Special Excerpt: The Cool of the Evening

This article was written by Paula Kurman

This article was published in Spring 2023 Baseball Research Journal

Excerpted from The Cool of the Evening by Paula Kurman, to be published in the first quarter of 2024 by Rosetta Books.

Dear SABR members,

My beloved late husband, Jim Bouton, asked three things of me if I were to outlive him: to make sure his archives were well and safely placed, to donate his 1962 World Series ring to the Hall of Fame, and to write a book about him, based on notes he urged me to keep during the forty-two years we were together.

“Nobody knows me the way you do,” he’d say. And “Write that down,” he’d say when something funny or meaningful or extraordinary happened to us. “Memory fades. Contemporaneous notes are better.”

His archives are now part of the permanent collection at The Library of Congress in Washington DC. In 2022, I donated the World Series ring to the Hall of Fame. That was hard. I’d worn the ring every day for decades. Jim didn’t wear rings, “in case a game breaks out and I’m called in to pitch.” But the ring is safe now, and in the right place. A rightful place.

And I’ve just finished writing the book. I’ve called it The Cool of the Evening—a phrase borrowed from Johnny Sain, Jim’s favorite pitching coach. It’s subtitled “A Love Story.”

Writing the book was both painful and wonderful. It brought him back in living color and at the same time highlighted the excruciating loss. I was grateful for the years of notes, kept at his urging. The writing process helped me grieve. The pandemic gave me the solitude I needed to complete the book.

Rosetta Books will be the publisher and the anticipated release is the first quarter of 2024. What follows, therefore, represents the first public viewing of any part of the text. SABR has always been our favorite baseball world organization. It feels natural to me, therefore, that you are the first to see parts of it.

In friendship,

Paula Kurman, Ph.D.

(Mrs. Jim Bouton)

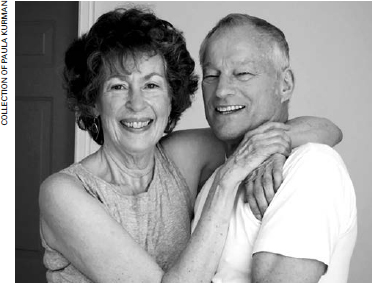

I am among the most fortunate of women. I loved Jim Bouton and was well and truly loved by him for more than four decades. It doesn’t get any better than that. I was his lover, his wife, his best friend, his playmate, his business partner, his confidante. We were each other’s editors, occasional critics and most appreciative audiences. He was my North Star, and I was his.

* * *

Baseball was Jim’s metaphor, all through his life. If things were going well, he’d make great plays in his dreams. His knuckleball would be working, his motion intact. If he were struggling with something in real life, his dreams would reflect his struggle. He’d have trouble making the team, or getting into the rotation, or finding his glove.

These were active dreams, which made them a little risky for me. I was usually okay when he was throwing. Since he wouldn’t sleep on his throwing arm, that arm was free to move, unencumbered. More dangerous were the times he was fielding the ball in his sleep. He was a fast, powerful runner and a great fielding pitcher—a good thing unless you happened to be sleeping in his path.

I don’t know what other couples discuss in moments of post-coital intimacy. It was during some of ours that I learned how to throw a knuckleball. Jim said it was a better choice than cigarettes.

* * *

So many men asked Jim wistfully over the years, “Don’t you miss it? Don’t you wish you were back in the Big Leagues?” He didn’t. Occasionally he’d re-read some of the stories he’d written in Ball Four and enjoy the memories, chuckling to himself. But Jim lived totally in the present. Wallowing in the past was not his thing.

He had no trophy room, no awards displayed, no visible plaques or scrapbooks. Everything was in boxes in the basement. We did have a couple of photographs of him in a Yankees uniform displayed only because I’d gone to the basement looking for something else. While I was rummaging through the boxes I found a loose pile of photographs I hadn’t seen before.

“What’s this?” I asked, about a photo of a trio in a group hug, smiling broadly.

“That’s me with Mickey and Yogi after a big win.”

“Hmm. Probably shouldn’t be loose in a box like this.”

“Probably not.”

And there was another photo of his teammates pouring champagne over his head. I rescued that one, too. Had them both framed and hung them on the wall. That was the extent of the visible reminders of his professional baseball years in our home.

