Standardized Peak WAR (SPW): A Fair Standard for Historical Comparison of Peak Value

This article was written by David J. Gordon

This article was published in Spring 2023 Baseball Research Journal

When judging the greatness of a baseball player’s career by whatever metrics one may put stock in, we weigh them from two perspectives:

1. Total Value: How much did they accomplish in their career? How many years did they play at a high level? What career milestones did they achieve?

2. Peak Value: How productive were they in their very best seasons? Were they ever regarded over any statistically meaningful time period as one of the top few players in MLB?

The most exalted players in the Hall of Fame (HoF)—Babe Ruth, Willie Mays, Ty Cobb, Walter John son, Hank Aaron, Rogers Hornsby, Honus Wagner, Cy Young, etc.—were elite on both counts; one need not overthink their HoF qualifications. But many less exalted players, both inside and outside of the HoF, were elite from one perspective but not the other. At the two extremes, we have “marathoners” like Don Sutton, who compiled elite career totals (324 W, 3,574 SO) in 23 seasons but never came close to winning a Cy Young award, and we have “sprinters” like Sandy Koufax, who won three Cy Young awards and an MVP award in four seasons (1963-66) but pitched only 12 seasons and won only 165 games. Both are worthy Hall of Famers, but they got there by very different paths.

Over the last two decades, the Wins Above Re placement metric (WAR), which combines the contributions of different performance elements, weighted according to their contributions to team wins and adjusted for the environment in which a player’s statistics were accrued, has become the metric of choice for global evaluation of player performance.1,2 WAR is superior to traditional counting stats like HR, RBI, W, and SO because it incorporates many diverse elements of performance that contribute to team wins and adjusts for the environment (league, ballpark, era) in which a given player performed. But while career WAR is a reasonable measure of the total value of a player’s accomplishments, we have not had a good measure of peak value.

Jay Jaffe invented a WAR-based composite score called the Jaffe WAR Score (JAWS), which purports to combine total and peak value into a single global performance metric to assess a player’s qualifications for the HoF.3,4 JAWS is the simple average of career WAR (the total value component) and the combined WAR (WAR7) for the player’s seven best seasons (the peak value component). The problem with this method is that WAR7 is a poor measure of peak value, especially for pitchers. While hitter usage has remained relatively constant since the advent of the 154-game schedule in the 1890s (with the notable exception of the Negro Leagues), seven seasons has a very different meaning for pitchers of different eras.

In the 1870s, teams played only 2-3 games per week, and 90% of the innings were handled by a single pitcher.5 Now, 150 years later, we have 13-man pitching staffs (not counting frequent call-ups of fresh arms from the minor leagues) with relief pitchers taking on an ever increasing share of the workload. Today, few individual pitchers accrue as many as 200 IP per season. So, the 11,633 batters faced (BF) by Cy Young in his best seven seasons is more than double the 5,752 BF by Clayton Kershaw in his best seven sea sons.6 In this context, Kershaw’s 47.7 WAR7 really represents a higher “peak” performance rate per 1,000 BF than Young’s 79.1 WAR7 (8.3 versus 6.8 WAR per 1,000 BF).7 As for relief pitchers, Mariano Rivera faced only 5103 batters in his entire career but still accrued 56.4 WAR—an even better production rate (11.1 WAR per 1000 BF) than Kershaw’s peak. However, comparing production rates over disparate numbers of BF is unfair to Cy Young, because this would require Young to maintain peak effectiveness over twice as many BF as Kershaw. We need a peak value measure that compares like numbers of BF for pitchers and like numbers of PA for hitters.

I will now present a new construct called Standardized Peak WAR (SPW), which is designed to compare peak values of players who received vastly differing annual PA or BF opportunities. SPW is standardized to 3,250 PA for batters and 5,000 BF for pitchers. The former number represents five 650-PA seasons for batters, 650 PA being a typical total for a healthy everyday player hitting near the top of the lineup over 150-160 games. The latter number represents five 1,000-BF seasons, where 1,000 BF represents a typical workload for a regular starting pitcher from 1909-88.8 In the 1880s, pitchers like Charles “Old Hoss” Radbourn, Pud Galvin, and Tim Keefe among others posted insanely high WAR totals (near 20) while amassing 600 + IP and 2500 + BF. Since 2006, only three pitchers—CC Sabathia (1,023 BF in 2008), Felix Hernandez (1,001 BF in 2010), and David Price (1,009 BF in 2014)—have logged as many as 1000 BF in a season. The detailed calculation of SPW and a comparison of rankings by WAR and SPW are presented below.

