San Jose Asahi’s 1925 Tour of Japan and Korea

This article was written by Ralph M. Pearce

This article was published in Nichibei Yakyu: US Tours of Japan, 1907-1958

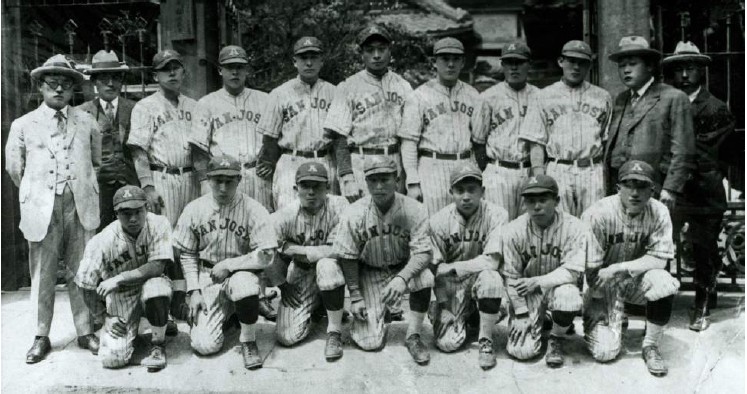

The Asahi in Osaka, Japan, during their 1925 tour. From left, back row: Kichitaro Okagaki, Nobukichi Ishikawa, Jay Nishida, Morio Sera, Harry Hashimoto, Jimmy Araki, Earl Tanbara, Mr. Takeshita, Fred Koba, and two Japanese officials. Front row: Tom Sakamoto, Sai Towata, Jimmie Yoshida, Jiggs Yamada, Frank Ito, Russell Hinaga, Ed Higashi. (Kanemoto Collection, Kifune Family Album).

The San Jose Asahi Baseball Club was one of a number of Japanese teams to organize in Northern California between 1903 and 1915. Other cities to organize early teams included San Francisco, Oakland, Alameda, and Florin. The name Asahi means Morning Sun in Japanese and was a popular team name. San Jose’s first Asahi team was made up of Issei (first-generation immigrants) players and lasted only a few years. In 1918 one of the former Issei players encouraged a young Nisei (second-generation) fellow, Jiggs Yamada, to reconstitute the team with Nisei players. Jiggs, a catcher, enlisted the assistance of 15-year-old pitcher Russell Hinaga, and the two soon put a team together.

Unlike the Issei players, these young Nisei players were bom in the United States and had attended English-language schools with a largely Caucasian enrollment. Because of this, both a generational and cultural gap existed between the Issei and Nisei. Through the shared love of baseball, Nisei teams like the San Jose Asahi helped bridge this divide. In the early 1920s, a sympathetic newspaper columnist in San Jose, Jack Graham, encouraged the Asahi to extend that bridge by participating in games outside the Japanese leagues. This participation drew the larger San Jose community to the Asahi Diamond in Japantown, and there Caucasians began to mingle with Japanese Americans, helping to establish familiarity and friendship.

Another bridge in the making was the growing baseball friendship between the United States and Japan. Japan’s enthusiasm for the game had been spreading since its introduction in the 1870s. The tradition of international baseball exchanges began with Waseda University’s 1905 tour of the American West Coast and continues to this day. This friendship through the two nations’ shared love of baseball helped foster cultural appreciation and understanding.

San Jose’s opportunity to visit Japan came in 1925 at the invitation of Meiji University, whose baseball club had toured the United States the year before. The timing couldn’t have been better for the Asahi; several of the players—Jiggs Yamada, Morio “Duke” Sera, Fred Koba, and Earl Tanbara—were anticipating retirement from the team. It was agreed that they would stay with the Asahi until their return from Japan.

It is believed that Meiji University provided some funds for tour expenses, though much of the burden was on the team and its Issei supporters. The first obstacle was the cost of transporting 17 passengers to and from Japan. Jiggs Yamada explained how this was accomplished:

Well first, we had to get some way to go to Japan. A boat was the only thing we could get. We happened to have a boy, Earl Tanbara. … Tanbara’s folks, mother and father, worked for the Dollar Steamship Company family in Piedmont. So when he graduated high school, we had his father talk to Mr. Dollar and ask him if he could do us a favor. He said, “Sure, as soon as Earl [goes] to Cal [Berkeley] and graduated, he’s got to work for me at the steamship company.” They were going to open up an agent in India. So he said, “Sure, if he promises to do that, I can have him going on our boat to Japan.” .. .So that’s how we got to go to Japan on a boat. People figured it was funny how we got to go to Japan . because at that time the steamship boat was expensive.1

A few days before departure, Asahi supporter Seijiro Horio gave $800 to Nobukichi Ishikawa, the team’s treasurer. This appears to have been the primary funding source for the team’s trip.

