Sandy Koufax as a Jewish American Sports Icon

This article was written by Sarah Wexler

This article was published in Sandy Koufax book essays (2024)

Ask the average American to name a Jewish athlete. For many, the first to come to mind will be Dodgers great Sandy Koufax, even though it’s been nearly six decades since his retirement from major-league baseball.

Ask the average American to name a Jewish athlete. For many, the first to come to mind will be Dodgers great Sandy Koufax, even though it’s been nearly six decades since his retirement from major-league baseball.

Like many of his sport’s all-timers, Koufax maintains an almost mythic status–especially among Jewish baseball fans, as well as the broader Jewish American community. Early to mid-1960s baseball was in large part defined by Koufax baffling hitters with a high-octane fastball and a devastating curveball en route to becoming a first-ballot Hall of Famer. It remains one of the most dominant peaks for any pitcher.

For the purposes of this article, just as important was his fateful decision to sit out Game One of the 1965 World Series against the Minnesota Twins in recognition of Yom Kippur, the holiest day on the Jewish religious calendar.

Koufax was not the first great Jewish athlete, nor the first Jewish baseball star. Yet the legendary left-hander seems to occupy a special place in the Jewish American imagination, while non-Jewish sports fans also recognize his place as a revered representative of his people.

To understand why Koufax retains this image as a specifically Jewish superstar, the author talked with a Jewish historian, a rabbi, a fan who grew up watching Koufax pitch, and several contemporary Jewish major-league players and personnel. Their views offer insight into why Koufax’s legacy as a Jewish American sports icon has endured for so long and with such strength.

What a historian says

Signed by the Dodgers ahead of the 1955 season, Koufax played his first three seasons in his native Brooklyn before the team relocated to Los Angeles in ’58, where he truly made a name for himself. From 1961 to 1966, Koufax won three Cy Young Awards and a National League MVP Award while earning seven All-Star selections.1 He threw four no-hitters–one a year from 1962 to 1965–culminating in his perfect game against the Cubs. He was a four-time World Series champion.

Location somewhat explains Koufax’s national prominence, as he played not just in the country’s two biggest Jewish communities, but in the two largest media markets. But even more so, it was the era in which Koufax played that enabled him to build his legend–and not just because the advent of televised games afforded greater exposure than previous generations of players had.

“Koufax would have been part of this assimilating impulse of his parents’ generation, seeking to balance full allegiance and loyalty to United States and holding onto some measure of Jewish identity–particularly, Jewish religious and ethnic identity–and that piece of the puzzle was becoming smaller than the American piece,” said David Myers, distinguished professor and Sady and Ludwig Kahn Chair in Jewish History at UCLA. “It was a period in which those two dimensions of identity were being balanced and rebalanced and recalibrated.”2

Assimilation is something of a double-edged sword. It’s hard to argue against certain privileges like greater safety and opportunity, but a loss of cultural identity is difficult to reckon with. The mid-twentieth century featured a rediscovering of Jewish pride in America, in no small part due to events following Israel’s establishment.3

Compare Koufax to Hank Greenberg, the only other Jewish player enshrined in the National Baseball Hall of Fame. The son of Romanian Jewish immigrants,4 Greenberg broke into the big leagues with the Detroit Tigers for good in 1933, and he played until 1947, missing the 1942-44 seasons due to service in the US Army.5 Like Koufax, Greenberg also once sat out on Yom Kippur–but that came during a pennant chase in 1934, rather than the World Series.6

Because antisemitism in the United States was worse pre-World War II, Greenberg routinely faced anti-Jewish abuse from opposing players and fans7 in ways that Koufax didn’t (although Koufax did endure some, including from his own teammates and in the form of hate mail, as well as stereotypes in the press related to his purported intellectualism).8 But there’s no doubt it was a society more accepting of Jews overall.

“A significant tide of sympathy moves toward Jews and the Jewish experience after the Holocaust,” said Myers. “[Before World War II] there was fear, on the part of some, that Jews would assert their own collective interest and drag the United States against its will into a major global conflagration. So, there was that aura of suspicion. Whereas after the war, after the full excesses of the Holocaust became known, that sense of suspicion gave way to a greater sympathy for Jews.”

Essentially, because Jews of Greenberg’s day had even greater outsider status than Jews of Koufax’s day, his affirmations of Jewish identity didn’t register in the way Koufax’s did. In a time when Jews were more integrated into the mainstream, it was hugely impactful for Koufax to assert that Jewish religion and culture mattered and deserved respect, even when they stood in contrast with societal norms.

