Smoky Joe Wood’s Last Interview

This article was written by Franz Douskey

This article was published in The National Pastime (Volume 27, 2007)

Author’s note: I met Joe Wood in the early 1980s after I called and said I’d like to interview him. His daughter invited me over. Joe and I spent a lot of time together, often watching Red Sox games on television and comparing players from different eras. All this was before a taped interview, which took place on May 11, 1984. When he was up to it, I saw Joe a few times after that. He died in July 1985.

FD: How did you first break into Organized Baseball?

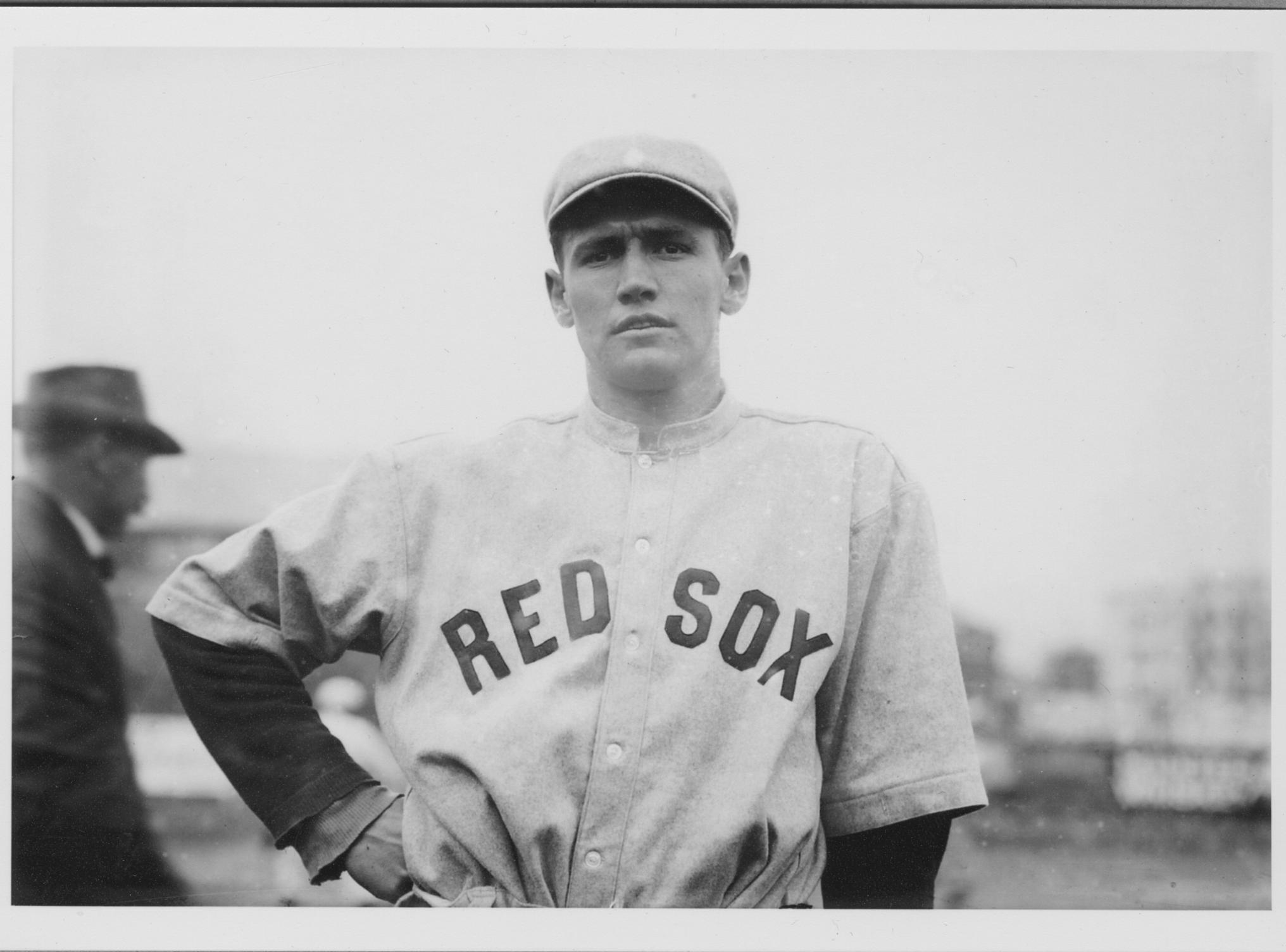

SJW: It was an all-girls team. The National Bloomer Girls were out of Kansas City run by Logan Galbraith. We had moved to Kansas, where my brother was born, in 1887, two years before me. My father was an attorney, and I was playing on the town team when the National Bloomer Girls came through. They had three more weeks of their season and they needed a shortstop. I wasn’t the only male on their team. They offered me 20 dollars to play with them, and I thought, “My God, that’s a lot of bucks.” I told my folks and they said I could go. The season ended in Wichita, and they gave me my fare home. That was my first baseball experience. Soon after my brother ran into Ducky Holmes, a former major leaguer. He told Ducky that he had a kid brother who’s a pretty good ballplayer. How about getting him a job in professional ball? Ducky contacted the owner of the Cedar Rapids Club, of the Three I League, owned by Belden Hill. I signed as an infielder, for 90 dollars a month. But I never reported to Cedar Rapids, because Belden Hill wrote me and said he had too many infielders. He used to visit me during 1912, the year I won 34 games, and he used to curse his bad luck for not letting me report to him in the first place, but transferring my contract to Jay Andrews, who was managing the Hutchinson club in the Western Association. Hutchinson, Kansas, was only 116 miles from where I lived, by way of the Santa Fe railroad, so I was tickled to death. My dad took me down and in troduced me to Jay Andrews and some of the players like Skinny Horton, Flea Hardy, Turk Dunnum, and they all had sore arms. Jay Andrews came up to me and asked, “Joe, can you go in and pitch a little.” I said I’d go in, and then they never let me out. Then I was sold to Kansas City. We played against several major league clubs as they were coming up from the South from spring training. In August 1907, I was sold to the Boston Red Sox. Fred Lake came down to look at me, and John R. Taylor, who was the