Roy Tucker, Not Roy Hobbs: The Baseball Novels of John R. Tunis

This article was written by Philip Bergen

This article was published in SABR 50 at 50

This article was originally published in The SABR Review of Books, Vol. 1 (1986).

A person’s first impression of baseball literature usually comes from library books, usually from the juvenile fiction section. Judging from what I see as a librarian, there are no more series of baseball books being published today for 8- to 12-year-olds. But if you are a bit older than the video generation, you may remember the Duane Decker Blue Sox series, each book centering on an individual player from that team. Perhaps you remember the Bronc Burnett series by Wilfrid McCormick or the Chip Hiltons written by basketball coach Clair Bee, rather unrealistic accounts of teenagers playing for high school or American Legion honors.

These boys played other sports (and starred in those, too), abstained from social contact with girls, and hung around with their chums, to use a word which fit in well with that milieu. Fatherly coaches explained “inside baseball” didactically, and usually a glory-seeking teammate or revengeful rival provided the plot’s conflict, which invariably came down to a hit in the bottom of the ninth inning (or a strikeout if the hero was on the visiting team). These books were entertaining, easily read, and quickly forgotten.

Certain authors were not so easily digested. Ralph Henry Barbour’s sporting novels, while formulaic, described the world of the privileged at the turn of the twentieth century in fascinating terms, mixing accounts of ball games with life at New England prep schools, class distinctions, and a snug sense of a time gone by forever. Barbour’s books were fun to read and thought provoking. So were those of John R. Tunis.

John R. Tunis today is regarded as out-of-date for today’s youth, and perhaps he is. His novels have been incorrectly written off as typical of all boys’ sports fiction, full of derring-do by wildly implausible heroes living in a make-believe world. It does Tunis a disservice to be classified like that, both as an author and as an instructor to the youth of his time.

