Softball and Swastikas: The Riot at Toronto’s Christie Pits

This article was written by Stephen Dame

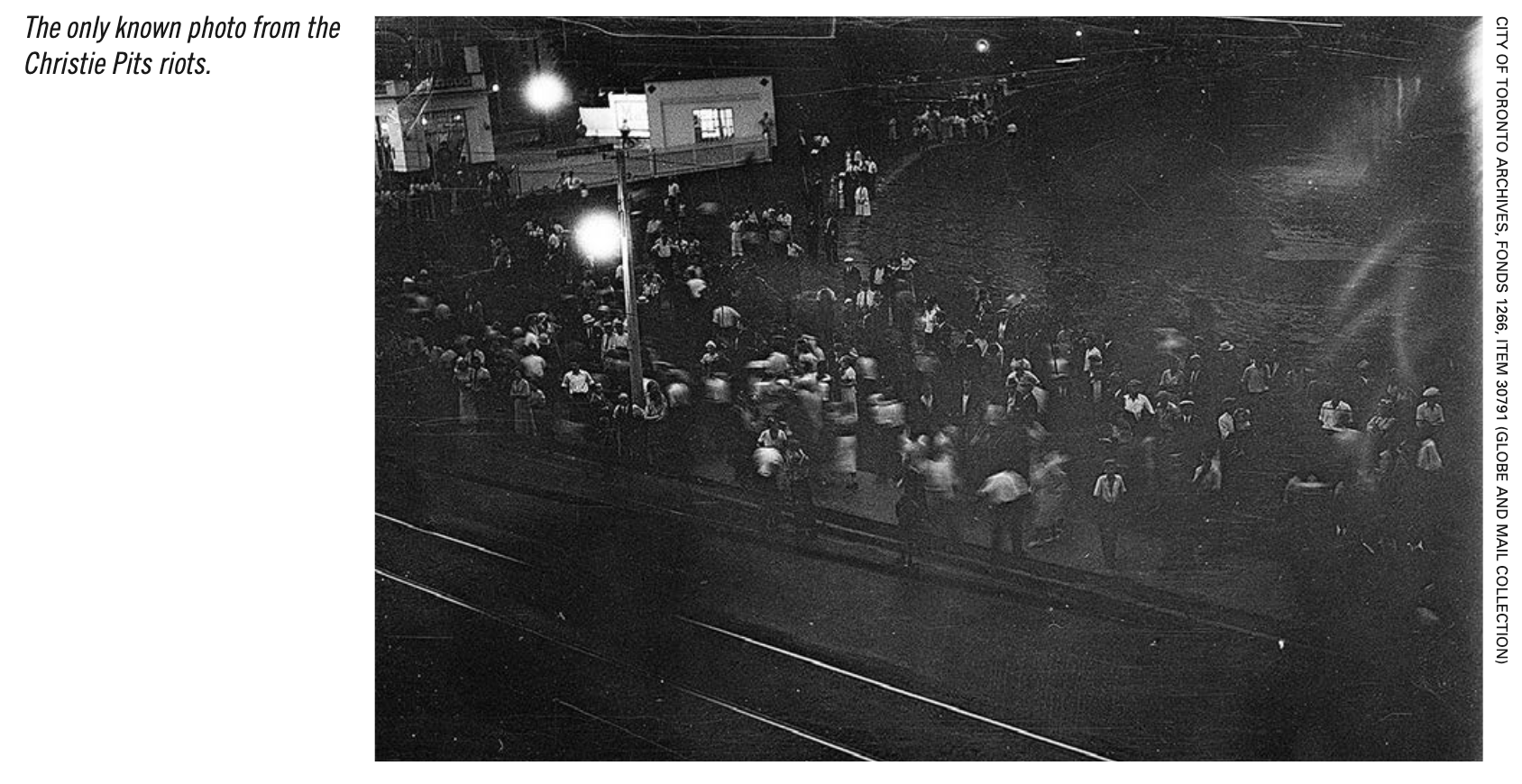

This article was published in Fall 2023 Baseball Research Journal

Toronto’s worst incident of civil unrest happened in one of its most storied ballparks. More than six hours of brawls, bloodbaths, and beatings were unleashed at the corner of Bloor and Christie streets because of tensions built during 15 years of postwar animus. It was a race riot, it was a lawless free-for-all, it was a surge that menaced the innocent. It was also the oppressed launching a counterstrike against their oppressors during nine innings of junior softball. The riot at Christie Pits Park permanently scarred the city of Toronto and its perennial branding as tolerant, orderly and just.

FROM SANDPIT TO SANDLOT

Ball diamonds were a late addition to the landscape north of Toronto’s downtown Bloor Street. Garrison Creek ran freely through what is today Christie Pits until the City of Toronto turned the creek into a storm sewer before the turn of the twentieth century. A natural sand mine was then established within the steep creek valley. The Christie Street sandpit was used to combat icy walkways and thoroughfares. The sand was also mined to repair eroded beachfronts, create abrasives, produce cement, and, of course, lay baseball infields. There was even a rush on city sandpits during an ill-advised fad of people eating sand to clean out their stomachs and toughen their skin.1 To both the municipality and the “sand eaters,” the desert in the Christie sandpit was preferable to the sands of Lake Ontario, which often included shells, refuse and avian waste. Colloquially and immediately, the city facility became known as Christie Pits, complete with its extraneous final “s.”