METHODOLOGY

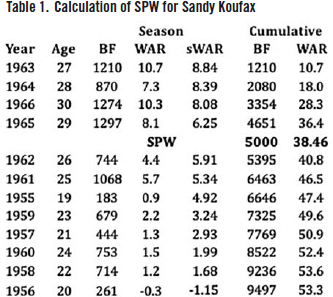

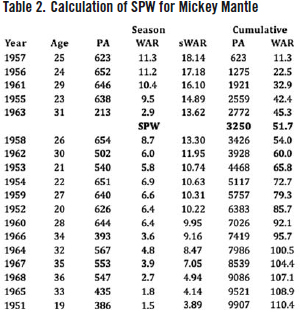

The Baseball-Reference.com version of WAR for pitchers and for non-pitchers as of December 2022 is the underlying performance metric used in the calculation of SPW.9 For Negro Leaguers, I have used the comparable WAR values from the Seamheads database, which incorporates statistics from both MLB-certified and uncertified leagues (and thus recognizes the achievements of players of color who played before 1920 and those who played mostly in Cuba and Mexico).10 I have calculated SPW for every player in the HoF and for every MLB player with career batting or pitching WAR ≥ 30. The calculation of SPW is illustrated below for two mid-20th century icons, Sandy Koufax (Table 1) and Mickey Mantle (Table 2).

One first calculates “standardized WAR” (sWAR) per 1000 BF for pitchers or per 650 PA for hitters for each season and sorts the seasons in descending order. Then one adds up the WAR for each season until reaching 5,000 cumulative BF or 3,250 cumulative PA. SPW is obtained by interpolating between the cumulative WAR values just before and just after the BF or PA threshold is crossed. For pitchers with <5,000 BF or non-pitchers with <3,250 PA, SPW is defined as their career WAR.

Note that the SPW construct cannot combine hit ting and pitching stats for a single player within any single season. For players with significant career value as both hitters and pitchers (e.g., Babe Ruth, Martin Dihigo, Bullet Rogan, Wes Ferrell), I have used the higher of their SPW for hitting and pitching.

One could as easily use the FanGraphs version of WAR or other similar metrics for this purpose.11 Indeed, a similar approach can be applied to any appropriate cumulative (as opposed to rate) stat.

RESULTS: PITCHERS

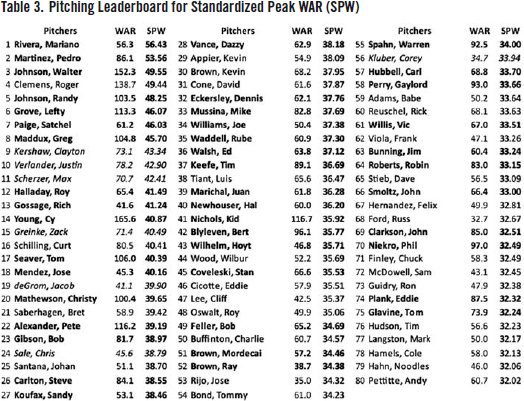

Values of total pitching WAR and SPW for the 80 pitchers with SPW ≥ 32.0 are listed in Table 3 (opposite). Of the 71 pitchers who have been retired for at least five years, 44 (62%) are in the HoF as of January 2023 (indicated in boldface type). As many as six others (Clemens, Schilling, K. Brown, Cicotte, Finley, and perhaps Pettitte) have been kept out of the HoF by issues unrelated to their accomplishments on the field. (Note that SPW values are not adjusted for alleged PED use.) Seven of the listed pitchers (shown in italics) are still active.

Two surprising features stand out from this table. First, the all-time SPW leader is reliever Mariano Rivera, who averaged more than 11 WAR per 1,000 BF over his 5103-BF career. SPW does not generally favor relievers over starters, but Rivera was an exceptional case. Rivera is one of only four relievers with SPW ≥ 32 and is the only one who pitched exclusively as a modern closer. Eckersley spent the first half of his career as a starter before becoming a one-inning closer, while Gossage and Wilhelm were multi-inning relievers, who also started 37 and 52 games, respectively, over the course of their careers. While it is easier for a reliever to post a high sWAR in a single 250-BF season than it is for a starter to do so in a 1,000-BF season, Rivera (who totaled only 5,103 BF in his 19-year career) had to produce at an elite level without a single bad season to achieve his 56.4 SPW. No other one-inning reliever has even come close to doing this.