Jim spent no time wishing for the old glory days. But oh, he loved the game itself. Not to watch on TV, or to sit in the stands. We almost never went to professional games. He wanted to play, to run in the sunshine, to throw a ball—to take his trusty old glove, suit up, and join a group of guys similarly obsessed. He wanted to work on his motion, get guys out with strategy and a dancing knuckleball. He had no interest in senior leagues, however, or what he called the “beer-belly league” of the Over 40s.

“They can still bat, many of them, but they can’t run. Where’s the challenge in striking out old men? And I can walk to first base before they even start running.”

So he’d join local teams of guys in their twenties and thirties—some of them having been up to the Bigs for a cup of coffee, others still dreaming about it. Real hardball played by strong young guys wielding aluminum bats.

“What’s it like for a former major leaguer to play amateur baseball?” Jim was frequently asked.

“I wouldn’t know. I don’t think of myself as a former anything,” Jim would say.

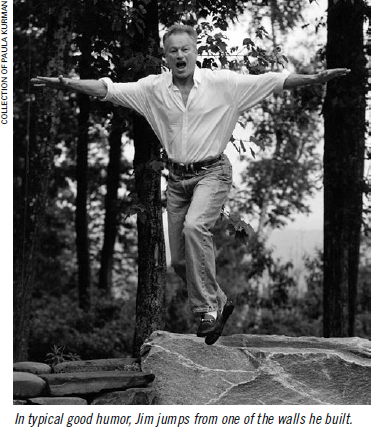

When we lived in New Jersey, he’d play for local teams there every year. When we moved to the Berkshires in Massachusetts, he was distracted for a while by the stone work he was doing for our new house. But he couldn’t leave baseball for long.

We never got around to finishing the basement, so there was all that unused space down there. Happily, there was enough footage between a makeshift pitcher’s mound (a taped-for-traction facsimile outlined on the floor) and a strike zone (outlined in black electrical tape on a wall sixty feet and six inches away).

Lining both sides of the corridor between the “mound” and the target were pieces of sheetrock and bits of lumber from the house construction. This insured that the ball, ricocheting back from the “strike zone,” would head straight back to Jim, saving it from getting lost in the jumble of cartons and uncategorized junk in the rest of the basement. It wasn’t pretty, but it worked.

Jim was working on his pitching skills to be competitive for the historic Saugerties Dutchmen in the Hudson Valley and for a team called Mama’s Pizza in the Albany Twilight League—named for the time of day the games were played, not the age of the players. Jim was in his late fifties, then, and in great shape.

Early every morning he would quietly and considerately tiptoe out of the bedroom, then thunder down the stairs to the basement, pick up a hard rubber practice ball and his trusty glove, and step onto the taped-on-the-floor mound for twenty minutes of hard, concentrated throwing. Loud impact sounds would resonate upstairs in our bedroom as the ball hit the concrete wall directly under me. My head still buried in the pillow, I’d laugh to myself. All that care to leave the room quietly, and now Mr. Thunderfootdownthestairs was pounding the hell out of the wall under the bed with his best shots, completely unaware of the sound transmission.

The throwing would go on for twenty minutes, after which he’d thunder back up the stairs, then tip toe softly back into the bedroom and, seeing that I was awake, pick up his weights for another fifteen minutes of upper body strengthening. No talking. Heavy breathing. Eyes internally focused. I’d get up and head for the shower. While I was toweling off, he’d come into the bathroom, sweating profusely, a look of triumph on his face.

“Babe, I haven’t thrown this well in years,” he’d say, “not even during my comeback! I’m getting my old motion back, getting down real low, my legs are strong!”

This would be accompanied by demonstrations. Fortunately, the bathroom in our new house was large enough to accommodate the activity.

“How wonderful were you this morning?” I’d ask him affectionately.

Would I have been a better wife if I had said to him, get real, you’re not a young man anymore, stop wasting your time? We were a lot closer to sixty than fifty. If it had been 1896, we’d have been old, maybe already dead. But in 1996 we were healthy, active, working for ourselves, learning new skills.

Besides, I was in no position to discourage him. I took up jazz dancing at forty-seven, began serious ballet training at fifty. I averaged three ballet classes a week until I was sixty-five, when a freak accident and hip surgery forced me to switch to ballroom dancing.