In the winter of 1905, the City of Toronto was under pressure to create more civic spaces for families, specifically playgrounds. Mayor Thomas Urquhart told interested parties that converting sandpits was the most convenient and affordable option.2 A year later, the city purchased and demolished the two houses bordering the edge of the Christie Street sandpit for a total of $3,020. A plan was announced to convert the pit and its immediate surroundings into a public park.3

The conversion from pit to playground took time and gruelling work. Piles of sand needed to be hauled out of the pit and dispersed along the city’s beaches, using shovels and wagons. Grading work would then need to fill holes and flatten earth. A few months into the arduous tasks, James Swan was standing on low ground, shoveling sand into a pile above his head. The mound he’d created gave way, covering him in an avalanche of sand. He was pronounced dead after his comrades pulled him from the debris.4

After a year of hard labor, the area was ready to be graded in December 1907. The city allotted $1,000 so that “the unemployed” and a number of horses could level the pit floor.5 The effort was divided into three-day contracts. Men could submit their name into a pool of workers, with 30 to 50 men chosen for each 72-hour work period. Demand was so high that hopefuls were routinely turned away. More than 225 names were added to the waiting list.6 The city announced plans for three baseball diamonds, a swimming pool, a lawn tennis court and children’s playgrounds on site.7 Another year passed as men toiled in the Pits. By the end of 1908 the city removed the workhorse stables and prepared the park for public use. While grading work was still in progress, the city announced a new name and park designation. The Daily Star editorial board mocked the announcement as premature: “The Christie sandpits will now be called Willowvale Park,” the editors wrote. “But that willowvale nothing towards making them fit for playgrounds.”8

The name change never did stick. Before the grounds were even officially opened, a reader of the Globe submitted a condemnation. “Why change the name from what it has been for a generation?”9 he asked. Three years after the official name change, it was accepted in Toronto that “what is now known as Willowvale Park is far and wide known to youngsters as the Christie sandpits.”10 Two decades later, locals in the Annex, Harbord and Christie Street neighborhoods of Toronto were still calling the park “Christie Pits.”11 In 1983, the City of Toronto finally abandoned the Willowvale moniker and rechristened Christie Pits officially.

The Pits baseball grounds were completed in May 1909. The Senior City Amateur League hosted the first reported game there on one of three diamonds ready for play. A team calling themselves the Ideals beat a group of ballplayers known as the Centennials by a score of 16–9. The Adair brothers, identified only by their initials, “S” and “B,” served as the battery for the Ideals.12 Teams bearing the monikers Kent, St. Andrew’s, Harbord, and St. Peter’s, named for various schools, streets, and churches, played baseball and softball in the Pits. After the completion of the first season of ballgames, two local aldermen led debate over the quality of the grounds. Alderman Dunn expressed regret that more had not been done to improve the quality of grass and infield dirt. He requested an additional $5,000 so that the diamonds could reach their potential. Alderman McBride was blunt in his reply: “It is just a sandpit and we can’t spend that much.” The City Council voted down Dunn’s request for more funds.13 McBride, however, was wrong. Christie Pits would prove to be much more than just a sandpit.

SOFTBALL IN THE PITS

In the era before television, entertainment often required a journey. Torontonians living between the city’s two embracing rivers could travel by streetcar to theaters, arenas and newfangled movie houses. If the radio serial wasn’t enough to keep them home, car owners could motor their way into the downtown core and attend any number of spectacles. Circuses, professional sporting events, and the last gasps of vaudeville were all enticing Toronto’s ticket buying public. Baseball was one of the greatest forces pulling people out of their homes. Maple Leaf Stadium, home to Toronto’s professional ballclub starting in 1926, was not the only baseball hotspot that routinely drew crowds in excess of 10,000.

People flocked to Christie Pits to see games. They would then, as they do now, sit on blankets or place chairs on the most welcoming parts of the grassy slope. The largest crowds turned up for senior men’s amateur baseball games, especially during playoff season. With multiple games happening simultaneously in the Pits, members of the crowd could shift from one diamond to another if their original game ended or became laborious. Games featuring men, women, and children, both baseball and softball, gained spectators as the days and evenings wore on. Big crowds were reported, but exact counts were hard to come by in the ticketless and seatless Pits. “Over 10,000”14 and “capacity attendance”15 were oft-reported attendances for various ballgames throughout the years. Charity softball matches, especially those featuring the National Hockey League Maple Leafs vs. the International League Maple Leaf baseball club, were highly attended events each year.16

By the end of the Roaring Twenties, at least 21 local softball organizations were recognized by the Toronto Amateur Softball Association.17 The TASA existed to collect fees, rent and allot diamonds, and ensure the amateurism of its softballers. The Exhibition League hosted games in the southwest, the Beaches League operated out east, while the Olympic, Intercounty, Danforth, and Elginton leagues all carved out their own sanctioned territories.18 The Playgrounds, Churches, and Western City leagues were the three TASA outfits operating in Christie Pits. The results of games and exploits of amateur softball players received consistent coverage in the Toronto Daily Star, a few column inches away from the professional baseball results. Even legendary sportswriter Lou Marsh, he of the formerly eponymous trophy awarded annually to Canada’s best athlete, devoted attention to softball and its many players. Great intrigue was added to the softball coverage in the early 1930s as the TASA sought to eliminate “shamateurism”19 and unaffiliated outlaw softball leagues20 from the diamonds of Toronto.

