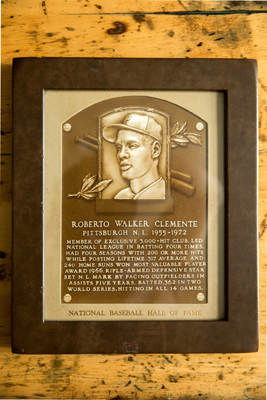

Roberto Clemente: First Player From Latin America Inducted in the National Baseball Hall of Fame

This article was written by Bill Nowlin

This article was published in ¡Arriba! The Heroic Life of Roberto Clemente (2022)

(Photograph by Duane Rieder.)

In the immediate aftermath of Roberto Clemente’s New Year’s Eve plane crash while on a mercy mission to Nicaragua, there were calls for him to be inducted by acclamation into the National Baseball Hall of Fame. His qualifications were never questioned; he was only the 11th player to reach 3,000 base hits and was a 15-time All-Star. The only thing standing in the way was a Hall of Fame rule that a player cannot become eligible for induction until five years after his playing career ended.

On January 2, 1973, Joe Heiling, the president of the Baseball Writers’ Association of America (BBWAA), said, “We feel that Clemente, like Sandy Koufax and Stan Musial, would be a first-ballot inductee, so why wait?” Secretary-treasurer Jack Lang said that BBWAA leadership had reached out to Commissioner Bowie Kuhn and that Kuhn had offered his “complete support.”1

Joseph Durso of the New York Times wrote that Clemente “doubtlessly will become the first Latin player elected to baseball’s Hall of Fame.”2

And the Boston Globe’s Harold Kaese wrote, with perhaps a bit more precision, “Prediction: Roberto Clemente will be the first Latin-American player in baseball’s Hall of Fame.”3

The sports editor of the Chicago Defender wrote that Clemente was “one of the many great black superstars, who never got the right break in the mainstream of publicity. But now that he is gone, his accomplishments on the field have assured him a sport in baseball’s Hall of Fame.”4

In the aftermath of Clemente’s death, the board of directors of the Hall voted on January 3 to amend the eligibility rules.5 An editorial in The Sporting News endorsed the idea, its final sentence reading, “If induction into the baseball shrine enhances Roberto’s reputation, his name will add luster to the Hall of Fame, too.”6

There were those who recommended not being so hasty. Among the first to speak out was Richard Dozer of the Chicago Tribune, who said he would vote against admission before the five-year period, giving a number of reasons, one of which was that Clemente’s children would then be ages 13, 12, and 9 and would then better “realize the scope of the honor. All they know now is that Daddy’s gone.”7

Bob Broeg, writing in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, noted how proud a man Clemente had been and suggested, “[T]he way I see it, to steamroller Roberto into the Hall of Fame now is really a disservice to the proud person who liked to feel that he was best in life, not in death.”8 Broeg argued that Clemente himself wouldn’t be able to appreciate an induction ceremony and that “[f]ive years from now, all of us could benefit anew by renewing the faith, so to speak, by a reminder and restatement of the compassion and consideration of the outstanding athlete and humanitarian who died on a mission of mercy to the helpless and homeless of Managua.”9

Those arguments notwithstanding, at a January 27 meeting, the Hall of Fame Committee of the BBWAA and the Hall of Fame Veterans Committee agreed to hold a special election.10

The results were reported in late March, 393 to 29 with two abstentions. It was the largest number of ballots cast in any Hall of Fame vote.11

The Associated Press story declared Clemente “the first Latin-American player voted into the Hall.”12

The actual induction took place at Cooperstown on August 6, as part of the annual ceremony. Others inducted that day were pitcher Warren Spahn, the sole player elected in 1973,13 Monte Irvin, voted in by a Special Committee on the Negro Leagues,14 and three selected by the Veterans Committee: umpire and executive Billy Evans, George “Highpockets” Kelly, and Mickey Welch.