Jim was trying to find his lost motion, that intricate aggregate of muscular contractions, releases and rhythms that propel a knuckleball, spin-less, through the air, deceptively innocent, until at the last moment it flutters and hiccups on a stray air current, unmanning the batter and causing him to swing helplessly at the ball that is no longer there.

No, I never discouraged him. Jim was always in serious training for whatever baseball goal he was working toward. It lit him up, energized him. I loved his focused intensity. No one was more appealing than Jim when he was having a good time. It didn’t matter if he didn’t reach it, whatever the goal was. We both understood that all the benefits were in the journey.

In some games he was astonishingly effective, others not so much. Jim was a thinking pitcher, an intelligent strategist, and a scrappy fielder. Lean and fit, with the instinctive, lifelong understanding of a ball’s trajectory that never faded, he’d put 150% of his effort into limiting the damage of a hit ball.

He was also just one of the guys on the bench. No airs, no pulling rank, just camaraderie and a shared love of the game. He just wanted to be one of them. He played competitively into his sixties.

I loved those local games. Every time I watched him lope out to the mound, silently and confidently point his fielders to preferred positions as he took the measure of each batter he faced, I fell in love with him all over again.

* * *

On a trip to Italy in 2004, we went to Florence to see Michelangelo’s David. Postcards don’t do it justice. In the flesh—or rather, the original marble—it’s awe inspiring, overwhelming. Its beauty brought me to tears.

And there was something strangely familiar about it.

“Look, Babe, it’s you!” I said, to the amusement of some nearby tourists.

But it was. Not just the lean, masculine beauty of the figure, but that recognizable pose. There was the focused gaze in one direction, the body turned to one side, the throwing hand down and somewhat behind, the stone cradled in the hand, the weight on the back foot, the front foot slightly ahead in the direction of that focused gaze, the left hand loosely holding the slingshot against the left shoulder. Relaxed, but alert and focused.

Replace the stone with a ball and the slingshot with a glove, and there it is. Perfect.

* * *

I remember the game that would be his last in the semi-pro or Twilight League he’d been playing in for years. I had gone with him, as I usually did when the game was being played a fair driving distance from home. He was more tired at the end of a game now, and I was concerned about his ability to drive home safely if the field wasn’t local.

He’d begun to develop a pattern of getting off to a rocky start in the first inning, and then hitting his stride in the second inning. I’d hold my breath, wondering if he’d be able to recover. And then I’d see his body find its rhythm, and I’d relax. Somewhat.

On this day, his first inning on the mound was particularly poor, saved in part by some good fielding from his teammates. He got back into the dugout, and I didn’t like the way he was sitting. His usual body behavior—catching his breath, toweling off, fussing with equipment, focusing intently on the other team’s pitcher—was not in evidence. There was something wrong.

I watched him intently, and when he got up for the second inning, I was sure. He half-walked, half-loped to the mound. There was no energy in it. His chest heaved a few times. Not a good sign. He studied the ball in his hand. I felt so helpless. All I could do was watch.

There was no recovery in that second inning. A couple of men got on base who shouldn’t have, and Jim signaled for the manager to come out to the mound. The conversation only took a minute. Jim took himself out of the game and went back to the dugout. As he sat on the bench, he seemed to deflate. My heart broke for him. But there were protocols. I could not run over and put my arms around him. Not until he left that bench. Not till we were out of sight of the other players.

I no longer remember the end of that game, or precisely when Jim felt it was appropriate to leave. I don’t know how long I sat and watched him. But when he picked up his equipment bag I went to meet him and we headed towards our car. He put the bag on the back seat and got in on the passenger side. I got in next to him and took his hand, waiting for him to tell me.

“It’s over, Babe. It’s all over. Not just a bad day. I could feel it in my body. I can’t do it anymore.”

“I know, sweetheart. I saw it end.”

For the rest of that week he worked on building his stone walls. It soothed him—the craftsmanship, the hard physical work, the evidence of an area of remaining mastery. He didn’t go down to the basement to throw the ball against the wall. Or do his regular workout with his weights. He was quiet and thoughtful.

The following weekend I was sitting on the porch reading when I heard him leave his office and go down to the basement. A few minutes later he hurried up the stairs calling for me. There was an urgency in his voice.

“Babe? Where are you?”

“Out here on the porch…”

He rushed out, sat next to me, put his arms around me, and started to cry.