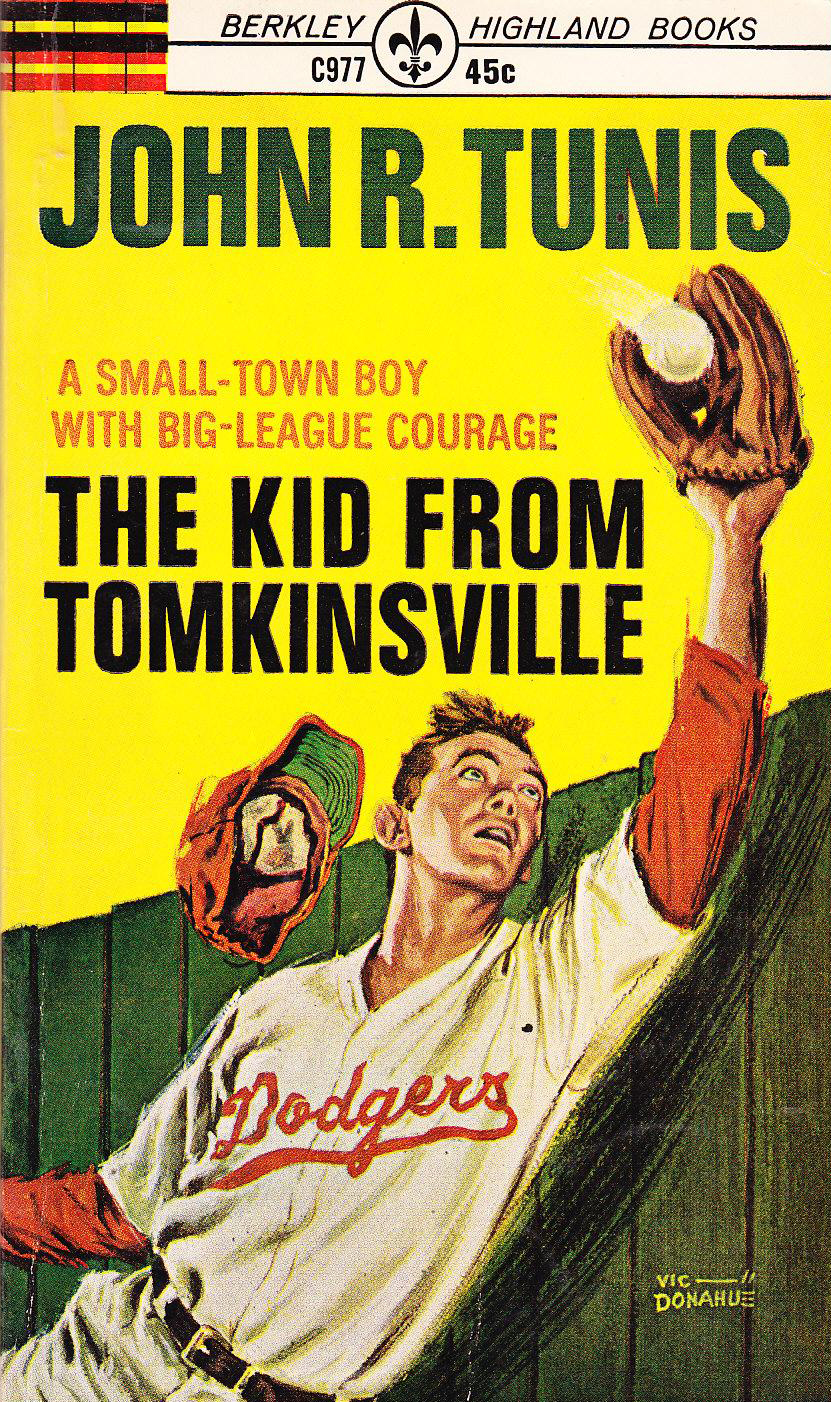

Examining Tunis is much easier today than with other boy’s authors. Tunis wrote nine baseball novels in the period from The Kid From Tomkinsville (1940) to Schoolboy Johnson (1958) and many of them are still available with a reasonable amount of searching. In addition, students of Tunis are fortunate enough to have his 1964 autobiography, A Measure of Independence, which provides an insight to the man and his career.

As with Ralph Henry Barbour, John R. Tunis was born in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in 1889, the son of a Unitarian minister. After his father’s death, when Tunis was 6, his mother boarded Harvard students, an occupation which provided income and an impetus for her children to value education:

As with Ralph Henry Barbour, John R. Tunis was born in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in 1889, the son of a Unitarian minister. After his father’s death, when Tunis was 6, his mother boarded Harvard students, an occupation which provided income and an impetus for her children to value education:

Education was her whole being, she believed in it with a passion that not many persons have for anything today. It was a source with her. She held it with both hands, cherished it. That we should receive an education also was her principal aim in life, all her energies were bent toward that goal, to this end she dedicated her tremendous determination. Of course we were going to college! Of course we were going to Harvard! The only question was how.

From his grandfather Roberts, Tunis learned to appreciate American history and the Boston Nationals of Billy Hamilton and Fred Tenney. From his extraordinary mother, Caroline Roberts, he received an enthusiasm for life that never waned, judging from the tone of his autobiography, which is written in a self-mocking tone flavored with an optimistic outlook for life.

Tunis did go to Harvard, graduating with the class of 1911 and passing through his collegiate career with Conrad Aiken, Heywood Broun, and Robert Benchley. But he was an indifferent student and preferred athletics, especially tennis, to study.

Unlike the traditional picture of a Harvard education opening doors for success, Tunis pounded the pavements before finding a job as a manual worker in a Massachusetts cotton mill, making 12½ cents an hour. With the arrival of World War I and a new bride happening simultaneously, Tunis debarked for Europe and began a close association with France. After his separation from the Army he began his writing career from a lack of other prospects and wrote for the New Yorker and New York Post while stubbornly continuing to freelance articles during the Golden Age of Sport. Tunis quickly specialized in tennis and covered the Davis Cup for many years, wrote a novel about women’s tennis which sold quite well and even had it adapted for the movie Hard, Fast and Beautiful. During the Depression Tunis kept his head above water with his wits and pen.

In the late 1930s his first juvenile novel, The Iron Duke, dealt with a Midwestern boy who comes East and gets lost in the world of Harvard. Not originally planning a juvenile book, Tunis had to be convinced that its appeal would be to young readers, but The Iron Duke continues to be a well-read story and it launched a second career for Tunis as a novelist for young people. After a sequel which took Jim Wellington through the 1936 Berlin Olympics, Tunis tried his hand at baseball fiction:

The next morning I piled in to see Mrs. Hamilton, my editor at Harcourt, Brace. Would she, I asked, be interested in a big league baseball story? Again good fortune intervened. She must have been one of the few junior book editors in New York, and surely the only Phi Beta Kappa from Vassar, who had regular seats behind the plate at the Polo Grounds each week. She nodded to my question, immediately agreed on an advance of $200, with which I hoped to pay my own way south to the baseball training camps in Florida. Without hesitation she gave me that vote of confidence every writer needs at such a moment.

