Rickwood Field Adds to Its Legacy as the Major Leagues Return to Alabama

This article was written by Kevin Warneke - John Shorey

This article was published in Spring 2024 Baseball Research Journal

The oldest professional baseball park in the United States—Rickwood Field in Birmingham, Alabama—adds another chapter to its rich history this summer when it hosts the San Francisco Giants and St. Louis Cardinals in a regular-season game.1 The specialty game will coincide with Juneteenth celebrations and honor Hall of Famer Willie Mays, who played for the Birmingham Black Barons at Rickwood Field in 1948.2

The Giants-Cardinals contest will be the first American or National League game held at Rickwood Field as well as the first in Alabama.3

MLB RECOGNIZES THE NEGRO LEAGUES

In December 2020, Commissioner Rob Manfred announced that Major League Baseball was correcting “a longtime oversight” in the game’s history by officially recognizing that the Negro Leagues were deserving of the designation “major”—joining the Federal League, American Association, and several other defunct leagues that share that status.4 The announcement said that MLB was proud to showcase the contributions of those who played in seven distinct leagues from 1920 through 1948. “With this action, MLB seeks to ensure that future generations will remember the approximately 3,400 players of the Negro Leagues during this time period as Major League–caliber ballplayers. Accordingly, the statistics and records of these players will become a part of Major League Baseball’s history.”5

“I’ve always recognized Negro League players as major-league quality,” Larry Lester, a co-founder of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City, said. “I didn’t need an official governing body to tell me that. I’m happy they did. They finally recognized that Black men played the game also.”6

IMPACT ON OTHER STATES

Alabama is one of four states that had their connection to the major leagues altered with MLB’s announcement. In the past decade, MLB has scheduled regular-season games in North Carolina, Nebraska, and Iowa—all of which had hosted regular-season Negro League games:

NORTH CAROLINA – Called the “Fort Bragg Game,” the July 3, 2016, contest between the Atlanta Braves and the Miami Marlins was the first regular-season event of any professional sport played on an active military base.7 The game was also labeled a major-league first for the state of North Carolina—and held that distinction until MLB’s announcement recognizing the Negro Leagues.8 Now, a May 25, 1948, game between the Homestead Grays and the Philadelphia Stars at Talbert Park in Rocky Mount holds the distinction of being the first standings-relevant major-league game played in the state. Lefty Bell went nine innings for the Grays in Homestead’s 9–3 victory over the Stars, both members of the Negro National League. Wilmer Fields collected four runs batted in for the winners.9

NEBRASKA – The Kansas City Royals’ 7–3 victory over the Detroit Tigers in June 2019 before a sellout crowd of 25,454 at Omaha’s TD Ameritrade Park was called Nebraska’s first major-league game. Eighteen months later, after MLB’s announcement, that distinction changed to a Kansas City Monarchs-Chicago American Giants game at Landis Field in Lincoln on July 27, 1939. Nearly 1,000 fans saw the Monarchs win, 3–2, by scoring two runs on a bad-hop, bases-loaded single in the bottom of the ninth.10

IOWA – Manfred’s announcement that MLB was recognizing the Negro Leagues as major leagues came between the announcement of a regular-season game on the site where Field of Dreams had been filmed and that game’s first pitch.11 The August 12, 2021, matchup pitted the New York Yankees against the Chicago White Sox, two historic franchises, with the White Sox featured in the film. John Thorn, MLB’s official historian, pointed out that Iowa had a rich major-league history long before the Yankees and White Sox came to town.12 Although no teams recognized as major league by MLB had franchises in Iowa, barnstorming was a major component of Negro League operations. At least 30 games between Negro League teams that counted in the standings were played in the Iowa communities of Charles City, Council Bluffs, Davenport, Des Moines, and Sioux City from 1937 to 1948. The first was apparently in Des Moines on May 27, 1937—following three previous attempts that were rained out—between the Cincinnati Tigers and the Birmingham Black Barons. Birmingham used a five-run outburst in the top of the fifth to go ahead in its 8–4 win.13