Vera Clemente attended the induction ceremonies, along with her mother-in-law and her three sons. Described as speaking with “her composure shaken and her voice cracking under the strain,” she said, “This is Roberto’s last triumph.”15 The Los Angeles Sentinel offered her comments in some detail.16 Among those present was Mrs. Lou Gehrig.

THE FIRST LATIN AMERICAN PLAYER IN THE HALL OF FAME

Who was the first player from Latin America to be inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame?

Was it Ty Cobb, Walter Johnson, Christy Mathewson, Babe Ruth, or Honus Wagner? No, it was not. They were the first five inducted into the Hall of Fame, in the first class back in 1936. All were born in the continental United States.

The first person born outside the United States was inducted just two years later, in 1938 – Harry Chadwick, a pioneer/executive who came from Exeter, England.

In 1953, two more British natives were added to the Hall in the same class – executive Harry Wright (Sheffield) and umpire Tommy Connolly (Manchester). Wright had played baseball in Boston from 1871 to 1877.

In 1962 Jackie Robinson became the first Black ballplayer voted into the Hall.

Roberto Clemente had lived to see Satchel Paige added to the Hall of Fame in 1971, and both Josh Gibson and Buck Leonard added in 1972.

A native of Carolina, Puerto Rico, with his 1973 induction, Clemente was the first player from Latin America to be inducted into the Hall, via special election after his tragic death on December 31, 1972. As noted, also inducted in 1973 was Negro Leaguer and eight-year National League ballplayer Monte Irvin.

LATER PLAYERS FROM LATIN AMERICA IN THE HALL OF FAME

Four years after Clemente’s induction, Martin Dihigo of Cidra, Cuba, was inducted in 1977. Had the five-year waiting period been maintained, Clemente would have first become eligible in 1978, and thus might have been the second Latin American inductee.

The mission Clemente had been on when he lost his life inspired many, in Puerto Rico, throughout Latin America, and around the world. With no disrespect to Martin Dihigo, honoring Clemente in the Hall of Fame in 1973 was part of an outpouring of activity that resulted in many tributes that produced good works of one kind or another, such as the construction of Ciudad Deportiva Roberto Clemente in Carolina, Puerto Rico (Roberto Clemente Sports City).

It was Clemente’s dream to build such a sports complex, a dream that had been noted by the New York Times more than a year before his death.17 As early as February 20, 1973, Vera Clemente announced the securing of a 602-acre site in Carolina, Clemente’s hometown.18 An article on the History.com website says, “The Roberto Clemente Sports City has served more than one million children, including future major leaguers Bernie Williams, Ivan Rodriguez, Juan Gonzalez, and Benito Santiago.”19

After Clemente, it was 10 more years before the next player from Latin America was named to the Hall of Fame. Such players named since Clemente’s induction are:

- 1983 – Juan Marichal, of Laguna Verde, Dominican Republic

- 1984 – Luis Aparicio, of Maracaibo, Venezuela

- 1991 – Rod Carew, of Gatun, Panama Canal Zone.

- 1999 – Orlando Cepeda, of Ponce, Puerto Rico

- 2000 – Tony Perez, of Camaguey, Cuba

- 2006 – Jose Mendez, of Cardenas, Cuba

- 2006 – Cristobal Torriente, of Cienfuegos, Cuba

- 2011 – Roberto Alomar, of Ponce, Puerto Rico

- 2015 – Pedro Martinez, of Manoguayabo, Dominican Republic

- 2017 – Ivan Rodriguez, of Manati, Puerto Rico

- 2018 – Vladimir Guerrero, of Nizao, Dominican Republic

- 2019 – Mariano Rivera, of Panama City, Panama

- 2022 – Orestes “Minnie” Miñoso, of La Habana, Cuba

- 2022 – Tony Oliva, of Pinar del Rio, Cuba

- 2022 – David Ortiz, of Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic

Edgar Martinez was born in New York City but raised in Puerto Rico. He was voted into the Hall of Fame in 2019.