“It’s precisely Koufax’s act in the midst of this assimilatory era that I think lent it a particular power,” said Myers. “It may, at least for Jews, grant him a measure of immortality.”

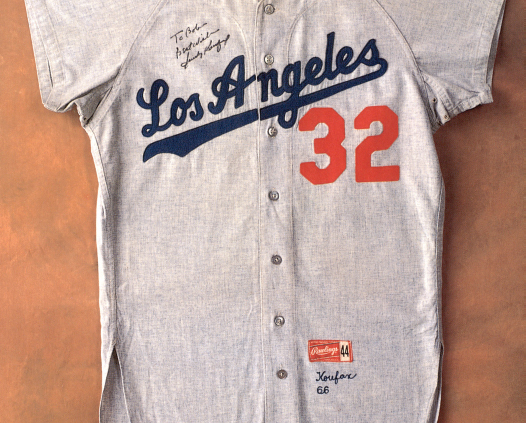

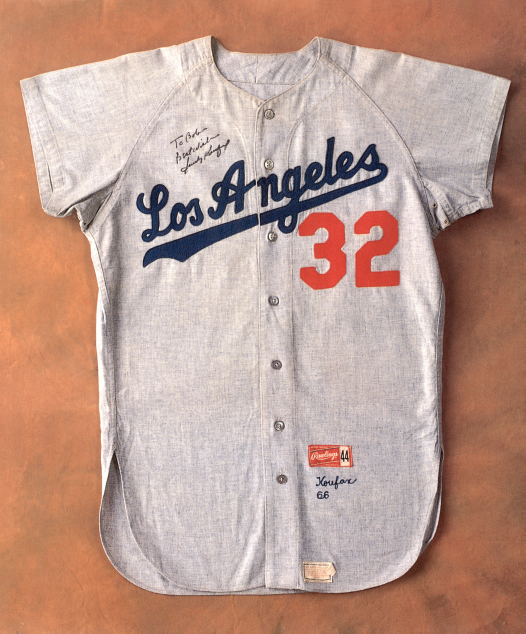

The Dodgers retired Sandy Koufax’s No. 32 jersey number in 1972. Jersey numbers for Roy Campanella (39) and Jackie Robinson (42) also were retired. (SABR-Rucker Archive)

What a rabbi says

Like Koufax, Reb Jason Van Leeuwen grew up in New York before moving to California for work. A Syracuse native, Van Leeuwen was a big baseball fan, too young to have seen Koufax pitch but certainly aware of the southpaw’s achievements–and he was excited to learn that this accomplished athlete happened to be Jewish.

The head rabbi at Temple B’nai Hayim, a Conservative synagogue in Sherman Oaks, California, Van Leeuwen has come to view Koufax as someone who holds a unique place in Jewish American history.

“Koufax, more than any other Jewish ballplayer, symbolizes the American Jew who makes it, succeeds, is at the top of his field, but does not deny and even affirms his Jewish identity–even to the point where he will observe a religious holiday in the middle of a World Series,” said Van Leeuwen. “He’s a statement that you can have it all as a Jewish American. You can stay Jewish, and you can be fully American.”9

Jewish identity, especially in the diaspora, is a multifaceted and deeply personal thing. It comprises religious, ethnic, and cultural components, each bearing significance that varies vastly among members of the community. And it is generally accepted that, while he valued his Jewish heritage, Koufax was not religiously observant. There’s even a dispute over whether he attended Yom Kippur services in October 1965, or if he simply stayed in his Twin Cities hotel room.10

Asked whether it mattered where Koufax was that day, Van Leeuwen said the act of Koufax prioritizing culture over sport is bigger than any of the smaller details when it comes to his place in Jewish American lore.

“If you ask people what do they know about Koufax: a great pitcher, four no-hitters, didn’t pitch on Yom Kippur in the World Series,” said Van Leeuwen. “Beyond that, the average Jewish American can’t say much else about him.”

What a fan says

The Dodgers weren’t the only ones who moved to Los Angeles in 1958. That’s also when Jim Gilson, then 6 years old, relocated there from Cleveland along with his family. Several times a season, he made the trip from LA’s west side to go to games. For their first four years in town, that was at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum, where Gilson enjoyed seeing Wally Moon hit his famed “Moon Shots” over the short left-field porch. Then, in 1962, Dodger Stadium opened its gates.

Gilson recalls the thrills of Maury Wills’ daring efforts on the basepaths, and the intimidating persona of Koufax’s co-ace, Don Drysdale. But to a young Jewish child, it was Koufax himself who stood out most, with Gilson estimating he attended as many as 10 of the southpaw’s starts.