A reader of the sports page could also, at a glance, see the social fissures simmering in Toronto during the spring of 1933. Mixed in among the box scores, listed alongside softball teams called the Native Sons, Businessmen, Aces, Oaks, Lakesides, and Zion Benevolent, was a team in the TASA St. Clair League that had named themselves the Swastikas.21

ANTISEMITISM IN TORONTO

Owing to Canada’s deliberately Eurocentric immigration policies, the earliest Jewish immigrants to Toronto had been, for the most part, British subjects and merchants.22 At the turn of the twentieth century, the Jewish population in all of Canada was estimated to be just 16,401.23 That population remained small because the country’s immigration policy had always been as ethnically selective as it was economically self-serving. It entailed an unofficial descending order of ethnic preference, with Jewish and Black people at the bottom.24

The great majority of Jewish immigrants headed to large cities, where they rapidly formed an urban proletariat and began to fill crowded, often poverty-stricken neighborhoods in Winnipeg, Montreal, and Toronto.25 Toronto’s most prominent Jewish neighborhood could be found one block south of Christie Pits. The nearby Spadina Avenue garment industry employed many Jews who were excluded from other professions in the city.26 Numerous garment workers resided in homes north of Front Street, south of Harbord Street and west of Spadina.27 Harbord Collegiate Institute was the local high school. By 1919, there was a common belief among students that Jews and Italian Catholics were considered unwelcome in Christie Pits by the resident WASP majority.28

After the First World War, Toronto’s population was not immune to the concoction of anti-Semitic conspiracy theories and stereotypes infecting the Western world. “No Jews Allowed” and “Gentiles Only” signs could be seen hanging in the windows of restaurants, shops, and country clubs across the city.29 Ontario had practices in place known as Restrictive Covenants, which could prevent the sale of houses and property to anyone who was not Christian. The restrictions, struck down by the Supreme Court of Canada in 1948, were outlawed not because they were discriminatory, but because it was difficult to accurately assess the religion of potential buyers.30 Jews in Toronto were not just excluded from general society by their religion. They were also widely deemed to be a threat to that society.31

A pamphlet called The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, debunked as Russian propaganda by 1921, was widely read and considered responsible for the rapid rise of antisemitism in Canada. Available first at retailers and libraries, it was further disseminated when Henry Ford distributed 500,000 free copies across Canada and the United States via affiliated service stations and his network of auto dealerships.32 The Protocols presented itself as a record of meetings in which Jews from around the world plotted to subvert Christianity and gain world domination. By 1933, pro-Nazi pamphlets, some funded by the German party itself, were being distributed and read in Toronto. Both anti-Semitic and fascist groups formed in Ontario during that same year.33 So extensive was Canadian antisemitism that the American chargé d’affaires remarked on “the rapidity of its spread.” He informed his superiors in Washington that “Canadians had no desire to have Jews emigrate to their country” and that antisemitism was increasingly “finding expression in private conversations.”34 In 1930s Toronto, one did not need to be a devotee of fascism or Nazism to become suspect of Jews.35 Antisemitism was a common and accepted facet of everyday life.

On January 30, 1933, Adolf Hitler was appointed chancellor of Germany. His National Socialist German Workers Party won a minority government in the March 5 election. The German political scene was chaotic. Hitler consolidated support by framing his nationalist movement as a bulwark against Jews and communists. His speeches and statements were loaded with antisemitic untruths.

Hitler’s words and actions were closely followed by the daily papers in Canada. Within weeks of his selection, swastika clubs had formed and placed recruitment ads in Montreal and Toronto newspapers.36 These clubs espoused the political beliefs of their German inspiration. They placed antisemitism at the fore and used the new Nazi flag as their symbol. In April, shortly after Hitler issued the first of his more than 400 anti-Jewish laws and decrees, Andre Laurendeau became the first political figure in Canada to formally endorse the Nazi vision. He wrote in a Montreal newspaper that Jews constituted a social danger in Canada. His message was syndicated across the country.37 By the summer of 1933, Hitler and his policies were being widely discussed and debated on radio, in the newspapers, and on the streets of Toronto.38

The mere presence of Jews at areas of public recreation, including as softball spectators in the Pits, led to protests against Jewish use of public beaches and parks.39 The Balmy Beach Swastika Club was formed with the avowed intention of keeping Toronto’s largest beach free of “obnoxious visitors.” In early August 1933, the club paraded along Woodbine Avenue, 200 strong, with Nazi flags and “Hail Hitler” banners—a common representation of the slogan at that time, substituting the English word “hail” for “heil.” They said the symbol of the German Nazi party was for good luck, and would help their organization gain its objective. They sang as they marched: “Oh, give me a home, where the Gentiles may roam. Where the Jews are not rampant all day. Where seldom is heard, a lone Yiddish word. And the Gentiles are free all the day.”40

