Roomie: The Relationship Willie Mays and Monte Irvin Shared

This article was written by Doron Goldman

This article was published in Willie Mays: Five Tools (2023)

Roomie – that’s Monte Irvin. He and I room together when the ball club’s on the road. Many’s the time I’ve hollered for him to get me out of what I’m in. Like the time we were posing for the team picture and a guy came up to me and said “Willie, I’m Jumble from the Daily Mumble,” and wanted me to predict the outcome of the world series. …

“Well,” Mr. Jumble from the Daily Mumble said, haven’t you any idea how the series is going to go?

“Yes,” I said. “I got an idea. First two games be played at the Polo Grounds. Then we go to Cleveland.” …

“All right,” he said, “then how would you compare your outfield with theirs?

“Roomie!” I yelled out. “Come over and take care of this man!”1

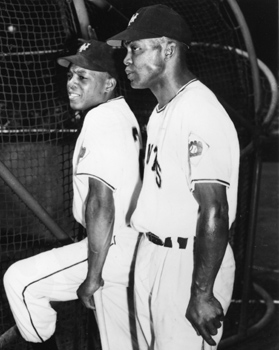

Monte Irvin offered the younger Willie Mays both advice and friendship. (SABR-Rucker Archive)

Willie Mays and Monte Irvin were lifelong friends. Although they likely first met as opposing players on a Southern baseball diamond, their first significant encounter was as roommates with the 1951 New York Giants. Irvin was Mays’ only road roommate in National League baseball, with the possible exception of early 1952, when Irvin was recovering from a broken ankle suffered in spring training and Mays played less than a quarter of the season prior to his Army induction.

Irvin played a significant part in the development of Mays’ character, both on and off the field. In turn, Mays was a galvanizing force in the life and livelihood of Irvin and on the Giants team, helping them overcome a 13½-game Dodgers lead in the 1951 pennant race and becoming the linchpin of a successful Giant demolition of the 1954 American League champion Cleveland Indians, winners of 111 games.

By 1955, Irvin’s career was beginning to wind down, while the 24-year-old Mays was still in the early stages of a 22-season National League career as arguably the best all-around position player in baseball history. Irvin played his last games for the Giants in June 1955 and retired early in the 1957 season after a final season with the 1956 Chicago Cubs, where he mentored another young Black superstar, Ernie Banks. Between Mays’ debut in May 1951 and June 1955, Irvin’s mentoring of Mays was comparable to the constant support and encouragement Mays received from Giants manager Leo Durocher. Reflecting back on his life, Mays titled the fifth of 24 chapters in his 2020 memoir, 24, “Honor Your Mentors: The Story of Leo Durocher and Monte Irvin.”2

Initial Encounters

Mays and Irvin were both born in Alabama, but Irvin’s family moved to New Jersey in 1927, four years before Mays was born.3 Mays and Irvin’s first recorded encounter likely occurred in Macon, Georgia, on April 19, 1948. The 16-year-old Mays briefly suited up for the Negro Southern League’s Chattanooga Choo Choos, who were playing Irvin’s Newark Eagles in Macon. Mays was cited as the “hitting and fielding star for the Chattanooga team.”4

Although this author has found no lineups or box scores to show whether Irvin played in this preseason exhibition game, it seems certain that he did, or at least that he became aware of the 16-year-old phenom, who was also the son of a semipro Black baseball player, William Howard “Kitty Kat” Mays.5

If Irvin did not notice Mays when their respective teams played against each other in Macon, he certainly should have become aware of him two months later, on Saturday, July 25, 1948, when the Eagles defeated the Birmingham Black Barons, 14-4, before 7,273 fans at Birmingham’s Rickwood Field. Now 17 years old, Mays played left field and batted third in the Black Barons’ lineup, and went 1-for-4 with two RBIs, while Irvin batted cleanup and played left field, going 4-for-5 with three RBIs for the victorious Eagles.6 According to several sources, Irvin and Mays played with each other on barnstorming teams as well.7

As recounted in Irvin’s 2007 book Few And Chosen, despite these earlier encounters, he and Mays really became acquainted when Mays joined the New York Giants in 1951.8 They first saw each other at a Philadelphia hotel on May 25, 1951, the day after Mays was summoned to New York from Minneapolis after a torrid .477 start to his 1951 Triple-A season, not unlike Irvin’s .510 start to his 1950 Triple-A season for the Jersey City Giants, the Giants’ other Triple-A affiliate.

Mays had arrived in New York on a flight from Minneapolis, met Giants owner Horace Stoneham and signed his contract at the midtown office of the Giants. He took a train down to Philadelphia, passing through Trenton, where he tore up the Class-B Interstate League in 1950, hitting .353.9

On May 25 Willie went 0-for-5 in his first game as a Giant and nearly collided with Irvin, who was playing right field alongside center fielder Mays, as the Giants won 8-5.10 According to some accounts, this is what led Durocher to tell Irvin and whoever else was playing right field to let Mays catch any ball he could reach.11

As is well-known, Mays started out his career 0-for-12 before hitting a home run off Warren Spahn, and was 1-for-26, an .038 batting average, before he really got going. Famously, Mays asked Durocher to send him down to the minor leagues, but Durocher said that as long as he managed the Giants, Willie would be his center fielder, adding that Mays was “the best center fielder I’ve ever looked at.”12

Mays followed his slump with a 9-for-24 tear and helped New York on an epic pennant drive. In some sources, Mays came first to Irvin for solace when he started so glacially, and Irvin both encouraged and advised him – either way, between Durocher and Irvin, Mays was given sufficient support and encouragement.13