“I went down there to put some things away and I saw my glove and ball, just sitting there, waiting for me to play with them—they’re like my old friends, they were just sitting there—I know it’s silly…”

I hugged him tightly.

“Not silly at all—of course you’re upset. Throwing a ball has been a major part of who you are, how you know yourself—your whole life. To come to the end of that—it would be strange if you weren’t upset.”

We sat for a while and held each other.

“I only feel safe enough to cry when you’re with me,” he said.

“I’m always with you, Babe.”

* * *

August, 2012—Jim has a stroke that damages the language center of his brain. He recovers significantly, but not completely.

March, 2016—After noticeable decline, a differential diagnosis is made. Jim has CAA (cerebral amyloid angiopathy), a rare form of vascular dementia. It’s progressive and there is no cure.

* * *

Way back when we were first together, Jim had talked about his friend and editor, Lenny Shecter, who died of cancer in early middle age. Jim admired Lenny’s refusal to tell anybody about his illness.

“Why is that a good thing?” I’d asked Jim.

“Because he didn’t want anybody feeling sorry for him.”

“But he also denied friends and family the chance to be helpful and supportive. And as he changed, the people who loved him were probably confused by what they were observing. I don’t get how that’s a good thing.”

“Well, I always admired him for it.”

And that’s where we left it. It was a point of dis agreement between us, respectfully acknowledged.

But now we needed to think about it again. Unlike Lenny, Jim was a public figure, regularly being interviewed—and he was having word scrambles, pronoun mixups, and mid-sentence blackouts. He had a great deal of trouble understanding compound questions. In the face of puzzling behavior, people get nervous and draw their own conclusions. Did we want reporters to think Jim was drinking? Did we want to cut him off entirely from contact with the media without explanation? How would that be interpreted? Would that just add to the mythology in some quarters that he was high-handed and arrogant?

Navigating the world when you’re injured involves managing other people’s anxieties. But Jim needed to feel comfortable with how we would decide to move forward from here. How much to say, and to whom. This was his call, not mine.

For the media, we agreed that for now the stroke was enough information. We also decided that I would participate in his interviews, helping only when necessary, and explaining why I was doing so. Jim was relieved by this plan. We worked well together in those situations, and with my presence as a backup he relaxed and did better.

Unpacking compound questions like this from re porters would be my biggest job:

“So, Jim, how did it feel to pitch against ______________, a Cy Young award winner, back in 19 ____, particularly in that tie game in Cleveland, when you were having a shaky start to the season, and so much was at stake, both for the team and for you personally?”

I kid you not; that’s how these radio guys talk. They’re so afraid you’re going to cut them off before they’ve finished with everything they want to say that it tumbles out like cooked spaghetti. A brain-injured person can’t make sense of it.

We’d been hoping for long plateaus and a slow decline. But a few months into 2017 it became apparent that we weren’t on a plateau but a steep slope. Going down. Jim’s difficulties were now increasingly obvious. We talked about how he was feeling.

He described himself as “resigned,” and when I asked him about the things he still enjoyed, he said “Not much. I can’t follow things fast enough—I spend most of the time keeping my mouth shut—it’s annoying.”

A few days later, Jim had one of his really good days. He was more “present,” more in focus, more responsive. I took the opportunity to bring up something I’d been thinking about.

“You know, Babe, I think we need to decide something here. People are going to start wondering what’s wrong. Why don’t we take control of the story right now? Tell it right. And tell it to the right person.”

“What are you suggesting?”

“Choose someone we trust in the media, and tell that one person about the cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Accurate and clear facts. And maybe going public will be helpful to other people who are in a similar situation.”

“Hmm,” he said, and thought for a minute. “Tyler Kepner.”

“Exactly,” I said. “I had the same thought.”

Tyler’s wonderful article, would appear in The New York Times on Sunday, July 2, 2017.

That same weekend, the Society for American Baseball Research was holding its annual convention in New York. Of all the baseball organizations we’d had contact with over the years, SABR was our favorite. Dedicated to historical research and analysis, its members are passionately turned on by facts and ferreting out new information about America’s pastime.

“Baseball Nerds,” Jim called them. “My people.”

“Mine, too,” I agreed.

John Thorn, our dear friend and Baseball Historian Extraordinaire, was deeply involved with the organization and had already asked Jim to participate in a panel discussion on that Saturday.