One can be sure that many more will eventually be so honored, given the obvious demographics in major-league baseball over the past 25-plus years.

Recent reports state that Hispanic or Latino ballplayers make up around 30 percent of current major-league players.20

As perhaps a point of interest, four natives of other countries are enshrined in the Hall of Fame:

- Fergie Jenkins (1991), born in Chatham, Ontario, Canada

- Barney Dreyfuss (2008), born in Freiburg, Germany

- Bert Blyleven (2011), born in Zeist, The Netherlands

- Larry Walker (2021), born in Maple Ridge, British Columbia, Canada

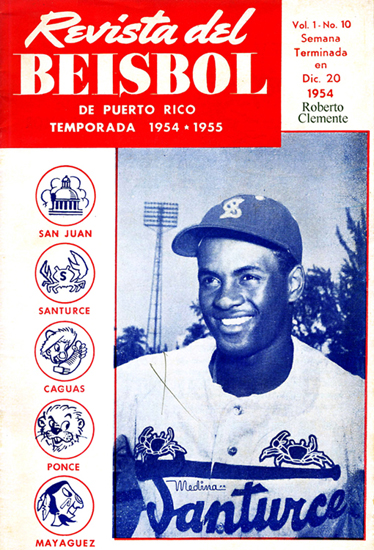

(Courtesy of Thomas Van Hyning.)

SIDEBAR: FIRST LATIN PLAYER IN THE HALL OF FAME?

Ted Williams was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1966, seven years before Roberto Clemente. Joseph Durso – in an article written the very day it was learned that Clemente had been killed in the airplane crash – said that Clemente would without doubt become “the first Latin player” elected to the Hall of Fame.

From the next day onward, newspaper accounts always referred to him as the “first Latin American player.” Why the distinction? We don’t know. Almost certainly, none of the writers had Ted Williams in mind at the time. It was nearly 30 years later before that question was raised.

In 2002, I wrote an article for the Boston Globe Magazine entitled “El Splinter Esplendido, Ted Williams’s Latino Heritage.”21 In it, I explored his family background, which included both maternal grandparents having been born in Mexico. He knew his grandmother Natalia Venzor, for whom Spanish remained her primary language. My research continued, and a much longer essay appeared in a book co-authored with eight other SABR members, The Kid: Ted Williams in San Diego.22

I ultimately devoted an entire book to the subject, building on that 2005 essay. Published in 2018, it was entitled Ted Williams; First Latino in the Baseball Hall of Fame.23 Most of the rest of this sidebar is drawn from this 2018 book.

Awareness that Ted Williams had been Latino began to spread. The National Baseball Hall of Fame gift shop offered a T-shirt for a while that listed Latino Hall of Famers, with Ted Williams top of the list.

A minor controversy arose in August 2005, when Major League Baseball didn’t seem to have gotten the message. Richard Sandomir led a story in the New York Times writing, “When Major League Baseball unveiled its ballot for the Latino Legends team Tuesday, the 60 nominees excluded two of the greatest Hispanic players ever: Ted Williams and Reggie Jackson.”24

MLB argued that neither Williams nor Jackson were publicly linked to their Latino heritage, that they didn’t “represent the Latin community.” Sandomir wrapped up his article: “Jackson, whose grandmother was Puerto Rican, said he is ‘proud of my Latin blood,’ but not upset at being left off the ballot. But he is offended by any suggestion by baseball about his connection to those roots. ‘They have no right to pass judgment on what I claim about my Latin heritage,’ said Jackson, whose middle name is Martinez. ‘I just don’t run my mouth off about it.’”25