FIRST MAJOR LEAGUE GAME AT RICKWOOD FIELD

The specialty game this summer will not only celebrate the Negro Leagues and Willie Mays, it will commemorate the 100th anniversary of the debut of major-league baseball at Rickwood Field. Black Barons pitcher Bill Powell said playing at Rickwood was special: “I don’t know what it is, but when I was playing at Rickwood Field, I was always itching to get to the ballpark. We played all over the United States, and when we got here, you just loved coming here to play in this park. There was just something about the baseball in that park.”14

The change in status for the Negro Leagues means that a game played 100 years ago at Rickwood between the Black Barons and the Cuban Stars has moved to the front of the line as the first major-league game played at the historic ballpark—and in the state of Alabama.

While North Carolina, Nebraska, and Iowa never had Negro League franchises that called their states home, Alabama had two Negro League franchises that are now recognized as major league: the Birmingham Black Barons and the Montgomery Grey Sox.15 The Black Barons benefitted by playing their home games at Rickwood, the crown jewel of southern baseball. Built in 1910 for the Barons, a Class A Southern Association team comprising white players, by their owner, A.H. “Rick” Woodward, the venue also hosted Negro League contests.16 The ballpark name, combining the nickname and part of the last name of the owner, was suggested by a fan in a newspaper contest.17

With the growing popularity of Black baseball in Birmingham, Woodward saw an economic opportunity and rented out his ballpark to Black teams for a percentage of the gross ticket sales.18 A 1919 Labor Day doubleheader at Rickwood between Black teams from Birmingham and Montgomery drew 15,000 spectators. The Birmingham Age-Herald reported that the doubleheader saw “the largest crowd of Negroes that ever attended a ball game in the United States and next to the largest, irrespective of color, that ever jammed into Rickwood.”19

The same year that Rube Foster organized the Negro National League in 1920 (the earliest Negro League to be recognized as major league), the Birmingham Black Barons were formed. The team’s original nickname, Stars, was quickly changed to Black Barons, a reference to the white team in Birmingham. The Black Barons were a founding member of the Negro Southern League. In 1923, Birmingham hotel owner Joe Rush purchased the team and joined the Negro National League as an associate member, meaning the Black Barons were affiliated with the league but their games didn’t count in the standings.20 The transition to the new league came in July after the Black Barons dominated the Negro Southern League with a 24–8 record in the first half of the 1923 season.21

The move by the Black Barons to the Negro National League was touted by the Birmingham News as the first baseball team from Birmingham to have membership in a major-league association.22 A large interracial crowd attended the first home game in the new league on July 19, 1923, against the Milwaukee Bears.23 The Bears jumped out to an early 2–0 lead and had the locals wondering whether the Black Barons were out of their class. The Black Barons battled back and pulled ahead, 4–3, with two tallies in the bottom of the eighth inning. Milwaukee pushed across a run in the top of the ninth to knot the score at 4–4. After a scoreless 10th inning, the contest was halted due to darkness.24

Birmingham ended the 1923 season as an associate member of the Negro National League with a record of 15–23.25 When the Chicago American Giants, the premier team of the Negro National League, traveled to Birmingham later in the season to take on the Black Barons, the Chicago Defender commented: “For the first time in the history of the Negro National League the American Giants of Chicago will leave home during the middle of the season and make a trip South, playing in Birmingham on Aug. 20, 21 and 22. These three days will be gala days in the Southern metropolis and many people are expected to come out and witness the new Southern entry into the Negro National League play Rube Foster’s club, thrice winners of the league pennant.”26

The first official major-league baseball game in the state of Alabama took place the following year on April 28, 1924, at Rickwood Field after the Birmingham Black Barons became full members of the Negro National League. A crowd of 10,600, the second largest to ever see a Negro League game at Rickwood Field at that time, poured into the ballpark to witness the successful debut of the Black Barons. The Cuban Stars pushed across a pair of runs in the top of the third on three singles and a throwing error to take a short-lived lead. The Black Barons answered back immediately in the bottom of the frame with a five-run outburst on five singles and a dropped fly ball. Both teams scored an additional run to make the final 6–3, Black Barons.27

NOTABLE BIRMINGHAM BLACK BARONS PLAYERS

The Birmingham Black Barons fielded a team on and off in various Negro Leagues for 33 seasons. They won five Negro American League titles in the 1940s and 1950s.28 During their seasons that are now recognized as major league, the Black Barons’ rosters included four Hall of Famers.