When Mays joined the Giants in 1951, the team was 17-19 and in fifth place, a vast improvement from its start of 2-12, the last 11 of which were losses, but still well behind the front-running Dodgers. As Mays grew comfortable, the rest of the team became more comfortable around him. Irvin had started the season playing first base, and when Mays arrived, Irvin was moved to the outfield, starting in right field and ending up primarily in left, switching with Whitey Lockman, while Mays largely replaced Bobby Thomson, who settled in at third base.14 According to Irvin, “Willie joined the club in 1951 and it was instantly improved at four positions.”15

In later years, Irvin consistently stated that Mays was the team’s galvanizing force, the glue that brought the Giants together.16 In Irvin’s autobiography Nice Guys Finish First, he said that “when Willie Mays arrived, everybody saw right away what a sensational young budding star he was, and that really helped the racial situation all around.”17 Upon Mays’ arrival, the Giants had four Black players – Irvin, Mays, outfielder-third baseman Henry “Hank” Thompson, and Cuban catcher Rafael “Ray” Noble.18 And on June 3, 1951, Irvin, Mays, and Thompson were all on base at the same time, the first time that happened with three Black teammates. Later, in the World Series, Thompson, Irvin, and Mays replicated this notable event in the outfield.19

Irvin stated that the Dodgers were a clearly superior team, but that the Giants were able to play together as a team and support one another, which enabled them to come roaring back from a 13½-game deficit.20 After all, Irvin and Mays were the only two Giants to be inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame, and Irvin was elected as much for his Negro League play as for his play in the National League.

In contrast, five players in the 1951 Dodgers starting lineup – catcher Roy Campanella, first baseman Gil Hodges, second baseman Jackie Robinson, shortstop Pee Wee Reese, and center fielder Duke Snider – are Hall of Famers. While Campanella, like Irvin, had a substantial Negro League career, his Hall of Fame-worthy production occurred primarily in the National League, unlike that of Irvin. Meanwhile, both Robinson and Mays had only limited Negro League experience.

Mays’ 20 home runs, 68 RBIs, and .274 batting average, along with his already-stellar outfield play, certainly contributed a great deal to the Giants’ 1951 pennant drive. Informed commentators, however, generally have acknowledged that the Giants’ 1951 MVP was Irvin, with 24 home runs, a league-leading 121 RBIs, and a .312 batting average. For the season, Irvin was number one in WAR (wins above replacement) among Giants position players with 6.9, followed by Al Dark, Eddie Stanky, Thomson, and then Mays with 3.9.21

During the Giants’ season-ending 39-8 run, which included a three-game playoff win against the Dodgers, Irvin’s starring role contrasted with Mays’ late-season slump. He still won the Rookie of the Year Award. Starting on August 11, when the Giants began a long homestand, Irvin batted .322 with 10 home runs and 38 runs batted in, while Mays batted only .247 with 3 home runs and 16 runs batted in.22

Already, Mays had made several astonishing plays in the outfield, ones that Irvin, among others who played with Mays, rated more highly than his most famous outfield play, “The Catch,” in Game One of the 1954 World Series. Whether or not Mays was starring offensively, he was certainly leading the team in exuberance. On the last play of the 154-game regular season, Sid Gordon hit a routine fly ball to Monte Irvin, which would clinch a win for the Giants and at least a playoff with the Dodgers. According to Mays, “I went over from center as fast as my legs could go. … Monte was there, waiting. I shouted at him. He patted his glove a couple of times. I shouted some more. Then Monte made the catch. I jumped on him out of just plain joy.”23

October 3, 1951, and the 1951 World Series

The climax of the 1951 season was the three-game playoff series between the Giants and the Dodgers. Never before, and never again, would the 154-game regular season end with three New York teams all in first place, albeit the Giants and Dodgers tied for that position (those same three teams would be in the same exact position – the Yankees winning the AL and the Dodgers and Giants tied for first, albeit after a 162-game regular season – eight years later.

Once again, the Giants came from behind in the ninth inning to win the third game of the championship playoff – but by then, of course, the two NL teams were in San Francisco and Los Angeles). After splitting the first two games, the Giants trailed 4-1 in the ninth inning of Game Three. In what was later called the “Miracle of Coogan’s Bluff,” the Giants punctuated their amazing season-end comeback from a 13½-game deficit with a miracle rally culminating in Bobby Thomson’s game-winning homer off Ralph Branca.

Where were Irvin and Mays during this rally? Irvin made the only out, a foul popup against Dodger starter Don Newcombe with two men on base, while Mays knelt on deck as Thomson ended the game. Irvin later related that Mays was glad to have avoided being in a game-ending situation by virtue of Thomson’s shot heard ’round the world, as “his knees had been knocking so badly that he wasn’t at all sure whether he could have made it up to the plate.”24 In the clubhouse celebration after the Giants’ dramatic win, Mays drank champagne, and was overwhelmed by its effects. As Irvin could attest, when Mays went out, he drank Cokes.

The World Series between the Giants and the Yankees started the next day, October 4. In Game One, the Giants started Irvin in left field, Mays in center field, and Hank Thompson in right field – the first time three Black players appeared as a complete outfield in what was then considered “major-league” baseball. This milestone happened because Don Mueller, the Giants’ regular right fielder, broke his ankle the previous day after sliding into third base on a single to right immediately after Irvin’s popout and before Thomson’s blast.

Not only did the Giants bring down a racial barrier by virtue of their all-Black outfield, they did it in Yankee Stadium, against a home team that did not integrate until four years later with Elston Howard in 1955.