president of the Red Sox at that time, sent me a contract for $2,400. That was 400 dollars a month for six months. Instead of going to Boston, I went back home and told Mr. Taylor he’d have to come up with more money before I’d report to Boston. When I got to Boston, I was single, and you know how women chase after ballplayers. I used to tear around quite a little, but I still pitched good ball for them. I asked for more money. Taylor, the president of the club, said, “Whenever you decide to get your feet on the ground and pitch good baseball, we’ ll give you the money.” So I went right along, from 1908 on. In 1911, I had a pretty good year. 23-17.

FD: In 1908, when you came up from Kansas City at age 18 to pitch for the Red Sox, did you room with Tris Speaker right from the start?

SJW: That was a coincidence that happened, and run into a friendship that lasted forever. When I went to the Red Sox, that was August 1908. Speaker had joined the Red Sox in 1907. They sent him to the Southern League and he led the league in hitting. He came back to the Red Sox about a week or two after I did, and it just so happened our secretary, Eddie Reilly, put Speaker and me as roommates. And we were roommates for 15 years. Even in Cleveland, where he was instrumental in bringing me there.

FD: You had a remarkable year in 1912. Thirty-four wins, five losses. Three wins in the World Series. You were 21, at the start of a spectacular career. Then in the spring of 1913, you slipped fielding a groundball and broke your thumb.

SJW: That was the last time I ever pitched a good ball game. At the same time something happened to my shoulder. Was it because I changed my motion? I’ll never know. The same thing happened to Dizzy Dean. You do some damn thing to protect what the trouble is and that way something else develops, and that’s it. We never know.

FD: You did come back to a degree. You were 10-3 one year, then 15-5.

SJW: Well, Christ, I only pitched half a season. I couldn’t throw a ball. Couldn’t raise my arm for three weeks. We had to keep playing ball to keep our contracts. I only pitched two full seasons in the big leagues, 1911 and 1912. The rest are all half seasons. One year I had appendicitis. The next year I had a busted artery in my leg, my ankle. Had it cut out, then I had a broken toe. And that’s how it went. The last year I pitched, in 1915, I led the league in earned run average, but it was only a partial year. And that’s why it’s a problem for the Hall of Fame. I’m not interested in the Hall of Fame. I tried to get my son to not bring it up, but he wanted to do it. I told him I had no interest in it.

