Silent Icons: Buster Keaton, Harold Lloyd, and Yankee Stadium

This article was written by David Krell

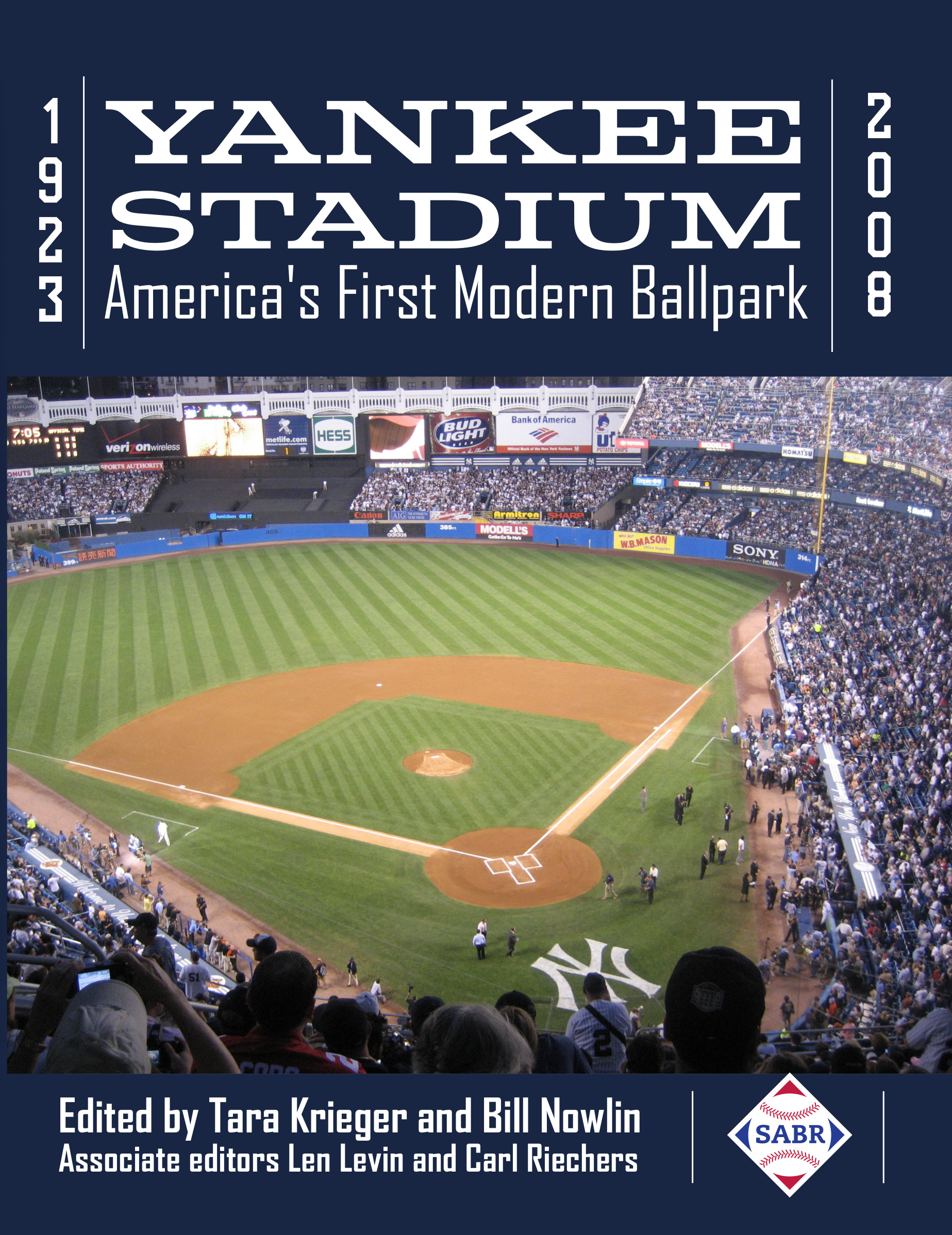

This article was published in Yankee Stadium 1923-2008: America’s First Modern Ballpark

1928 was a phenomenal year for the New York Yankees.