What was MLB’s rationale? J.A. Marzán explained: “Sandomir cited Carmine Tiso, a baseball ‘spokesperson,’ who explained that lineage is not baseball’s standard for identifying a player as Hispanic: ‘[Baseball] … applied a litmus test that went beyond statistics: the nominees had to have a direct connection to their Latino heritage.’ A second cited spokesman, Richard Levin, said the players should ‘represent the Latin community.’ Tiso added a defense of Williams: ‘It’s not that he was ashamed of his heritage, but we felt that we didn’t find enough connection from Ted to that Latino heritage.’ Levin appended an additional consideration: that Williams’s name ‘would distort the ballot’ and ‘cause havoc’ because his ethnicity is not widely known.”26

One could mock the notion of resultant “havoc,” but the explanation offered by the Major League Baseball spokesmen shares similarity to that later rationally argued by scholar Adrian Burgos Jr. that Ted Williams should not be considered Latino because he “did not identify as Latino nor was he racialized as such during his legendary career.”27 Ted hadn’t had to anglicize his surname, suffer ridicule for his accent, or bear discrimination at contract time.

Ted Williams was able to live as Anglo – fairly easily, since he’d been largely raised as such. If he didn’t publicly identify as Latino, does that disqualify him from being considered Latino? We have the evidence that Ted knew he could have been considered Latino. As he wrote in his autobiography, “If I had had my mother’s name, there is no doubt I would have run into problems in those days, the prejudices people had in Southern California.”28 Ted Williams: First Latino in the Hall of Fame demonstrates that he did identify as partially Latino – but, for a cluster of reasons, informed by time and place, wanted to avoid that perception.

Burgos is by no means incorrect. He further argues that “it is also important that we do not rewrite the history of Latinos and baseball by retroactively inserting Williams because he chose not to do so on the grandest platform he was provided.”29 That platform was the occasion of his 1966 induction into the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Ted talked about the playground director who’d worked with him as a kid, his coach in high school, and other influences. He could have made something of his Latino heritage, but he did not. The absence of this acknowledgment could be considered underscored by his use of the bully pulpit to call for the recognition of Satchel Paige and Josh Gibson as “symbols of the great Negro players who are not here only because they weren’t given the chance.” Here was an opportunity for Williams to state what he, three years later, expressed in My Turn at Bat, that he himself could have suffered from prejudice, too.

One could perhaps understand that he wasn’t ready to throw open windows in public that he had long been accustomed to keeping closed. One could also argue that – had he been tempted – he might have preferred not to muddy the waters, the better to keep the focus on his point about the Negro Leaguers. They had suffered discrimination; he had not had to.

Needless to say, it’s a complex question. There is identity, and there is public acknowledgment of identity. If one wants to avoid being “branded” as of such-and-such a heritage, the human psyche is such that one can even deny something to the point where one’s own consciousness is deceived by the masking and denial. Williams never denied he was Latino; he just didn’t want to go there. Had he been born a couple of decades later, or lived a decade or two longer, this might have been otherwise.

Major League Baseball itself had perhaps changed its tune by 2012. On September 25, 2012, during Hispanic Heritage Month, Jesse Sanchez, a writer for MLB.com, released his “All-Time Latino Team.” The outfield featured Ted Williams in left field, Reggie Jackson in center, and Roberto Clemente in right field.30

Full-length Williams biographies by Leigh Montville (in 2004) and Ben Bradlee Jr. (2013) helped better establish the popular awareness of this side of Ted Williams’s ancestry.

All that said, Roberto Clemente was, in fact, both the first Latin-American player inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame and the first player publicly identified as Latino to have been inducted. That public identification mattered a great deal. It was Clemente who inspired thousands upon thousands of Latinos, in so many ways.

AN INSPIRATION TO LATINO PLAYERS OF ANY BACKGROUND

That detour aside, there is no question whatsoever that for the past near-half-century, it is indeed Roberto Clemente who has inspired other Latinos – players, fans of the game, and those writing about baseball, sport, and matters of history and society. He was in the forefront.