Jack Graham publicized the coming tour to Japan in a number of articles. On March 18, 1925, the day before the team departed, he wrote: “There will be a big delegation of fans in attendance and a bumper crowd of Japanese fans will be on hand to see their favorite sons in their final game in this city. The Asahi team will sail on Saturday for Japan, where they will play a series of games in the flowery kingdom. On their return, they will stop in the Hawaiian Islands, where they will play seven or more games. It will be the latter part of June before they return. The Asahi team has made many friends in this city by their gentlemanly manner in playing the national game, and whenever they stage a game here there is always sure to be a big turn-out.”2

The next day, Graham ran a column praising the Asahi and encouraging local pride in the team as representatives of San Jose. A large photograph of the team ran at the top of the sports section, remarkable in that images of local teams rarely appeared in either American or Japanese American papers at the time. The caption read in part: “The Japanese Asahi baseball team will leave San Jose on the first leg of its joumey to the land of cherry blossoms this morning, when it takes the train to San Francisco where it will stay until Saturday, when it will embark on the President Cleveland for Japan.”3

The team members making the trip to Japan were pitchers Jimmy Araki and Russell Hinaga; catchers Ed Higashi and Jiggs Yamada; first baseman Harry Hashimoto; second baseman Tom Sakamoto; third baseman Morio “Duke” Sera; shortstop Fred Koba; third baseman-outfielder Sai “Cy” Towata; outfielders Frank Takeshita, Frank Ito, and Earl Tanbara; and utility players Jitney Nishida and Jimmie Yoshida. While the team was in Japan, the strong Asahi “B” team continued to play in San Jose against teams of its caliber. Asahi Diamond was also made available for use by other local teams and management of the diamond was temporarily turned over to locals Happy Luke Williams and Chet Maher.

The Asahi, along with the trip’s manager, Kichitaro Okagaki, and its treasurer, Nobukichi Ishikawa, left San Francisco on March 21, 1925, and a little over two weeks later they arrived in Japan, giving them about a week to recover before their first game. When the team arrived in Japan, Earl Tanbara purchased two Mizuno baseball scorebooks. Earl kept meticulous track of each game, including dates, locations, and the names of all the players.

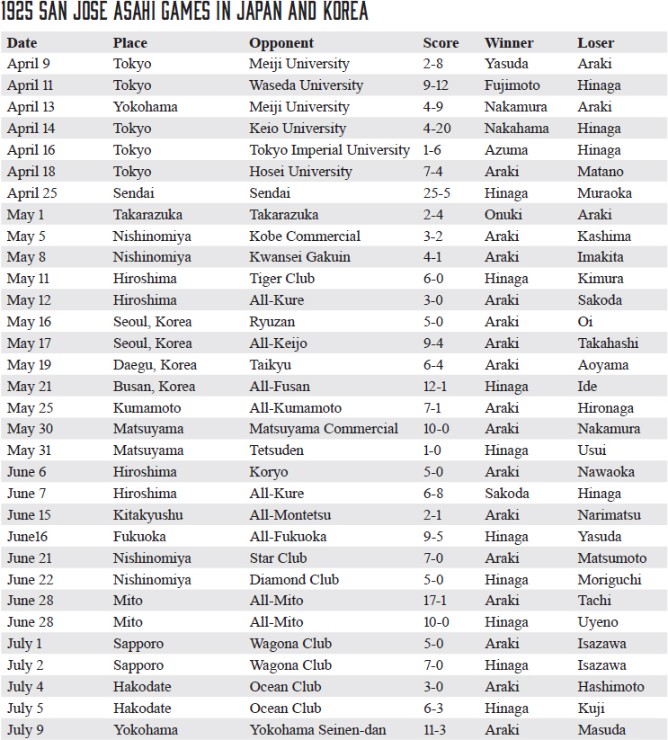

The Asahi played their first game on Thursday, April 9, against their hosts Meiji University. They lost 8-2 with Araki going the distance on the Meiji grounds. The Asahi played their second game on Saturday, April 11, against Waseda University. They were playing better now, though they lost in a 12-9 slugfest. Russ Hinaga and Jimmy Araki shared the pitching chores, Frank Ito got a double, Harry Hashimoto had a triple, and Cy Towata and Earl Tanbara hit home runs. Each side recorded only one error.