Second, and just as strikingly, 12 of the top 16 SPW totals were posted by pitchers who were active in the twenty-first century, including four who were still active in 2022. In that respect, the SPW leaderboard stands in stark contrast to the career leaderboard for pitching WAR, in which only three of the top 16 pitchers (Clemens, R. Johnson, and Maddux) pitched into the twenty-first century and seven (Young, W. Johnson, Nichols, Alexander, Mathewson, Keefe, and Plank) pitched before 1920. This contrast largely reflects the elimination by SPW of the opportunity advantage enjoyed by old-time pitchers. However, the modern practice of protecting starters from pitching past the 6th or 7th inning may also tilt SPW in their favor.

Of the 80 pitchers listed in Table 3, 31 (39%) had <60 career pitching WAR. They fall into the following categories:

- Three Negro Leaguers: Mendez, Williams, and R. Brown. They were great pitchers, whose career totals—including WAR—underestimate their true body of work, much of which is lost to history.

- Three active pitchers: deGrom, Sale, and Kluber. Most players (except for late bloomers) come close to attaining their final SPW by their early 30s.

- Three relievers—Rivera, Gossage, and Wilhelm. It is virtually impossible for any pure reliever— even Rivera—to face enough batters to accrue 60 WAR.

- The remaining 22 belong to the group I call “sprinters,” who pitched brilliantly over 5,000 BF but were prevented by injury or inconsistency from amassing 60 career WAR. Saberhagen, Koufax, and Santana (with six Cy Young awards and an MVP among them) are illustrative examples. This group of 22 pitchers has not been favored by HoF voters; Koufax and Mordecai Brown are the only Hall of Famers among them.

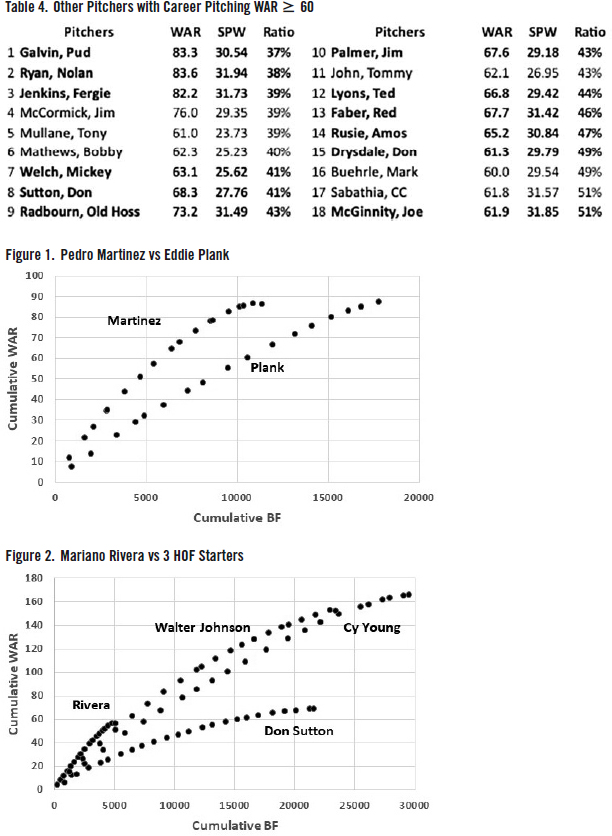

On the other side of that coin, we find 18 pitchers with SPW < 32 who sustained their value long enough to compile at least 60 WAR. They are listed in ascending order of the ratio of SPW/WAR (expressed as a percent) in Table 4. Two-thirds (12) of these pitchers are in the HoF, and Sabathia will be a strong HoF candidate when he becomes eligible in 2025. While the pitchers at the bottom of this list either barely made the 60-WAR cutoff or barely missed the 32 SPW cutoff, the top 12 pitchers could aptly be considered “marathoners.”