Adrian Burgos Jr., editor-in-chief of LaVidaBaseball.com, spoke of the ongoing impact that Clemente has had in Puerto Rico alone, on top of the players who have come through Ciudad Deportiva Roberto Clemente.

“One thing that’s really fascinating is that we saw a generation of players – Hall of Famers like Clemente, Cepeda – who weren’t able to enjoy big-money free agency. So Alomar and Pudge [Rodriguez] … they got to enjoy the money that came with being a star in the league. They’re also parlaying that into the development of baseball in Puerto Rico,” said Burgos.

“That’s how you honor Clemente, by making sure that the next generation has the opportunity, you give to the impoverished community, you seek out ways to help them have that opportunity.… It’s not trite, not passé, not rote, it’s deeply meaningful in the culture of Puerto Rico, particularly in baseball but also in education: How do you honor the spirit of Clemente? How do you carry on that tradition?”31

Both Edwin Correa and Carlos Beltran have followed in Clemente’s footsteps and established baseball academies of their own in Puerto Rico.32

BILL NOWLIN sadly never saw Roberto Clemente play, having grown up in an American League city (Boston) in the days before interleague play. (But he remembers his Topps baseball cards.) A lifelong Red Sox fan, he was a professor of political science and co-founder of Rounder Records, and has over the past 20 years become more active in writing and editing about baseball, primarily for SABR but also for a few other entities.

Notes

1 United Press International, “Writers Move to Induct Clement into Hall,” Boston Globe, January 3, 1973: 52.

2 Joseph Durso, “A Man of Two Worlds,” New York Times, January 2, 1973: 48.

3 Harold Kaese, “Press Ignored Clemente, Cooperstown Won’t,” Boston Globe, January 3, 1973: 51.

4 Norman O. Unger, “Great Hall for ‘Beeg Boy’?,” Chicago Defender, January 3, 1973: 24. This day’s edition of the newspaper misspelled the author’s first name as Noman.

5 “Way Paved to Put Clemente in Hall Now,” Washington Post, January 4, 1973: F6. The rule had been suspended once before, though at the time it was only a one-year rule – for the induction of Lou Gehrig after he had been diagnosed with ALS. That suspension allowed Gehrig to experience the induction while he was still alive. For more details on Gehrig’s induction, and other rule changes over the year, see Harold Kaese, “Hall Rules Suspended Twice, Changed Often,” Boston Globe, January 7, 1973: 107. Kaese’s own view, he said, was that making an exception “does not diminish the splendor of the Hall – which is kind of a paper peacock in any case – and shows that, after all, the hearts of most baseball writers are in the right place.”

6 “A Man of Quality,” The Sporting News, January 20, 1973: 12.

7 Richard Dozer, “Fame Vote Now Could Be Disservice to Clemente,” Chicago Tribune, January 5, 1973: C3.

8 As rendered in The Sporting News, see Bob Broeg, “Quick Enshrinement Disservice to Roberto,” The Sporting News, January 20, 1973: 38. The original article appeared as “Instant Enshrinement Is a Disservice to Clemente,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, January 7, 1973: 32. For comments from a couple of other sportswriters of the day, see Vince Guerrieri, “The Writers Are Bad”: Clemente and the Press,” in this volume.

9 Broeg, “Quick Enshrinement Disservice to Roberto.”

10 Jack Lang, “Writers to Cast Ballots on Clemente,” The Sporting News, February 10, 1973: 48.

11 Jack Lang, “Writers Okay Clemente Induction,” The Sporting News, March 31, 1973: 32. See also United Press International, “Clemente Makes Hall of Fame,” Chicago Tribune, March 21, 1973: F1, which reports on the reaction of Vera Clemente to the honor. She had flown to St. Petersburg for the announcement.

12 Associated Press, “Writers Vote Clemente Into Cooperstown Shrine,” Hartford Courant, March 21, 1973: 59A. It was reported that the majority of the votes against Clemente’s induction were accompanied by an explanation that the voter was opposed to waiving the five-year rule.