FD: You may not want it. But when I speak with players from your era, and with baseball historians, your name does come up.

SJW: I know that, but I just didn’t have enough consecutive full-year time. I don’t give a damn about it. I have no interest whatsoever in being in the Hall of Fame. It’s all political. There are players in there that weren’t even considered good ball players in my day. If there were any players who played in my heyday on the committee, I’d be in there. I know that. They talk about fastball pitchers. Walter Johnson said there was nobody faster than me, and that’s true. If anybody could throw faster than me, it was Walter Johnson, so he’d know. In those days we didn’t have any ways of measuring. I talked to Larry Lajoie and Honus Wagner. I pitched against them in exhibition games, because they trained in Hot Springs, same as the Red Sox. They stayed at the Easton Hotel; we stayed at the Majestic. I pitched against Lajoie, Wagner, and Cobb, and they’d give you their honest opinion. Nobody was faster than me. I keep appearing in books like The Glory of Their Times, The Ultimate Baseball Book, and The Greatest One Hundred Players of All Time. I appreciate it, but I pitched with a bad arm. Come the 1915 World Series against the Phillies, Bill Carrigan came to me and asked, “How’s your arm, Joe?” “Terrible,” I told him, “but if these fellows can’t carry you through, I’ll go in there.” That’s why I was in the corner, in the bullpen, every day. It was Foster, Leonard, Shore, and Mays who pitched us through. My arm was terrible. That’s why I laid out the 1916 season, I couldn’t even raise my damned arm. Just like today, you get my left hand when we shake hands. The X-rays show there’s nothing in my right shoulder joint whatsoever. It’s bone against bone. I haven’t slept on my right side since back then, 1913. Almost 70 years ago. But that’s what happened. Nowadays, they’d probably give a shot of cortisone in there or take a rest. Whitey Ford said when he’d get a little kink in his arm, he’d take a little rest for two or three weeks. Not only that, they pitch you once every five days now. When I played, it was every fourth day. All those things go into the thoughts of what happened. l’ll never know except I pitched hard when my arm was sore. I even pitched when I was in so much pain, I had to use my left arm to get my right arm into the sleeve of my coat.

FD: You once rigged a trapeze in an attempt to rehabilitate your arm.

SJW: That’s right. I hung one in my attic, in Pennsylvania, in the home I built in 1913, the year I got married. I couldn’t throw a ball 10 feet. I thought it might stretch my arm out. I hung from it all winter long, but it didn’t do any good. Even now, when I threw out the first ball at Fenway this spring, I threw it left-handed. Why did I hang from a trapeze all winter? The whole reason is that people who played baseball when I played baseball loved the game. They would have played for nothing. The boys who play now are just there for what they can get out of it. You take Fred Lynn. A whale of a ballplayer. Get a sore throat and he’d want to come out of the ball game. I’ve thought about him a lot. He could have been another Ty Cobb, but he didn’t have the temperament. Every damn little thing and he’d want to get out of a ball game. Not giving to his capabilities. I’ve often thought about that. Players seemed to get results from a chiropractor, in New York, named Crusius, so I went to him. I went to him all during the winter of 1915 and the spring of 1916. I worked out in the Columbia University gym all winter, and I got to the spot where I thought it was all right. I got a call from (Tris) Speaker. He had moved from Boston to Cleveland. He asked how my arm was and I told him it was all right. I thought it was. I never lied to anyone in my life. I joined the Cleveland club and it was the same damn thing. The only way I knew how to play outfield was that this was the start of the war, and all the eligible men were going into the Army. Well, a lot of former major leaguers were in the minors and they were calling them back up in order to fill out the team. One day, Eddie Miller, was playing left field, and he got hit in the chest with the ball. (Laughs.) So, they put me out there and I started hitting. I knew damn well if I was going to play the outfield I’d have to hit more than I did when I pitched. I choked up on the bat and got a lot of hits and hit pretty well. Hit about .380. But I was always a family man. I’d go on a trip for three weeks, and when I’d get home, my boys didn’t know who I was. For thatreason I left baseball and eventually got to be the base ball coach at Yale, in 1922. I grabbed that job in a minute because I wanted to be with my family more than I wanted to be just playing baseball. I coached baseball at Yale for 20 years. And I bought this house right here, and my wife was always crazy about this house. She passed away three years ago this month. My daughter and her husband were nice enough to move in with me so I wouldn’t be alone.

