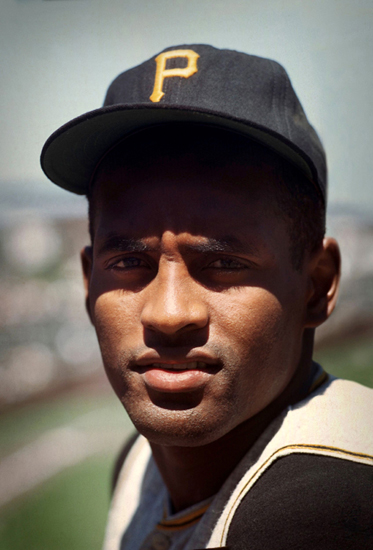

Roberto Clemente and the Big Grab

This article was written by Benjamin Sabin

This article was published in ¡Arriba! The Heroic Life of Roberto Clemente (2022)

This story begins and ends with fried chicken. It also includes four armed men, an All-Star ring, an abduction, and a brush with the grim reaper. Oh yeah, and in the middle of it is the greatest Puerto Rican baseball player of all time, Roberto Clemente. So why isn’t this story common knowledge among baseball fans? How do we not know the story’s specifics like we know that Clemente has exactly 3,000 hits or that he has a lifetime .317 batting average? Because nobody is sure if the following events even took place. That’s right, we have a mystery on our hands.

This story begins and ends with fried chicken. It also includes four armed men, an All-Star ring, an abduction, and a brush with the grim reaper. Oh yeah, and in the middle of it is the greatest Puerto Rican baseball player of all time, Roberto Clemente. So why isn’t this story common knowledge among baseball fans? How do we not know the story’s specifics like we know that Clemente has exactly 3,000 hits or that he has a lifetime .317 batting average? Because nobody is sure if the following events even took place. That’s right, we have a mystery on our hands.

THE BIG GRAB

Time has a way of blurring the details. What one remembers about an incident the day after the occurrence may be very different from what they recall, say, a year later. And such may be the case with Roberto Clemente’s alleged kidnapping that took place in 1969 but wasn’t made public until Clemente sat down with Pittsburgh Press reporter Bill Christine on August 9, 1970. Also, the only account we have to go on is Clemente’s, so there is no one to corroborate or disprove his account.

We know that the supposed abduction took place in San Diego in 1969. The Pirates visited San Diego twice that season. The first three-game series took place May 20 to 22 at San Diego Stadium. Published reports list this series as the time of the incident. The second series the Pirates played in San Diego, from August 8 to 10, better matches certain details given by Clemente, except, of course, the date that he stated as the time of the incident.

So what is the story? It goes like this: It was a dark and stormy night … just kidding. But it was dark out. It was just after midnight and Clemente was in the mood for a snack. Earlier, he’d been ejected by home-plate umpire Lee Weyer for arguing a called third strike in the fourth inning. (This is the main reason that, even though Clemente says the abduction happened during the May series, all signs point to the August series, because Clemente was ejected from only one game in both series and that was on August 8.)1 After being ejected, he left the ballpark and went back to the El Cortez hotel (where the Pirates were staying) alone. But other sources state that the Pirates as well as Clemente may have been staying at the Town and Country Hotel, which is near the freeway that runs right past San Diego Stadium.2

When he got back to his hotel room, he called his wife to tell her he was going to retire. His shoulder had been hurting him and he’d been thrown out of the game. She told him to “finish the road trip, then if you come back to Pittsburgh and don’t feel any better, it will be alright to quit.”3 Clemente said, “Okay, you’re the boss. But if I don’t feel any better when I get back to Pittsburgh then it’s all over.”4

Sometime after midnight, he grew hungry and decided to go out and get some food. He ran into Willie Stargell, who had just come out of a coffee shop with a bag of fried chicken. Stargell told Clemente that the chicken was good, and Clemente decided to get a bag for himself. Clemente purchased the chicken and started back to the hotel. It was then that he noticed a car following him. The car pulled up beside him and he was held at gunpoint by four men (although some accounts say three). He was forced into the back of the car and told to lie down on the floor. One of the assailants put a gun to Clemente’s chin and told him, “We’re going to teach you some manners.”

The kidnappers took Clemente to a park, which was most likely Balboa Park.5 He was told to get out of the car and strip, which he did except for his underwear. He was then forced over the hood of the car and held at gunpoint while the kidnappers went through his clothes. They took his wallet, along with $250 and the All-Star ring off his finger.6

Clemente was sure they were going to shoot him, saying “they already had the pistol inside my mouth.”7 But, he was able to talk his way out of the scary situation. He told them that he was a professional baseball player for the Padres because he thought that they might not know who the Pirates were. And upon finding Clemente’s Player’s Association card in his wallet, they believed that he indeed was a big-league ballplayer.