For Willie Mays, the 1951 Series was the second of five World Series he played in. His offensive performance in those World Series included no home runs and a .230 batting average.25 The Giants took a 1951 Series lead of two games to one, but the Yankees swept the last three contests to take the Series, four games to two, the third in a five-year World Series-winning streak that was unprecedented in major-league history and, to date, has never been repeated.

But for Monte Irvin, the Series was a standout performance, as he batted .458 with 11 hits in 24 at-bats, including a spectacular catch, and a steal of home in the first inning of Game One of the World Series. Despite the disappointing ending, it was a great season for the Giants and a magical beginning to the career of Willie Mays.

1952 – Willie joins the Army; Monte breaks his ankle

In spring training of 1952, the Giants seemed poised to potentially repeat their 1951 triumph over the Dodgers. Mays would be starting his first full season as Giants center fielder, with Monte Irvin now ensconced in left field beside him.

Unfortunately for the Giants, neither Mays nor Irvin would play a full season for the Giants in 1952. Willie Mays had a date with the military, after playing the first quarter of the season. The Giants started 1952 with a won-lost record of 26-8, thereby following up their end of 1951 stretch run of 39-8 – meaning that for roughly half a season, the Giants were 65-16!

For the season’s start, Mays had not played stellar baseball, hitting a mere .236 with four home runs – but even more surprising given the Giants’ smashing start was that Monte Irvin, fresh off his third-place finish in the 1951 MVP voting, was out of commission with a broken ankle suffered in an April 2 exhibition game against the Cleveland Indians.

In that fateful exhibition game, Irvin was perched on first base with a walk when Mays drove his own hit to right field. Irvin started to slide into third base but, realizing that there was no chance of being thrown out, abruptly stopped his slide – a big mistake. When Willie Mays and other Giants players came over to where Monte Irvin lay in the dirt near third base, they saw a grotesque sight – Irvin’s ankle was gruesomely sticking out and he had to be carried off the field.

Mays’ response was to start crying – and sources have differed as to the reason for his crying. Irvin, in his autobiography, claimed that Mays cried because he saw the chances of the Giants winning the pennant again flying out the window, along with a substantial postseason check.26 Most other sources say that Mays was distraught over his roomie’s horrible injury – and let us remember that Willie Mays was still only 20 years old!27

Furthermore, Mays already knew that he was going to the Army pretty early in the 1952 season, which bolsters the explanation that Mays’ crying had more to do with sadness over his buddy’s terrible injury than with the likely loss of the 1952 pennant, a pennant he would not be around to see to its completion.

Monte Irvin did return to the Giants in August 1952, and hit .310 but with only four home runs, tying Willie Mays in that slugging category. With the Giants missing a total of 36 home runs and 145 RBIs combined from Mays and Irvin (20 home runs and 100 RBIs less from Irvin, 16 home runs and 45 RBIs less from Mays), it is surprising that the Giants still came in second, only 4½ games behind the Dodgers. At various times, both Mays and Irvin extolled the managerial acumen of Leo Durocher; perhaps his best performance as skipper was in 1952, when two of his top stars, Mays and Irvin, missed most of the season.

1954 – World Series Sweep and “The Catch”

Mays remained in the military for the rest of the 1952 season and all of 1953, although Monte Irvin played with Willie Mays on Roy Campanella’s barnstorming team before the 1953 season and observed that Mays was still in top form.28

Irvin himself returned strongly in 1953, hitting .329 (a career high) with 21 home runs and 97 RBIs despite reinjuring his ankle on August 9 in a home-plate collision with Del Rice of the Cardinals and missing most of August and part of September.29 Despite Irvin’s comeback year, the Giants, without Mays and with lackluster pitching, dropped to fifth place in the standings.

Despite this poor showing, the Giants were looking forward to 1954 – when Mays would return and hopefully join with Irvin and a surging Hank Thompson (24 home runs, 74 RBIs, and a .302 batting average with a .967 OPS in 1953 while playing roughly two-thirds of the time) to bring the Giants back into contention.

In spring training of 1954, the Giants squad could hardly contain themselves, showing tremendous enthusiasm for Mays’ return. Perhaps manager Durocher, feeling the heat for 1953’s weak showing, was the most excited for Mays to rejoin the team, as Irvin indicated that “Willie Mays, of course, was Leo’s favorite. He was the only one who received special handling from Durocher. Leo’s relationship with other players, even those he liked was different from the one he enjoyed with Willie.”30 In a foreshadowing of the 1954 postseason, the Giants and the Cleveland Indians played during spring training, as they both trained in Phoenix and barnstormed home together before the start of the 1954 season.

In the early going, both Mays and Irvin were struggling to establish themselves – but Mays quickly went on a tear and, for the first time, showed himself to be a true superstar. Irvin, in contrast, showed that he was now on the downside of his career, with occasional key hits but a demonstrably declining overall performance.

Although Bobby Thomson had been traded away to the Milwaukee Braves, the acquisition of Johnny Antonelli in return bolstered the Giants’ pitching staff, as Antonelli had his first big season, winning 21 games, losing only 7, with a league-leading 2.30 ERA. Mays dominated National League pitchers, with 41 home runs, 110 RBIs, and a league-leading .345 batting average, beating out on the season’s last day teammate Don Mueller’s .342 in the batting race. Not surprisingly, Mays won the 1954 National League MVP for his stellar performance.

Meanwhile, Hank Thompson contributed 26 home runs and 86 RBIs, so that Monte Irvin’s 19 home runs and 64 RBIs with a measly .262 batting average, by far his worst Giants season so far, was good enough. It is also helped that James “Dusty” Rhodes, playing part-time in left field and increasingly spelling Irvin in the late going along with regular pinch-hitting duties, contributed 15 home runs, 50 RBIs, and a 1.105 OPS (slightly better than that of Willie Mays, whose OPS was 1.078 albeit in 401 more at-bats than Rhodes had).

