Sputtering Towards Respectability: Chicago’s Journey to the Big Leagues

This article was written by Brian McKenna

This article was published in The National Pastime: Baseball in Chicago (2015)

The city of Chicago, already a hub of growth, became more important in the mid-nineteenth century once the Erie Canal linked it with the east coast and rail lines extended their reach throughout the emerging nation.

The city of Chicago, already a hub of growth, became more important in the mid-nineteenth century once the Erie Canal linked it with the east coast and rail lines extended their reach throughout the emerging nation.

Still, by the definition of the time, Chicago was still a “western city.” Serious development of the area was impossible until the settlement of the Black Hawk War in 1833. 1 In significant matters—politics, business, social, and cultural—Chicago played catch-up with the deep-rooted and wealthy eastern cities.

This was also true in baseball, a sport becoming defined by the formal “New York” rules. Yet as quickly as it created itself, Chicago established its interest in the national game. Clubs were playing by the New York rules even earlier than eastern cities like Baltimore and Washington, D.C. But because of its location, Chicago did not join the sport’s formal organization, the National Association of Base Ball Players, until 1867.

This happened to be the year professionalism began to proliferate throughout baseball. Because of their willingness to compensate players, whether directly or indirectly, and because of the greater opportunities that could be found for players, eastern clubs fielded the best nines. In order to catch up, the west had to tap that resource—that is, lure the talent west.

The first club to do this was the Red Stockings of Cincinnati, who in 1869 experienced astonishing success: an incredible winning streak and a coast-to-coast barnstorming tour that transformed the sport. Chicago wanted a piece of that success, as well as the accolades befitting its place among the top cities of the nation. The road to respectability for Chicago baseball, however, was characterized by a start-stop nature rather than a smooth, flowing path.

In late 1869, Chicago interests sent agents east to lure top baseball talent. This process would be repeated as needed during much of the next decade. Several hiccups occurred along the way, including a harsh local press, interfering shareholders, and a ruinous fire that destroyed not only the city’s premier ballpark but also caused an absence of a top professional team in the city for two seasons. The successes were notable but fleeting. The early seasons were, in fact, stellar for the newly-formed White Stockings, but following the 1871 Chicago Fire, the club floundered and disbanded. A new club was formed the next year.

By 1875, the club’s new president, William Hulbert, had tolerated eastern dominance for too long and took matters into his own hands. He robbed the nation’s top club, Boston, of four of its top men, overthrew the existing National Association, and formed a new professional organization: the National League. Chicago won the first NL championship in 1876 and placed the city among the sport’s elite, a position it has never relinquished.

Baseball would, for many decades, feel the imprint of Chicago influences: Hulbert, Al Spalding, Ban Johnson, Charles Comiskey, Rube Foster, and Kenesaw Landis, to name a few.

THE EARLY YEARS

Baseball, or at least a form of it, was played in and around Chicago before the first rail lines arrived. 2 The city’s first formal baseball organization was the Union Club, probably an offshoot of the Union Cricket Club, which incorporated on August 12, 1856. 3 The Excelsior Club organized the following year but distinguished itself by immediately adopting the New York style of play. 4

Match play—pitting one club’s skills against another—kicked off July 7, 1858, when the Unions hosted the nearby community of Downers Grove. The cordial contest, won by the visitors, was followed by a round of gentlemanly speeches and a visit to the theater, with all combatants still proudly wearing their uniforms. 5 The meeting also sparked an immediate call for local clubs to convene and hash out a standard set of rules, which would form the basis of any future competition. A local reporter, anticipating that “some alteration is to be made as to the manner of playing,” outlined the New York rules, which had been garnering attention of late. 6 The convention, held July 21, resulted in the forming of the Chicago Base Ball Club and approving the adoption of the New York rules. 7

In August, the Unions formally challenged the Excelsiors on the grounds of the Prairie Cricket Club, using New York rules. The first contest took place on August 30 with the Excelsiors triumphing 17–11. 8 In a return match on September 13, the Excelsiors won again, 30–17. “Speech making, pleasant repartee, merry jokes, and singing” at the Union Park House followed the contest. The editors of the Chicago Press and Tribune were “glad to note the good feeling that was evinced by the members of each club on this occasion, and trust that our citizens will take more interest in this truly healthful and entertaining game.” 9

Several new clubs (the Olympics, Columbias, and Atlantics) heeded the call for 1859. The Excelsiors and Atlantics established themselves as the city’s premier clubs and battled for local bragging rights over the next decade. On Saturday, June 11, the two met before 500 spectators, many of them female. The Excelsiors again took the victory. The Atlantics claimed the rematch in July then eked out an 18–16 win in the rubber match in August to, in essence, claim the championship of the city.