The contrast between the two prototypes-sprinters and marathoners—is illustrated in Figures 1 and 2, which graphically represent the season-by-season accrual of WAR, with seasons ordered by descending WAR per 1000 BF as in Table 1. Figure 1 shows the cumulative WAR accrual trajectories of two Hall of Famers who posted similar career pitching WAR almost 100 years apart, Pedro Martinez (86.1 WAR in 1992-2009) and Eddie Plank (87.5 WAR in 1901-17). Although both men exceeded the 60 WAR threshold, they followed very different tracks to get there. Martinez posted a 53.6 SPW—the best of any starting pitcher—topped by 21.5 WAR in 1,652 BF (265 composite ERA + ) in 1999-2000. Eddie Plank mustered only a 32.3 SPW with 16.4 WAR in 2,383 BF in his two best seasons (1904 and 1908). Yet, while Martinez burned out in his early 30s, Plank pitched effectively to age 41 and eventually accumulated more WAR than Martinez. Both were legitimate Hall of Famers, but Pedro is the one on the short list for the best of all time.

Figure 2, which compares the career WAR accrual trajectories of Mariano Rivera and three HoF starters— career pitching WAR leaders Cy Young and Walter Johnson and classic “marathoner” Don Sutton, illustrates the remarkable fact that Mariano Rivera managed to amass more WAR than anyone else in history in any combination of seasons totaling 5,000 BF. Of course, this does not imply that Rivera had a better overall career than Young or Johnson, who went on to face an additional 24,565 and 18,405 batters, respectively, and amass an additional 124.7 and 102.6 pitching WAR beyond their SPW. Rivera faced only 103 batters beyond 5,000 BF and accrued no additional WAR beyond his SPW. We can never know what Rivera might have done as a starting pitcher with an extra 15,000 BF to work with—not as well as Johnson or Young perhaps, but almost certainly better than “super-compiler” Don Sutton, who faced 16,528 more batters than Rivera with only 12 more WAR to show for it.

Rivera also clearly outshone “sprinter” Sandy Koufax (Table 1), who faced almost twice as many batters (9497) in his career while amassing 3.2 fewer pitching WAR than Rivera. Also, on Rivera’s side of the ledger are his stellar 0.70 ERA and 0.759 WHIP in 527 BF in postseason competition (which do not factor into WAR calculations), which were even better than his in-season 2.209 ERA and 1.0003 WHIP, which in turn rank 13th and 4th, respectively, on the all-time pitching leaderboards. Furthermore, Rivera compiled his stats in the so-called “Steroid Era,” while Young and Johnson each pitched for at least 11 years in the pitcher-friendly Deadball Era.

Finally, there are 15 HoF pitchers with total WAR < 50 and SPW < 30, well beyond striking distance of the 60 WAR and 32 SPW thresholds. They include:

- Three Negro Leaguers: Andy Cooper, Leon Day, Hilton Smith. They each have < 3000 BF on record.

- Four modern relief pitchers: Rollie Fingers (6942 BF), Trevor Hoffman (4388 BF), Lee Smith (5388 BF), Bruce Sutter (4251 BF). Not being Mariano Rivera, none could accrue more than 28 WAR in so few BF.

- Eight others: Charles Bender, Jack Chesbro, Burleigh Grimes, Jesse Haines, Catfish Hunter, Jim Kaat, Rube Marquard, Jack Morris. They simply did not have either the total or peak WAR to make the grade, despite more than ample BF totals.

RESULTS: POSITION PLAYERS (NON-PITCHERS)