Midway through the 1927 season, the Black Barons purchased a young, hard-throwing pitcher from the Chattanooga Black Lookouts named Leroy “Satchel” Paige.29 Paige won his first major-league game while posting a 7–2 record for the Black Barons in his rookie season.30 His first big game with his new team in late June was notable for a hit-and-run, but not the sort common to baseball lingo. When a Paige heater smacked St. Louis Stars catcher Mitchell Murray on the hand, Murray charged the mound waving his bat. Paige outran Murray to the dugout, but not the bat. The bat struck Paige above the hip. A near riot ensued, with players massing from both benches along with knife- and rock-wielding fans. After police restored order, the umpire tried to resume play after ejecting Paige and Murray. The Black Barons refused to take the field without their pitcher, thus forfeiting the game.31

In 1929, his third season with the Black Barons, Paige struck out a record 17 Detroit Stars batters in a 5–1 win on July 29.32 He ended his tenure with the Black Barons when he was sold to the Nashville Elite Giants in 1931.33

Another Hall of Famer who made his major-league debut with the Black Barons was George “Mule” Suttles. Early in his career, the power-hitting first baseman’s home run total was hampered by the dimensions of his home park at Rickwood: 411 feet to the left-field fence and 485 feet to the center-field wall.34 (The outfield dimensions at Rickwood Field have periodically changed over the years.) The long distances to left and center fields were inspired by Shibe Park, home of Connie Mack’s Philadelphia A’s. After meeting Woodward shortly after the opening of Shibe Park in 1909, Mack agreed to come to Birmingham to help design the new ballpark.35

After two major league seasons with the Black Barons, Suttles blossomed into a star with the St. Louis Stars during the 1926 season. In just 89 games that season, Suttles produced 32 home runs, 28 doubles, 19 triples, 15 stolen bases, and 130 RBIs. He ended the season with a .425 batting average.36

Rube Foster’s brother Bill, who was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1996, appeared in just one game for the Black Barons in 1925, pitching a one-hit complete game shutout before returning to his original team, the Chicago American Giants.37 Foster was a hard-throwing lefty with pinpoint control and a great changeup. On the last day of the 1926 season, he won both ends of a crucial doubleheader to clinch the pennant for the American Giants.38

In the final year that the Black Barons are recognized as major-league caliber, 1948, a 17-year-old center fielder collected two hits in the second game of a doubleheader.39 Those were the first two of 3,293 hits for Willie Mays during his Hall of Fame career.40 His two hits came off of Cleveland Buckeyes’ hurler Chet Brewer, who had broken into the league with the Kansas City Monarchs in 1925, six years before Mays was born.41

The Black Barons featured other notable players besides their four Hall of Famers. Ted “Double Duty” Radcliffe played for the Black Barons in the mid-1940s as a catcher and a pitcher, hence the moniker “Double Duty.” During a 1932 Negro World Series doubleheader early in Radcliffe’s career, he caught Paige in the first game and then pitched a shutout in the second game.42

Reece “Goose” Tatum played two seasons for the Black Barons in the early 1940s, earning his first major-league hit in the summer of 1941. While Tatum’s major-league baseball career was short-lived, he went on to become the main attraction of the Harlem Globetrotters basketball team.43 Tatum’s connection between baseball and basketball was facilitated by a new part owner of the Birmingham Black Barons, Abe Saperstein, who founded the Globetrotters.44