Baseball fever took hold of Chicago in 1860 as more clubs organized and match play exploded. 10 Taking the losses of ’59 to heart, “The Excelsior forces are greatly strengthened this season by the ascension to their ranks of several prominent players, formerly of the Columbian Club.” 11 The Atlantics, however, again took the season series before the largest crowds in the city to date.

“ Chicago was a growing metropolis with more than 112,000 residents. It was a city bursting with physical development, economic growth, and political vitality. The Republican Party’s choice of Chicago for its national convention that year put the city on the political map and infused it with energy…on June 18 in Baltimore, [Chicago resident] Stephen A. Douglas won the nomination of his divided Democratic Party, and Chicagoans must have appreciated the unlikely scenario of two Illinois men battling for the nation’s highest office.” 12

Abraham Lincoln, known and respected in Chicago, was elected to the presidency in the fall and the country descended into civil war. With many Chicago-area ballplayers having enlisted, clubs went dormant and the sport floundered in the city until after the war. The only notable matches during the war were a little-followed city series between the Garden City and Osceola clubs in 1863, a series between Garden City and a Freeport, Illinois nine the same year, and some play in 1864 among the men of the nineteenth Illinois Infantry.

Many believe the Civil War to be the catalyst spreading baseball through the country. In fact, the war stymied the game’s growth to a threatening extent. Luckily, the lure of the sport and Americans’ thirst for exercise and recreation brought a renewal in 1865—that is, once Chicago had properly mourned the assassination of President Lincoln.

DRIVING TOWARD PROFESSIONALISM

Many prewar players moved on and a new breed took over in 1865. The proud Excelsiors and Atlantics regrouped in late summer along with new clubs like the Ogdens, Pacifics, and Pioneers. The season ended with a tournament at the Winnebago County Fair Grounds, but matters ended inauspiciously; the Excelsiors walked off the field in the deciding match after the umpire reversed a call after a plea by the challengers. 13

Many prewar players moved on and a new breed took over in 1865. The proud Excelsiors and Atlantics regrouped in late summer along with new clubs like the Ogdens, Pacifics, and Pioneers. The season ended with a tournament at the Winnebago County Fair Grounds, but matters ended inauspiciously; the Excelsiors walked off the field in the deciding match after the umpire reversed a call after a plea by the challengers. 13

The call in December 1865 to form the Northwestern Association of Base-Ball Players sparked the game’s revival in the middle west. The Atlantics, Excelsiors, and Pacifics of Chicago joined fellow clubs from Illinois and seven other states to promote the sport. 14 The fever was such that a game was even played on ice over the winter at the Washington Skating Park. 15

For the 1866 season, the Excelsiors added a recruit from the east: pitcher C. J. McNally. This proved effective as the club won both of the season’s major tournaments to claim the championship of the west. The tournaments were the biggest baseball events to date for western sportsmen. The Rockford tournament, held in late-June, attracted clubs from Detroit, Bloomington, Rockford, Milwaukee, and Freeport as well as Chicago’s Excelsiors and Atlantics. The Excelsiors took the honors—and the prize of a gold ball—as McNally won the key game over the soon-to-be famous Al Spalding of the Rockford Forest Citys.

The field at the Bloomington tournament in September was even more impressive, including “the Union and Empire clubs of St. Louis; the Olympics of Peoria; the Pacifics of Chicago; the Perseverance club of Ottawa; the Louisville and Olympic clubs of Louisville; the Cream Citys of Milwaukee; the Forest City and Empire clubs of Freeport; the Capitol club of Springfield; the Hardin club of Jacksonville, Ill.; two Quincy clubs; and the Excelsiors of Chicago. A feature of this tournament was a specially built amphitheatre (sic) designed to allow spectators to witness two games at once…Again the Excelsiors were victorious, taking the series in impressive style.” 16 The Excelsiors, the Champions of the West, finished the season 6–0 in match play.