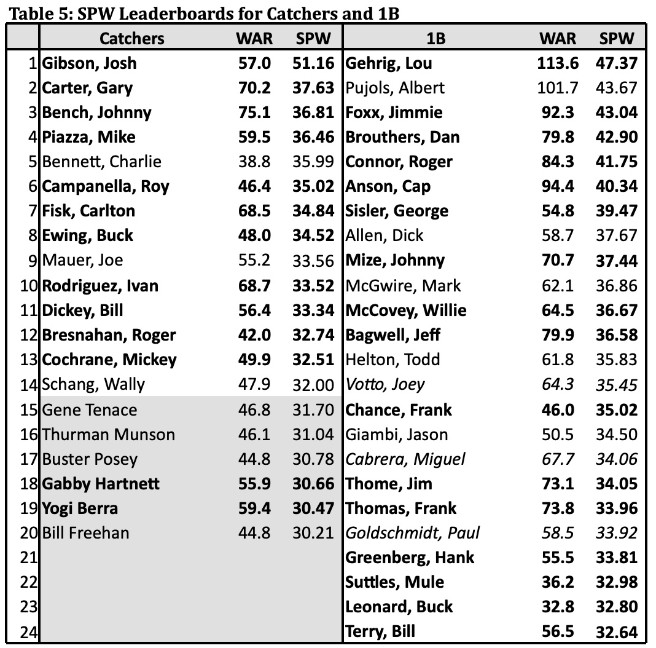

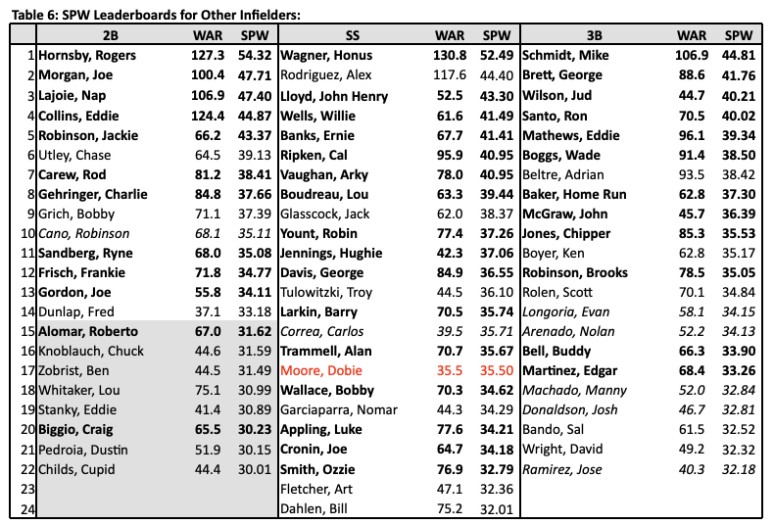

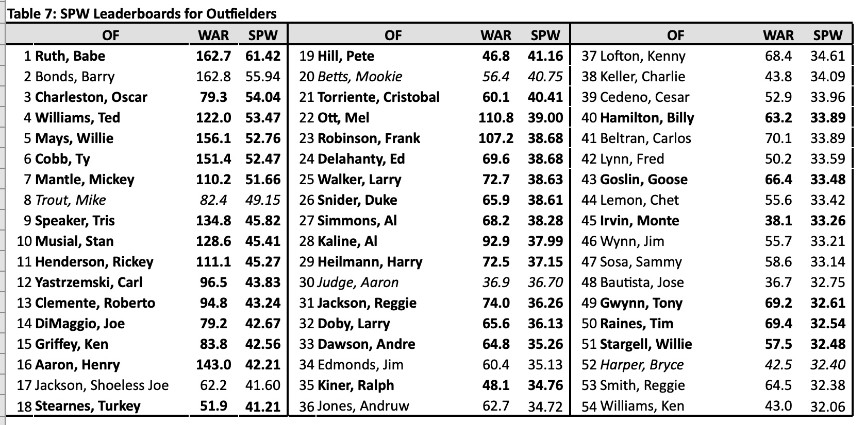

The SPW results for non-pitchers are less surprising than those for pitchers, since their WAR values are generally not distorted by huge opportunity disparities across different eras. Still, the SPW leaderboards for non-pitchers with SPW ≥ 32, which are broken down by position in Tables 5-7, give prominence to several nineteenth century players whose stats were diminished by the shorter schedules they played, catchers (who generally receive fewer PA per season than other players), players like Williams and DiMaggio, who missed several prime seasons in wartime military service, and—most significantly— pre-1947 players of color, who were confined to the Negro Leagues. As in Table 3, Hall of Famers as of January 2023 are shown in boldface type, and active players are in italics.

Because there were fewer C and 2B with SPW ≥ 32 than other IF and OF, I have extended the leaderboards for those positions to SPW ≥ 30; the extra players are shaded gray.