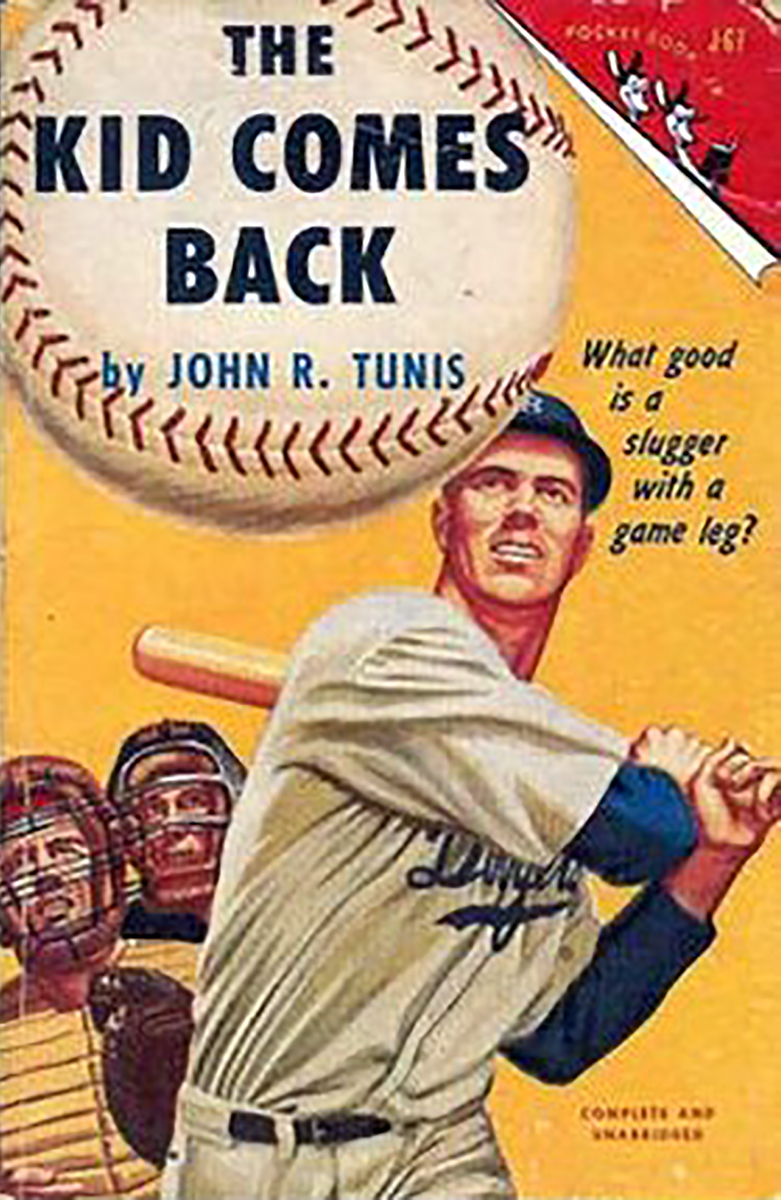

Of Tunis’s nine baseball novels, eight center on the fictional Brooklyn Dodgers, including the Roy Tucker trilogy, The Kid From Tomkinsville, World Series, and The Kid Comes Back. The ninth, Buddy and the Old Pro, follows baseball from the other end of the spectrum, junior high school baseball in the Midwest. Tunis’s Dodger books are fiction, but fiction based to a great degree on fact (the preface to TKFT reads “The author wishes to state that all characters were drawn from real life”) and it is part of the charm to a ball fan today to match a character to his real life contemporary.

This narrow line between truth and imagination helps contribute to the appeal of the series, especially to young boys whose idea of the major leagues does not include profanity, agreeable women, or long nights on the road. The 40’s and 50’s were a simpler time, but not as simple as Tunis implies. The idea of creating fiction using real teams and ball parks, and even using an occasional real-life figure (Connie Mack and Al Schacht come to mind) enables the reader to familiarize the setting of many of the events with an understanding gleaned from other accounts of the game. Descriptions of Braves Field, Crosley Field, the Polo Grounds, and even minor-league parks in Nashville and Augusta, give the Tunis books a verisimilitude which other authors lacked.

Although The Kid From Tomkinsville was not his first book for youngsters, it was his first baseball novel and the longest, fullest of his attempts to explore the inside world of major-league ball. Roy Tucker, Tunis’s penultimate hero, is a Roy Hobbs without flaws and the namesake character. We follow him from his Connecticut hometown to Florida on the day coach, a rookie pitcher in awe of his surroundings.