Black clubs also formed in Chicago after the war. One such was the Blue Stockings, a group of hotel and restaurant employees. 17 This nine gained notoriety in August 1870 for taking a series with the Pink Stockings of Rockford. The following month, however, they were excluded by decree from the city amateur tournament. 18 Over the winter, some Blue Stockings hopped to the Uniques and the reinforced nine became the first black club in baseball history which, according to James Brunson, “established themselves regionally and nationally.”

After topping the Blue Stockings 39 – 5 to claim city supremacy, the Uniques played and beat a white nine, the Alerts, 17–16 on July 10, 1871 . Noting the oddness of the interracial game, the Chicago Tribune commented, “…Contestants were the Unique Club (colored) and the Alert (not as much so).” 19 The Uniques took off for the east at the end of the summer, stopping in Washington D.C., Baltimore, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, and Troy. They split a series with the strong Alerts of D.C. and Pythians of Philadelphia and topped the other clubs, claiming bragging rights as the champions of the West.

In 1867, the Amateurs, Atlantics, Eurekas, and Excelsiors of Chicago joined the eastern-based National Association of Base Ball Players. 20 The Excelsiors started the season well, taking a series over the Atlantics and topping the Rockfords twice to further strengthen their claim as the class of the region.

The most-anticipated event of the summer was the July arrival in Chicago of the Nationals of Washington, D.C., who were barnstorming during the sport’s first western tour. The Nationals even carried Harry Chadwick, baseball’s great chronicler, in tow. The Nationals were set to play Spalding’s Forest Citys of Rockford, the Excelsiors, and the Atlantics. In a bit of a stunner, Spalding topped the Nationals 29–23. This was the D.C. club’s only loss during the ten-game tour, which also took them to Columbus, Cincinnati, Louisville, Indianapolis, and St. Louis.

Chicago eagerly awaited the Nationals/Excelsiors matchup, anticipating victory since the Excelsiors had defeated the Forest Citys as recently as the beginning of the month. The Excelsiors, however, were embarrassed by the Nationals 49–4. The loss hurt not only the Excelsiors’ self-esteem but also their standing in local baseball circles as the club became the butt of many a joke.

Chicagoans could not stand the second-rate status held by the nation’s western cities, whether it was in politics, business, or baseball. The humiliating loss to the Nationals reverberated throughout the city and helped drive the actions of local sportsmen and supporters for much of the next decade. It also led directly to professionalism in Chicago.

Though officially “amateur,” the Excelsiors began recruiting top players from the east and west, offering high-paying jobs during the week in return for their skill and diligence on the ball field. For the latter part of the season, they brought in left fielder John Zeller 21 from the Mutuals of New York and a pitcher named Keenan from the Bloomingtons. Other alleged professionals with the Excelsiors in 1867 include Al Spalding, C. J. McNally, and Tom Foley. 22

With the new recruits, the Excelsiors breezed through a tournament in Decatur in September, whipping the Egyptians of Centralia 79–9, and a hand-picked team 44–6. 23 On October 5 in Chicago, Keenan and his sluggers handily topped the Detroits in a heavily-anticipated match. 24 In Detroit on the 19th, the Excelsiors brought in Al Spalding for a game to help Keenan and the club beat Detroit again 36–24. The Excelsiors finished the year 10–1; their only loss since the end of the war was the rout by the Nationals.

For 1868, the Excelsiors imported Harry Lex and James Hoyt from Philadelphia. 25 The club faltered out of the gate against stiff competition, however, suffering losses to the Forest Citys of Rockford, Athletics of Philadelphia, Atlantics of Brooklyn, and Buckeyes of Cincinnati. After the July 21 loss to the Buckeyes, the club imploded; several players jumped ship and the club weighed merging with another. The Chicago Tribune lambasted, “Chicago needs a representative club; an organization as great as her enterprise and wealth, one that will not allow the second rate clubs of every village in the Northwest to carry away the honors in base ball…The Excelsiors cannot fill the bill.” 26

Luckily, a major fundraising effort allowed the Excelsior club to hire the talent needed to win and showcase the nine. 27 After losing to the strong Unions of Morrisania on August 10, the Excelsiors hired New Yorkers Fred Treacey, Joe Simmons (a much-needed catcher), and Bill Lennon from Brooklyn. They then hit the road after a loss to Detroit and two wins over Buffalo and Cleveland clubs. They drew with Detroit in Detroit, lost to Harry Wright and his Red Stockings in Cincinnati, and topped three mediocre clubs in St. Louis. 28 But the new hirees and traveling costs proved to be too expensive and management folded the Excelsiors.