There were a few public voices directly condemning the swastika clubs. Jewish alderman—and future mayor—Nathan Phillips was the most prominent. “The whole principle is all wrong,” Phillips said. “I don’t think it will gain any prominence in an enlightened city like Toronto. This sort of rot simply won’t go.”41 Al Kaufmann, a Jewish resident from nearby Kew Gardens, formed an “up-town gang” to counter the swastikas. He and a number of Jewish youths marched the beach boardwalk looking for members of swastika clubs. “We couldn’t find any” he said. “If there had been trouble, I think we could have taken care of ourselves.”42

On August 2, 1933, the Daily Star ran a story with the headline “Feeling Tense.” It reported that for some time, “a real attempt at organizing a fascist movement aimed against the Jews has been in progress.”43 Evil that had been just below the surface was now in the open. The swastika banner that had been so prominently displayed at Balmy Beach would soon be unfurled during a softball game at Christie Pits.

HARBORD AND ST. PETER’S 1933 SOFTBALL CLUBS

St. Peter’s Church has stood at the corner of Bathurst and Bloor Streets in Toronto, six blocks east of Christie Pits, since 1907. It was expanded in 1925 to accommodate a growing number of Catholics in the area. The youth and young adult ministries at the church had been fielding softball teams in the TASA-affiliated Church League since games began in the Pits. By 1930, the St. Peter’s club had developed a reputation as speedsters. Nicknamed the “Galloping Ghosts,” they played a small ball brand of softball, winning games by virtue of their so-called snappy style.44 The team, in the Junior Division of the Church League, was also playing well defensively in 1933. Managed by William Carroll, St. Peter’s often allowed three or fewer runs45 and occasionally won games in a romp, such as their 11–146 drubbing of Westmoreland to cap the regular season.

By mid-August, St. Peter’s had successfully advanced through a series of playdown games. They were recognized by the TASA as champions of the Church League and scheduled to meet the winners of the Playgrounds League, with whom they shared the Pits.

The Playgrounds championship was decided during a best-of-three series played between teams representing Harbord Collegiate and North Toronto high schools. Harbord, coached by Bob Mackie, swept the series with a convincing 5–0 victory in Game Two. Sammy Brookes, the Harbord pitcher, was described as “sensational” by the Daily Star.47 Brookes had been involved in a game earlier that season when the free-hitting Harbord team smashed multiple home runs, including a grand slam, in a 24-run affair over a team from John Dunn Community Centre.48 The Harbord lads represented a school that first opened in 1892. It was a large and imposing Jacobethan Revivalist structure three blocks south of Christie Pits. Nearly 90% of its student population was Jewish.49

The Playgrounds and Church divisions of the TASA had produced their playoff teams for 1933. The citywide quarterfinal series was set to begin in Christie Pits on Monday evening, August 14. It would be a best-of-three showdown between the hard-hitting Jewish boys from Harbord and the speedy, small-ball Catholics of St. Peter’s. The religious affiliations of each team would overshadow their ballplaying abilities during the series. Five days before their first game, an omen appeared just beyond the left-field line.

A newly formed Willowvale Swastika Club paraded the Nazi banner down Bloor Street on Wednesday, August 9. Five Jewish men, residents of nearby Euclid Avenue, attacked the marchers, who retreated into the Pits. Sydney Adams, father of one of the Swastikas, dismissed the whole affair as “foolish nonsense and a lot of tomfoolery.”50

HARBORD VS. ST. PETER’S: THE RIOT AT CHRISTIE PITS

On August 14, over 11,000 people attached themselves to the steep sides of Christie Pits. Most of the crowd, described as one of the largest in the history of the park, came to see the Western City Baseball championship between the Vermonts and Native Sons.51 Several thousand spectators eventually crossed the pit to see the first game of the Harbord and St. Peter’s softball playoff.52 By this time, Harbord supporters had become aware of something more sinister in large crowds such as these. “Every time you went to watch a ballgame,” a Harbord fan later said, “these guys with swastikas would yell ‘Hail Hitler’ and all this.”53

The Toronto Telegram reported that a five-foot-long swastika banner, sewn in white cloth on a black sweater coat, was repeatedly unfurled by some St. Peter’s supporters whenever Harbord players came to bat. This continued throughout the game, “amid much wisecracking, cheering and yelling of pointed remarks.”54 The Harbord players managed to keep their cool, maintain their focus, and play well enough to tie the game in the bottom of the ninth inning. The top of the 10th saw no scoring, giving Harbord a chance to end it. Sensing their opportunity, the St. Peter’s supporters began flaunting their swastika banner. Shouts and epithets were hurled across the diamond as supporters of both teams found themselves on the verge of violence.