“Great,” we said in unison.

“John, there’ll be an article in the Times the next day about Jim’s vascular dementia,” I said. “I would have to be with Jim anyway—he has too many word scrambles now to do it alone—but I’d like to use the opportunity to explain CAA … make it our first public disclosure before the article appears. Would that be okay with you?”

John agreed.

I always feel so much better with openness. Secrecy is not my thing. Everybody leaks anyway. Thinking you can hide something is delusional; there are so many “tells.” We were going to open the windows fully at last, let the fresh air in. And Jim was now fully on board.

There were hundreds of people in attendance. I had forgotten that New Yorkers get their Sunday Times on Saturdays, so many of them had already seen Tyler’s article and the news would come as no surprise.

Jim was relaxed and happy and in his element. We sat on the dais with other panelists, and John Thorn was his graceful and commanding self as the moderator. He introduced me as the first speaker and I went to the podium. I talked a bit about how Jim and I had met, the differences in our backgrounds, my lack of exposure to sports, and I offhandedly mentioned that I was a Jewish girl who had grown up in Washington Heights in upper Manhattan.

At which point, Jim, with an exaggeratedly puzzled expression on his face, leaned into his microphone and said in his best Mel Brooks imitation, “You’re Jewish?”

There was raucous laughter and huge applause from the crowd. Relief, appreciation, even love, washed over us. He was still Jim, still their mischievous rascal, still hitting just the right note in just the right way. He might scramble and forget words, but there was his trademark sense of humor and his impeccable timing. He wasn’t gone. The rest of the discussion went smoothly. We were so used to finishing each other’s sentences anyway.

Not long after that significant weekend, we received a “Save the Date” notice from the New York Yankees, inviting Jim back to Old Timers Day coming up in 2018.

Well. How about that.

* * *

As his dementia deepened, Jim’s dreams became more vivid. One night, I was awakened from a deep sleep by his erratic movements. He had reached over me and with his left hand was pounding the bed in front of me, frantically searching for something.

“What is it? Babe? What are you doing?” I was barely awake and he was scaring me.

“The ball! The ball! Where is it?” he shouted.

“There’s no ball, Babe, no ball…. you’re dreaming. Shhh, it’s okay, just a dream, there’s no ball…. Go back to sleep, sweetheart.”

He turned over and settled himself, still not awake.

“I coulda had that ball,” he grumbled accusingly.

Even dementia has its funny moments.

* * *

The Yankees followed up their Save the Date notice with an official invitation to Old Timers Day, clearly responding to Tyler Kepner’s article in the Times and the MLB.com reporting on the SABR conference.

“What do you think, Babe? Do you want to go?” I asked him.

A momentary pause. Then, “Sure. Why not?”

It would be far more complicated than that first time in 1998. Back then, a year after [daughter] Laurie had died, the Yankees responded to a Father’s Day letter that [her brother] Michael had written to the newspaper, asking the Yankees to let “bygones be bygones” and invite his father back into the fold to participate in his rightful place as a former Yankee. It had worked.

Jim had been ostracized for years by the baseball establishment for daring to expose the unfair labor practices in the industry in Ball Four. When they have to reach into their pockets, baseball executives have memories like elephants and hold grudges like the Hatfields and the McCoys.

In 1998, Jim was deeply grieving, but he was whole. He stepped out onto the field to a standing ovation from a sellout crowd. He even pitched an inning in the Old Timers Game and did well. But twenty years later, in 2018, he was very limited by the dementia. He couldn’t follow verbal instructions, couldn’t be left alone at any time, and was uneasy in unfamiliar surroundings. How would Jim manage in the locker room or find his way out onto the field when introduced? I certainly couldn’t be with him, but he navigated his world now by keeping me in sight. He did this so cleverly that even people who knew us weren’t aware of it.

I called the number on the invitation and spoke to the guy coordinating the event to describe the issues. He was very understanding and accommodating. I explained that I couldn’t manage the driving and care for Jim at the same time on the trip down and back without Edwin Castro, who aided me with caregiving. And that Jim would have to be accompanied to the locker room, guided through the tunnel to the field and pointed in the right direction when he was introduced. The Yankees agreed to it all, but said that Edwin would have to remain outside the locker room and wouldn’t be allowed on the field. That was fine, so long as the men were reconnected as soon as Jim was outside any protected area.