Tunis wisely starts off the novel with Tucker’s departure from the Tomkinsville railroad station, embarrassed by the community’s turning out to honor its star athlete while the train’s passengers gawk and smirk. (If you imagine Jimmy Stewart in the Tucker role throughout his career, you’ll be close.) At the same time Tunis picks up the communal thread of other ballplayers heading to Florida. Some are confident stars roaring down South in their roadsters; others are fading reserve catchers with families, just trying to hang on for another year. Their attraction for the game and its tenuous hold on the players is the string which pulls them south every spring. Tunis started his research with a spring training in Clearwater, so his account of practices, hotel life, and the general bonhomie of the ball club is sharply drawn.

As is typical with most juvenile fiction, Roy Tucker makes the team, pitches a no-hitter in the first night game played in Brooklyn (sound familiar?), and tears up the league the first time around. His mentor, veteran catcher Dave Leonard, steadies him through periods of doubt, catches his no-hitter, and is then released by the Dodgers as being over the hill. Horseplay in the clubhouse leads to a career-threatening elbow injury, and Roy is forced to switch to the outfield in order to stay in the game. He is attacked in his hotel room by a drunken teammate and nearly thrown out the window, an episode that is rather lightly treated by Tunis in a “boys will be boys” manner. It is one of the few episodes of player dissipation shown in his stories. Gabby Gus Spencer, the Durocher-esque Dodger manager, is killed off in a fortuitous auto accident (all done very swiftly in a page) and is replaced by Leonard, who challenges the Kid’s self-pity with his taunting phrase, “only the game fish swim upstream.” Dave Leonard is patterned after veteran Luke Sewell who befriended Tunis in Florida and served as a source of information on the details of a ballplayer’s life.

Unlike other Tunis books, TKFT takes place over a two-year period and Roy Tucker, after a year as a pitching phenom, returns to Tomkinsville to reclaim his job as night-time soda jerk and to work on his swing in the barn during the day. His second season is spent chasing down the arrogant Giants — a feat not so easily performed in 1940. Stationed in the outfield for good, Roy battles a late-season slump and saves the pennant with an extra-inning circus catch at the wall of the Polo Grounds. No one body of Tunis’s writing is as exciting as the last game of the season when player-manager Murphy is forced to eat his words “Is Brooklyn still in the league?”

TKFT captures the self-doubt and roller coaster emotions of every rookie, and changes Roy Tucker from an exceedingly naive country boy to a seasoned professional ballplayer. Yet never in his long career does Roy lose the earnestness and team spirit that characterizes his rookie season. Capturing the natural skill of Roy Hobbs with the All-American character of Jack Armstrong, Tucker is an ideal hero for a juvenile book, though the adult reader will find him a bit low on human faults.

For Tunis, ever the democrat, writing about Brooklyn and its working-class population of rabid Dodger fans was a wise decision. Throughout his books, most notably Highpockets, he expresses the sense of community shared with fan and player and the underdog mentality inherent at Ebbets Field. TKFT, while regarded as a juvenile novel, was of sufficient quality and interest that it was printed as a Victory edition paperback for soldiers during World War II. The plot is fast moving, the baseball scenes are realistic, and Roy Tucker is just the patriotic, aw-shucks hero who would appeal to Americans of all ages during the war. Realistically illustrated with charcoals by Jay Hyde Barnum, TKFT is still an engaging read nearly half a century after its publication.

The immediate sequel to TKFT, World Series (1941) is somewhat of a letdown from the excellence of The Kid. The Dodgers’ Series opponent mysteriously changes from the Yankees (at the end of TKFT) to Cleveland, and the corresponding loss of excitement is evident. The Indians were inserted solely to provide a train ride out and back and to introduce a Bob Feller-like flame thrower who beans the Kid in the first game. The Dodgers fight back to victory from a 1-3 deficit, engage in a brawl after another brushback incident, and capture the Series in seven, but the excitement is less riveting than the drama of the regular season.

Tunis realizes that the months-long tension of the pennant chase is eradicated from the two-week glitz of the Fall Classic. More of the excitement in World Series is off the field — a raucous party for the Dodgers when they are on the verge of defeat, a municipal dinner which turns into a Gashouse Gang stunt wherein ballplayers dressed up like painters manage to douse the pompous Dodger owner with whitewash, and the lure of easy money for endorsements and radio shows — but the soul of the novel lacks the intensity of its predecessor. The winning home run is hit by a nondescript teammate, and Roy’s only act of note is his slugging an obstreperous sportswriter who has called him washed up. Despite a long series of Dodger successes in subsequent volumes, this is the only one to deal with the World Series, and it does so in a way that suggests that its hoopla is more than the event itself.