With a runner on second and animosities dangerously escalating, a Jewish boy came to the plate for Harbord. He looked not at the pitcher, but at the symbol of Nazi hatred being held aloft by his own countrymen. When the ball was nearly over the plate, he gripped his bat and swung it—not at the ball, but at them. He connected, hammering a double and winning the game for Harbord in dramatic fashion.55

Supporters of both teams filled the field as the players themselves retreated from the scene. Spectators, sure that a fight would follow, were surprised to see the two sides screaming at each other as they were pulled in separate directions.56 A young Jewish spectator told the Daily Star, “There will be trouble when the teams play here again on Wednesday evening.”57

Hours after Game One, during the early morning of August 15, members of the Willowvale Swastikas returned to the park with ladders, brushes, and white paint. On the roof of the communal clubhouse, in the center of Christie Pits, they painted a huge swastika above the words “Hail Hitler.” One of the painters was later found by a Daily Star reporter. Although he would not give his name, he admitted to the graffiti job and said, “We want to get the Jews out of the park.”58 William Carroll of St. Peter’s was eager to separate the actions of his supporters from those of his players. He stated that hoodlums beyond his control had started a sideshow. He then went on to defend those hoodlums: “Why should St. Peter’s supporters get the blame for it any more than the supporters of the Harbord team, or in fact, any other team in the park?”59

Game Two was scheduled for Wednesday, August 16. Two of Toronto’s daily newspapers printed warnings. The Mail and Empire quoted “Jewish boys” who said, “Just wait until the same teams meet again!”60 The Daily Star concluded its coverage of the painting incident by quoting a Harbord fan: “We won’t go to the next game to make trouble, but if anything happens, we will be there to support our players.”61 Another anonymous source told the paper that opposition to the swastikas would be more fearsome on Wednesday night.62

James Brinsmead, a municipal civil servant, visited the Ossington Avenue police station on Wednesday morning and informed constables there of the potential for violence. The police would eventually dispatch only a single officer to each of the two ballgames in the Pits that evening.63 Toronto’s chief of police, Dennis Draper, did not believe the second game of a softball series constituted a serious threat.64

It did not take long for a threat to materialize. Another “crowd of 10,000 citizens”65 was reported in Christie Pits. The western baseball final continued on the northeast diamond and the second Harbord vs. St. Peter’s game took place on the northwest softball field. Before the opening pitch of the softball game could be thrown, an altercation occurred between a member of the Swastikas and a Jewish spectator. The Swastika was hit in the head with a club while the spectator was thrown downhill into the cyclone fence of the backstop. Both men required medical attention.66

The first major incident of violence took place during the second inning. A group of Willowvale Swastikas approached an area of Christie Pits that was lined with 1,000 Jewish Harbord supporters. The Swastikas began to yell, “Hail Hitler” in unison. Incensed, a group of the Harbord supporters lunged at the chanters and told them to “shut up!” When the Swastikas persisted, a sawed-off lead pipe appeared and various members of the hate group were struck with it.67

A brawl ensued, with batons, more pipes, and other concealed weapons. Blood flowed freely as the fighters moved up the north hill towards Pendrith Avenue.68 They eventually brawled away from the Pits and found themselves fighting in nearby backyards. The softball game, which had paused to watch the fracas, resumed. The single police officer assigned to the neighboring baseball game ran across to support his softball associate. Order was temporarily restored.69

With the game tied after three innings, more cries of “Hail Hitler” rang out. Four Jewish youths drew sawed-off lead pipes and headed for two men they believed to be leading the Nazi sympathizers. Supporters rushed to the assistance of both groups of fighters.70 Three additional police officers, having arrived by motorcycle, joined the original patrol duo and helped defuse the skirmish.71 The atmosphere remained tense, but without incident, as St. Peter’s took a late lead. Harbord prepared for its final turn at bat in the ninth, down by a single run. It was not yet dusk as St. Peter’s secured a 6–5 victory by catching a deep fly ball from the last Harbord batter.72

As the crowd of thousands milled about after the game, two young men unfurled a large white blanket bearing a black swastika. In the words of the Daily Star, “a mild form of pandemonium broke loose,” and, as the Telegram put it, “The sign stood out like a red flag to a bull.”73 The antagonists bearing the flag were rushed by Jewish youths. One of the flag bearers was knocked out cold and another scurried away. The swastika flag itself was captured and torn in a pique of vengeful satisfaction by Walton Street resident Murray Krugle. What followed next was described as a “general inrush”74 of male youth who began to fight with fists, then with boots, and eventually with bottles, pipes, broomsticks, and baseball bats. The “Bloor Street War”75 was underway. The first bike pedalling recruiters feverishly cycled to adjacent neighborhoods pleading for reinforcements.

As word of the fighting spread, Jewish backup arrived by car and pickup truck from areas southeast of the Pits near Spadina Avenue. Next, carloads of Italian Catholics arrived from directly south of the Pits on College Street. The handful of police on site attempted to intercept the rolling cavalries, but they were quickly and badly outnumbered. Vehicles carried not only fighters but their weapons as well. A seven-foot-long piece of lumber with a spike driven through it was later found in an abandoned truck near the war zone.76

Brawling continued unabated for an hour before mounted and motorcycle police arrived. Their authority and presence did not immediately dissipate the rumble. The fighting merely tapered for another 90 minutes. Just before 10PM, the battle poured out of Christie Pits and onto Bloor Street as thousands of brawlers blocked the roadway. Streetcar bells and automobile horns added to the cacophony.77 Shortly after 10:30PM, the assembled police force was finally large enough to end the assaults.