13 Associated Press, “Spahn Goes Solo to the Hall of Fame,” New York Times, January 25, 1973: F1.

14 Joseph Durso, “Irvin Named to Hall of Fame in Special Vote for Blacks,” New York Times, February 8, 1973: 55.

15 United Press International, “Clemente’s Widow Shaken at Ceremony,” Los Angeles Times, August 7, 1973: B3.

16 Milton Richman, “Mrs. Clemente Remembers Roberto,” Los Angles Sentinel, August 9, 1973: B2.

17 Murray Chass, “Clemente’s Dream: A Utopian Sports City,” New York Times, October 21, 1971: 62.

18 United Press International, “Site Picked for Clemente Sports City,” New York Times, February 21, 1973: 28. The land was provided by the government of Puerto Rico. Initial funding was provided by $500,000 donated by the Pittsburgh Pirates and “a local newspaper and bank.”

19 Christopher Klein, “How Puerto Rico Baseball Icon Roberto Clemente Left a Legacy Off the Field,” History.com, October 13, 2021. https://www.history.com/news/roberto-clemente-humanitarian-accomplishments-pittsburgh-pirates. Accessed January 20, 2022.

20 For instance, the Institute for Ethics and Diversity in Sports stated, “The percentage of Hispanic or Latinx players saw a decrease from 29.9 percent in 2020 to 28.1 percent on 2021 Opening Day rosters.” See Dr. Richard Lapchick, “The 2021 Gender and Racial Report Card,” Institute for Ethics and Diversity in Sports. 138a69_0fc7d964273c45938ad7a26f7e638636.pdf (tidesport.org), accessed January 21, 2022. According to an Infogram post in October 2020, the percentage was 31.9 percent. See https://www.routine.com/blog/post/mlb-player-demographics/, also accessed January 21, 2022.

21 Bill Nowlin, “El Splinter Esplendido, Ted Williams’s Latino Heritage,” Boston Globe Magazine, June 2, 2002.

22 Bill Nowlin, ed., The Kid: Ted Williams in San Diego (Burlington, Massachusetts: Rounder Books, 2005), published in collaboration with the Ted Williams (San Diego) Chapter of the Society for American Baseball Research.

23 Bill Nowlin, Ted Williams; First Latino in the Baseball Hall of Fame (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Rounder Books, 2018).

24 Richard Sandomir, “Williams and Jackson Omitted from Latino Ballots,” New York Times, August 26, 2005: D1.

25 Sandomir.

26 J.A. Marzán, “Ted Williams: Throw the Heat; Hold the Tortillas,” New English Review, November 2014. https://www.newenglishreview.org/custpage.cfm/frm/170995/sec_id/170995. Accessed January 20, 2022.

27 Adrian Burgos Jr., “No, Ted Williams Was Not Baseball’s First Latino Superstar,” The Sporting News, June 24, 2015.

28 Ted Williams with John Underwood, My Turn At Bat (New York: Fireside Books, 1969), 28.

29 Burgos.

30 Jesse Sanchez, “Clemente Heads All-Time Latino Team,” MLB.com, September 25, 2012. http://mlb.mlb.com/mlb/events/alltimelatino/index.jsp. Accessed January 20, 2022.

31 Chris Davies, “The Past, Present and Future of Baseball in Puerto Rico,” Hardball Times, April 17, 2018. https://tht.fangraphs.com/the-future-of-baseball-in-puerto-rico/. Accessed January 24, 2022.

32 For a story on the Beltran Academy, see Jason Margolis, “Baseball Academies Are Helping Puerto Rican Students on the Field and in the Classroom,” theworld, July 1, 2016. https://theworld.org/stories/2016-07-01/baseball-academies-are-helping-puerto-rican-students-field-and-classroom. Accessed January 24, 2022.