The third Dodger novel Keystone Kids (1943) is perhaps the most interesting of all the baseball series, for it is more than a sports story. Written during the height of World War II, it is a combination of sports and democracy in action and emphasizes the American way of life through teamwork and a multi-national coalescing. The slumping Dodgers are revived by the arrival of the Russell brothers, up from Nashville to take over at short and second. Both make good, and Spike Russell’s leadership abilities are recognized when he is named player-manager of the team. (Did Lou Boudreau have a brother?) For the rest of the series Spike Russell ran the Dodgers firmly, with the sense of an active player.

Complicating the rookie manager’s problems is the arrival of rookie catcher Jocko Klein from the minors. He quickly becomes the target of anti-Semitic remarks from opposing bench jockeys and from his teammates who accept his quiet manner for cowardice. Spike Russell’s attempts to rally the team behind the catcher are met with indifference and resistance from his younger brother Bob who contends that all Jews are yellow, and that Klein should be abandoned to fight his own battles. Finally, in a showdown with outfielder Karl Case, Klein stands his ground:

“Get outa the way, you kike you; get outa the way and let a man hit who can.”

The rookie tottered, stumbled, then found his feet. Old Fat Stuff in the box stood watching; the crowd around the batting cage came alive. Everyone realized something was going to break at last. It did. The boy reacted quickly. He grabbed the nearest bat and, turning, was at the plate in three strides.

“Look, Case.” He waved the club at the astonished fielder.

“That stuff’s over. I’m the catcher of the Dodgers, get it? If you wanna slug it out, OK.”

Case hesitated. He started to lay on with his bat, to go for this fresh busher, when his eyes rested on Klein’s hands. They were white and tense around the handle of his club; they looked as if they meant business. The big chap looked down at the stocky figure across the plate, at those hands tightening around the handle. What he saw, he didn’t care for. He shrugged his shoulders. “O.K.,” he murmured casually. “O.K., pal.” Then he moved away.

Klein battles his way back to acceptance, until his teammates go into the stands in Philadelphia to fight for him, against a group of redneck fans. In a remarkable passage, Tunis defines teamwork by showing how each member of the team was descended from people who settled America and came together to better their families.

These were some of the things Spike did not know about his team, the team that was lost and found itself. For now they were a team, all of them. Thin and not so thin, tall and short, strong and not so strong, solemn and excitable, Calvinist and Covenanter, Catholic and Lutheran, Puritan and Jew, these were the elements that, fighting, clashing and jarring at first, then slowing mixing, blending, refining, made up a team. Made up America.

…. Gosh yes. Spike had forgotten about Chiselbeak. Old Chisel, the man no one ever saw, who took your dirty clothes and handed out clean towels and cokes, and packed the trunks and kept the keys to the safe and did the thousands of things no one ever saw. Chisel was part of the team, too; and, though Spike didn’t realize it as he followed his team along the concrete runway, part of America also. He was the millions and millions who have never had their names in the line-up, who never play before the crowd, who never hit home runs and get the fans’ applause; who work all over the United States, underpaid, unknown, unrewarded. The Chiselbeaks are part of the team, too.

In a very entertaining and thought-provoking way, Tunis explores the reasons why the country is at war and the dangers of one’s self-interest overcoming that of the common good. The spectre of anti-Semitism in the major leagues was as far as Tunis would go, although at the same time, his juvenile novels All-American, A City for Lincoln, and Yea, Wildcats!, all set at the high school level, deal with racial segregation and Negro athletes not being able to compete with whites.

Basketball coach Don Henderson, in Yea, Wildcats!, stands down an Indiana lynch mob on the courthouse steps, and shames the ringleaders by comparing the town to the integrated high school team which had worked together for a common purpose. Tunis’s failure to go further than dealing with Jews in baseball was typical of the period, in which Negroes playing professional baseball were verboten, though they were allowed to compete in high school and college sports.

Given Tunis’s proven democratic and egalitarian tendencies, it would have been very interesting if Keystone Kids could have been extended farther in its stridency; but also, given the time, the book was a refreshing revelation for the general tenor of the time. Aimed at an impressionable audience, it went far in showing how prejudice could hinder all manner of collective effort. Keystone Kids won the 1943 Child Study Children’s Book Award for breaking ground with its subject matter for that age group.