For the only time in five seasons (1952-1956), the Giants beat out the Brooklyn Dodgers in the NL pennant race, winning 97 games to the Dodgers’ 92. Though the Giants were therefore five games better than the Dodgers, over in the AL, the Cleveland Indians posted 111 wins, 14 more than the NL Giants. Based on regular-season performance, the Indians appeared to have a decided advantage in the 1954 Series – but thanks especially to one unbelievable and now-legendary play by Willie Mays, and an outstanding performance by Dusty Rhodes, who pinch-hit for Monte Irvin on three occasions, the Giants turned the tables on the Indians with a four-game World Series sweep.

As Arnold Hano described so beautifully in his book A Day in the Bleachers, the catch that Willie Mays made on a 430-plus-foot drive off the bat of dangerous Vic Wertz in the eighth inning of a 2-2 tie in World Series Game One at the Polo Grounds was an amazing over-the-shoulder-grab, followed by a pirouetting, dead-on-accurate throw by Mays to not only stop an immediate tiebreaking score by Larry Doby as well as a likely triple or even inside-the-park home run by Wertz, but also to keep Doby from advancing beyond third base, as he potentially could have scored from second base on the catch itself.31

As in many instances of Willie Mays’ early career, Monte Irvin was at hand, playing left field next to Mays. In later years, Irvin depicted the catch itself as “something special”32 and he described Mays’ saying that “I had it all the way” as they both returned to the dugout at the end of the inning with the score still knotted at 2-2.33

Willie Mays also made a great defensive play on Wertz in the 10th inning, keeping the game tied so that Dusty Rhodes could come up in the bottom of the 10th and hit a 250-foot dying quail just over the left-field fence for a three-run, game-winning home run.34 Twice more, Dusty Rhodes would come up to pinch-hit for Monte Irvin – and he delivered, to the tune of two home runs, a run-scoring single, and seven RBIs in the Series, which became a rout of the Indians. Monte Irvin was finally left in the game to hit for himself and delivered a two-run single, driving in Don Mueller and Willie Mays, in the Game Four triumph that clinched the Series sweep for the Giants.

Without Mays’ amazing catch and throw off Wertz’s eighth-inning drive, the Giants would likely have lost Game One of the Series, and perhaps the whole Series would have turned out differently. As Monte Irvin and others have described about Mays, he could defeat you in so many ways – so even though he batted only .286 with four hits in that Series, one could argue that he rivaled Rhodes as the Series MVP, at a time when there was no such award.

Despite the greatness of Mays’ play on Wertz, others, including Monte Irvin, always maintained that Mays made better plays, even if this one was the most important, given its placement at a crucial juncture of the one World Series that Mays – and for that matter, Irvin and manager Durocher as well – would win in their Giants careers (and in Durocher’s case, in his entire career as a manager – though Durocher played on the World Series-winning 1934 Gas House Gang Cardinals). For Irvin, the best catch Mays made was in the summer of 1951 in Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field. Pirates first baseman Rocky Nelson hit the ball, and as Irvin described it:

Rocky hit the ball directly over Willie’s head in center field. At the crack of the bat, Willie turned and ran. When he turned and got ready to make the catch, the wind had taken the ball over to his right. He saw that he didn’t have time to bring his glove hand over to make the catch, so at the last minute he caught the ball in his bare hand on a dead run for out number three.35

Roommates No More

In 1955 the Giants, coming off their first World Series triumph in 21 seasons, were led by 23-year-old Mays and were hoping for a comeback season from the 36-year-old Irvin. Mays delivered on his part of the bargain, crashing 51 home runs, the first of two 50-homer seasons in his career, with 127 RBIs, a .319 batting average, and a 1.059 OPS, the second straight league-leading OPS for Mays.

For Irvin, though, it was another story. After a lackluster start to 1955, with a .253 average and only one home run in 51 games, he was sent down to Minneapolis of the American Association. Although Irvin revived in Minneapolis and helped lead the Millers to a Junior World Series triumph under the managerial leadership of soon-to-be-Giants skipper Bill Rigney, Irvin’s Giants career – and his rooming with Willie Mays – was over. The Giants finished in a distant third place, 18½ games behind the eventual World Series champion Brooklyn Dodgers, who started the season with a 22-2 record and were never headed.

Irvin would go on to have a decent comeback season with the 1956 Chicago Cubs, where he helped mentor a young Ernie Banks, but his playing career ended after four games with the 1957 Hollywood Stars, a Brooklyn Dodgers affiliate, when his back acted up. Mays no longer had either of his two main mentors – manager Durocher had been let go at the end of the 1955 Giants season – but the Say Hey Kid was by 1956 a fixture in the Giants lineup for many more seasons.

By 1956, Mays was mentoring others, notably Giants rookie first baseman Bill White, and winning the first of four straight National League stolen-base titles and putting together two straight “30-30” (30 home runs, 30 stolen bases) seasons in 1956 and 1957. No major leaguer had posted a 30-30 campaign since Ken Williams did it for the St. Louis Browns in 1922.