The peace did not last. During the initial fighting, Joe Goldstein, a Jewish teenager, was chased across the Pits and knocked unconscious. He was carried first to the nearby home of his sister-in-law, and then by police escort to hospital. Goldstein was badly injured, but his wounds were not life threatening. Rumors began to spread around Jewish neighborhoods that Goldstein had died. Organization only took a few minutes, and soon, truckloads of shouting Jewish youths, armed with anything they could lay their hands on, were speeding back toward the softball grounds.78

Several of these trucks, each jammed with about 25 young men, were met by a column of police on horseback. The trucks broke through and soon found a large group of swastika-wearing enemies. The two groups attacked each other with black jacks, broom handles, stones, and steel and lead pipes.79 Hundreds of fighters who had already exhausted themselves and their original quarrels jumped right back into this new fray. The police were helpless. An eight-block section of Toronto—including one of its largest parks and downtown’s main northwestern thoroughfare—was lawless and out of control.

Both sides were accused of reckless irresponsibility during the riot. One eyewitness said he was horrified to see “a gentleman, passed middle age, who was taking no part in the violence, struck on the head with a baseball bat.” Joe Brown, a young witness to the fight, said he was walking home from the Pits when five youths jumped out of a passing car and assaulted him with clubs. A 21-year-old named Solly Osolky rushed in to help a fallen youngster on Bloor Street and was attacked for his efforts. “They belaboured me with their clubs,” he added. David Fischer had been a spectator at the ballgame. “I was preparing to go home,” he said. “Some fellow then hit me over the head and started to shout Hail Hitler.”80

Fighting continued in and around Christie Pits after 11:30PM. Injuries, fatigue, and a growing police presence began to divide the uprising into smaller and smaller battles. A crowd of rioters again blocked Bloor Street, causing the police to devise a new tactic. The motorcycle brigade would charge toward groups of fighters. When they were close enough to be effective, the officers would turn their exhaust pipes towards the combatants, spreading heavy, choking fumes throughout the crowd. By midnight, there were fewer than 200 people within 100 yards of the park. Occasional fistfights persisted. The police patrolled Christie Pits and the streets around the ball diamonds until the riot was officially declared over at 1:30AM, six hours after it started81.

Somewhat miraculously, no fatalities occurred during the riot at Christie Pits. Osolky, Brown, Fischer, Goldstein, and two men named Al Eckler and Louis Kotick were reported to have been the worst of the injured. They all suffered cuts, abrasions, and trauma about the head and neck. A few had broken bones. Most were released from hospital within a day. Undoubtedly, countless other street fighters kept their injuries to themselves.

Only two arrests were made during the riot. Russel Harris of Bloor Street was held on a charge of vagrancy, later dismissed. He’d been caught with a fishing knife. Magistrate Browne advised Harris to leave his knife at home unless he was scaling fish. Jack Roxborough was held on a charge of carrying offensive weapons. He’d been seen wielding a metal club above his head. He was given the option of paying a $50 fine or serving two months in jail.82 His decision has been lost to history.

Following the riot, Jack Turner, secretary of the TASA, announced that no more league games would be played in Christie Pits until the present trouble had been cleared up. The managers for both the Harbord and St. Peter’s teams denied responsibility for the riot and stated that none of their players had participated in the disturbance.83 Both teams would need to continue the series with new bats, owing to their equipment having been stolen and weaponized by the mob.

The TASA scheduled the third and final game in the series for Wednesday, August 23, at Conboy Soccer Stadium, an enclosed field with grandstand at the corner of Ossington and Dupont, about 12 blocks northwest of Christie Pits. The organization also announced that the game would be a ticketed affair. The TASA thought the cost of admission, and the park being a privately owned enclosure, would keep away the undesirables.84 A squad of police from the Ossington Avenue division surrounded the stadium and kept a strict watch on all points of entry. Police also forced a number of onlookers on a nearby rail bridge to vacate their unsanctioned seats. A few hundred others were said to have watched the game from nearby factory rooftops and household windows.85

Only 71 loyal spectators paid to see the rubber match at Conboy Stadium. It was described as one the finest exhibitions of softball ever witnessed in Toronto. The game went into the bottom of the 11th inning when “Red” Burke hit a walk-off home run to give the series to St. Peter’s by a score of 4–3.86 After losing a heartbreaking game, the Harbord team, “like true sportsmen, shook hands with the winners and wished them good luck in their future games.”87 St. Peter’s would go on to lose to a team known as the Millionaires, who were in turn bested by a team sponsored by the Cities Service oil and gas company (today known as Citgo). The Cities Service team claimed its trophy as Junior Softball Champions of Toronto during a ceremony held at the Royal York hotel on October 19, 1933.88

THE AFTERMATH

After the riot, the swastika symbol was cast in even darker shadow throughout Toronto. The Balmy Beach Swastika Club knew enough to abandon the symbol and change its name within 24 hours of the riot. At an emergency meeting, members were conciliatory, voting to allow Jews and gentiles to serve together on a new committee devoted to cleaning and protecting the beach.89 Other swastika clubs persisted but declined in favor and fidelity as the decade wore on. By 1936, Toronto’s newspapers were free of their mention.

