Six-Man Baseball

This article was written by Kevin Warneke - John Shorey

This article was published in Fall 2022 Baseball Research Journal

On the eve of the 1943 season, Boston Red Sox manager Joe Cronin faced a daunting task: replacing Ted Williams and Dom DiMaggio in his outfield. The two All-Stars were serving their country as World War II raged across Europe and the Pacific. Sensing Cronin’s predicament, Associated Press features sports editor Dillon Graham shared a rumor with his readers that Cronin would favor six-man baseball. “You know, just slice off the outfield entirely. Use four deep-playing infielders, a catcher and a pitcher.”1

Graham’s suggestion to his readers may have been intended jokingly, but the idea wasn’t as far-fetched as it may sound. “This, of course, is not unthinkable,” Graham wrote. “Football, in some sections, has blossomed as a six-man sport and, baseball men are quick to say, whatever football does, baseball can do, and better.”2

Graham knew about the recently introduced sixman version of football, but apparently was unaware that its inventor also had designed an alternative to traditional baseball. Stephen Epler, who devised sixman football during the Great Depression as a way for high schools with smaller enrollments to field teams, introduced a six-man version of baseball in 1939 as a sequel. Epler, who coached and taught at Chester High School in Nebraska, would later serve in the US Navy, found two institutions of higher learning, and serve as president of a third.3

Epler suggested six-man baseball might be best suited for younger players.4 “Probably the greatest field for six-man baseball is the playgrounds, sandlots, and the intramural field,” Epler wrote. “Like its brother, six-man football, it speeds up the action and makes the game more fun for the players.”5

Six-man baseball made inroads after being featured in American Boy magazine in 1939. “Six-man baseball probably has advanced further in the past year than six-man football did in its first year,” Epler wrote.6 The article, published in the May 1939 edition, noted that six-man football, which he had invented four years earlier, was played in 2,500 schools throughout the country at the time. “Here, for the first time, are formal rules for the (six-man) game—rules designed to make the game yield maximum fun and thrills for the player!”7

Epler shared the rules, which included accommodations for use in softball, in American Boy and the Journal of Health and Physical Education. He stated that the main rules for baseball would still apply, but with six main adjustments:8

Rule 1: Each team consists of six players: a catcher, pitcher, two infielders (which he called basemen) and two outfielders (called fielders).

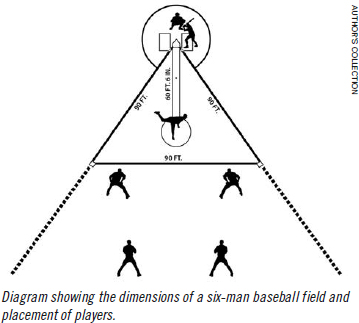

Rule 2: The playing field has three bases, including home, which are an equal distance (standard 90 feet) apart to form an inverted equilateral triangle (at 60-degree angles instead of 90-degree). The pitcher’s rubber remains at the traditional distance of 60 feet, 6 inches from home plate.

Rule 3: Two strikes make an out, with a foul ball counted as a half-strike. Four fouls make an out. Three balls earn the batter first base. Each batting side has four outs each inning. A game is six innings. “At the end of six innings you will probably be more tired than at the end of nine innings of nine-man baseball so this is made the official length for six-man baseball.”9

Rule 4: No player shall wear metal spikes or hard cleats. “The fourth rule does not affect the actual playing but is needed to eliminate unnecessary injuries.”10 Epler suggested players wear shoes made from soft materials similar to those worn in softball, basketball, and six-man football competition.

Rule 5: Players may change positions at any time, if Rule 6 is in play. A pitcher cannot be replaced during an at-bat.

Rule 6: After each batter has finished his turn, the team in the field rotates positions. The order: pitcher, first baseman, right fielder, left fielder, second baseman, catcher and back to pitcher. (Epler allowed that position rotations in baseball could be made after every fourth batter, partly to eliminate the need for a different player to don the catching gear after each batter). “Rotation gives boys practice in every position and helps them learn baseball from A to Z.”11 Epler noted that rotating players in the field evens the playing field. “A team with nothing but a good pitcher will not win many games.”12

Along with the rules, Epler listed the following attributes of his version of baseball:

- Players bat every sixth time. “The more you bat the better hitter you will be.”13

- With only six to a side, fielding a competitive team will be easier. “The result is less standing around and more action for every player.”14

- Six-man baseball’s rules and the layout of the field will lead to more action, which means more scoring. A batter has to touch three bases to score instead of four. “You will like higher scores because the most fun after socking the apple is sliding safely into home plate.”15

- Through player rotation, weaker players from opposing sides could be matched against one another.