“He had a commanding presence that went beyond his baseball prowess,” said Gilson, a retired lawyer and museum executive. “Even to a kid, he appeared to carry himself with supreme confidence. … I have a memory of feeling like he’s a master, he knows he’s a master, [but] he’s not outwardly puffing out his chest about that.”11

There was a time in the United States when baseball was regarded as a tool for outsiders to gain acceptance,12 which was true to Gilson’s experience. He made friends playing Little League, and a shared passion for the new hometown major-league team was a natural way to fit in with his adopted community. In a more personal sense, Koufax’s Jewishness, paired with his unquestioned greatness, made him not just an icon to Gilson and others, but a trailblazer as well.

“You could point to Sandy Koufax as a reason to be accepted,” said Gilson. “… Sandy Koufax being accepted and extolled, I think, was part of what made me feel like I can be accepted and maybe even extolled.”

Also contributing to Koufax’s mystique: his reputation for keeping a low profile and valuing privacy, making his occasional public appearances at Dodgers spring training, Hall of Fame ceremonies, and big games all the more exciting.

“He retains both that reserve and impeccable public performance,” said Gilson. “And man, he looks like he could pick up the ball and still strike out 18 guys. … And he still looks like a star. He has movie-star looks, and I don’t think that hurts, either.”

What players say

Sports fandom usually runs through families, with an oral history component of parents telling children about stars of their youth. That was the case for Astros second baseman Alex Bregman, whose family admired the Dodgers pitcher so much they even named their dog Koufax.

When Bregman learned about Koufax from his father and his grandfather, Jewishness was regularly part of the discussion.

“Sandy Koufax is always the guy,” said Bregman. “I think it’s just passed on from generation to generation. I’ll teach my son about Sandy Koufax as well.”13

The complex nature of Jewish identity makes it hard to pinpoint just how many Jewish players there have been throughout major-league baseball history. But it is pretty widely agreed that, at least on the athletic side, Jews have been underrepresented in both baseball and sports as a whole.14

That’s a big reason why so many Jewish major-league players have long looked up to Koufax–there haven’t been many others to look up to, certainly not those who could be argued as the best at their position. Take Braves left-hander Max Fried, an LA native who modeled his own curveball on Koufax’s15–despite the fact that even Fried’s father was too young to have watched Koufax.

As much as broader midcentury American society shaped Koufax’s story, some baseball-specific aspects factor in as well. For one thing, 1960s sports medicine was not advanced enough to keep Koufax healthy, and he spent his last few seasons dealing with extreme arm pain and swelling. Doctors suggested that he risked losing the use of a limb or finger amputation if he continued, leading Koufax to retire at just 30 years old.16 As much as Koufax’s statistics explain why he is admired, those years he didn’t get to play also contribute to the baseball world’s fascination.

“There’s a little bit of like, ‘what could have been,’” said Fried. “… He was so good for a really good amount of time, and he had to pretty much retire in the middle of his prime. … That leaves a lasting impact. Most people, you see [them have] a little bit of decline, but for him, it still feels like he was on an ascent.”

The baseball calendar has also changed substantially. The postseason has expanded from just the World Series to several rounds. It now takes a few weeks of playoff games to reach the fall classic, which comes in late October. Although the High Holy Days move each year on the Gregorian calendar, they almost always occur in late September or early October, with October 14 being the latest date that Yom Kippur can fall.17 So unless the major-league schedule or the postseason format shifts drastically again, no player will get to make an impact statement like Koufax in 1965.18

But that decision still speaks volumes to Jewish players, even those who don’t make the same choice for themselves.

“The biggest [act] that made him a legend was the ability to put his faith before baseball and sit out on Yom Kippur,” said Fried. “[The World Series was] something that is obviously a big deal and a lot of people really care about, but … for him to be able to take that and sacrifice maybe what would be a [championship] to respect his religion, it just shows the kind of person and the man he is.”

Beyond his sporting skill, Koufax has proven to be a role model for subsequent generations of major leaguers, Jewish and not, when it comes to how to conduct oneself.

“[Koufax] just [rises] in stature and impressiveness when you meet him, because he’s such a thoughtful, gentle, normal dude,” said Gabe Kapler, then manager of the Giants. “That’s what really stands out, is just what a good person he is, and a guy who just doesn’t [care] about the spotlight. I don’t really think he cares if he is recognized as the best pitcher or any of that.”19

“Someone that embraces who they are as a person and does something that they think is important to them and not changing based on others’ point of view, I think, is the most important thing that you can draw from [Koufax],” said A’s second baseman Zack Gelof, who played for Team Israel in the World Baseball Classic in 2023.20

Conclusion

Many factors played a part in Koufax becoming the long-lasting paragon of Jewish athletic excellence. A combination of era, talent, personality, and circumstance helped transform him from a mere great ballplayer into something much bigger and more meaningful. The fact that it’s not something he actively sought for himself only adds to his mythos–who doesn’t love a humble, reluctant star?