When the kidnappers found out that he was a major leaguer, their tone changed from threatening to nearly apologetic. Two of Clemente’s abductors were Spanish-speaking, and after talking to the men, they returned his wallet, along with the money and his All-Star ring.8 They even helped Clemente put his clothes back on and straightened his necktie for him.9 They then drove him back to within three blocks of the Pirates’ hotel and dropped him off.

But the bizarre events of that San Diego night aren’t quite over yet. There is still one last little twist. Do you remember how I said that the story begins and ends with fried chicken? Well, I wasn’t lying, because as Clemente walked away, he heard his abductors pull up behind him again. He thought that maybe they had changed their minds about letting him go, but that wasn’t the case. One of his kidnappers said, “Here’s your chicken,” and handed the bag back to Clemente, who took it, waited for the car to speed away, and then tossed the snack across the street.10 He went back to the hotel but didn’t report the incident to the police.

A CRIME DIVULGED

The day after the alleged kidnapping, if we are to believe that it took place on August 8, 1969, the Pirates and Padres had a break in their three-game series. The game on the 8th was the first game of the series. The next day, Saturday the 9th, the NFL San Diego Chargers had priority for the use of San Diego Stadium, so a doubleheader was scheduled to be played on the 10th. This break in the schedule may explain why Clemente (and Stargell) were up so late tracking down food. Although I can’t pretend to understand the late-night eating habits of young baseball players, this could be their normal activity whether there was a game the following day or not. But one thing did happen on the 9th; Clemente told a few people about the harrowing events from the previous night.

More than a year after the incident, on August 27, 1970, after the emergence of the Bill Christine article, the Pirates were in San Diego for the first time since the kidnapping became public knowledge. After a two-game series on the 25th and 26th, the 27th was a travel day for the Pirates as they headed north to San Francisco for a four-game series against the Giants. Before the Pirates left, though, the San Diego Police Department wanted to have a word with Clemente about the alleged kidnapping.

Clemente was questioned by San Diego police detective Hanly Pry on the 27th and he stated that before the Bill Christine article, which was published just two days after the one-year anniversary of the kidnapping, he had told only three other people about the incident. He said that the day after the kidnapping (August 9, 1969), he told teammate Jose Pagan, Pirates coach Bill Virdon, and umpire Lee Weyer (yes, the same umpire who had ejected him the previous day). It came to light that Clemente also divulged the incident to teammate Matty Alou and Pirates general manager Joe Brown.11

So why didn’t Clemente tell anyone other than a handful of people about the incident? And why didn’t he report it to the police? Clemente told Christine that “I haven’t told this story to many people because I figured if any of the four robbers heard about it they might be looking for our ballplayers when we go out there again.”12 Another article quoted him as saying, “why should I report it? I am alive, no?”13

As to why he finally decided to make the incident public, Clemente said that he “forgot about the whole thing until somebody brought it up. Then I figure I better tell the story so it be printed right.”14

And while the story may have been “printed right,” the validity, or lack thereof, is in the confusing details given. Whatever the actual reality of the incident is, Clemente’s biographer, David Maraniss, put it best in Clemente: The Passion and Grace of Baseball’s Last Hero, stating that the abduction “fit perfectly into the mythology of Roberto Clemente as a man of the people, respected even by urban desperados.”15

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted Baseball-Reference.com. Thanks to George Skornickel and to Craig C. Britcher of the Heinz History Center.

Notes

1 Associated Press, “Clemente’s Kidnapping Confirmed,” Pottstown (Pennsylvania) Mercury, August 28, 1970: 25.

2 Bill Christine, “Clemente Reveals Abduction,” Pittsburgh Press, August 10, 1970: 25.

3 Christine.

4 Christine.

5 “Clemente’s Kidnapping Confirmed.”

6 “People,” Sports Illustrated, August 24, 1970. https://vault.si.com/vault/1970/08/24/people.

7 “People.”

8 “Clemente Reveals Close Call with Kidnapers,” The Sporting News, August 22, 1970: 24.

9 “Clemente’s Kidnapping Confirmed.”

10 “Clemente’s Kidnapping Confirmed.”

11 “Clemente Reveals Close Call with Kidnapers.”

12 RetroSimba, “The Night Roberto Clemente Was Snatched in San Diego,” retrosimba.com, February 9, 2021. https://retrosimba.com/2021/02/09/the-night-roberto-clemente-was-snatched-in-san-diego/.

13 “Clemente Reveals Close Call with Kidnapers.”

14 “Clemente Reveals Close Call with Kidnapers.”

15 RetroSimba, “The Night Roberto Clemente Was Snatched in San Diego.”