Amateur clubs met with meager success in Chicago in 1868 and 1869. The Atlantics disbanded as well, leaving the city little baseball to boast about. Another western club, though, soon took center stage in baseball circles, broadening the game’s appeal and reigniting Chicago’s pride as a western city and in its baseball.

The sport’s first openly-declared professional squad, Cincinnati’s Red Stockings, dominated baseball in 1869 in the west and east. This impelled Chicago to amass a squad of the best talent available regardless of cost. The amateur ideal surely wasn’t going to get Chicago what it so dearly craved—respect from and bragging rights over the east.

1870 29

Late in 1869, 48 Chicago businessmen met and formed the Chicago Base Ball Association, intending to develop a professional squad in the mold of the Red Stockings, one which could compete and defeat the best in the country. These men wanted not only to show their superiority over eastern nines but also to supplant the Red Stockings as the west’s dominant team. 30 Shares and honorary memberships were sold, at $25 and $10 respectively, raising more than $15,000.

This was baseball’s first stock venture; previously clubs had been social in nature, raising funds primarily through member fees. “The Chicago businessmen eliminated the dues-paying club membership, instead raising capital through the sale of stock. The joint-stock company was a familiar business model in the booming Chicago economy. This was the organizational model of the future. By 1876 all top professional clubs followed the pattern, which continues to this day.” 31

Tom Foley, a local billiards hall owner, was the team’s new business manager, overseeing day-to-day operations. Among his first assignments was to head east and sign players for the 1870 season. He went to Philadelphia and New York and even placed an ad in the New York Clipper in hopes of attracting some top players. 32

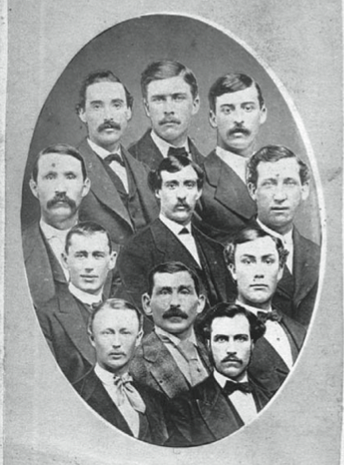

Foley’s efforts proved fruitful but expensive. Catcher Bill Craver was signed for $2,500. 33 Captain and second baseman Jimmy Wood was paid $2,000. Most of the others were paid between $1,500 and $2,000. Many of the players were taken from the Eckfords of Brooklyn, Unions of Lansingburgh (a.k.a. Haymakers of Troy), and Athletics of Philadelphia. The nine:

- Pitcher – Ed Pinkham (Eckfords), Levi Meyerle (Athletics) 34

- Catcher – Craver (Unions), Charles Hodes (Eckfords)

- First base – Bub McAtee (Unions)

- Second base – Jimmy Wood (Eckfords)

- Third base – Meyerle

- Shortstop – Ed Duffy (Eckfords)

- Outfield – Ned Cuthbert (Athletics), Fred Treacey (Eckfords), Clipper Flynn (Unions)

- Utility – Mart King (Unions)

This group became Chicago’s first professional nine. 35 Foley then sought a dedicated, enclosed ball grounds. The park was erected inside the oval of a race track at Dexter Park. A grandstand, with seating for 12,000 plus standing room, was built around the field. 36

With its grounds under construction, the club headed south for a series of games in St. Louis, Algiers (Louisiana), New Orleans, and Memphis. Despite suffering general malaise and intestinal troubles during the trip from drinking southern water, the Chicagos played to win. In one game, they smoked the Bluff Citys of Memphis by the outrageous score of 157–1. Memphis begged the Stockings to allow them to put some runs up, but Jimmy Wood would have none of it; his men would play hard no matter the score. 37

The Chicagos gained the nickname “White Stockings” by the time they took the field in St. Louis. “The Chicago nine were clad in their new uniform, which they had donned for the first time [in St. Louis]…It consisted of a blue cap adorned with a white star in the center, white flannel shirt, trimmed with blue and bearing the letter C upon the breast worked in blue. Pants of bright blue flannel, with white cord, and supporting a belt of blue and white; stockings of pure white British thread; shoes of white goat skin, with customary spikes, the ensemble constituting by far the showiest and handsomest uniform ever started by a base ball club.” 38

