, we confess that we are at a loss to know, as the ball just momentarily touched Force’s hands and was not held long enough to constitute a catch. The innings closed.9

This particular game mattered because of the identity of the umpire. Umpires came and went at a furious rate in the 1870s, so questionable decisions are to be expected. Here, however, the umpire is Nicholas Young, then the secretary of the National Association and later the secretary, then president, of the National League. Young had gravitas. His opinion on what was and was not a catch commanded respect, if not necessarily agreement.

Here the umpire makes the opposite call:

[Mutual vs. Boston 5/11/1872] In the game…a precisely similar point to that of Force’s, in the Athletic-Troy, was played by Geo. Wright, but the umpire in this case made a correct decision. Hicks and McMullin were on the first and second bases, when Hatfield popped up a fly that landed into Geo. Wright’s hands and then fell out. Quickly fielding it to Schafer, Hicks was put out by being forced by McMullin, who in turn was forced out at second. This play occasioned some talk between the umpire and the captains of the rival nines, but it was allowed, of course, to pass as a muffed fly.10

The umpire here was one Moses Chandler, who umpired a total of six professional games between 1872 and 1877. The reporter’s opinion notwithstanding, Young’s opinion would prevail. The reporter did make his point in one respect: In his criticism of Young’s call he noted that Force held the ball but “momentarily.” Two years later, in 1874, this was adopted as the standard for a catch, at least in an infield fly play situation. The 1873 rule read:

Rule IV Sec. 7. In the case of a fair hit ball on the fly, the player running the bases shall not be entitled to any base touched after the ball has been hit, and before the catch has been made.

This was revised for 1874, reading:

Rule VI Sec. 11. No base shall be run, or run scored, when a fair ball has been caught, or momentarily held before touching the ground, unless the base held when the ball was hit is re-touched by the base-runner after the ball has been so caught or held by the fielder. But after the ball has been so caught or held, the base-runner shall be privileged to attempt to make a base or score a run. He shall not, however, be entitled to any base touched after the ball has been hit and before the catch is made.

The 1874 revision is mostly expanded language for clarity, making the requirements for tagging up explicit. The new part was the addition of the words “momentarily held.” This was a ratification of Young’s call two seasons previous. The reporter may have been correct that the ball had been held only momentarily, but that was all that was needed. While the language seems at face value to present two possibilities, that the fielder might either catch the ball or momentarily hold it, in reality these were two statements of the same thing. Since the runners were prohibited from running prior to the fielder catching or holding the ball, it followed that they weren’t forced off their bases, which in turn only worked if the batter were out, regardless of whether the ball were caught or merely momentarily held. The two meant the same thing.

Next, compare this with the following excerpt from the 1874 rules, which specifies how the batter is put out:

Rule V Sec. 14. The batsman shall be declared out by the umpire…if a fair ball be caught before touching the ground, no matter how held by the fielder catching it, or whether the ball first touches the person of another fielder or not, provided it be not caught by the cap.

There is no mention of the batter being out if the ball is held “momentarily.” In combination, these two rules are confusing, if not outright contradictory. Does the “momentarily held” standard apply to all situations? If so, then why is it stated only in relation to baserunners? Or are there two different definitions of a catch, depending on the presence or absence of baserunners?

The answer in practice was the latter. The “momentarily held” standard was only applied when an infield fly play situation existed. The incompatible rules were an oversight, resulting from the failure to notice that the one fix would logically affect the other rule, but this wasn’t a problem, as everyone knew what was meant.

Nicholas Young, the first secretary and future president of the National League, propounded the earliest version of the infield fly rule to avoid controversy over what was and was not a catch. (New York Public Library, A.G. Spalding Collection)

With this we have many of the elements of the modern infield fly rule. Just as with the modern rule, there is an expansion of how the batter can be put out in an infield fly situation. Just as with the modern rule, an infield fly is treated as if it were caught, even in situations where it isn’t really. And just as with the modern rule, the practical effect for the runners is usually to remain at their bases, as if the ball were caught. One difference is that the 1874 rule is not expressly limited to infield flies, but there are no known game accounts of the “momentarily held” standard being applied in this era to a fly ball to an outfielder, and it is likely that it never occurred to anyone that it would. A substantive element of the modern infield fly rule absent from the 1874 rule is that the earlier rule only applies when the fielder actually fields the ball, while the modern rule applies even if the ball reaches the ground untouched. The 1874 rule allows the infield fly double play in the case of the high pop-up that drops in front of the fielder.