The Relationship Between Willie Mays and Monte Irvin

Irvin and Mays had a mutually supportive relationship. When Mays arrived in New York, Irvin “took him under his wing” – and it is unquestioned that no teammate was more important and influential in the development of Mays, on and off the field, in his formative major-league years.36

In the first Willie Mays/Charles Einstein collaboration, Born to Play Ball, which was released in 1955, Mays credited Irvin with teaching him a great deal about outfield play, as well as how to steal home, which Irvin did five times during the 1951 season and in the first inning of Game One of the World Series against the New York Yankees.37

As Mays described, Irvin taught Mays how to aim his cutoff throws at the cutoff man rather than all the way home, with the result being Mays’ amazing throw to nail Billy Cox at the plate in a 1951 game against the Dodgers. According to Mays, “I came out of a turn and saw Whitey Lockman and threw at him. Lockman was the cutoff man. He just stepped to one side, let the ball ride through to the plate, and we had Cox.”38

Yet another conversation between Mays and Irvin involved the older, more experienced Irvin imparting surprising advice – that it was sometimes easier to steal home when a left-handed hitter was at-bat, even though a right-handed batter blocks the catcher’s view. According to Irvin, if a left-handed pull hitter was at bat, the third baseman would play wide of the bag, allowing him to take a bigger lead off third base.39

From the outset, Mays was a willing student, asking Monte Irvin for the tendencies of each hitter and seeking guidance in the outfield on positioning.40 Although Mays had a long way to go before establishing himself as the premier offensive and defensive center fielder in major-league baseball, the seeds were planted. As for hitting, Mays told Sporting News correspondent Joe King that “(W)hen I first came up, I didn’t hit well and I didn’t know too much about the league and Monty [sic] would always sit beside me and tell me things.”41

From the beginning of their time together, the teammates had a supportive, friendly, and at times even playful interaction. Upon beginning his major-league tenure in a big slump, Mays knew that Irvin would know how to counsel him and that Durocher wanted Mays to stay no matter what he hit. Mays knew that Irvin would “run interference” for him wherever they went, as Irvin “preached to Mays the virtues of handling himself with class and dignity on and off the field.”42 At the same time, Irvin recognized that Mays was a sensitive young man and would not criticize him but rather suggest “If it were me … I’d do it this way” when Irvin thought Mays had done something wrong.43

At home in New York in 1951, Mays lived with David and Ann Goosby near the Polo Grounds, where he was under the watchful eye of boxing promoter and former Negro League official Frank Forbes.44 Even there, Irvin was still a significant influence, vetting Mays’ activities, including after-hours bar-hopping and dating. Mays’ many autobiographies as well as his comments when Irvin died in 2016 suggested that Irvin had taken care of him and made sure he did not make serious mistakes in his day-to-day life.

Mays described how Irvin would invite him to his New Jersey home, and how the two would take walks together. “We’d walk through a park near his home in New Jersey talking about baseball and life. He made sure that I didn’t go into the wrong crowd. You don’t know as much as you think you know when you’re young, and he was my mentor and made me aware of what I could and couldn’t do.45

Irvin related going to Toots Shor’s, a favorite “watering hole” where athletes, especially baseball players, were alternatively insulted and protected by owner and New York Giants fan Shor. According to Irvin, he and Mays were welcomed there in those early integration days but knew they were seated on the periphery. “Now it wasn’t exactly balanced there. Willie Mays and I rarely sat all that close to Joe DiMaggio’s or Mickey Mantle’s table over at Toots’ place but we were there.”46

In contrast, Mays and Irvin often went together to Harlem nightspots like Small’s Paradise and Red Rooster, where, according to Mays, Irvin “called ahead to restaurants and told them so that when I got there … they had a Coke with a cherry waiting for me. They said, ‘No drinking.’ Monte had told them.”47

But there was a lighthearted side to their relationship as well. In a September 1954 article, Mays told sportswriter Milton Richman about games that he and Irvin would play with each other. In “distance,” whoever hit the farthest in batting practice “wins all the pop he can drink in the clubhouse. Loser pays for the pop. We got one rule, though. A man must drink his winnings the same day. Else he don’t get ’em.”48

On the road, they would play “Captain of the Room,” in which the player who got the most hits in the game that day has to take care of bags, get newspapers, and turn on the radio.49 As related by Irv Goodman in Sport magazine, Irvin, “his closest friend on the team, grabbed Willie in the shower room and scrubbed his butt with a coarse-haired floor brush. Willie roared with laughter throughout the ordeal, and the rest of the team, witnessing the byplay, ate it up.”50 What did Mays do to earn this treatment from his roomie? He made a game-saving catch.

As described by biographer James Hirsch, Mays had a “catalytic effect” on Irvin.51 If Irvin was in a bad mood, Mays would dispel it with music, whether sung by him or put on his portable phonograph, or suggest games or other diversions for Irvin. Mays’ presence would lift Irvin’s mood, as Irvin stated: “Willie gave me a lift. …You always knew when he was around, because the love of life just flowed out of him, and it got to the point where it was a pleasure to come to the ballpark every day.”52

Later in Mays’ career, after Irvin had been retired for 11 years and was just starting his stint as an assistant director of promotion and public relations to soon-to-be-former Baseball Commissioner William “Spike” Eckert, he reminisced about his career in an interview with New York Times Pulitzer Prize-winning sportswriter Arthur Daley. After relating Mays’ devastated reaction to Irvin’s broken ankle, Irvin said that “[T]he two greatest guys I ever met in baseball are Willie Mays and Ernie Banks. They are joys to be with.”53