Rookie of the Year (1944) continues the Dodger season after Keystone Kids and follows Spike Russell’s team towards a final showdown with the Cardinals. Jocko Klein’s troubles are referred to in passing, but the catcher is by now an accepted part of the team and his hustling brand of ball makes him a favorite in Brooklyn. Karl Case has been traded to the Braves, eliminating his aging bat and his prejudice from Flatbush and the problem at hand is with rookie pitcher Bones Hathaway. Hathaway’s fondness for John Barleycorn is not as pronounced as with other Tunis characters on the Dodgers (see Raz Nugent in Young Razzle) but he and his roommate become pawns in a power struggle between Russell and business manager/traveling secretary Bill Hanson, who resents the young skipper as a Johnny-come-lately. Hanson is a traditional front-office type – glib, brash, and full of baseball tales from days gone by – and is not above sabotaging Dodger morale and success on the field to ingratiate himself with owner Jack McManus. The fact that Hanson is a sideline troublemaker is compared to that of a non-combatant in wartime, a sensitive point in 1944. Spike Russell, as player-manager, can be seen to have shouldered both of the roles of general and foot soldier. Misunderstandings and false accusations abound until Hanson’s perfidy is discovered, and Hathaway returns from suspension to walk on the field in the midst of a game to save the team.

It was very difficult to top Keystone Kids, and ROTY is among the weakest of the Tunis stories. Certain aspects of wartime America are evident, but the traitorous Hanson is atypical of Tunis’s Dodger organization. Hanson is eventually thrown out of baseball by McManus and evidently becomes a publicity man for the Roller Derby or a New Jersey politician.

The Kid Comes Back (1946) returns to the story of Roy Tucker, and carries him from a bomber crash over occupied France to a German prison train to America and Ebbets Field. It is a war story and a baseball story, and expresses through Tucker the uncertainty of the returning veteran.

The conflict in The Kid Comes Back lies within Tucker himself and uncertainties about his health (a back problem from the plane crash) and his value to the team at a new position, third base, contrast the differences between personal satisfaction and the value of the team as a whole. While it does not replace Mackinlay Kantor’s Glory For Me as the best fiction piece about World War II returnees, it does provide a war yam and a baseball story for young readers and a good deal more for those somewhat older.

Highpockets (1947) is a tall, gangling rookie from North Carolina. Cecil McDade is a great hitter, indifferent fielder, and self-centered individualist more concerned with his average and personal success than the team’s. Among the first of his post-war breed, McDade causes resentment among the rest of the Dodgers. Contrasted to McDade is Roy Tucker who is injured (again) in making a wall-crashing catch. Highpockets’ self-concern is shaken only when he runs over a Brooklyn boy in his new car after Cecil McDade Day.

The victim, Dean Kennedy, is unusual for his age; he’s a Brooklyn boy who is uninterested in baseball, preferring his stamp collection instead. To him Cecil McDade is no hero, just an inconvenient adult who has put him in the hospital. Faced with indifference, Highpockets’ struggle to win the boy’s friendship and to realize the value of teamwork is the core of the novel. Tunis’s ability to present baseball as a unifying thread throughout New York is evident from the passage reflecting the progress of the big game:

In the taverns all over town, in Manhattan and the Bronx, and of course in Queens, crowds hung around the television sets, watched Spike Russell have a field day at short, saw Highpockets’ tight face when he came to bat, and big Jim Duveen, pitching the game of his life, mow down the Brooklyn sluggers. On the streets, strangers spoke to strangers as they never do in New York, and everybody asked the same thing, “Anybody scored yet?” All afternoon white-coated soda jerkers came out of comer drugstores and posted up goose eggs on the sheet stuck to the front window pane. Folks sat in taxis long after they paid the bill, because for once drivers were content to sit and listen too, and manage the Dodgers for a change. Around the parked cars by the curb, little knots of people bent forward in silence, nodding as the Brooks pulled themselves out of hole after hole, inning after inning. Truck drivers even made peace with their enemies, the traffic cops, hurling the latest score at them as they turned into the main avenues of town.

Highpockets was written during the high-water mark of New York City baseball; this passage expresses the communal sense of the game’s ritual before television fragmented the audience. Interposing the ballplayer with the stamp collector, Tunis points out that not everyone is interested in the national pastime, and this makes Highpockets a better story. Interestingly, McDade himself is virtually neglected in subsequent Dodger novels; he had served his purpose and was then discarded by Tunis as an uninteresting character.