The untouched fly ball will be addressed, but first we will consider why the rule was designed to treat the momentarily held ball as a catch rather than as a muffed ball. If the point is to clarify marginal catches, it would appear at first look that the rule could have gone the other direction, and defined such plays as dropped balls, and this would seem the more natural ruling. This turns out on closer examination not to solve any of the problems. As the rule was enacted, once the ball was dropped, this phase of the play was over and the umpire could declare the ball effectively caught. Had the rule declared such a ball dropped, this would have merely extended the question of how long the fielder can hold the ball before dropping it. He could catch the ball cleanly, observe that the runners had returned to their bases, then drop the ball at his leisure, reopening the force play for the easy double play. The problem would remain of ruling when the catch had truly occurred.

The overall rules were reformatted in 1880. Under the new format, the batter became a runner upon hitting the ball in fair territory. The rule for a fielder catching a fair fly ball was therefore moved to the rule on how the baserunner was put out. The “momentarily held” language was placed here, in Rule 46(1). The baserunner is out

if, having made a fair hit while Batsman, such fair hit ball be momentarily held by a Fielder, before touching the ground or any object other than a Fielder, provided it be not caught in the Fielder’s hat or cap.

The language for tagging up came in a later paragraph, in Rule 46(10). The baserunner is out

if, when a Fair or Foul Hit ball is legally caught by a Fielder before it touches the ground, such ball is legally held by a Fielder on the base occupied by the Base-Runner when such ball was struck (or the Base-Runner be touched with the ball in the hand of a Fielder), before he retouches said base after such Fair or Foul Hit Ball was so caught…

This would seem to say that the “momentarily held” standard now applied to all fair balls, and not merely in infield fly play situations. It was not understood that way. There are no game accounts, outside of infield fly situations, of batters being called out on seemingly muffed balls. The “momentarily held” standard only applied in practice to Rule 46 (10), by reference to the ball being “legally held.” This was a clumsy attempt to combine these incompatible rules in the new format. It was neither intended nor understood to be a substantive change.

This was not the only problem of rules draftsmanship. The rule simply was not well written. The “momentarily held” standard was too vague to be satisfactory. It authorized the umpire to declare the ball caught, but it provided little guidance about when he should do this. The arguments therefore continued:

Farrell purposely missed an easy catch in the fourth, when men were on first and second bases, and made a brilliant triple-play, which elicited round after round of applause.11

While the home crowd applauded the play, the Clevelands played the rest of the game under protest.12

The general response from league officials was to try to strengthen the rule. After the 1882 season, the American Association defined “momentarily held” as

making a catch of the ball if it be grasped by the fielder but for an instant. Under this ruling, therefore, a fielder desiring to make a double play must let the ball drop to the ground and catch it on the rebound close to the ground in order to effect it.13

The same year, the Spalding baseball guide included a discussion of definitions, including:

In regard to the definition of the words “momentarily held” as applicable to the catching of the ball, it should be understood that a catch is legitimately made when the fielder catching it has a fair opportunity afforded him for making the catch, and purposely fails to hold the ball after stopping it with his hands. In playing the point of refusing to accept a chance for a catch in order to make a double play, the only method officially regarded as legal is to allow the ball to fall to the ground and then to catch it on the bound, or to pick it up at once. If an easy chance is offered to make the catch, and the ball is allowed to drop from the hands of the fielder, the Umpire should regard such stopped ball as “momentarily held,” and decide the striker out on the catch.14

This was not merely journalistic opinion. Nicholas Young, in his position as National League secretary, restated the position in his official instructions to NL umpires:

The umpires’ instructions on this question are such as to defeat almost any play of the kind that can be attempted. They are required to rule that if a fielder even stops the force of the fly ball, with the object of effecting a double play, the ball shall be decided as having been caught and held. If a fielder were to put up his open hands and bounce the ball off them to the ground it would be ruled a catch, and a runner having left a base on such a play may be put out by return of the ball to the base.15

Young would repeat this instruction regularly over the ensuing years, but these exhortations were not followed consistently. Fielders continued to make the play while touching the ball. Here is an example from a game in 1885 between Chicago and St. Louis:

Pfeffer did a pretty piece of work in the ninth inning by which he recorded a double play for himself and drew forth much applause from the audience. Shafer had taken his base on Anson’s error, and had reached second on McKinnon’s base hit. Glasscock then knocked a fly to Pfeffer, which the latter dropped. Glasscock reached first, but Shafer and McKinnon, thinking that Pfeffer had held the ball, stood their bases, and Pfeffer, running to second, touched Shafer, who should have run to third, and then put out McKinnon by touching the second base with the ball.16

The state of affairs eventually reached the point that in 1893 a sportswriter responded to a report of Young’s instructions with incredulity:

President Young, in his instructions to the league umpires, in regard to the interpretation he gives to section 2 of rule 47, is evidently in error. The rule in question states that the base runner is out “if, having made a fair hit while batsman, such fair hit ball be momentarily held by a fielder before touching the ground.” Mr. Young, in his instructions to umpires interprets the words “momentarily held,” in the case of a fly ball hit to the infield and simply touched by the fielder, as a catch; while if a fly ball to the outfield be similarly touched by an outfielder it is to be scored as not a catch but an error. Most assuredly if it be a catch in the infield it must be a catch in the outfield. The cause of the forced interpretation thus give the rule is to prevent a force out play, from an intentionally dropped fly ball in the infield. But this can only be done by adding a new clause to the rule making a force out play from a dropped fly ball inoperative in the case of an infield hit and then only.… As it is now an interpretation is given the rule which applies to the infield, but not the outfield, and this the president of the league has no legal right to do.17

This brings us to the 1890 Players League. Its rules included a few changes from the existing set of the National League and American Association. One of them was a new section added to the rule on how the batter could be put out:

Rule 41 Sec. 9. The Batsman is out…if, where there is a Base Runner on the First Base and less than two players on the side at bat have been put out in the inning then being played, the Batsman make a fair hit so that the ball falls within the infield, and the ball touches any Fielder whether held by him or not before it touches the ground.

This is sometimes said to be the first Infield Fly Rule.18 In reality, it is a restatement of the 1874 rule, as interpreted by both the NL and AA. It is credited as the first because it takes a more recognizable form. Where the old inscrutable “momentarily held” language is overlooked, the PL rule says the same thing, but more clearly.

The Players League lasted just the one season. The older leagues felt no urge to borrow any ideas from it. Their rules kept the old language, retaining the old confusion. The Cleveland Leader complained about this in 1892:

The differences of opinion as to what constitutes a muffed infield fly are annoying. Each umpire is disposed to rule upon it his own way. At the next annual meeting of the League the committee upon rules should settle the matter so there will be no further mistakes.19

The National League finally addressed the problem in 1894. A new section was added to the rule on how batters are put out:

Rule 45 Sec. 9. The Batsman is out…if he hits a fly ball that can be handled by an infielder while first base is occupied with only one out.

The rule was written carelessly. It should apply only when both first and second bases (and optionally third) are occupied. (If the batter is the second out on this play, he wasn’t running very hard.) The language of “with only one out” nonsensically suggests that the rule doesn’t apply with no outs. These points were fixed over the next few years. The 1895 rules required that both first and second (and optionally third) bases be occupied for the rule to apply. Not until 1901 was the rule changed to apply “unless two hands are out.” It never made any sense to apply the rule only when there was one out. It is possible that umpires had been enforcing it that way all along.