Six-man baseball also received attention in Popular Mechanics in 1939. “Six-man baseball requires a smaller playing field and less equipment than its big brother, and permits wider flexibility of the rules.”16 Six-man baseball also protects players from overdoing it in competition. “Rotation in games between office league oldsters should prevent a lot of sore-arm trouble for those middle-aged would-be athletes who insist on pitching the full game and then spend the next three days beefing about ailing arms.”17

Epler, in his American Boy article, rallied support for his game, thus: “So get out on the diamond, the first sunny day, and play baseball the six-man way. Play it for just one week to prove that you like it. Get the old glove out, limber up your arm, take a few grounders, then pick up the bat and—Play ball!”18

He apparently had some early takers on his suggestion to try his version of America’s favorite pastime. Some examples:

- Coaches and physical education instructors taking a summer coaching class in 1939 at Columbia University’s Teachers College participated in a demonstration game umpired by former big leaguer Ethan Allen. Said Professor F.W. Maroney: “Simple organization, inexpensive equipment, and an opportunity for every boy to play every position are three attractive features that the six-man game has to offer.”19

- Epler participated in a coaching clinic in Victoria, Texas, in August 1939 that included a demonstration game featuring players from York Oil and St. Joseph.20

- A report for Transradio Press in June 1939 touted the success of six-man baseball at Roosevelt Junior High School in St. Joseph, Missouri. Coach Jimmy Streeter, who predicted success for six-man baseball, said: “There is a lot of action and plenty of chances to bat. And after all, most players fancy the batting more than any other part of the game.”21

- Ken Corcoran wrote in the Boys Town Journal in 1940 that he would introduce boys living at Father Flanagan’s Boys’ Home near Omaha, Nebraska, to six-man baseball.22

- Even as late as 1953 newspapers throughout the country featured a story explaining the rules of six-man baseball. The correspondent summarized his article with the following statement, “Besides being a fine game for the players, six-man is also a good spectators’ contest. Why not get your teams ready now and start a game on the nearby baseball field.”23

Despite the positive accolades that this version of baseball received, not everyone was smitten with Epler’s creation. In 1940, Dick Hackenberg, a sports staff writer for the Minneapolis Star, penned an editorial in which he imagined Abner Doubleday turning over twice in his grave. “‘Why, oh why,’ wailed Mister Doubleday, ‘don’t they leave things alone, anyway? Who is this Stephen Epler? Where’s he ever get that silly idea?’”24 Continuing his tirade for the fictitious Doubleday, he addressed some of the specific rules with which he took exception, “‘It is pointed out that the batter must hit into a 60-degree angle instead of 90, which will develop more accurate hitting—yeah, to the fielders. Accurate hitting in nine-man ball is down the lines or between the fields. In six-man, a guy either would be out P.D.Q. on four of those half-strike fouls—which might be doubles or triples ordinarily—or he’d hit the ball into a concentrated fielding area. Pooey!’”25

Robert McShane, in his newspaper column “Speaking of Sports,” wrote about Epler’s game in 1939 and his story was carried in newspapers throughout the country, saying, “Spectators said very plainly that it wasn’t exactly baseball. That didn’t bother Epler, who more or less agreed with them. He introduced the game to please the players not the fans.”26 Apparently those spectators were correct. The game didn’t catch on like its predecessor, six-man football, which is still played in high schools throughout the country, including in Nebraska where Epler lived when he invented it.