FD: How has the game changed over the years?

SJW: They think winning 20 games is a hell of a stunt. When I came up in Boston and you only won 20 games, it was a bad year. Absolutely. In my day a pitcher could no more catch a ball in one hand, with the glove on, than he could fly. You very seldom saw a backhand play. You see them every day now. Gloves are huge. The ball gets lost in them. You can’t miss. They have a hard time get ting the ball out of the glove. I can remember when I first broke into the league, when Stuffy Mclm1is came in with the Athletics with his big glove, the first baseman’s trapper mitt. He led the league in fielding five years in a row [Ed. note: six times but only three in a row, 1920-22]. That was the first big glove I ever saw. Stuffy McInnis was one of the fellows who came up to you at the tail end of a season, when it didn’t matter, and say, “Look, it doesn’t matter to you, let me get a hit or two and I’ll get picked off or caught stealing, or some damn thing.” It wasn’t wrong; it meant a little bit more to him to have a hit or two on his batting average. He’d get picked off or slow down on his way to second base. But he never used it to his advantage, betting or anything like that. The gloves are bigger and the ball is much livelier because they want to get the crowds in, and so on. The catcher catches the ball with one hand. If they caught the ball with one hand and dropped it years ago, they would’ve been fined. Now they all catch one-handed. We never caught the ball above our heads like the fielders do now. We caught it down low, what we called the basket catch, because you caught it near your bread basket, your stomach, and that way you were ready to throw. Another way the game has changed is they have a coach for the catcher, a coach for the pitcher, a coach for hitters, and bullpen coach, a running coach, seven or eight coaches. In my day we learned from each other. We talked about the various things that happened in the games we played in. If you didn’t learn, you didn’t stay around for very long. But now, my God, the pitching coach goes out first, then if they’re going to take the pitcher out, the manager goes to the mound. The age of specialization. Sometimes I hardly recognize it as baseball.

FD: Often, one ball lasted the entire game, and it wasn’t necessarily round at the end of nine innings. Pitchers occasionally doctored the ball. Did you ever throw a shine ball, mud ball, or coffee ball?

SJW: Didn’t need to. A coffee ball was the same as a mud ball, getting the mud to stick on. Some of the fellows used paraffin and hid it in their trousers. Eddie Cicotte used it. We called him “Knuckles.” We called it a shine ball. Rub the ball on the paraffin on his pants. He was on the Red Sox when I come up. He got caught up in the Black Sox thing, which ended his career. I don’t know too much about that. Of course some used slippery elm to throw a spitball, Stanley Coveleski used it, which was perfectly legit. You were allowed to have one or two pitchers on the club who threw it. Al Sothoron was not supposed to throw it on Cleveland, but he did use it. Every once in a while an umpire would ask to see the ball. Instead of throwing the ball, Al Sothoron would roll the ball on the ground so it would pick up dirt. Ed Reulbach had the mud ball. Buck O’Brien on our club, he had a razor blade inside of his glove.

FD: Lets talk about players who should be in the Hall of Fame but aren’t. For example, Carl Mays had an outstanding career, but then there was the Ray Chapman incident, the only player to be killed playing major league baseball.

SJW: Carl Mays should never be in anyone’s book. I don’t know how true it was, but we heard that Mays threw at Ray Chapman intentionally. I was one of the ones that carried him off the field. Chapman was a grand person. Mays went and got the ball and threw to first base, claiming Chapman was out. We heard right after the game that Mays said he was going to get Chapman. A grand person.

FD: Which players have been overlooked by the Hall of Fame?

SJW: We had a third baseman on the Red Sox. A clutch hitter all through his career, and you never hear his name mentioned. I wouldn’t trade him for ten Frank “Home Run” Bakers. His name was Larry Gardner. A hell of a ballplayer. Loved the game. Graduated from University of Vermont with Ray Collins. He was more valuable to the team than Harry Hooper, but you won’t see that anywhere. Pepper Martin was the same way. He’d tell the catcher he was going to steal, but they seldom got him out. And Pete Reiser was a great ball player. Ran into too many walls, but he loved to play.