The 1894 rule had one novelty. The rule now applied whether or not the fielder even touched the ball. Holding the ball, momentarily or longer, no longer entered into the matter. The batter was out regardless of the actions of the fielders. This, it was soon realized, allowed the umpire to call the out while the ball was still in the air. The 1897 rules codified this practice, mandating that the umpire “shall, as soon as the ball is hit, declare an infield or an outfield hit,” meaning that he inform the runners whether the batter was out or play was to continue as normal. This was changed in 1931 to the modern rule, with the umpire declaring only the infield fly, leaving an outfield fly unremarked. Several 1931 revisions brought the rules in line with actual practice. This may have been such a revision, with umpires only calling infield, and not outfield, flies all along.

The new rule removed the fielder’s actions, much less his intent, from the decision to call the batter out. The discussions behind this were held in private, so we can only speculate as to the motivation. A plausible explanation is that by rendering the actions of the fielder irrelevant, he couldn’t game the play and arguments would be avoided. The old standard, even when enforced, could still lead to arguments. Sportswriter Jacob Morse wrote in late 1893 of the proposed rule as being designed

to stop the double play on a fly ball hit to the infield whether the ball touches the infielder’s hands at all or is trapped. I have seen infielders trap the ball and yet the umpires would not allow the play. There is a great deal more disappointment on the part of the spectators when such a double play is allowed than over any other point of the play. The base runners are perfectly helpless in such emergencies. It would help run getting immensely if this change were made.20

Here, finally, we come to discussions of the base-runner’s dilemma. Several discussions around the 1894 rule included this feature. Sportswriter O.P. Caylor in 1894 offered this explanation:

This new rule was aimed particularly at McPhee of the Cincinnatis and Fred Pfeffer of the Louisvilles, who, to use the language of the boys on the sun seats, “had de play down fine as silk and made suckers outen de guys on the de bases. See?” When an infield fly went to either of those two players, men on bases were ‘twixt his satanic majesty and the fathomless ocean. If they stood still, the fly would be dropped, and they would be forced; if they ran, the fly would be caught, and so the magnates found it necessary to legislate against those two great players.21

The new, stronger form of the rule, removing entirely the infielder’s actions from consideration, may have been motivated by the baserunner’s dilemma. The idea was in the air. It came from the abolition of a play involving the dropped third strike, with its similar incentives to the infield fly play. In its original form, the dropped third strike rule applied regardless of the situation. So, for example, with the bases loaded and fewer than two outs, the catcher could intentionally drop the third strike, pick up the ball, tag home plate for the force out, and throw the ball to first base for the second out. The two plays presented similar difficulties for the umpire, and the same standard of “momentarily held” was applied. The dropped third strike presented the additional challenge that the single umpire positioned behind the catcher was peculiarly ill-positioned to see whether the catcher held the ball, even momentarily.22 For this reason, the rule was changed for 1887 to the modern form, where the dropped third strike rule does not apply if first base is occupied with fewer than two outs. The Detroit Free Press, for one, approved of the change:

Heretofore the rule declaring a batter out “if the ball be momentarily held,” has led to a vast amount of wrangling among opposing players, dissatisfaction to spectators, and yowling at the umpire. This new rule is intended to put a stop to all this disgusting confusion. When there is a man on first and no more than one man out…what has been the point of sharp play by the catcher? To purposely muff the third strike, force both men to run, and then, by throwing to second, to make a double play. This he can no longer do, the batter being out upon the fourth missed strike [four strikes being required for an out in 1887], no matter whether the ball is caught or not.23

The dropped third strike play presented a baserunner’s dilemma similar to that of the infield fly play, where a runner would find himself forced off his base in a situation where ordinarily the correct play would be to stay in place. This wasn’t why the dropped third strike rule was changed, but an urban legend arose that it had been. This in turn gave rise to the idea that the infield fly rule served the same purpose. In 1893 Washington manager Gus Schmelz tied the two together:

No double playing should be allowed on a trapped ball when there is more than one man on a base. If the play can be made when first base alone is occupied, through the carelessness of the batsman in not running out his hit, all well and good, but in every other case where a double is possible the batsman should be given out when the ball is hit up over the infield. The catcher was stopped from making a double by dropping the third strike when first base was occupied, because it made a monkey out of the base runner. The trapped ball should go for the same reason.24