The dapper crew proved to be a strong nine; in fact, they won all 30 contests they played through July 2, although most of their opponents were second-rate. In mid-June, the White Stockings took off for an extended tour, their first, which saw them play strong squads from Cleveland, Buffalo, Rochester, Syracuse, Troy, Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Washington, D.C. They defeated the Eckfords and Unions—clubs they had previously decimated by signing their top players—but fell to the toughest eastern nines: the Atlantics of Brooklyn and twice to both the Mutuals of New York and Athletics of Philadelphia. They even dropped a game to Harvard and then lost another to the Unions.

In the eyes of the Chicago press, the tour had begun disastrously. Local sportswriters were extremely critical and the eastern ones condescending, especially after the White Stockings were buzzed 9–0 by the Mutuals on July 23. The term ‘Chicagoed’ (to be blanked) was born. Reeling from the criticism, stockholders began meddling in day-to-day affairs. Due to the travel and high salaries, the team stood $3,000 in debt by mid-August. Management reorganized and brought in Norman T. Gassette to take over the presidency. 39

Gassette demanded autonomy but gave Jimmy Wood and Tom Foley control over day-to-day team affairs without much interference. Bill Craver, alleged to have gambled and fixed games, was expelled from the club for violating his contract. 40

The White Stockings finished the season strong, arguably making them the best team in the country at season’s end. Henry Chadwick, as he was wont to do, claimed a piece of the success by declaring that the club’s fortunes turned around only after he gave Jimmy Wood a piece of advice: adopt a deader ball.

Dead ball or not, the White Stockings lost just once after August 5, pulling off some impressive road wins over the Atlantics, Athletics, Mutuals, Eckfords, and Red Stockings. After topping the Red Stockings in Cincinnati 10–6 on September 7, the White Stockings were greeted as conquering heroes by 3,000 fans at downtown Union Station. It had been a bit of a rocky season, but the win over their midwest rival healed all.

Excitement over an impending rematch electrified the city, and on October 13, 20,000 fans attended the game versus the Red Stockings at spacious Dexter Park. It may have been the biggest crowd in baseball history to that point. The White Stockings won again, 16–13, sparking celebrations and civic pride. In total, Chicago finished with a 65–8 record. Not even having the Mutuals storm off the field in protest in the ninth inning of the final game of the season on November 1 could dampen the club’s pride in its success.

Over the winter, Gassette laid out $4,000 of his own money to cover payroll and to sign new players. He also funded an eastern trip by Foley to lure new talent.

NATIONAL ASSOCIATION

That winter, a rift between amateur and professional players brought down the long-established National Association of Base Ball Players. Shortly after, in March 1871, the professional National Association was formed. The White Stockings immediately joined the new pro circuit, which is in effect a predecessor of the National League.

Also in March, Chicago’s city council granted the team use of a small plot of land on the lakefront. Dexter Park, on Halsted between 42 nd and 47 th Streets on what is now the city’s south side, was poorly located, too far from downtown.

The new property, however, was in poor shape, with piles of debris and trash scattered about. At a cost of $5,000, the club had a 7,500-seat facility erected. This, the first enclosed baseball-dedicated park in Chicago, would be known as White Stockings Grounds. The limited space led to necessarily quirky dimensions, which in 1871 included a short right field wall.

That season’s White Stockings featured holdovers King, McAtee, Treacey, Wood, and Duffy, with Wood and Tom Foley continuing to run day-to-day affairs. Joe Simmons, a former local Excelsior player, was obtained from Rockford and George Zettlein, a top eastern pitcher, was added from the Atlantics of Brooklyn.

The White Stockings were among the top clubs in the National Association, sitting near first place all season. Chicago’s last home game occurred on October 7, at which time they stood tied with the Athletics for the best winning average (.720, 18–7) in official contests. By the NA’s rules, however, Boston led the circuit with its 20 victories, albeit compiling “just” a .667 winning percentage. After returning from a hard-fought eastern trip and a win over the Boston Red Stockings on September 29, Gassette rewarded the men with expensive gifts, including a home for pitcher Zettlein. Then disaster struck.