Most importantly, when Mays faced racial prejudice as a young Giant, Irvin was there – to counsel him, and to defuse the situation. Author Roger Kahn told the story of Mays watching a dice table in a Las Vegas casino that the Giants visited during spring training in 1954. According to Kahn, he was told by a casino security chief to get Mays away from the tables because of his race, with the chief using the ugliest of racist epithets. Kahn reacted with outrage and brought Irvin into the situation. Not only did Irvin get Mays out of the casino, but he also prevailed upon Kahn not to tell this story for many years. In Irvin’s view, the publicity could only cause more trouble for Mays, as “[W]illie is only twenty-three. If you write what happened at the hotel, you could put Willie in the middle of a huge racial storm. I think it would be too much for the kid.”54

In 1954 Mays and Irvin went into business together, purchasing a liquor store in Brooklyn that they called Willmont Liquors. Surprisingly, Irvin and Mays went to Howard Cosell, who was practicing law before embarking on his broadcast career, for advice. Along with being a self-aggrandizing storyteller, embellishing his role in the transaction – from helping to arrange the transfer of the store to Harlem (which required a more expensive liquor license) to involvement in the store purchase itself – Cosell was viewed by both Mays and Irvin as an annoying person.55 The liquor store was short-lived, as Mays and Irvin sold it the next year.

Irvin enjoyed a notable post-playing career and remained one of Mays’ close friends. At many events where Mays was honored, Irvin was there – for Willie Mays Day at the Polo Grounds on May 3, 1963, for an August 1979 event at the Polo Grounds houses on 155th Street, and for Mays’ Hall of Fame induction on August 5, 1979.56

Both Irvin and Mays were in the initial group of 38 inductees for the National Black Sports Hall of Fame in 1973,57 and on October 14, 1973, Irvin was present for the last hit of Mays’ major-league career, in Game Two of the 1973 World Series, with Irvin now an assistant to Commissioner Bowie Kuhn and Mays finishing up with the Mets. In a column by Arthur Daley, Irvin was quoted as follows: “I saw you make your first hit … and I’ve seen you make your last one. Confidentially, Willie, the last one was easier to follow.”58 As Mays’ first hit was a “titanic blast over the Polo Grounds roof” and his last was a “splash up the middle for a run-scoring single,” Irvin’s wry assessment was spot-on.59

An Assessment

In a documentary film about Mays released in 2022, the role of Durocher in Mays’ development was prominently featured but no mention was made of Irvin. This runs counter to Mays’ frequent commentary of the important role Irvin played in his early development and to the comments of Bobby Thomson and others.

According to Thomson, “[T]hey always gave Leo credit for putting his arm around Willie and bringing him along. From what I saw, it seemed to me that Willie had an awful lot of respect for Monte. Monte was like a father to him.”60

Similarly, 1954 World Series hero Dusty Rhodes said that “[M]onte roomed with Willie and had a lot of influence on him. Monte was like an old professor. When he talked, you listened. He helped Willie get straightened out.61

While Durocher was undoubtedly an important influence on Mays, the skipper also had a downside. He was a well-known lady’s man, agitator, and “man about town” who ran with a “fast crowd.” Irvin’s reputation was always stellar – as a ballplayer and as an individual. Most recently, Mays said that “Monte taught me how to treat others and how to be treated. He played the game right and treated people right. He was a thinker. Everyone respected him. He made sure I didn’t get into trouble.”62 And listen to Durocher himself, a man known to be a self-promoter, speaking at an event that Irvin also attended: “Monte Irvin has as much to do with Willie’s success as I did.”63

Neither Irvin nor Mays was known to be confrontational about issues of civil rights. When Jackie Robinson wrote the book Baseball Has Done It in 1964, he interviewed Irvin as one of several key figures in baseball’s integration. Irvin stated that “I can’t for the life of me understand why I and the others, including Willie, didn’t protest more than we did” about incidents when they were segregated from their teams (emphasis added).64 Irvin went on to say that “[b]aseball has done more to move America in the right direction than all the professional patriots with their billions of cheap words. Baseball has proved that it can be done.”65

Mays declined to be interviewed for Robinson’s book. According to Robinson, “Willie didn’t exactly refuse to speak. He said that he didn’t know what to say.”66 Robinson editorialized that Mays and Maury Wills, another nonparticipant in the book, “did not wish to stir things up.”67 As with the racial incident in Las Vegas, both Mays and Irvin were more likely to speak with their activities as participants than with their voices as protesters.

As he reflected on that incident, Kahn characterized Irvin thusly: “[I]t was his way to avoid confrontations and to strive for civil-rights progress by diplomacy, so to speak.”68 When Kahn spoke to Mays after Kahn had revealed the incident in Las Vegas years later, Mays asked that he not be associated with the reaction its revelation might cause, saying, “I wasn’t much for controversy. Not then. Not now, either. I guess not ever.”69

When Irvin died in 2016, Mays did not show up at his memorial. But it was not because he was otherwise busy or because he deemed it unimportant. Rather, it was because he was too choked up to be there. He sent in his commentary, as follows:

Your [sic] all going to hear a lot of things about Monte Irvin today. There is much to be said. He was a good man, a good father, a good baseball player and a great friend. …

Monte taught me without directly teaching me. He taught me without preaching or lecturing or even without me knowing that I was learning. …

Monte was wise and generous and tough as they come. He was all the things that you’ve heard, and he was more. There will never be another Monte Irvin.70

The same, for somewhat different reasons, could be said of Mays – as an all-around player, as a center fielder, as the quintessential five-tool-player, there will never be another Willie Mays.

DUKE GOLDMAN is a longtime SABR member whose research focuses on the Negro Leagues and the process of baseball integration. Duke is working on a biography of Monte Irvin for McFarland & Co.; therefore, the article in this volume on Willie Mays and Monte Irvin is right up his alley.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to acknowledge the friendship and support of late SABR member Alan Kaufmann, who was planning to contribute to volumes like these until his sudden passing.