The Asahi played their third game two days later with a rematch against their hosts, Meiji University. Jimmy Araki again pitched the entire game with Ed Higashi doing the catching. Araki was knocked around for a 9-4 loss, despite a batch of errors by Meiji. Next up—the very next day—was Keio University, another tough team. If the Asahi were ready for a win, it would have to wait for another day. Araki and Hinaga pitched the team to a 20-4 shellacking, the Asahi racking up seven errors along the way.

Two days later, on April 16, the Asahi faced Tokyo Imperial University. Once again Araki and Hinaga teamed up. The team was sharper that day, making only one error. Harry Hashimoto hit two doubles, chalking up a run. That was the Asahi’s only run, though, to six for Tokyo and their fifth loss in five games. The Asahi played for the love of the game, but they were serious competitors and this situation was not acceptable. Jiggs Yamada explained the problem and the remedy:

We didn’t play so good because our legs were shaking and all that and the ball was different. It was a regular size American ball, but the cowhide, it slips. The pitcher couldn’t play, pitch curves or anything and the players themselves couldn’t throw the bases, so we couldn’t play good. So finally we told the manager [Okagaki] of our team “Get us some American balls.” So they sent us a one dozen box of American balls, then we started to play different. Then we started to play our regular play.4

Teammate Duke Sera confirmed the situation, saying that after leaving Tokyo, the manager saw to it that future Japanese teams could use their own baseballs when they were in the field, and that the Asahi players would use American balls when they were in the field.5

On April 18, the Asahi played yet another strong university nine. This time it was against Hosei. Jimmy Araki took to the mound for the Asahi and despite several errors, the team finally got its first win. The Asahi won 7-4 and scored all their runs in the first three innings, thanks in part to a home run by Araki himself. The team followed up a week later with a 25-5 victory over Sendai, with Hinaga pitching and Araki sharing left field with Tanbara. The Asahi suffered another loss on May 1, against Takarazuka before beginning a 13-game winning streak.

The Asahi had played their first six games in Tokyo against strong university teams before venturing north to Sendai. From Sendai, they headed south about 500 miles to Osaka. They played three games in the Osaka area and one game in nearby Kyoto. In the game against Kyoto Imperial University, Tom Sakamoto hit a dramatic “Sayonara Home Run” or walk-off home run in the 10th inning to win 3-2.

From Osaka, the team headed south to Hiroshima for two games. As they traveled the country by train, they continued to accumulate wins and, more importantly, became acquainted with the land of their parents.

One of the players, Duke Sera, had been bom in Hawaii, and then raised by his uncle in Hiroshima. His uncle had sent him to Stanford University to complete his education. When the team visited Hiroshima, Duke’s uncle held a reception for the team. According to Yamada, when the uncle met Duke and the team he quipped, “What the hell are you doing with this bunch here? You’re supposed to be studying!”

After the final game in Hiroshima on May 12, the Asahi traveled 400 miles back to Tokyo. It was the team’s original intention to return to the United States sometime in June. Whatever plans they may have had, however, were altered upon their return to Tokyo (except for Duke Sera, who had to return to his studies at Stanford). Jiggs shared the change of plans:

In Tokyo, there’s a letter to our manager that they want us to go to Korea, because the Korean government, the American Consulate and all that, were anxious to see us play against the Japanese there. It was a lot of fun there, because the American consuls and their families invited us to dinner the night before the game. In Keijo [now Seoul], the capital of Korea, they all came out to watch us play. When we played, first we had infield practice and batting practice and all that and you know we talk nothing but English. We don’t talk Japanese when we’re playing ball. Then this guy, this American guy says ‘Oh boy, we got an American team here, we haven’t got a Japanese team!6

The Asahi played four games in Japanese-occupied Korea (then known as Chosen) between May 16 and May 21. The first two games were played in the capital, the third game in Taikyu (now Daegu), and the final game in Fusan (now Busan). All transportation to and from Korea had been provided for by the Asahi newspaper in Japan. The games in Korea were covered by a Japanese-language newspaper, the Keijo Nichinichi. They devoted the most attention to a game that they sponsored, which was played on May 17 against the All-Keijo team. The translated article reads:

“The game between San Jose and Keijo was played at the Ryuzan Railroad grounds in the middle of the afternoon of the seventeenth day, with plate umpire Marunaka and base umpires Ishihara and Suzuki. It was a very fine day. A big crowd swarmed and got excited over the unprecedented great game. Keijo, an uprising team, won the All Korea Championship last year. On this day, pitcher Takahashi performed well for Keijo and San Jose’s Hinaga held Keijo batters in check with his breaking balls. The game went into extra innings. Finally, despite Keijo’s good efforts, San Jose batters rallied to score five runs in the 12th and Keijo lost a close game.”7

The article gives an inning-by-inning account of the game, summarizing as follows:

“The Keijo team was expected to push San Jose hard, if Takahashi pitched well. As Takahashi had few pitches, we expected that he would be rallied against at some point in the game and that Keijo would be beaten by four or five runs. In other words, San Jose’s attack was delayed to the twelfth. That was the reason Keijo luckily fought gamely into the extra innings. But it was clear that San Jose looked stronger than Keijo. … Keijo, good at overcoming pinches, played better than it was able to. … Keijo batters hit well the fastballs off breaking-baller Hinaga. San Jose was confident to win the game, but they should have brought in a new pitcher in the seventh. It was a costly error [by San Jose] that allowed Hioki to score in the ninth [tying the game]. Pitcher Takahashi pitched superbly, using breaking balls on the outside of the plate; however, he wasn’t good with a runner on. It was an unexpectedly close contest for San Jose. It proved that Keijo played well. Keijo is expected to win another Championship this year. Keijo fans in the stands were not broadminded enough to cheer for their overseas countrymen, guests from afar. The San Jose players must have felt sad. The Keijo fans, lacking understanding and moderation, jeered at the San Jose players. Keijo fans betrayed the expectations of San Jose’s players who wanted to bring back good impressions of their land and countrymen.”8

The Asahi arranged for their return trip to Tokyo to begin from the southern island of Kyushu. The team contained many players whose families were from either Kumamoto (on Kyushu) or Hiroshima, so the team’s first stop would be Kumamoto where they beat the All-Kumamoto team 7-1. Hinaga’s father had written ahead to family in Kumamoto that Russ would try to visit while in Japan. Yamada was also from Kumamoto and had written to his uncle and grandparents, whom he’d never met. Harry Hashimoto and Fred Koba were also from Kumamoto.

Jiggs Yamada told a story about arriving at one of the many stops along the way to Kumamoto. It was common for peddlers to walk along the station platform offering their wares to the passengers sitting inside the trains waiting to depart. If a passenger was interested in something, he would just open the window to make the transaction. At one stop, Jiggs and the players sitting near him could hear one of peddlers outside gradually making his way up to them calling out, “Sushi! Manju! Sushi! Manju!” When the peddler had come up even with their window, they all looked out and saw that it was Russ Hinaga! Jiggs said that this was a typical stunt for Russ, describing him as a funny, comical guy.9

The Asahi were well treated by the relatives in Kumamoto. They were honored at a reception and, according to Yamada, had a very good time. In fact, it was in Kumamoto that Jiggs met his future wife, Aki.10 From there, they traveled north to Matsuyama on the island of Shikoku. After playing two games on Shikoku, they crossed back over to the main island of Honshu to return to Hiroshima.

Two more games were played in Hiroshima. The first was a no-hitter pitched by Jimmy Araki on June 6 against Koryo, presumably a high-school team, at the Kannon Grounds. Araki started the first inning by putting the opposing batters down in order, with two strikeouts and Cy Towata throwing a batter out at first. The Asahi replied with a run to finish the inning. In the second inning, Koryo’s batters kept first baseman Harry Hashimoto busy with two batters thrown out and a fly out at first. The Asahi responded with another run before ending the inning with two fly outs. The third inning didn’t go so smoothly for the Asahi as its defense disrupted what was otherwise a perfect game. Koryo got its first runner on base on an error by third baseman Towata. Towata threw the next batter out at first, with the runner now safe at second. The following batter hit into a fielder’s choice at third. The next at-bat produced another error, this time by Fred Koba at shortstop. The error resulted in the Koryo batter making it safely to first and allowing a runner to advance to second. Araki was able to end the inning with a strikeout. The Asahi did better on offense that inning, tallying its final three runs. The rest of the game went well for San Jose, as Araki retired 18 straight batters and finished with a no-hitter. The final score was 5-0, with six strikeouts. The second game in Hiroshima was the Asahi’s seventh and final loss of the tour and ended their 13-game winning streak.