By the beginning of that 2018 baseball season, Jim was quite compromised. He didn’t look it from the outside, which was a help. Thinner by far and a little vague at times, but still moving normally, if a little un certainly. Only those of us who were close to him knew how bad it already was.

I ordered a bunch of tickets for family and friends. Again, the Yankee office graciously accommodated when I asked for our block of seats to be close enough and in direct view of where Jim would be standing on the field. I wanted him to be able to see us waving.

This would be the very first time any of our grand children would be seeing their Grandpa in uniform and on the field at Yankee Stadium. None of them had been born yet in 1998. Even if the youngest of them didn’t totally get the full impact of this occasion, it was important to the rest of us. We knew it would be the last time, and we wanted all six of them to be there.

The Yankees had planned a weekend of events for the players that included signing autographs for fans at the stadium Saturday afternoon, dinner for the players and their families Saturday night, and the game on Sunday. Would Jim be able to handle three days away from home? A strange hotel room, crowds, the bustle of the city, none of the routines he depended on for security? It was a gamble.

I included tickets for Edwin and his family. Again, the Yankees showed their kindness by offering hotel accommodations for them. Edwin rented a van, big enough for all of us and our luggage, and on that Fri day we set off on this adventure together.

Old Timers Day was a familiar concept to Jim and he was with people he trusted completely, so he was cheerful on the drive down, even whistling from time to time. Once in the city heading downtown on Park Avenue, he began to get a little anxious, peering out the window and twisting around in his seat.

“I think we’re going in the wrong direction,” he said. “Yankee Stadium is back that way,” pointing be hind us.

“You’re right, Babe,” I said, “Yankee Stadium is back that way, but first we have to check into the hotel. You’ll see. We won’t be at the stadium until to morrow.”

But “tomorrow” was one of those concepts he no longer understood. Or any other aspect of time-be fore, after, later, soon-all just words that mushed together for him.

He got quiet. But I could read his face. He under stood that he was missing something here, and so he’d better just say nothing and pay close attention until he could figure it out. It was how he handled his diminished understanding. It was smart. And effective.

That’s the hell of dementia. There is reasoning still in place, an intellect still functioning, even memories, but the “potholes” that develop in the brain as the dis ease progresses take the sense out of it.

He watched my face carefully, as he always did. If I looked relaxed, then he felt safe. He’d ride with it.

The hotel lobby was a chaotic mix of arriving players, their families, and a horde of fans looking for autographs as the players checked in. I was nervous about Jim’s ability to handle the sensory overload, but he began to recognize this scene as something he’d lived through many times before. And he recognized some of the players in the crowd. So he was tentative, but not frightened.

The most obvious sign that Jim was uneasy was that he stopped eating. He had nothing at dinner. The fol lowing morning I ordered his favorite away-from-home breakfast-bacon, and eggs over easy. He pushed it around on his plate.

On Saturday Jim and I got on the team bus with the other players, heading up to the stadium for a Meet & Greet with ardent Yankee fans.

“You see, Babe, now we’re heading in the right direction to Yankee Stadium.”

“Will my uniform be there?”

“Yes, but that’s for tomorrow. Today you’re just going to shake hands with a lot of fans and sign auto graphs, so you won’t need your uniform today.”

Jim retreated into silence, trying to process what I’d just told him. But when another player greeted him or reached out to shake hands, he responded in kind, and cheerfully. He still had all the social niceties.

He didn’t eat lunch. At the party for the players later that evening, the buffet table was loaded with interesting choices. But although I brought plate after plate to him, he wouldn’t touch any of it. This wasn’t home. He was alert and guarded, trying to figure things out. It must have been exhausting. At least he was drinking water.

Sunday morning. Jim picked at his breakfast; lost interest quickly.

Afterward, the players were to go onto the team bus and head to the stadium. Another couple of buses were designated for the families and guests of the players, but I would follow in our rented van with the Castros—except for Edwin—so that we could leave for home directly from Yankee Stadium at the end of the day. As was prearranged with the Yankees, Edwin would go on the team bus with Jim.

Jim looked uncertain as he began to understand that I would not be getting on this bus with him. Edwin put his hand companionably on Jim’s shoulder and said cheerfully, “We got this,” his familiar comment whenever the two of them set off somewhere together. The rest of us watched them get on.