I can name you a lot that should’ve been forgotten and weren’t. I’ll give you one and he’ll admit to himself: Eppa Rixey. Do you know that name? He said that when they picked him [for the Hall of Fame], they must’ve gone to the bottom of the barrel. That’s right. He was never a top-notch pitcher. Tom Seaton and George Chalmers and Grover Cleveland Alexander were on his team, and they were better pitchers. Eppa was a hell of a fine guy, but nowhere close to Seaton and Chalmers, both forgotten. Rabbit Maranville has no business in the Hall of Fame. Neither does Ray Schalk or Frank Baker. Nine or ten home runs a year and they call him “Home Run” Baker. I know Frank Baker very well. The only time I went through the Hall of Fame, I went with Frank Baker. Had my picture taken with him. My God, so many players in there that weren’t even considered good when they played. You never know how good a player is until you’re on the same club together. You take Sam Rice. A fine fellow and a good player with Washington. When he got into the Hall of Fame, he said, “If you want to know who should be in the Hall of Fame, I can name them for you. Honus Wagner, Larry Lajoie, Tris Speaker, and Ty Cobb.” He said there are six or eight of those and that’s it. The rest of us, it’s a different thing. That’s the way he described it. Sam Rice said, “Other fellows got in there that shouldn’t be in there. And I question whether I should be in.” And Sam Rice was right.

FD: Do you think Shoeless Joe Jackson should be in the Hall of Fame?

SJW: Well, I don’t think he’ll get in unless they exonerate him of all liability in that scandal. He had the reputation and all, and. this is only hearsay, that he could not read or write. I know this. Another thing that was told to me that Joe and his roommate would go out for meals. Whatever his roommate ordered, Joe would say, “Bring me the same,” because he couldn’t read the menu. But I don’t think Joe Jackson would honestly throw anything. No, no. The ringleader was Chick Gandil. Abe Attell, the prize fighter, was the middleman, so they say. Joe Jackson hit .375 in that series, and he hit the only home run. And he didn’t make any errors, so I don’t know. You know, we ballplayers used to talk together, and I remember those who played with him considered him the greatest natural hitter there ever was. And that was amongst the players who knew him! About him teaching Babe Ruth how to hold a bat and swing, I don’t think there’s a bit of truth to that. And remember, I played against both of them, and Ruth was a teammate of mine with the Boston Red Sox when he came up. Babe Ruth was an absolute natural, like Joe Jackson. Eddie Cicotte, Charlie Hall, Ruth, Eddie Carter, and I used to go out at noon to pitch batting practice to each other, because, in those days we had to hit. And we had some damn good-hitting pitchers. I think Walter Johnson hit better than .250 for his career, and could hit home runs, even with that dead ball. And you know about Babe Ruth.

FD: Who was the toughest hitter you faced?

SJW: Oh, hell, most all of them. One fellow from St. Louis was as good as I ever pitched to. Some days I can remember his name, some days I can’t. Pete somebody, I think it was. Sam Crawford of the Detroit club hit me a hell of a lot harder …. Eddie Collins used to hit me hard. What the hell was his name. Pete somebody. St. Louis Browns. I know you never heard of him [Pete Compton]. He could hit me. Jesus. I couldn’t get a ball by him.

FD: What about your own career?

SJW: I was 115 [now credited with 117 wins], wins and 57 losses, better than two out of three games. And my lifetime ERA was 2.03, just behind Ed Walsh and Addie Joss, third on the all-time list. And one year I hit .366 with Cleveland, a lifetime batting average of .298 [Ed. note: .283]. Not too bad for a man who couldn’t lift his arm. And they list me as the Red Sox’s greatest pitcher, and that includes Cy Young, who had some great years in Boston. And that’s the gospel truth. Just like I used to tell my kids when they were growing up. “Always tell the truth and you don’t have to remember what you said.” I can go over my career till my dying day and come up with the same figures. All I know is that there was no one faster than me. But I don’t care about it. I had my day and it’s over, and that’s it.

FRANZ DOUSKEY has published in The New Yorker, The Nation, Rolling Stone, Yankee, Down East, SCD, Baseball Diamonds (Doubleday & Company), and dozens of other publications. He has taught at Yale University, lectured at the Harvard Graduate School and is President Emeritus of IMPAC University.