With the 1894 infield fly rule, the “momentarily held” language was now obsolete, but in a characteristically sloppy piece of legal draftsmanship, it remained on the books. Its purpose was soon forgotten. The rule was rarely cited, and even more rarely under happy circumstances. This report of a Pirates-Giants game in 1914 is one example:

When is a ball “momentarily held,” is a question which Umpire Mal Eason decides one way, and Umpire Bill Klem another. In Wednesday’s game at the Polo Grounds, Mike Mowrey hit a line drive to left field which Burns got under at the fence, juggled the ball, collided with the stand and then dropped the ball.

“You are out!” yelled Eason to Mowrey, who had rounded second. “He dropped that ball,” came back Mowrey. “He momentarily held it,” said Eason with the entire Pirate squad surrounding him.

In yesterday’s game at Brooklyn, Eddie Collins, in the eighth inning, after a hard run, caught a fly hit by Cutshaw. The youngster couldn’t stop and after carrying the ball fully five yards it dropped out of his hands. Klem declared Cutshaw, who reached second, safe, and when Clarke and Wagner insisted Collins had momentarily held the ball, Klem waved them away and declared, “There ain’t no such thing.”25

Here Thomas Holmes of the Brooklyn Eagle, writing in 1928, takes a cynical view of the rule, that it served mainly to let umpires justify blown calls:

There is something in the rules saying that a thrown or batted ball to be caught must be “momentarily held,” and apart from providing umpires with an easy alibi, it doesn’t mean a thing. This rule gives a mistaken umpire a great break. If he calls one too soon or calls one obviously wrong, he can sometimes get out of the jam with honor intact by saying: “Well, the ball was momentarily held, wasn’t it?” and who can say him nay? For any ball that hits in the pocket of a player’s glove is momentarily held.

The interpretation of this vague and unnecessary phrase narrows down to a question of how long is a moment. The answer of that is largely a matter of what the umpire had for lunch and whether it agreed with him.26

Not until 1931 was the “momentarily held” language finally cleansed from the rules.

The infield fly rule is occasionally criticized today, usually in two forms. The first is to criticize borderline (or perceived borderline) infield fly calls and suggest that these could be avoided by doing away with the rule. The prominent recent example is the 2012 NL wild-card game between the Cardinals and the Braves. With runners at first and second and one out—the classic infield fly situation—Braves batter Andrelton Simmons popped a ball into shallow left field. Cardinals shortstop Pete Kozma was in position to catch the ball, then moved away, apparently to cede the play to left fielder Matt Holliday. The ball dropped. This initially seemed to result in the bases being loaded, but umpire Sam Holbrook had called an infield fly. The result was runners on second and third—having advanced as with any uncaught fair ball—with two outs. Regardless of the correctness of the call itself, the play shows the intrinsic problem of the borderline infield fly. In practice, however, this occurs very rarely. The 2012 game resulted in a flurry of debate, which rapidly disappeared.27

The second critique is more substantial: The infield fly rule rewards failure. Where the baserunner’s dilemma looks at the play from the baserunner’s perspective, and the fielder’s perverse incentive to drop the ball looks at it from the fielder’s, this critique looks at the play from the point of view of the batter. Whatever he was trying to achieve, an infield fly was not it. So why is he protected from a double play? A sharp ground ball to the shortstop or a line drive at the first baseman would most likely have resulted in a double play and no one would suggest that this was anything less than fair. So why should an infield fly be any different? The response to the baserunner’s dilemma and the fielder’s perverse incentive in this critique is “So what?” It has a point.

What is a catch? This question rebuts the critiques. Imagine watching ultra-slow-motion replay from various angles: Did the shortstop’s glove close around the ball just enough that the ball was caught? Did the ball move around in the glove enough that it was never secured? This would, absent the infield fly rule, be the world we lived in. It’s a world no one wants.

RICHARD HERSHBERGER writes on early baseball history. He has published in various SABR publications, and in “Base Ball: A Journal of the Early Game.” He is a paralegal in Maryland.