On October 8, a fire ripped through Chicago; it raged for three days. The White Stockings’ ballpark was destroyed on October 9 along with the team’s adjoining business offices. Moreover, they lost their uniforms, equipment, record books, receipts, and on-hand cash. “The loss of the members of the nine was generally heavy, consisting of all their clothing and personal property. The only exceptions were Foley, Atwater, and Captain Wood, who all lived outside the limits of the fire.” 41

In despair, the White Stockings formally released all their players. The men regrouped in the east, though—save Atwater—to play some contests. Three of these games counted in the standings, including the championship. Two thousand spectators, a fair share of who were Chicagoans and Philadelphians, showed for the deciding contest, held at Union Grounds in Brooklyn. The Athletics won 4–1 to settle the matter. The men then scattered and the club folded for good.

In April 1872, Gassette and fifty others formed the new Chicago Base Ball Association with the immediate intention of erecting suitable grounds with which to entice top clubs to play in Chicago. Naturally, the long-term goal was to rebuild a top level club once again for Chicago. 42

The 23 rd Street Grounds opened at the end of May 1872 at a cost approaching $4,000. William A. Hulbert became a club director in July, his first official position with the club. 43 Baltimore, Cleveland, New York, Philadelphia, and Troy made the trip to Chicago during the summer to play at the new ballpark, and the project actually proved profitable, as the team finished the year about $400 in the black.

In August 1873, Gassette and Jimmy Wood hit the east coast to amass a nine for 1874. The effort proved successful and professional baseball returned to the Windy City.

The 1874 White Stockings included top names such as Jim Devlin, Davy Force, and Paul Hines. Former Chicago players Jimmy Wood, Ned Cuthbert, Levi Meyerle, George Zettlein, and Fred Treacey were on board. Wood was slated to captain the club once again, but while trying to lance an abscess on his left leg, he instead gashed his right leg badly enough to lead to infection and eventually amputation. 44 Wood did return in August as field manager, though.

While pro baseball was back in Chicago, the 1874 and 1875 White Stockings were of second-division quality. Sloppy play brought fan disillusionment and even an unfounded charge of game-fixing. In August 1874, William Hulbert assumed the day-to-day management of the club, a responsibility he maintained until his death in April 1882. That year, the White Stockings finished fifth in the eight-team organization with a 28–31 record.

Davy Force’s contract became an issue over the winter. He first re-signed with Chicago for 1875 and then inked a deal with the Athletics. At first, the National Association awarded him to Chicago, but after the organization installed a Philadelphia-based president, the decision was reversed. 45 An incensed Hulbert, feeling cheated perhaps with good cause, 46 would soon get his revenge.

BIRTH OF A NEW LEAGUE

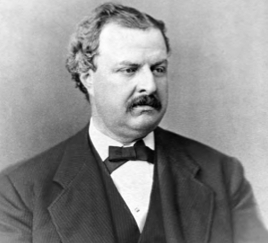

Hulbert, a grocer by trade, married the daughter of his employer, eventually taking over the company and expanding into the coal trade. He also held a prestigious and influential position on the Chicago Board of Trade. The 200-pound Hulbert was loud and authoritarian and usually got his own way.

The White Stockings disappointed in the standings in 1875 but had another good year financially. The National Association itself, however, had numerous troubles, including gambling, game-fixing, and excessive revolving (that is, players jumping clubs). That Boston copped each pennant from 1872 to 1875 riled Hulbert, and some others, to no end. Financial instability plagued the organization, which fielded too many clubs, especially in small markets. Expensive trips between the east and west and the travails of multiple unstable clubs in Philadelphia also taxed the business model.

Hulbert added to the NA’s woes by pulling an old Chicago trick: luring players from eastern clubs. During June 1875 he negotiated with and signed much of Boston’s roster for the 1876 Chicago White Stockings. Hulbert brought over Al Spalding, Cal McVey, Deacon White, and Ross Barnes. Spalding, the sport’s best pitcher, was the key component. Hulbert liked the fact that he was originally a western player and intelligent to boot. On June 26, Spalding, in turn, recruited Athletics players Cap Anson and Ezra Sutton, though Sutton later reneged.

The infighting and strain clouded the National Association all winter. Concerns existed that the players moving to Chicago could be expelled from the NA. In order to prevent this, and to usurp control from the east, Hulbert organized several western clubs and set out to form the new National League.