One of the most expansive critiques of Epler’s baseball variant came in 1940. Early that year, the Des Moines Register published a story describing the rules of six-man baseball. After reading the story in the newspaper, the baseball coaches at two small high schools in Southwest Iowa arranged two experimental games of six-man baseball to see whether the game had real possibilities beyond playground adaptation.27

One of the most expansive critiques of Epler’s baseball variant came in 1940. Early that year, the Des Moines Register published a story describing the rules of six-man baseball. After reading the story in the newspaper, the baseball coaches at two small high schools in Southwest Iowa arranged two experimental games of six-man baseball to see whether the game had real possibilities beyond playground adaptation.27

“Defiance jumped on Tennant pitching for ten runs in the first inning to help win one of the first six-man baseball games in the state, 11 to 0.” proclaimed the brief story from the Council Bluffs newspaper.28 After the two experimental games coaches Tom Orr and William Nechinicky shared their analysis with Des Moines Register sports editor Sec Taylor. The experimental games led the coaches to the conclusion that “six-man baseball can never be a strong contender with the nine man sport.” The Iowa prep coaches shared the following observations with the newspaper:

- “The two strikes do not enable the batter to look the pitcher over. Many hitters prefer to let the first strike go by. With only two strikes this would be most detrimental.”

- “Any team that could develop two or three place hitters that could hit the ball just over the pitchers head to the edge of the infield or any distance beyond would have a great advantage. This takes away the long-hit thrills of the game.”

- “Stolen bases are at a premium due to the nearness of the two bases to home plate and the pitchers mound. This also eliminates many thrills of the long throw to second base to pick off a coming base runner.”

- “A two-man infield is not adequate to cover ground balls hit at a fair clip or to cover bunts and at the same time protect the bases. There is just too much space for two men.”

- “It is impossible to bunt unless done on the first strike. This eliminates many would be sacrifices and another of the thrills of the nine-man game.”29

Decades later, Larry Granillo, writing for Baseball Prospectus, examined Epler’s version of baseball. Granillo pointed out that the game, on offense, wouldn’t change much, except for the pace of play. “Defensively, however, is a different story.” The infielders, to be effective, would have to move up, similar to a drawn-in infield. “We all know how that plays out— anything that isn’t a weak grounder would fall in for a hit due to the decreased reaction time the fielders would have.”30

The outfielders would have even more difficulty. The 60-degree foul lines would lessen the ground they needed to cover, but they still must cover the power alleys. “This is possible with two quality fielders, but would mostly result in more hits. And, with all the extra grounders they’d be forced to field due to the infielders’ poor reaction times, the two outfielders would find their job that much harder and more tiring.”31

Granillo acknowledged that Epler’s game wasn’t created for “full-on major league play,” but rather for kids. He lauded Epler’s invention and praised the “very cool looking field,” but said the increase in offense at the expense of defense wasn’t worth it. “Of course, if I were a ten-year-old kid hoping to get a full game of baseball in at recess with my schoolyard friends, I might be singing a different tune.”32

KEVIN WARNEKE, who earned his doctoral degree from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, is a fund raiser based in Omaha, Nebraska. He co-wrote The Call to the Hall, which tells the story of when baseball’s highest honor came to 31 legends of the game.

JOHN SHOREY is a history professor emeritus from Iowa Western Community College where he taught an elective course on Baseball and American Culture for 20 years. He has published articles on a variety of baseball topics and has presented at the Cooperstown Symposium on Baseball and American Culture and other baseball conferences.

SIX-MAN BASEBALL ALL-TIME TEAM

Six-man baseball, had it been widely accepted, would have caused major league teams to re-evaluate their talent, with a call for those who could play multiple positions. And had six-man baseball endured, the authors suggest that those selected to an all-time six-man team possess some or, all, of these qualities:

- Hall of Fame or multiple All-Star selections

- Pitching experience in high school or later

- Gold Glove Award winners (especially pitchers)

- Catching experience in high school or later

- Experience playing multiple positions at the professional level

- OPS at .850 or higher

The authors’ all-time six-man roster in this batting order would be:

Craig Biggio: A Hall of Famer who broke in as a catcher, and then played second base and center field. He is the only player in MLB history with at least 3,000 hits, 600 doubles, 400 stolen bases and 250 home runs. Despite switching positions, he won four Gold Glove Awards.

Pete Rose: He broke into the majors as a second baseman, but also starred as a corner outfielder, as well as playing first and third base. In high school, he caught and played shortstop. Rose could serve as the team’s player-manager.

Babe Ruth: His batting exploits included a .342 average and 714 home runs, along with 2,214 RBI, 136 triples, 506 doubles and 123 stolen bases. His career OPS was 1.164. His best season as a pitcher was 1916, in which he won 23 games with a 1.75 ERA. He caught for his high school team.