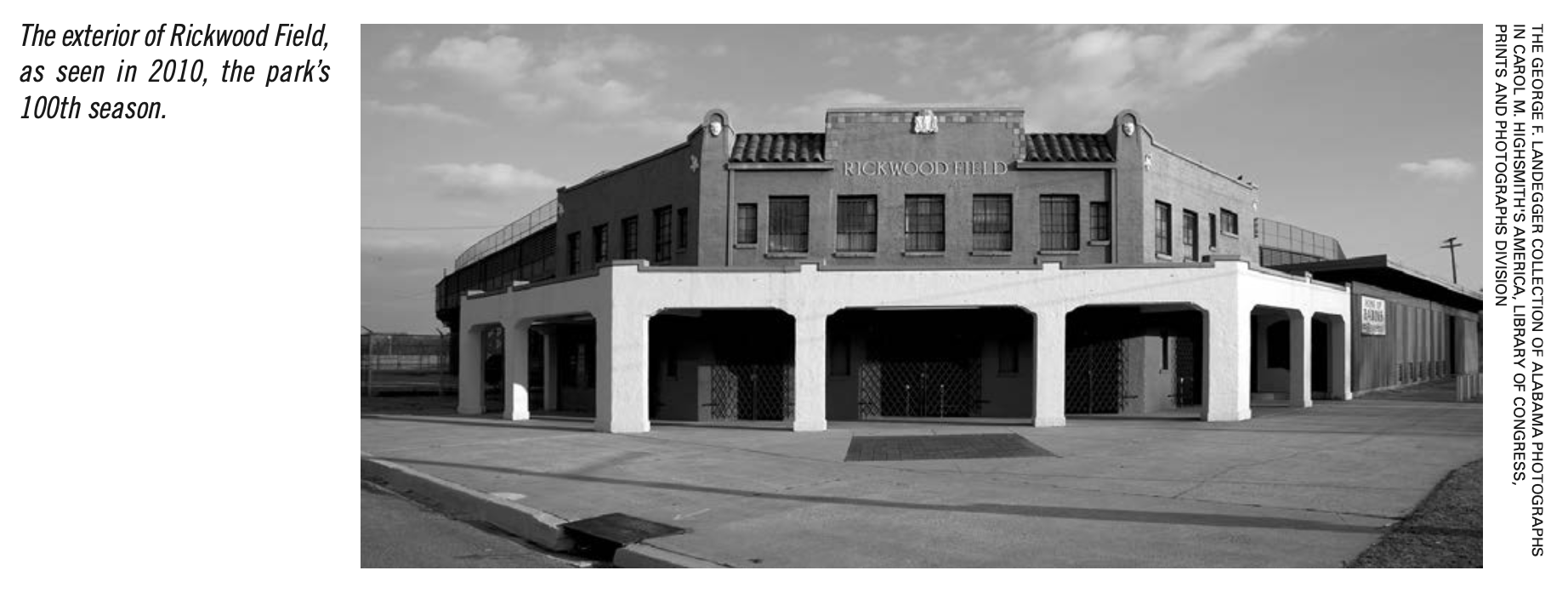

RICKWOOD FIELD

Rick Woodward was determined to enhance his jewel of Southern baseball, which had been built in 1910 at a cost of $75,000.45 Starting in 1924, he extended the grandstand roofs in phases down the right- and left-field bleachers to protect the fans from the brutal Alabama summer sun. A 40-foot-high scoreboard was erected in left-center, and the iconic Spanish mission–style façade with twin parapets was added to Rickwood’s front gate in 1928.46 The unique steel-frame light towers, which reach out past the grandstand roof, were added in 1936.47

Rickwood Field also became the home ballpark of an affiliated minor-league team in the 1930s as the Birmingham Barons became the farm team of various major-league teams—the Cubs, Reds, Pirates, A’s, Red Sox, Yankees, Tigers, and, since 1986, the White Sox.48

The Black Barons joined the Negro American League in 1937. They enjoyed their greatest success in the 1940s, winning three Negro American League championships.49

The integration of major league baseball by Jackie Robinson in 1947 signaled the gradual decline of the Negro Leagues. Toward the end of their existence, the Black Barons became more of a traveling team and finally folded after the 1962 season.50

Rickwood Field continued to be the home park for a Double A affiliate of major-league teams through the 1987 season. The White Sox moved the Birmingham Barons to a new ballpark in Hoover, Alabama, a suburb of Birmingham, in 1988.51