With the western clubs on board, he approached the eastern owners in February 1876. Hulbert extended an olive branch, offering the NL’s presidency to an eastern owner, Morgan Bulkeley of Hartford. It was clear to all, however, that Hulbert was the driving force behind the new endeavor.

It seems that the new departure was, from the first, a Chicago idea, and without desiring to detract from the good judgment of the club managers who came into it after it had been explained to them, it should go on record that the president of the Chicago Club is to be credited with having planned, engineered, and carried the most important reform since the history of the game, and the one which will do most to elevate it. 47

Baseball’s oldest league, the National League, kicked off two months later. Hulbert’s efforts paid immediate dividends as the White Stockings took the new organization’s first pennant, firmly planting Chicago as standard-bearer of the national game.

BRIAN McKENNA grew up and lives in Baltimore, not too far from the old Memorial Stadium. His upcoming work focuses on the beginning of the game in Baltimore, the 1860s.

Sources

Brunson, James Edward. The Early Image of Black Baseball: Race and Representation in the Popular Press, 1871-1890 . Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Company, 2009.

Chicago Daily Inter Ocean, 1874-1875

Chicago Press and Tribune, 1858-1860

Chicago Tribune, 1860-1876

Cleveland Herald, 1870

Freedman, Stephen. Journal of Sports History, “The Baseball Fad in Chicago, 1865-1870: An Exploration of the Role of Sports in the Nineteenth-Century City,” Summer 1978.

Hartford Courant, 1871

New York Clipper, 1870

New York Sun, 1869

New York World, 1874

Milwaukee Sentinel, 1870

Morris, Peter and others. Base Ball Pioneers, 1850-1871 . Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2012.

Ohio Democrat, New Philadelphia, 1870

Ohio City Derrick, Pennsylvania, 1870

Peterson, Todd . Baseball Research Journal, “ May the Best Man Win: Black Ball Championships,” Spring 2013.

Retrosheet.org

Smiley, Richard A., “The Life and Times of Norman T. Gassette,” prepared for SABR Nineteenth Century Committee conference, April 18, 2009

Sporting Life, October 28, 1885

Titusville Herald, Pennsylvania, 1871

Wisconsin State Journal, Madison, 1870

Wright, Marshall D. The National Association of Base Ball Players, 1857-1870 . Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2000.

Notes

1 Encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org

2 “There were well established teams throughout the state of Illinois as early as those of Chicago, if not earlier. Indeed, the Lockport Telegraph of August 6, 1851, tells of a game between the Hunkidoris of Joliet and the Sleepers of Lockport, that antedates anything similar for Chicago.” Federal Writers’ Project, Baseball in Old Chicago . (Illinois: Works Project Administration, 1939)

3 Peter Morris, Baseball Pioneers: 1850-1870, “Excelsiors of Chicago, Prewar.” (Jefferson, North Carolina and London: McFarland & Company Inc., 2012)

4 Chicago Daily Republican, August 17, 1865

5 Chicago Press and Tribune, July 8, 1858. Clubs of the early era generally corresponded with each other asking if the other would like to play a game. The offer and acceptance would then be made public in the form of a challenge. Thus, greater attendance and newspaper coverage followed. If a public notice wasn’t made, only word of mouth among participants, friends and family, in early 1858 or previous years, there in fact may have been match games that were not reported. The arrival of the Downer’s Grove club in town may have sparked this coverage, even if no public notice was given.

6 Chicago Press and Tribune, July 9, 1858. Inferring from this immediate call to standardize the rules, it seems to me that the Union club may have been a holdout on the New York rules. The local Excelsiors already played by the New York rules, which is why the reporter anticipated “some altercation” in the matter. At the meeting, the Unions agreed to the New York style. This probably had something to do with Downers Grove, or more specifically, to adopting rules complimentary with adjoining communities to ease future issues. On a larger scale, this process was repeated over and over until the New York rules came to dominate the baseball landscape throughout the nation.

7 Federal Writers’ Project, Baseball in Old Chicago . (Illinois: Works Project Administration, 1939) The Chicago Base Ball Club was not a ball club but rather a governing body for the sport in Chicago.