Charles Wilber “Bullet” Rogan: Hall of Famer Rogan was one of the best two-way players in the Negro Leagues. His career pitching record was 120-52 with a 2.65 ERA. As an outfielder and second baseman, he typically batted fourth, producing a .338 career batting average and 106 stolen bases.

Dave Winfield: He was drafted by the NBA, ABA, MLB and even the NFL, despite never playing football in high school or college. As a collegiate pitcher, he boasted a 9-1 record his senior season with a 2.74 ERA. He was a five-tool player with four seasons in the majors of 20+ stolen bases to go with 465 career home runs.

Stan Musial: He began his baseball career primarily as a pitcher, going 18-5 with a 2.62 ERA in his third season in the minors before switching to outfield and first base. Musial finished his career with a .331 batting average, 475 home runs, 1,951 RBI and 78 stolen bases. He had a career OPS of .976 and held or shared 17 MLB records when he retired.

Notes

1. Dillon Graham, “Manpower Shortage Hits Cronin And He’d Like 6-Man Baseball,” Marshall (Texas) News Messenger, April 13, 1943, 6.

2. Graham.

3. SFGate, https://www.sfgate.com/news/article/OBITUARY-Stephen-Edward-Epler-2831735.php, retrieved October 18, 2022.

4. Stephen Epler, “Try Six-Man Baseball,” The Journal of Health and Physical Education, 11:6, 367, 384.

5. Epler, “Try Six-Man Baseball,” 367.

6. Epler, “Try Six-Man Baseball,” 367.

7. Stephen Epler, “Play Six-Man Baseball!,” The American Boy, May 1939, 5.

8. Epler, “Play Six-Man Baseball!,” 5, 36.

9. Epler, “Play Six-Man Baseball!,” 5.

10. Epler, “Play Six-Man Baseball!,” 5.

11. Epler, “Play Six-Man Baseball!,” 26.

12. Epler, “Try Six-Man Baseball,” 367.

13. Epler, “Play Six-Man Baseball!,” 5.

14. Epler, “Play Six-Man Baseball!,” 5.

15. Epler, “Play Six-Man Baseball!,” 5.

16. “Six-Man Baseball Played on Triangular Field,” Popular Mechanics, December 1939, 881.

17. Fred Browning, “That Guy With ‘6-Man’ Ideas is Back—Now It’s With ‘Abbreviated’ Baseball,” The Evening News (Sault Sainte Marie, Michigan), August 30, 1939, 8.

18. Epler, “Play Six-Man,” 36.

19. “Coaches at Summer Session Demonstrate 6-Man Baseball,” Northwest Nebraska News (Crawford, Nebraska, August 24, 1939, 2.

20. “Six More Join 6-Man Coach School Here,” Victoria (Texas) Advocate, August 29, 1939, 1.

21. “Missouri High School Coach Finds Six-Man Baseball Successful,” The Morning Spotlight (Hastings, Nebraska), June 17, 1939, 5.

22. Ken Corcoran, “Corcoran’s Sports Highlights,” Boys Town Times, April 12, 1940, 3.

23. Emmett Maum, “Six-Man Baseball Is Ideal For Neighborhood Groups,” The Sandusky Register, May 28, 1953, 16.

24. Dick Hackenberg, “Millers Could Leave Only Two on Base in Six-man Baseball,” The Minneapolis Star, May 19, 1940, 22.

25. Hackenberg, “Millers Could Leave Only Two.”

26. Robert McShane, “It’s Two Strikes And Out at the Old Ball Game,” Mountain View (Oklahoma) Times, October 26, 1939, 3.

27. Sec Taylor, “Six-Man Baseball,” The Des Moines Register, May 15, 1940, 9.

28. “Wins Six-Man Baseball Game,” Council Bluffs Nonpareil, April 21, 1940, 18.

29. Taylor, “Six-Man Baseball,” 9.

30. Larry Granillo, “Wezen-Ball: Analyzing ‘Six-Man Baseball,’” Baseball Prospectus, August 4, 2011.

31. Granillo, “Wezen-Ball.”

32. Granillo, “Wezen-Ball.”