Young Razzle (1949) is a singular book in the continuity of the Dodger series, but it is not an especially good job by Tunis and is an uninteresting read. It is not a book strictly about the Dodgers. Much of the plot takes place in the minor leagues. The protagonist of the novel is not a Dodger, but a New York Yankee rookie. And the Dodgers blow a 3-1 lead in the World Series and lose in the bottom of the ninth. Not only that, Young Razzle has a slap-dash quality to it that indicates a novel written in haste. An extra-inning pennant-winning game with the Giants is dismissed with a few pages, and the seven-game World Series is condensed into 50 pages. (It rated 300 in World Series.)

The problem with YR is that Tunis splits the attention of the book between a father and son; one on the way up, the other hanging on one final year. Joe Nugent is bitterly resentful of his father for abandoning him and his mother over the course of his career. Raz Nugent is a Kirby Higbe type character — very much his own man and unencumbered by discipline or training rules. His colorful antics don’t make up for his mediocre pitching, and his inability to control his drinking and his temper push him into the minor leagues, where he faces his son on the field for the first time. Despite his faults Raz appears very proud of Joe and rejoices in his promotion to the Yankees. When Raz is recalled by the Brooks he applies himself, loses weight, and becomes a useful pitcher. Joe, on his side, gradually appreciates his father’s courage and skill, and a final reconciliation occurs at the seventh game’s conclusion.

With some thoughtful writing, this might have made a passable, if somewhat farfetched tale. (What if Phil Niekro had a son … ?) But what develops is a typical boy’s story of the period, unremarkable from any other author’s, using the interesting characters from the Tomkinsville trilogy and Keystone Kids as mere background fillers. If the rest of Tunis’s writing were like this, there would be no need to write articles examining his quality.

By 1958 when the last Dodger book was published, both baseball and the Dodgers had undergone changes. Tunis was pressed to catch up with them and it shows in Schoolboy Johnson. The most obvious baseball fact about the Dodgers in 1958 was that they were no longer in Brooklyn — instead trying to hit high flies to left 3,000 miles away. Much of the Dodger appeal lay in their location, and Tunis bravely sets his story back in Flatbush, despite facts to the contrary. This in itself was not calculated to win a large readership among boys to whom being up-to-date is more important than tradition. The plot for Schoolboy Johnson is centered around a young headstrong pitcher who loses his cool in tight situations. It is unremarkable and no better than those offered by Tunis’s competition in the juvenile fiction race. What is remarkable (surrealistic, perhaps) is the Roy Tucker character and his passage through time.

From 1940 to 1958, with time out for war duty, is a long time for a fleet center fielder, even Roy Tucker. In fact, at the beginning of SJ, Tucker is released, an over-the-hill veteran who winds up playing third base in the Sally League — a counterpoint to the schoolboy who has his career ahead of him. Through a chance set of injuries, Roy is re-signed by the Brooks, and at age 40, returns to dazzle the National League with his speed and ability. In one sequence he confuses the Braves (Tunis does have them in Milwaukee), getting the winning run across by running wild on the bases (shades of Davey Lopes).

It is evident that all of Tucker’s skills and charm are still there, so why was he released? The ultimate team player would have been offered one of those “jobs in the organization” which are always given to loyal sorts who keep their nose clean. Even stranger is the romantic subplot between the schoolboy and Maxine Tucker, Roy’s daughter, who has never been mentioned in any previous novel. If Maxine is a store decorator with an established career, she must be in her early twenties, yet neither child nor mother appears in a careful reading of the other Kid novels, and judging from Roy’s apple pie and milk character, he has been a bachelor throughout his long career.

Just why Tunis felt the need to include this mystery character is puzzling, for no explanation is made about death or divorce. Roy and Maxine live together, but the questions about the Tucker girl and the setting make the novel very disquieting for a fan of the baseball stories and perhaps it was a fitting way for Tunis to end his series. With the Dodgers moved from Brooklyn, and with Roy Tucker’s past catching up with him, there was nothing more to write.1

The one non-Dodger baseball story, Buddy and the Old Pro (1955) takes place on the sandlots of a Midwestern town and is one of Tunis’s very best works. Buddy Reitmayer, shortstop and captain of the Benjamin Franklin school team, lives and breathes baseball as does his hero, Mr. McBride, a former major league star cut from the Ty Cobb mold. When McBride moves to Petersburg and gets a coaching job to augment his work as a night watchman, the conflict between playing clean baseball and winning at all costs is presented. What a star major leaguer is doing at a menial job and coaching a school team is not explained satisfactorily, nor is it clear why there is no adult coaching Buddy’s team, but here as in no other Tunis story is the conflict between good and evil so well defined.