In order to preserve the legendary ballpark, a group of Birmingham fans, businesses, and civic leaders formed the “Friends of Rickwood” in 1992. Over the next decade more than $2 million was spent maintaining and restoring Rickwood Field.52 The following year, the National Parks Service’s Historic American Building Survey officially recognized Rickwood Field as the oldest professional baseball park in the United States.53

Due to the preservation efforts over the past several decades, Rickwood Field has continued to thrive. The Rickwood Classic is an annual event in which the Birmingham Barons play one regular-season game at the old ballpark while wearing throwback Negro League uniforms. A full slate of high school games and wood-bat tournaments are held there each year.54 It is also the home field for Miles College, a historically black college in suburban Fairfield, and has served as a location for baseball films such as Cobb (1994), Soul of the Game (1996), and 42 (2013).55

JOHN SHOREY is a history professor emeritus from Iowa Western Community College, where he taught an elective course on Baseball and American Culture for 20 years. He has written articles and chapters on a variety of baseball topics for various publications and is a regular contributor to Baseball Digest. He has presented his research at the Cooperstown Symposium on Baseball and American Culture along with other baseball conferences.

KEVIN WARNEKE, who earned his doctoral degree from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, is a fundraiser based in Omaha, Nebraska. He co-wrote The Call to the Hall, which tells the story of when baseball’s highest honor came to 31 legends of the game.

Notes

1 “Rickwood Field to host MLB, MiLB games in 2024,” MiLB.com, June 20, 2023, https://www.milb.com/news/rickwood-field-to-host-mlb-milb-games, accessed November 19, 2023.

2 “Rickwood Field to host MLB.”

3 Bob Nightengale, “MLB to play 2024 regular season game at Birmingham’s historic Rickwood Field,” USA Today, June 20, 2023, https://www.usatoday.com/story/sports/mlb/2023/06/20/birminghams-rickwoodhistoric-rickwood-field-to-host-mlb-game-in-june-2024/70336931007/, accessed November 19, 2023; Patrick Andres, “Giants, Cardinals to Play 2024 Game at Birmingham’s Historic Rickwood Field,” Sports Illustrated, June 20, 2023, https://www.si.com/mlb/2023/06/20/giants-cardinals-to-play-in-birmingham-2024-rickwood-field-willie-mays-juneteenth, accessed November 19, 2023.

4 A note on the confusing capitalization: Major League Baseball, when capitalized, identifies the current corporate entity that is made up of the 30 teams in the American and National Leagues. The major leagues, lowercase, is a descriptor of baseball’s top level of play, which Major League Baseball announced in 2020 included the Negro Leagues. Note also that MLB, in its press releases, capitalizes major league in all uses.

5 “MLB officially designates the Negro Leagues as ‘Major League,’” MLB.com, December 16, 2020, https://www.mlb.com/press-release/press-release-mlb-officially-designates-the-negro-leagues-as-major-league

6 Kevin Warneke and John Shorey, “This small Nebraska town hosted Negro League clubs and possibly a Major League game,” Flatwater Free Press, March 31, 2023, https://flatwaterfreepress.org/this-small-nebraska-town-hosted-negro-league-clubs-and-possibly-an-official-major-league-baseball-game/

7 John Schlegel, “Stars and Spikes: July 3 game at Fort Bragg!” March 8, 2016, MLB.com, https://www.mlb.com/news/braves-marlins-play-fort-bragg-game-on-july-3-c166636990, accessed October 30, 2023.

8 Arthur Weinstein, “Braves, Marlins make history in game at Fort Bragg military base,” Sporting News, July 3, 2016, https://www.sportingnews.com/us/mlb/news/braves-marlins-fort-bragg-field-mlb/d9yjuy7bczvq1wkgxli0a615g, accessed November 19, 2023.

9 “Homestead Grays (HOM) 9 Philadelphia Stars (PH5) 3,” Retrosheet, https://www.retrosheet.org/NegroLeagues/boxesetc/1948/ B05250HOM1948.htm, accessed February 6, 2024.