Toronto Mayor William Stewart met the media a few hours after police had regained control of Christie Pits. He warned all citizens that people displaying the swastika would be liable to prosecution. “The repeated and systematic disturbances in which the swastika emblem figures provocatively, must be investigated and dealt with firmly,” said the mayor. “The responsibility is now on the citizens to conduct themselves in a lawful manner.”90

Toronto Police made three more arrests related to the riot the following Friday. 17-year-old Jack Pippy, 18-year-old Charles Boustead, and 21-year-old Earl Perrin were charged with unlawful assembly. In the Crawford Street garage owned by Pippy’s parents, police found the white paint and paraphernalia used to smear the swastika on the Pits clubhouse.91

When senior baseball returned to Christie Pits two days after the riot, the police presence was noticeable inside the park. About 100 teenagers mingled in the vicinity of the Pits, many of whom were said to have weapons and pieces of pipe concealed inside their coats.92 Though police said the boys were looking for trouble, they found none as “calm prevailed in the swastika war zone.”93 Police claimed that most of the youth had been drawn to the park out of curiosity. Both Harbord and St. Peter’s continued to field teams in the Christie Pits softball league for decades to come. There were no further overt incidents of antisemitism involving the two teams.

On September 10, 1939, six years and 25 days after the riot, Canada declared war on Nazi Germany and its swastika flag. By 1945, more than 10% of Canada’s population had joined the army. Over 1.1 million Canadians suited up and shipped out. Toronto supplied 2,000 recruits within 48 hours of the declaration of war and over 70,000 more as the conflict endured.94 Given the high number and youthful demographic of the rioters in Christie Pits, it would be reasonable to assume that many answered the call of king and country. The economic realities of the area around the riot zone make it even more likely. More than 60 men who died fighting for Canada during the Second World War lived in the immediate vicinity of Christie Pits.95

In 2008, the city installed a permanent plaque near the Bloor Street entrance to Christie Pits. It reads in part, “On August 16, 1933, at the end of a playoff game for the Toronto junior softball championship, one of the city’s most violent ethnic clashes broke out in this park.”96 Joe Goldstein, the boy whose rumoured death reignited the riot, now 88 years old, was present for the plaque unveiling.97 Another living Jewish witness to the riot, who wished to remain anonymous, remembered that August night quite clearly.

“When we got to the Pits, it seemed to me that half of the Jews and half of the goyim of the city were there,” he recalled. “There were a lot of heads broken. There was a tremendous confrontation, and I would definitely say that we won. We were proud. I think for a week we were higher than a kite.”98

Notes

1 “Sand Eaters Are in Toronto,” Toronto Daily Star, June 5, 1906, 1.

2 “A Check on the Proposed Civic Park in Sand Pits,” Toronto Daily Star, December 8, 1905, 6.

3 “City Buys Sandpits,” Toronto Daily Star, November 13, 1906, 1.

4 “Met Death Under Cave-In of Sand,” Toronto Daily Star, July 18, 1907, 8.

5 “For the Unemployed,” Toronto Daily Star, December 10, 1907, 9.

6 “Three Days Work for Only 225 Men,” Toronto Daily Star, December 11, 1907, 1.

7 “City Hall Comment,” Toronto Daily Star, June 27, 1908, 9.

8 “Little of Everything,” Toronto Daily Star, October 3, 1908, 2.

9 “A Name Suggested for the Playground at Christie Street,” Globe (Toronto), July 4, 1908, 9.

10 “Garrison Creek Will Be No More,” Globe, April 7, 1911, 9.

11 Ted Staunton and Josh Rosen, The Good Fight, (Toronto: Scholastic Canada Ltd., 2021), 7.

12 “Amateur Baseball,” Toronto Daily Star, May 10, 1909, 9.

13 “In Willowvale Park,” Toronto Daily Star, April 22, 1910, 2.

14 “Native Sons Double Score on Pat Downing’s Vermonts,” Globe, August 15, 1933, 11.

15 “Benefit Game,” Toronto Daily Star, July 12, 1930, 11.

16 “Scribes to Convort Down at Sunnyside,” Toronto Daily Star, June 7, 1933, 11.

17 “Softball Scores,” Toronto Daily Star, July 10, 1930, 11.

18 “Softball Results,” Toronto Daily Star, July 12, 1930, 11.

19 “Shamateurism,” Toronto Daily Star, July 5, 1933, 16.

20 “Three Men Re-Enter Organized Softball,” Toronto Daily Star, April 26, 1933, 9.

21 “Softball Scores,” Toronto Daily Star, May 23, 1933, 10.

22 “Softball Scores,” May 23, 1933, 26

23 Ira Robinson, A History of Antisemitism in Canada (Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2015), 36.

24 Irving Abella, Harold Troper, None Is Too Many: Canada and the Jews of Europe 1933-1948 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1983), 5.

25 Robinson, 37.

26 “Antisemitism,” Ontario Jewish Archives. accessed March 8, 2023, https://www.ontariojewisharchives.org/Explore/Themed-Topics/Antisemitism.

27 Jamie Michaels, Doug Fedrau, Christie Pits, (Toronto: Dirty Water, 2019), 102.

28 Staunton, Rosen, 7.

29 “Antisemitism.”

30 “Antisemitism.”