McBride’s team intimidates the Franklin boys with beanballs, bench jockeying and sliding in with spikes high, and the volunteer umpire is no match for the gamesmanship of the ex-big-league terror. Buddy’s team, in sneakers and ragtag uniforms, is not able to fight back. When Buddy takes a third strike with the bases loaded to end the game, he throws a temper tantrum that rivals McBride’s best, embarrasses his parents, and reflects the doubts he has about the way to play the game. There are nice touches Tunis interjects, such as the closing of the Franklin school at the end of the year (and its consolidation as Curtis P. Gerstenslager Jr. High), and the inability of adults to take the boys’ problems seriously. The local sports editor is seen as absent-minded and ineffectual, and only Buddy’s father is able to appreciate the injustices of matching boys against a major leaguer, and the wisdom of playing by the rules vs. the winning at-all-cost approach.

As Tunis was in his mid-60s when he wrote BATOP, he shows a remarkable appreciation of what it is like to be 12 and playing ball for keeps. Significantly he places the setting away from a Little League, and one can believe that he feels that boys should be allowed to play and have fun on their own — not a novel idea even in 1955 but one which bears repeating. Even at the school level many of the tensions and situations of the game are identical to those of the major leaguers and BATOP is not noticeably different from the Dodger books in game description. Buddy Reitmayer’s taking a third strike is part of a boy’s growing up, and if he is unable to be considered a prospect by the major leagues (as he feels on the way home), he is able to grow up a wiser individual, not as apt to accept the infallibility of his heroes.

In The Other Side of the Fence (1953), a non-baseball novel, Tunis takes the unusual step of making his protagonist a comfortable Connecticut teenager who is bound for Yale. Setting out on a cross-country trip with an unreliable friend, Robin Longe decides to set out on his own and hitchhike his way across America. Using his wits and golfing ability to catch rides and provide odd jobs, he meets a variety of people and sees both good and bad sides of America. Tunis’s skills describing scenery and regional distinctions are well used, and the historical setting of Connecticut suburban life in the Eisenhower era provides us with an unlikely underdog, the preppie naive traveler. Sport is taken as the great common denominator, as everyone from truck drivers to teenagers to businessmen are bound together from a mutual love of the game. Robin’s acceptance in California is sealed by his athletic skill, and his desire to succeed in individual sports is shown to be related to his desire to make it across the country on his own. TOSOF is not readily found these days, but it is well worth the search.

After Schoolboy Johnson Tunis continued to write juvenile fiction. His book His Enemy, His Friend (1967) written when he was 77 and set in the familiar location of France, was a savage indictment of war and its long-term effect on countries and people. It was obviously his personal statement on Viet Nam. Again, the subjugation of individual glory for the sake of the common good is seen as man’s ultimate goal.

John R. Tunis died in his beloved Connecticut in 1975. He had written over 30 books and more than 2,000 magazine articles, mostly on sport, and had seen Babe Ruth replaced by Reggie Jackson as the nation’s sports hero — both Yankee right fielders who could hit home runs. Throughout his 50-year career he had observed the role that sports played in building the character of adolescents in America and had attempted to better his audience by his stories, which glorified self-sacrifice, team spirit, and the ability to improve oneself through hard work.

The opening words of A Measure of Independence puts it best. “I am the product of a parson and a teacher. Any such person is forever trying to reform or to educate, himself if nobody else.” Tunis attempted to identify that which is beneficial about sport and character by using the most popular sport of his day — baseball — as the vehicle. That his works are still read and enjoyed today reflects the skill of his writing and the aptness of his lesson.

Notes

(For those persons who grew up with Roy Tucker and the Dodgers it must be rewarding to consider that Roy’s number 34 was never retired, and was worn with distinction by Fernando Valenzuela.)

1 Interestingly enough, Karl Case shows up again in Schoolboy Johnson (1958), again playing the outfield for the Dodgers. Instead of being in his dotage, he is described as a hustling veteran with a strong arm. His politics have changed during his exile, as he is shown in an extremely sympathetic light. Unlike his earlier appearances where he is described as figuring his batting average as he runs down to first base, the elder Case is a team player like Roy Tucker. Evidently playing the outfield makes one younger and more liberal. Jocko Klein, in SJ, has been released and is managing Birmingham.