NOTES

1 Willie Mays, as Told to Charles Einstein, Born to Play Ball (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons,1955), 6-7.

2 Willie Mays and John Shea, 24 (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2020), 59.

3 Monte Irvin with James A. Riley, Nice Guys Finish First (New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, Inc., 1996), 14.

4 Chattanooga Daily News, April 20, 1948: 13, cited in Rocco Constantino, Beyond Baseball’s Color Barrier (Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield, 2021), 80.

5 John Saccoman, “Willie Mays,” in The Team That Time Won’t Forget (Phoenix: Society for American Baseball Research, 2015), 124.

6 http://www.retrosheet.org. Negro League Seasons accessed December 21, 2022.

7 See, e.g., Born to Play Ball, 43 (Willie Mays: “I got to play against and with some pretty fair ballplayers, not only while I was with the Barons, but a year or so later on, when Roy Campanella took me on for his barnstorming team during the winter months. I met Monte Irvin that way. …”); James S. Hirsch, Willie Mays (New York: Scribner, 2010), 70. (After the 1950 season, Piper Davis “rounded up some players to compete against major leaguers on a barnstorming tour. The games allowed Mays to meet two black players with the New York Giants, Monte Irvin and Hank Thompson.”)

8 Monte Irvin with Phil Pepe, Few And Chosen (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2007), 93: “The first time I ever set eyes on Willie Mays was when he joined the New York Giants in May 1951, but I had heard a lot about him by then.” (bold in original). Perhaps at age 88, Irvin did not remember the earlier encounters he had with Willie Mays.

9 Hirsch, 92-93.

10 Some sources, including a contemporary newspaper account, state that Mays and Irvin did collide in the outfield, but the game accounts of the New York Times and The Sporting News clearly indicate that they did not. See W. Rollo Wilson, “‘Sorta Scared’ He Says,” Pittsburgh Courier, June 2, 1951: 15 (“He made several nice catches and in his zeal to make good had a collision with right fielder Monte Irvin in the ninth inning. …”); Charles Einstein, Willie’s Time (New York: J.P. Lippincott Company 1979), 41 (“Against the Phillies in his first game as a Giant … he ran into teammate Monte Irvin. …); John Drebinger, “Polo Grounders Trip Phils 8-5, With 5-Run Splurge in Eighth,” New York Times, May 26, 1951: 24 (“In the ninth, however, Mays had a close call when his great speed almost brought him into collision with Monty [sic] Irvin on Waitkus’ smash into right center); “Arrival of Mays Starts Thomson on Batting Spree,” The Sporting News, June 6, 1951: 11. See also Ray Robinson, The Home Run Heard ’Round The World, (New York: HarperCollins Publishers 1991),122 (describing the May 25, 1951, game, states that “on one play [Mays] ran right up Irvin’s back as he went for Eddie Waitkus’ liner.”)

11 Robinson, 123. “After the [May 25] game, Leo told Irvin and Thomson that in the future they should let Mays take everything that came near him in center field. He’s got the range, said Durocher, you guys just guard the lines.”

12 Paul Dickson, Leo Durocher (New York: Bloomsbury 2017), 206; Hirsch, 103.

13 According to Hirsch, 95, Mays was sulking on the way home from Philadelphia after his 0-12 start and “Irvin tried to relax him. ‘Listen man,’ he said. ‘We won three in a row without you hitting. Now figure it out. As long as we hit, we don’t win. Only trouble’ll be if you get a hit.” In Mays’ 1966 autobiography, he says that Irvin suggested that Mays guess fastball and swing at the first pitch against Spahn, the result being Mays’ first hit and home run. Willie Mays as told to Charles Einstein, Willie Mays (New York: E.P. Dutton & Co., Inc. 1966), 94.

14 Irvin was moved to left field for the first time on May 21, 1951, with Whitey Lockman simultaneously moving to first base. On May 25, Mays was put in center field, with Bobby Thomson switched to left field and Irvin to right field. Irvin played both right and left field between Mays’ debut and late July, at which point he played left field for the entire 1951 pennant stretch drive. Baseball-Reference.com Game Logs for Monte Irvin 1951.

15 “Mets Plan Sentimental Party for Mays,” Chicago Defender, September 15, 1973: 28.

16 See, for example, Joe King, “Giants Bolstered, but Rise Depends on Irvin’s Ankle,” The Sporting News, February 17, 1954: 17. Monte Irvin quoted as follows: “Willie gives us a lift. … I don’t only mean those impossible catches he makes. I mean the way he can get everybody loose in the clubhouse and make us laugh and work up a spirit.

17 Irvin, 129.

18 To make room for Willie Mays, the Giants sent down Black shortstop and former Black Barons teammate Artie Wilson. Irvin stated that there was an “unwritten quota system that limited the number of black ballplayers on a ballclub.” Irvin, 142. According to Hirsch, 79, Wilson later said that he had “urged Durocher to call up Mays and that he would rather play in the Pacific Coast League than sit on the bench in the majors.” Wilson played through 1957 primarily in the PCL but never returned to the major leagues, finishing his New York Giants career with four hits in 22 at-bats.

19 Hirsch, 137.

20 Arthur Daley, “Another Pioneer,” New York Times, September 1, 1968: S2. Quoting Irvin: “[W]e never had the slightest idea when our drive started that we could catch the Dodgers. They had the equivalent of an all-star team, and we were merely trying to make it close.” See also “The World of Sports,” Alabama Tribune, October 12, 1951: 7. “The Giants are the Cinderellas of baseball, but they became so because they were united in purpose, well-balanced and daringly managed.”