This raises the question, then: Will Koufax forever reign as the face of Jewish American sports, or could another Jewish athlete one day rise up and take the mantle?

It might just be a matter of time. As we move further away from Koufax’s career and fewer people have firsthand memories of it, that could set the stage for someone else to step into that role. But the circumstances would have to be exactly right.

“The perfect storm is a strong, charismatic Jewish athlete that was as good as Sandy was,” said Kapler. “… I think it’s possible that that comes up again, but it’s got to kind of take a little bit of the stars aligning.”

Then again, there’s a chance that with the passing decades, Koufax’s legend will only grow, firmly cementing his place in history along with a host of other Jewish folk heroes.

“Maybe there’ll be some apocryphal text about [Koufax] a thousand years hence,” said Rabbi Van Leeuwen.

is a reporter/producer for MLB.com. She has been on SABR’s editorial board since 2020. Previously she contributed to Dodgers Digest, The Hardball Times, and FanGraphs. She resides in her hometown of Los Angeles with her husband, Jack, and dogs, Nellie and Boomhauer.

Sources

All stats courtesy of Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 From 1956-1966, just one Cy Young Award was given for both leagues. From 1959 to 1962, the major-league season featured two All-Star Games; Koufax was selected to both in ’61.

2 Interview with David Myers on February 26, 2024.

3 The Six Day War in 1967 was a major inflection point for Jewish American ethnic pride.

4 Scott Ferkovich, “Hank Greenberg,” SABR BioProject. Accessed February 26, 2024. https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/hank-greenberg/.

5 “Profile: Hank Greenberg,” National Museum of American Jewish Military History. Accessed February 23, 2024. https://nmajmh.org/education/individual-profiles/hank-greenberg/.

6 Greenberg had chosen to play on Rosh Hashanah that year, though he did attend morning services. “Hank Greenberg,” Jewish Historical Society of Michigan. Accessed February 23, 2024. https://www.jhsmichigan.org/gallery/2017/05/michigans-first-cemetery-site.html.

7 Michael Beschloss, “Hank Greenberg’s Triumph Over Hate Speech,” New York Times, July 25, 2014. Accessed February 23, 2024. https://www.nytimes.com/2014/07/26/upshot/hank-greenbergs-triumph-over-hate-speech.html.

8 Michael Leahy, The Last Innocents: The Collision of the Turbulent Sixties and the Los Angeles Dodgers (New York: HarperCollins, 2016), 2, 111, 223-224.

9 Interview with Reb Jason Van Leeuwen on February 14, 2024.

10 Jane Leavy, Sandy Koufax: A Lefty’s Legacy (New York: HarperCollins, 2002), 184.

11 Interview with Jim Gilson on February 16, 2024.

12 Peter Dreier, “Chasing Dreams: Baseball and Becoming American,” The American Prospect, August 12, 2016. Accessed February 27, 2024. https://prospect.org/culture/chasing-dreams-baseball-becoming-american/.

13 Interview with Alex Bregman, on June 25, 2023.

14 Recall the joke from the film Airplane! about a “Famous Jewish Sports Legends” leaflet as a “light reading” option.

15 According to Max Fried, this was at the suggestion of mentor Reggie Smith, who offered his own insight while also relaying information on pitching technique from conversations with Koufax. Interview with Max Fried on September 2, 2023.

16 Harold Friend, “Sandy Koufax: The Doctors Were Worried They Might Have to Amputate the Finger,” Bleacher Report, November 28, 2011. Accessed February 25, 2024. https://bleacherreport.com/articles/959588-sandy-koufax-the-doctors-were-worried-they-might-have-to-amputate-the-finger.

17 Abigail Klein Leichman, “10 Things You Need to Know About Yom Kippur,” Texas Jewish Post, October 2, 2022. Accessed February 25, 2024. https://tjpnews.com/10-things-you-need-to-know-about-yom-kippur/.

18 In fact, Koufax had long refused to pitch on Yom Kippur, but it never drew much attention outside of the team before, largely because it had never been in conflict with the World Series. (See Leahy, 113.)

19 Interview with Gabe Kapler on September 22, 2023.

20 Interview with Zack Gelof on August 3, 2023.