“We’ll see you at the stadium!” we said, and moved briskly to the van, which was positioned be hind the bus.

It was a bright, sunny day, quite warm. When we got to the stadium, we found our section and settled in. Family and friends began to arrive. I was strung so tightly I practically twanged.

The day’s scheduled game and Old Timer introductions were sparsely attended that year. Not at all like the full house of 1998. I’m not sure why. Perhaps the team the Yankees were playing that day was not a favorite competition for the fans. Didn’t matter. I had only one focus anyway.

The ceremonies began and I took a deep breath. When I heard Jim’s name announced, I saw him lope out onto the field, guided subtly by Edwin’s presence at his side. I was surprised to see that they’d let him go out with Jim. They must have made the decision after evaluating the need themselves. Edwin came off the field as soon as Jim reached the other old-timers and began shaking hands. He was still good with non verbal cues. I could see that he was comfortable now as the other players reached out to him. They all knew about his illness, of course. Everyone was so kind. I let out the breath I’d been holding.

To my complete astonishment, that outgoing breath morphed into convulsive sobs. I covered my face and tried to stop, but I had no control over it. I was embarrassed.

“Sorry, I’m so sorry,” I said, worried about the impact of this breakdown on the grandchildren who lined the row directly in front of me.

“Don’t be sorry, Grandma,” Georgia said, reaching back and patting my knee with the maturity of a very recent high school graduate. Aspen patted my other knee, and Annabel took my hand and held it quietly until I calmed down. Skyler shot me a concerned glance, as did the two youngest, Alex, then nine, and Jack, seven. But they took it in stride. Nobody needed to have the reason for the breakdown explained.

The ceremonies ended, and the Old Timers who could still lope, loped off the field. The plan was to have Jim change out of his uniform into street clothes and join our group in the stands. In about twenty minutes the two men appeared at the top of the aisle in our section, Jim looking cheerful and tired, Edwin with the grin of a Cheshire Cat. Cellphone pictures of Edwin’s presence on the field at Yankee Stadium had already made their way back to his family in Colombia.

There was a lot of hugging all around, and finally Jim settled into a seat with a contented sigh.

“Get this man a hot dog!” I said to no one in particular, my arm around Jim’s shoulders—and it was done. Gratefully, I watched him take a bite of food.

At last.

We didn’t stay to see the regularly scheduled game. We were exhausted and we still had a three hour drive ahead of us.

It was good to get home. Jim sighed happily as we walked in the door.

“Sanctuary,” he said.

We slept soundly.

The next morning, another day of sunshine, we were having breakfast on our screened porch. The hummingbirds were feasting on our dahlias; an occasional breeze flirted with the leaves of the surrounding trees.

Jim was looking thoughtful. His eyes were clear and focused.

“How do you feel, sweetheart?” I asked him.

“I feel fulfilled,” he said.

“Really. How do you mean, ‘fulfilled’?”

“I feel like I finally belong, I’m part of it, part of them—where I always wanted to be. And you were accepted, too, by the other wives, and by the players. It was different this time. They all wanted to talk to you. The players wanted to know what you thought of things…I felt so proud to be with you…”

He went on like that for several minutes, to my astonishment. He was clear, coherent and deeply moved. And he was accurate. Not only about his memories of the weekend, but his profound understanding of the meaning of events, the changes in people’s behavior toward him.

He had always been somewhat cavalier about his ostracism by the baseball establishment. I truly believed that unless someone asked him about it, he never gave it much mind space. And yet… He was clearly moved and gratified by the acceptance he felt that weekend. Whatever the motivation of the Yankees in their gracious hospitality and accommodation to our needs, it doesn’t matter. What matters is that they were gracious. The deed itself is what counts. That it brought peace to my beloved at the end of his life is something for which I will always be grateful.

In my mind’s eye, I can still see Jim sitting at break fast on that beautiful bright day, sounding like himself again. I think about that moment often.

PAULA KURMAN was a child actress, and as an adult was Professor of interpersonal communication at Hunter College, a private consultant to industry, a keynote speaker, an essayist, and a seminar leader. Dr. Kurman’s new book, a memoir called The Cool of the Evening: A Love Story, will be out in the first quarter of 2024, published by Rosetta Books, and will appear in hardcover, audio, and digital formats.