8 Chicago Press and Tribune, September 1, 1858

9 Chicago Press and Tribune, September 4, 1858

10 At least 14 clubs engaged in match play during the season.

11 Chicago Press and Tribune, August 24, 1860

12 Stacy Pratt McDermott, “ Base Balls and Ballots: The National Pastime and Illinois Politics during Abraham Lincoln’s Time.” (Thenationalpastimemuseum.com )

13 Peter Morris, Baseball Pioneers: 1850-1870, “Excelsiors of Chicago, Postwar.” (Jefferson, North Carolina and London: McFarland & Company Inc., 2012)

14 Chicago Tribune, December 7, 1865

15 Chicago Tribune, January 26, 1866

16 Federal Writers’ Project, Baseball in Old Chicago . (Illinois: Works Project Administration, 1939)

17 Other early black clubs included the Uniques, Oaklands, Red-Hots, Socials, and Gordons.)

18 Chicago Tribune, September 17, 1870

19 Chicago Tribune, July 11, 1871

20 In 1867, there were at least 45 amateur clubs in Chicago, a total that decreased over the next few years.

21 Zeller fractured his knee running the bases in August 1868, one of the worst accidents for a Chicago ballplayer during the era.

22 Chicago Tribune, December 30, 1877

23 Chicago Tribune, September 20 and 21, 1867

24 Chicago Tribune, October 6, 1867

25 Chicago Tribune, December 30, 1877

26 Chicago Tribune, July 22, 1868

27 Chicago Tribune, July 24 and 28, 1868

28 Peter Morris, Baseball Pioneers: 1850-1870, “Excelsiors of Chicago, Postwar.” (Jefferson, North Carolina and London: McFarland & Company Inc., 2012)

29 By 1870, more than 50 company clubs existed in Chicago; some companies fielded more than one nine.

30 Chicago Tribune, November 26, 1869

31 Richard Hershberger, Baseball Research Journal, “Chicago’s Role in Early Professional Baseball” (Phoenix, Arizona: Society for American Baseball Research, Spring 2011). Admission fees developed slowly in Chicago. Space was tight in the city and many of the ball lots couldn’t accommodate too many fans. Many games were played along the lakeshore or took place outside the city in the vast prairies that surrounded Chicago, especially in communities that naturally extended into the prairies. Admission fees first developed when many clubs came together for area tournaments, as by definition most of the clubs had traveling expenses to cover. The matches with the D.C. nine back in 1867 were specifically called a tournament so that fees could be collected.

32 Tom Foley is not to be confused with Chicago ballplayer Thomas James Foley who played with the Excelsiors in 1866-1868 and umpired in the National Association.

33 Craver was actually signed much later—well into 1870.

34 Here is a quote by John Thorn, at Our Game blog at MLB.com, discussing the earliest known existing professional contract : “At the Baseball Hall of Fame exists a contract between the new Chicagos and Levi Meyerle, formerly of the Athletic Club of Philadelphia. The two parties agreed that for one year, from February 15, 1870 through February 14, 1871, the player would receive $125 per month, for a total of $1500.”

35 Chicago Tribune, February 18, 1870

36 Chicago Tribune, May 27, 1870

37 Federal Writers’ Project, Baseball in Old Chicago . (Illinois: Works Project Administration, 1939)

38 Cleveland Herald, May 2, 1870. Jimmy Wood was entrusted with the selection of the team’s uniform design and colors.

39 Chicago Tribune, August 11, 1870

40 Daniel E. Ginsburg, The Fix Is In: A History of Baseball Gambling and Game-Fixing Scandals . (Jefferson, North Carolina and London: McFarland & Company, Inc., 1995) Craver would be expelled by the National League in 1877 on related charges.

41 Chicago Tribune, October 14, 1871

42 The displaced Foley ran a local semi-pro outfit in 1872 and 1873 with limited success.

43 Though, of course, the new White Stockings didn’t actually exist in 1872.

44 Chicago Tribune, July 11, 1874

45 Chicago Tribune, April 16, 1875

46 In all fairness, of course, the White Stockings had repeatedly taken players from eastern clubs.

47 Chicago Tribune, February 13, 1876. Interestingly, the baseball world didn’t seem to comprehend, when the Hall of Fame was established, the inner workings of the time. Bulkeley, the National League’s first president, who served only one year in the role, was inducted in 1937 to counterbalance the election of American League president Ban Johnson, a true giant of the game.