Notes

1. Paul Dickson, The Dickson Baseball Dictionary, 3rd ed. (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2009), 451.

2. Harold Seymour and Dorothy Seymour Mills, Baseball: The Early Years (New York: Oxford University Press, 1960), 276.

3. The first was “Aside: The Common Law Origins of the Infield Fly Rule.” 1975. University of Pennsylvania Law Review 123 (6): 1474. The unsigned article was by William S. Stevens, then a student at the University of Pennsylvania Law School. Recent examinations of the idea, and riffs on Stevens’s article, include Andrew J. Guilford & Joel Mallord, “A Step Aside: Time to Drop the Infield Fly Rule and End a Common Law Anomaly.” 2015. University of Pennsylvania Law Review 164 (1): 281; and Howard M. Wasserman, “Just a Bit Aside: Perverse Incentives, Cost-Benefit Imbalances, and the Infield Fly Rule.” 2016. University of Pennsylvania Law Review 164 (1): 145.

4. “Sports and Pastimes,” New York Sunday Mercury, August 9, 1863.

5. “The Nationals at Louisville,” Ball Players Chronicle, July 25, 1867.

6. “Grand Club Match in Brooklyn,” Ball Players Chronicle, August 15, 1867.

7. “Sports and Pastimes,” New York Sunday Mercury, June 20, 1869.

8. “The National Game,” New York Herald, June 16, 1869.

9. “Base Ball,” Evening City Item (Philadelphia), May 14, 1872. This account is unclear about the third out, but another account of the same game states that Force relayed the ball to the third baseman, intending for a force play on the runner from second but credited per Umpire Young’s decision as putting out the runner from third, who failed to tag up. “Athletic vs. Troy,” Philadelphia Sunday Mercury, May 19, 1872.

10. “Base Ball,” Evening City Item (Philadelphia), May 16, 1872.

11. “Providence vs. Cleveland,” New York Clipper, August 14, 1880.

12. “In and Out-Door Sports,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, August 6, 1880.

13. “Good Boys,” Cincinnati Enquirer, December 14, 1882.

14. Spalding’s Base Ball Guide: Official League Book for 1883 (Chicago: A.G. Spalding & Bros., 1883), 28-29. The same language is in the 1884 edition, but the entire section omitted thereafter.

15. “Instructions of League Umpires,” Sporting Life, June 3, 1883.

16. “Sporting Matters,” Chicago Tribune, June 10, 1885.

17. “Praying Hard for Rain,” Brooklyn Eagle, May 17, 1893.

18. Peter Morris, A Game of Inches, 2nd ed. (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee 2010), 164.

19. “March On, March On,” Cleveland Leader, August 18, 1892.

20. Jacob C. Morse, “Hub Happenings,” Sporting Life, November 4, 1893.

21. O.P. Caylor, “The Baseball Outlook,” Daily Illinois State Journal, March 11, 1894.

22. For a longer discussion of the history of the dropped third strike rule, see Richard Hershberger, “The Dropped Third Strike: The Life and Times of a Rule,” Baseball Research Journal, vol. 44, no. 1, Spring 2015.

23. “Ciphers for Memphis,” Detroit Free Press, April 10, 1887.

24. “Schmelz’s Idea,” Sporting Life, November 4, 1893.

25. “Conferences of Pittsburg Club Officials May Mean More Pirate Deals,” Pittsburgh Press, August 1, 1914.

26. Thomas Holmes, “Umpires Make a Joke out of the Old ‘Momentarily Held’ Rule,” Brooklyn Eagle, July 13, 1928.

27. The call clearly was correct. The fielders were not attempting to turn a double play, and the ball dropping uncaught was inadvertent. Intent is not, however, a consideration in the rule. The ball could have been caught by an infielder with ordinary effort. That the fielder did not make that ordinary effort is irrelevant, and that he would not was unknowable to the umpire when he had to make the call. More abstractly, were there no infield fly rule, the shortstop could have turned an infield fly double play on that ball.