31 Robinson, 64.

32 Robinson, 64.

33 Robinson, 94.

34 Abella, Troper, 51.

35 Robinson, 94.

36 Michaels, Fedrau, 62.

37 Robinson, 90.

38 Michaels, Fedrau, 34.

39 Robinson, 66.

40 “Swastika Emblems Vanish from Beach,” Toronto Daily Star, August 2, 1933, 11.

41 “Hint Beach Ban Part of Vast Propaganda,” Toronto Daily Star, August 2, 1933, 12.

42 “Swastika Emblems Vanish,” 11.

43 “Feeling Tense,” Toronto Daily Star, August 2, 1933, 12.

44 “St. Peter’s at Greenwood,” Toronto Daily Star, July 17, 1930, 11.

45 “Softball Scores,” Toronto Daily Star, June 23, 1933, 11.

46 “Softball Scores,” Toronto Daily Star, August 3, 1933, 11.

47 “Two Softball Titles Won in Playgrounds,” Toronto Daily Star, August 3, 1933, 13.

48 “Harbord Wins,” Toronto Daily Star, June 7, 1933, 12.

49 Marcus Gee, “Harbord Collegiate Celebrates 125 Years as Toronto’s Famous Immigrant Launching Pad,” Globe and Mail (Toronto), April 7, 2017, https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/toronto/harbord-collegiate-celebrates-125-years-as-torontos-famous-immigrantlaunching-pad/article34637778/.

50 Cyril Levitt, William Shaffir, The Riot At Christie Pits (Toronto: New Jewish Press, 2018), 118.

51 “Swastika Painted on Roof of Club,” Toronto Daily Star, August 15, 1933, 27.

52 “Native Sons Double Score,” 11.

53 Levitt, Shaffir, 117.

54 Levitt, Shaffir, 117.

55 “Trouble Narrowly Averted at Ballgame as Hitler Emblem Hoisted,” The Mail and Empire (Toronto), August 15. 1933, 1.

56 Levitt, Shaffir, 118.

57 “Swastika Painted on Roof of Club,” 27.

58 “Swastika Painted on Roof of Club,” 27.

59 Levitt, Shaffir, 119.

60 “Police Warned of Ball Riot,” Toronto Daily Star, August 17, 1933, 1.

61 Levitt, Shaffir, 119.

62 “Police Warned,” 1.

63 “Police Warned,” 1.

64 “Draper Admits Receiving Riot Warning,” Toronto Daily Star, August 17, 1933, 1.

65 “Six Hours of Rioting Follows Hitler Shout, Scores Hurt, Two Held,” Toronto Daily Star, August 17, 1933, 1.

66 Levitt, Shaffir, 119.

67 Levitt, Shaffir, 120.

68 “Six Hours of Rioting, Scores Are Injured,” Toronto Daily Star, August 17, 1933, 3.

69 “Six Hours of Rioting, Scores Are Injured,” 3.

70 Levitt, Shaffir, 121.

71 “Six Hours of Rioting, Scores Are Injured,” 3.

72 Levitt, Shaffir, 121.

73 Levitt, Shaffir, 121.

74 “Swastika Feud Battles in Toronto Injure 4,” Globe, August 17, 1933, 1.

75 “Swastika Feud Battles in Toronto Injure 4,” 1.

76 “Hail Hitler Is Youths’ Cry,” Globe, August 17, 1933, 2.

77 “Six Hours of Rioting, Scores Are Injured,” 3.

78 Levitt, Shaffir, 124.

79 “Six Hours of Rioting, Scores Are Injured,” 3.

80 “Six Hours of Rioting, Scores Are Injured,” 3.

81 Levitt, Shaffir, 127.

82 “Draper Admits Receiving Riot Warning,” 1.

83 Levitt, Shaffir, 133.

84 “On Again,” Toronto Daily Star, August 22, 1933, 10.

85 “Flare Up Possibility Draws Curious Crowd,” Globe, August 24, 1933, 10.

86 “Only 71 Spectators See Pete’s Triumph,” Toronto Daily Star, August 24, 1933, 16.

87 “Flare Up Possibility Draws Curious Crowd,” 10.

88 “Softball Champions Honoured at Banquet,” Globe, October 20, 1933, 8.

89 “New Organization Will Take Place of Swastika Club,” Globe, August 18, 1933, 9.

90 Levitt, Shaffir, 129.

91 “Police Question Other Members of Alleged Gang,” Globe, August 19, 1933, 1.

92 “Calm Prevails Again in Swastika War Zone,” Globe, August 18, 1933, 1.

93 “Thousands in Park Wait Watchfully,” Globe, August 18, 1933, 2.

94 Ian Miller, “Toronto’s Response to the Outbreak of War, 1939,” Canadian Military History, Vol 11, 2002, 10.

95 Patrick Chan, “Grief’s Geography,” Global News, November 4, 2013, https://globalnews.ca/news/932833/griefs-geography-mapping-torontonians-killed-three-wars/.

96 “Riot at Christie Pits,” Local Wiki, accessed on March 24, 2023, https://localwiki.org/toronto/Christie_Pits_Riot/_files/riot-at-christie-pits-heritage-toronto-2008-plaque.jpg/_info/.

97 “Riot at Christie Pits.”

98 Levitt, Shaffir, 129.