1928 was a phenomenal year for the New York Yankees.

Babe Ruth led both leagues in slugging percentage, home runs, walks, and runs scored as the Yankees marched toward sweeping the St. Louis Cardinals in the World Series and winning their second consecutive title. He also graced the silver screen in Speedy, one of two silent movies featuring Yankee Stadium.

Harold Lloyd plays the title character, a taxi driver who spots Ruth signing autographs at an orphanage. Ruth asks Speedy to drive him to the game; it’s an excruciating trek full of near-crashes with other cars. Yankee Stadium appears as Speedy drives over the Macombs Dam Bridge in a nicely framed shot with the ballpark in the background toward the right part of the screen.

Lou Gehrig appears briefly in the background of a conversation between Ruth and Speedy at the Stadium. The Sultan of Swat asks Speedy if he’d like to see the game, which presents an opportunity to show the field. But the shots are limited to a few moments from newsreel footage; Ruth swings for a strike and then hits a home run. Another player is shown hitting a foul ball.

Ruth was not a stranger to films, having starred in Headin’ Home and Babe Comes Home.

Whether his presence added to Speedy’s box-office success is not known, because Lloyd’s fame was at its height already. But it did offer a valuable piece of verisimilitude, particularly in the establishing shot from the bridge. The audience sees what drivers and passengers see – the Stadium appearing in the distance and getting increasingly imposing as one gets nearer.

It’s one of several New York City locations that Lloyd uses throughout the film; a series of scenes for Speedy’s date with Jane Dillon at Coney Island showcases the area’s iconic attractions in black-and-white glory.

As Ruth biographer Jane Leavy points out, Lloyd knew Ruth’s business manager, Christy Walsh, which explains how the bespectacled silent film star was able to procure the appearance of one of the biggest celebrities in 1920s sports. Ruth’s fee: $5,750.1

Speedy was filmed in the summer and fall of 1927 as Ruth astounded baseball fans by breaking his own home-run record, finishing the season with 60 round-trippers. In one scene, Lloyd holds a copy of the New York Times from August 7. A scoreboard in the window of a sporting-goods store indicates the lineups for a Yankees-White Sox game.

Indeed, the Yankees hosted a two-game series against the Chicago ballclub on August 6-7. The scoreboard indicates Herb Pennock pitching against Ted Blankenship in either the fourth or fifth inning of a game that the Yankees lead 3-1. But the game never happened with the lineups depicted; Blankenship and Pennock did not oppose each other in a game during the 1927 season.

Blankenship pitched on August 7 in a 4-3 loss to the Yankees. Urban Shocker was the starting pitcher for the home squad; he went five innings and was credited with the victory. Wilcy Moore pitched the remaining four innings.

Speedy was a home run for theaters. The Tampa Theater made almost 50 percent of its average weekly gross during the first day that the film – Lloyd’s last in the silent era – was on the marquee. In St. Louis, it took the Ambassador Theater two days to exceed the 50 percent number. The Indiana Theater in Indianapolis tallied 65 percent in the first two days.2

Baseball was just one sport to which Lloyd was devoted. “He loved baseball,” says his granddaughter, Suzanne Lloyd. “He used to take me to the Dodger games. He had a handball court up at Greenacres, his estate in Beverly Hills. That’s how he got his hands strong enough after the accident. He loved to golf and run. Speedy was shot in New York because he wanted it to be totally authentic. His films stand up because they’re true to life. You can relate to them.”3

Ebbets Field or the Polo Grounds could have been used by Lloyd. But 1927 was far from auspicious for Brooklyn – the Dodgers/Robins finished in sixth place with a 65-88 record. The Giants were in third place, only two games behind the pennant-winning Pittsburgh Pirates. With five players hitting above .300 that season – Bill Terry, Rogers Hornsby, Travis Jackson, Freddie Lindstrom, Edd Roush – Lloyd had his choice of top batters. Any player from that quintet would have been known to baseball fans.