10 Warneke and Shorey, Flatwater Free Press.

11 John Shorey and Kevin Warneke, “Major League Baseball in Iowa,” The National Pastime 51 (2023), 63.

12 John Thorn tweet, August 21, 2021, https://twitter.com/thorn_john/status/1425441694481330179

13 Shorey and Warneke, 64.

14 Allen Barra, Rickwood Field: A Century in America’s Oldest Ballpark (New York: Norton, 2010), ix.

15 The Montgomery Grey Sox achieved major-league status for one season when MLB designated the Negro Southern League as major-league caliber for the 1932 season.

16 Barra, 21–22.

17 Barra, 24.

18 Barra, 58.

19 Barra, 58.

20 Larry Powell, Black Barons of Birmingham (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2009), 10.

21 “Negro Southern League (1920–1951),” Center for Negro League Baseball Research, https://www.cnlbr.org/Portals/0/Standings/Negro%20Southern%20League%20%20(1920–1951)-2020.pdf, accessed November 20, 2023.

22 “Black Barons Play First Game As Big Leaguers Thursday,” Birmingham News, July 17, 1923, 26.

23 The Birmingham News story incorrectly identified the Milwaukee team as the Giants. The correct moniker for Milwaukee in 1923 was the Bears.

24 “Black Barons Tie First Big League Game,” Birmingham News, July 20, 1923, 18.

25 “Negro National League Standings (1920-1948),” Center for Negro League Baseball Research, https://www.cnlbr.org/Portals/0/Standings/Negro%20National%20League%20(1920-1948)%202016-08.pdf, accessed November 20, 2023.

26 “Black Barons Face Hard Week’s Work,” Birmingham News, July 29, 1923, 34.

27 “Record Crowd Sees Rushmen Annex Opener,” Birmingham News, April 29, 1924, 16.

28 “Birmingham Black Barons,” the Negro Leagues, https://www.mlb.com/history/negro-leagues/teams/birmingham-black-barons, accessed November 20, 2023.

29 Powell, Black Barons of Birmingham, 19.

30 “Satchel Paige,” Baseball Reference, https://www.baseball-reference.com/players/p/paigesa01.shtml, accessed November 20, 2023.

31 Larry Tye, Satchel: The Life and Times of an American Legend (New York: Random House, 2009), 43.

32 Powell, 20.

33 Robert Peterson, Only the Ball Was White (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1992), 133.

34 Powell, 29.

35 Barra, Rickwood Field, 2–4.

36 “Mule Suttles,” Baseball Reference, https://www.baseball-reference.com/players/s/suttlmu99.shtml, accessed November 20, 2023.

37 “Bill Foster,” Baseball Reference, https://www.baseball-reference.com/players/f/fostebi99.shtml, accessed November 20, 2023.

38 National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum 2022 Yearbook (Lynn, MA: H.O. Zimman, 2022), 75.

39 James S. Hirsch, Willie Mays: The Life, The Legend (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2010), 43.

40 “Willie Mays,” Baseball Reference, https://www.baseball-reference.com/players/m/mayswi01.shtml, accessed November 20, 2023.

41 Hirsch, 42–43.

42 Powell, 48.

43 Powell, 50.

44 Mark Ribowsky, A Complete History of the Negro Leagues, 1884 to 1955 (New York: Carol Publishing Group, 1995), 248.

45 Hirsch, 41.

46 Barra, 75–79.

47 Barra, 117.

48 “Birmingham Barons,” Baseball Reference, https://www.baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Birmingham_Barons, accessed December 18, 2023.

49 “Negro American League Standings (1937–1962),” Center for Negro League Baseball Research, https://www.cnlbr.org/Portals/0/Standings/Negro%20American%20League%20(1937-1962)%202016-08.pdf, accessed December 18, 2023.

50 “Negro American League Standings (1937–1962).”

51 Barra, 201.

52 Barra, 205.

53 Barra, 211.

54 Bruce Markusen, “Rickwood Field features baseball’s past and present,” National Baseball Hall of Fame, https://baseballhall.org/discover/rickwood-field-features-baseballs-past-and-present, accessed December 18, 2023.

55 “Field of Dreams Game 2024,” FieldOfDreamsGameTickets, https://www.fieldofdreamsgametickets.com, accessed December 18, 2023.