From Hiroshima, the team headed south again, back to the southern island of Kyushu. There they played two games in Fukuoka to begin an 11-game winning streak. In a game on June 15 against All-Montetsu, after each team scored a run in the first inning, neither team scored for 10 more innings. Jimmy Araki went the distance for the Asahi. Finally, in the bottom of the 11th inning, Fred Koba scored on a hit by Higashi to win the game. After beating the All-Fukuoka club on June 16, the Asahi began their trek northward.

The father of one of the players owned a railroad on the northern island of Hokkaido.11 The player made arrangements through his father for the team to play in Sapporo. On their way to Sapporo, the Asahi played two games in Osaka, then two games in Mito, about 50 miles northwest of Tokyo. Having traveled nearly the entire length of Japan from Fukuoka to Sapporo, the Asahi played two games in Sapporo on July 1 and 2. Then they went south to play two games against the Ocean Club in Hakodate. From there they left for Yokohama (just south of Tokyo) and played the final game of their tour against the Yokohama Seinendan on July 9. In the fourth inning of this game, Earl Tanbara hit the series’ only grand slam.

After the shaky start against the Tokyo-area universities, the team had collected an impressive 26 wins and 7 losses. The Asahi scored 216 runs and allowed only 104 runs. Over half of the runs allowed came in the first five games. In their winning streak of 13 games, there were three shutouts in a row and a no-hitter. In the 11-game winning streak, there were four shutouts in a row. Jimmy Araki threw seven shutouts, one of which was his no-hitter against Koryo. Russ Hinaga also did quite well with five shutouts, one of which was a three-hitter. Eight players collected a total of 17 home runs with Earl Tanbara leading the pack with five. Catcher Ed Higashi had the highest batting average, .342. Tanbara followed at .318 with 40 more at-bats.12

Asahi third baseman Duke Sera observed that the Japanese infielders were cautious and that it was fairly easy to beat the throw to first; meanwhile the Japanese outfielders were faster than they were. He mentioned that the umpires in Tokyo were particularly unfair when it came to calling strikes over the comer of the plate, which hurt curveballer Russ Hinaga. The Asahi took advantage of the fact that they could understand their opponents’ Japanese while only speaking English with each other.13

The Asahi departed Yokohama for the return voyage to the United States on July 14, and arrived home on July 29. Though this was just one of many baseball exchanges over the course of the twentieth century, the Asahis made an important contribution to an enduring friendship between two countries. It was a friendship that began on a baseball diamond, and then grew to something more; a friendship that endured even war. For the players themselves, this journey of friends to the land of their parents and forefathers left them with memories to last a lifetime.

RALPH M. PEARCE is a local history author who shares a passion for Japanese baseball history. His first book, From Asahi to Zebras: Japanese American Baseball in San Jose, California, was published in 2005. His second book, San Jose Japantown: A Journey, co-authored with Curt Fukuda, was published in 2014 by the Japanese American Museum of San Jose. In 2019 he contributed a biographical sketch to the book Gentle Black Giants: A History of Negro Leaguers in Japan by Kazoo Sayama and Bill Staples Jr. Ralph currently works in the Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Library’s California Room, the San Jose Public Library’s state and local history collection.

SOURCES

Ralph M. Pearce has adapted this chapter from his book, From Asahi to Zebras (San Jose: Japanese American Museum of San Jose, 2005).

NOTES

1 Jiggs Yamada, interview, October 23, 1993.

2 Jack Graham, “Asahi Team Will Play Portland Beavers Here Today,” San Jose Mercury Her, March 18, 1925: 22.

3 “Asahi Ball Team Leaves Today on Tour of Japan,” San Jose Mercury Herald, March 19, 1925: 18.

4 Yamada, interview.

5 >Theron Fox, “Nippon Manager Tells of Tour of Ball Outfit,” San Jose Evening News, August 3, 1925: 8.

6 Yamada, interview.

7 “Peninsula Champion Defeated by Narrow Margin,” Keijo Nichinichi, May 19, 1925: 3. Translation by Yoichi Nagata.

8 “Peninsula Champion Defeated by Narrow Margin.”

9 Yamada, interview.

10 Glenn Iida, interview, May 30, 2011.

11 Jiggs Yamada was unable to remember which player.

12 Earl K. Tanbara, San Jose Asahi Japan Tour Scorebook 1925.

13 Jack Graham, “Japanese College Seeks Ruth for Exhibition Tour,” San Jose Mercury Herald,, June 16, 1925: 18.