But the South Bronx ballpark, then in its fifth season, was a gargantuan edifice famous even to people who didn’t know how many balls equal a walk or what position Lazzeri played for the Yankees. Ruth’s fame ran parallel to the Stadium in the way that sports icons are simply known by the public at large because they transcend their given sport. His success was a huge draw at the Stadium, leading it to be nicknamed The House That Ruth Built.

Yankee Stadium’s depiction in Speedy does not, in any way, match the majesty in The Cameraman, which premiered in September 1928.

The Stadium gave an immediate sense of grandeur with its frieze, size, and mystique. Ebbets Field had charm, contained in a Flatbush city block. You could see Babe Ruth smile if he hit a home run at Yankee Stadium, but you could see Dazzy Vance sweat at Ebbets Field. That’s how close the fans were to the action.

The Polo Grounds had size, but its architecture was unappealing – a bland, horseshoe shape making the fences at the ends of left and right fields less than 300 feet from home plate.

Buster Keaton, a prominent baseball fan in show-business circles, plays the title role – a struggling MGM newsreel cameraman also named Buster – in The Cameraman, which premiered in September 1928. While it’s visually appealing and an example of Keaton’s filmmaking brilliance, the Yankee Stadium scene is not necessary to the plot revolving around a rival cameraman taking credit for Buster’s amazing footage of a Tong War in Chinatown and dating his crush, Sally. In the end, Buster is rightfully credited. Sally winds up with him as the rival is shown to be a cad who also took credit for saving Sally from drowning when it was, in fact, Buster.

At the beginning of the ballpark sequence, Keaton runs across the expanse of the outfield with his camera and tripod, hoping to set them up and capture game footage that his bosses can use for newsreels. Taken from the vantage point of the left-field stands, it’s a beautiful shot encompassing the ballpark’s massive size framed by the famous frieze.

A cardigan-wearing gentleman, presumably a groundskeeper, delivers unfortunate news to Buster – the Yankees are in St. Louis. The timeline tracks with the film’s release. A Yankees-Browns series took place at the beginning of August, in the middle of an exhausting 21-game road trip to Boston, Detroit, Cleveland, St. Louis, Chicago, and Boston again. The Yankees lost two of the three games in St. Louis; they returned to the Bronx with a 10-11 record in the rival cities.

With the gentleman gone, Buster heads to the Yankee Stadium pitching mound and mimes a bases-loaded scenario of trying to pick off a runner at third base; checking the runners at first and second; and directing his right fielder to move toward the foul line. Buster then acts out a double play: fielding a groundball and tossing to the infielder covering second base, presumably the shortstop, then covering home plate, where he jumps to snare a high throw from the third baseman and tag out the remaining baserunner.

Buster continues his imaginary game on offense with an inside-the-park home run, beating the throw – from either an outfielder or the cutoff man – with a headfirst slide into home plate. It’s filmed in one fluid motion, a wide shot keeping Buster in the center of the frame from a point of view behind the left-field foul line and near home plate. The 32-year-old filmmaker sprints around the bases in a 17-second dash. It’s a remarkable feat.

Most prominent in the background of Buster’s run to glory are the advertisement for Gem Razor Blades with the slogan “Never Miss a Whisker” stretching on the outfield wall from right field to center field, and a corresponding men’s grooming advertisement for Ever-Ready Shaving Brushes. The scene ends with the cardigan-wearing man emerging and chasing Buster off the field with a scowl.

Because it’s filmed at ground level, the audience gets a better understanding of the Stadium’s magnificence than they do from the newsreel films shot with cameras in the stands. The scene lasts about 3½ minutes, with Buster’s home run taking up almost a third of that time.