21 Baseball-Reference.com 1951 New York Giants Statistics. Pitchers Sal Maglie with a 6.6 WAR and Larry Jansen with a 5.5 WAR were also ahead of Mays, leaving him seventh in WAR among all 1951 Giants players.

22 Stan Jacoby, “The Numbers Say It Ain’t So, Bobby: Did ’51 Giants Steal the Pennant?” New York Times, March 4, 2001: SP 11.

23 Born to Play Ball, 69.

24 Irvin, 159.

25 Baseball Reference.com Postseason Game Logs for Willie Mays. Note that Mays’ World Series totals now include 3 at-bats in the 1948 Negro World Series for the Birmingham Black Barons.

26 Irvin, 171.

27 Hirsch, 148. A photograph of the play shows Mays walking off the field with Indian Harry “Suitcase” Simpson’s arm around him, both of them tearing up. “Willie Mays never made it to second base. When he saw and heard the calamity at third, he collapsed to the ground, pounded on the dirt, and began to cry.” It certainly appears that Mays was upset over the horrible injury his roomie had just sustained as well as perhaps his role in it.

28 Hirsch, 159.

29 Arch Murray, “Monte’s Exploits in Orient Cheered at Polo Grounds,” The Sporting News, November 18, 1953: 18.

30 Irvin, 155.

31 Arnold Hano, A Day in the Bleachers (New York: Da Capo Paperback edition 1982), 116-125.

32 Irvin as told to Pepe, 98.

33 Irvin, 181.

34 Hano, 141-142.

35 Irvin, 182. In Willie Mays and John Shea, 92, coauthor Shea states that Irvin considered a catch by Mays off the bat of Dodger Bobby Morgan in 1952 to be Mays’ best catch. Irvin does describe that catch in his autobiography, but says it was made in 1954, and makes it sound as if he was there. Irvin, 183. According to Hirsch, 149-150, Irvin was in his hospital bed when Mays made his play on Morgan on April 18, 1952, barely over two weeks after Irvin broke his ankle. Based on this evidence, the author concludes that the catch off the bat of Rocky Nelson was the best catch Willie Mays made in Monte Irvin’s presence.

36 Mays and Shea, 61-63.

37 Born to Play Baseball, 21-22, 48-49.

38 Born to Play Baseball, 22.

39 Born to Play Baseball, 49 (stealing home normally against right-hand hitter); Hirsch, 107 (easier to steal when lefty pull hitter at the plate).

40 Hirsch, 107.

41 Joe King, “Should Be Better Fielder Insists Glove Whiz Willie,” The Sporting News, January 19, 1955: 9.

42 King, “Should Be Better Fielder Insists Glove Whiz Willie.”

43 Hirsch, 120.

44 Hirsch, 114-115.

45 Mays and Shea, 63.

46 Roberta J. Newman and Joel Rosen, Black Baseball, Black Business (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi 2014), ix-x.

47 Mays and Shea, 63.

48 Willie Mays as told to Milton Richman, “I’d Play for Nothing,” This Week Magazine, September 12, 1954: 16. Clipping in Willie Mays player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame, 1951-1965.

49 Mays as told to Milton Richman, “I’d Play for Nothing.”

50 Irv Goodman, “Is There a Willie Mays?” Sport Magazine, October 1954: 69. Clipping in Willie Mays Hall of Fame player file, 1951-1965.

51 Hirsch, 122.

52 Hirsch, 122.

53 Arthur Daley, “Another Pioneer,” New York Times, September 1, 1968: S2.

54 Roger Kahn, Memories of Summer (New York: Hyperion, 1997), 258-261. The story is rendered there in complete detail; Willie Mays was not yet 23 when the incident happened in late March of 1954.

55 See “J.G.T. Spink, “Personal Counsel to Players,” The Sporting News, August 10, 1955: 6. Cosell not only claimed falsely that he helped Irvin and Mays with the purchase of the liquor store, but he also suggested that he played against Irvin in high school. The reader can draw their own conclusions. Mark Ribowsky, Howard Cosell (New York: W.W. Norton & Company), 71-73 (quoting Irvin saying “[H]e was the only person I ever met during my career that I disliked. I mean really disliked.”

56 Monte Irvin, “Batting The Ball,” New Pittsburgh Courier, May 11, 1963: 8. (Irvin describes attending Willie Mays Day); Michael Givens, “Say Hey! … Willie!” New York Amsterdam News, August 11, 1979: 53 (Irvin attending event honoring Mays at the Polo Grounds Houses).

57 “38 Athletes Named to Black Hall of Fame,” New York Times, June 29, 1973: 33.

58 Arthur Daley, “Twilight of the Gods,” New York Times, November 4, 1973: S2.

59 Daley, “Twilight of the Gods.”

60 Irvin, 131.

61 Irvin, 131.

62 Mays and Shea, 63.

63 Durocher quoted in “Willie Mays Returns to Harlem,” Columbus (Georgia) Times, August 31, 1979: 24.

64 Jackie Robinson, Baseball Has Done It (Brooklyn: Ig Publishing, paperback edition 2005), 100.

65 Robinson, Baseball Has Done It, 101.

66 Robinson, Baseball Has Done It, 209.

67 Robinson, Baseball Has Done It, 208.

68 Kahn, 259-260.

69 Kahn, 261-262.

70 John Shea, “Willie Mays’ Heartfelt Words for Mentor Monte Irvin,” SFGate.com, May 2, 2016. https://www.sfgate.com/giants/article/Willie-Mays-heartfelt-words-for-mentor-Monte-7388040.php. Accessed February 3, 2022.