The Yankee Stadium scene in The Cameraman offers a terrific visual chronicle of the celebrated ballpark that housed the iconic 1920s teams anchored by Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, Tony Lazzeri, Waite Hoyt et al. It’s even more impressive in its emptiness; one gets a true, almost eerie, sense of quietude.

Keaton biographer Dana Stevens, author of Camera Man: Buster Keaton, the Dawn of Cinema, and the Invention of the Twentieth Century, believes that the scene exemplifies Keaton’s innovation and appeal. “It brings together some of his best skills as a performer and director,” offered Stevens. “It’s entirely improvised, wordless, shot from a distance in long takes, and shows us not only the mechanics of a ballgame but the psychology of the various players and their relationship to each other – a tour de force of pantomime.4

“The falling house in Steamboat Bill is a breathtaking stunt, but this is a more powerful character moment, and also, because it was improvised on the spot when Keaton and his crew learned that Yankee Stadium was free, is a better glimpse into his working methods than that stunt, which required a specially built set and weeks of preparation. What makes the baseball scene so magical is that it required nothing other than Keaton’s body, a camera and Yankee Stadium.”5

Martin Dickstein of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle highlighted Keaton’s pantomime in his contemporary review of the film: “It is undoubtedly one of the funniest things the screen has brought forth this season.”6

Film exhibitors embraced Keaton’s work, as well. J.M. Reynolds of the Opera House in Elwood, Nebraska, said, “I think I have played every Buster Keaton picture that he has made, and I class this one as one of the best.”7 William Martin of the New Patriot Theatre in Patriot, Indiana, praised, “This is a fine picture with Buster doing his best work that we have seen. Pleased all that saw this.”8

In Pella, Iowa, E.P. Hosack revealed the impact at the Strand Theater: “Buster takes well [here] but I did not know it was so strong – did not put out any extra advertising. If you are strong on Buster, bill it heavy, tie your lobby doors back and start the [show]. Had more laughs in general on this show than I have had for some time – comedy all the way through. Not silly but clever.”9

Inclusions in The Cameraman and Speedy during the Yankees’ prominence in the late 1920s helped begin a long, prosperous, and fascinating journey for Yankee Stadium as a facility of cultural importance in baseball and beyond.

DAVID KRELL is the author of Our Bums: The Brooklyn Dodgers in History, Memory and Popular Culture, 1962: Baseball and America in the Time of JFK, and Do You Believe in Magic? Baseball and America in the Groundbreaking Year of 1966. He has edited the anthologies The New York Yankees in Popular Culture and The New York Mets in Popular Culture. David is the chair of SABR’s Elysian Fields Chapter.

NOTES

1 Jane Leavy, The Big Fella: Babe Ruth and the World He Created (New York: HarperCollins, 2018), 104-105.

2 “Records Go Flooey!” Variety, April 11, 1928: 21.

3 Suzanne Lloyd, telephone interview with David Krell, July 24, 2022. During a photo shoot in 1919, Harold Lloyd severely damaged his right hand when he lit a cigarette with a prop bomb that was actually explosive. He lost a thumb and a finger, which necessitated wearing a special glove in his movies. “Harold Clayton Lloyd (1893-1971),” https://haroldlloyd.com/harold-clayton-lloyd/ (last accessed July 29, 2022).

4 Dana Stevens, email to David Krell, September 30, 2022.

5 Stevens email. In Steamboat Bill, an entire side of a house drops intact to the ground. Keaton’s character escapes harm by standing squarely and unknowingly in a space where an empty window frame will fall around him.

6 Martin Dickstein, “The Cinema Circuit,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 18, 1928: 14A.

7 “What the Picture Did for Me – Verdicts on Films in Language of Exhibitor: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, The Cameraman,” Exhibitors Herald-World, February 23, 1929: 57.

8 “What the Picture Did for Me,” Exhibitors Herald-World, April 13, 1929: 60.

9 “What the Picture Did for Me,” Exhibitors Herald-World, January 19, 1929: 62.