Of the 152 non-pitchers with SPW ≥ 32 (unshaded portions of Tables 5-7), 131 players have been retired for at least five years; 100 (76%) of them are in the HoF as of December 2022. Six others (Bonds, A. Rodriguez, J. Jackson, McGwire, Giambi, and Sosa) have been kept out of the HoF by allegations unrelated to their accomplishments on the field. The list of Hall of Famers includes 11 players who were elected as Negro Leaguers, including two—Oscar Charleston and Josh Gibson—whose SPW values place them among the top 10 peak hitters in MLB history.

The 52 (34%) of these players with <60 career WAR fall into the following categories:

- Nine Negro Leaguers: Gibson, Lloyd, Stearnes, Hill, Wilson, Moore, Irvin, Suttles, and Leonard. These were great players, whose career totals—including WAR—underestimate their true body of work, much of which is lost to history. But we have at least 3,250 recorded PA for each of them—enough to earn them a place on the SPW leaderboard. All but Moore are in the HoF.

- Ten active players: Betts, Judge, Correa, Longoria, Arenado, Goldschmidt, Machado, Donaldson, Harper, J. Ramirez. Most will likely finish with > 60 WAR.

- Ten catchers: Gibson (who also appears in the first list), Piazza, Bennett, Campanella, Ewing, Mauer, Dickey, Bresnahan, Cochrane, and Schang. Indeed, only four catchers (Bench, Carter, Rodriguez, and Fisk) have ≥ 60 career WAR, since most need frequent rest and many break down in their early 30s. All except Mauer (not yet eligible), Bennett, and Schang are in the HoF.

- The remaining 24 are the “sprinters,” who played brilliantly over 3,250 PA but were prevented by injury or inconsistency from amassing 60 career WAR. Prominent examples are Gordon, Greenberg, and Keller, whose careers were curtailed by wartime military service, and Kiner, Sisler, Tulowitzki, and Wright, who were derailed by injury in their early 30s. This group of 24 hitters has fared better than their pitching counterparts with HoF voters; nine of the 21 eligible players (41%) are in the HoF.

The SPW tables do show some mildly surprising results. For example, among outfielders Mantle outranks Aaron, Ted Williams outranks Mays, and among infielders Banks outranks Ripken, although the second player in all three pairings has the higher career WAR. However, modern players do not dominate the SPW leaderboard for hitters as they do for pitchers; the lofty historical rank of active mid-career players Trout and Betts is noteworthy but hardly surprising.

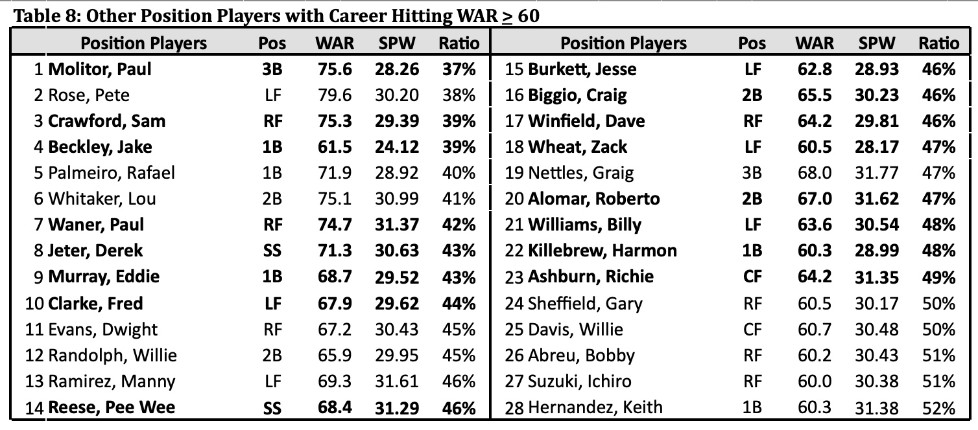

There are 28 non-pitchers with career WAR>60 whose SPW falls below 32 (Table 8).

(Click images to enlarge)

The 10 players at the bottom of this list either barely made the 60 WAR cutoff or barely missed the 32 SPW cutoff. But the top 18, including such luminaries as Pete Rose and Derek Jeter, can be aptly described as marathoners. Sixteen of the 28 players listed (57%) are Hall of Famers, but only Rose, Killebrew, and Suzuki ever won an MVP award. Ichiro will likely be elected when he becomes eligible in 2024, and Rose would be in the HoF already but for his gambling. The HoF candidacies of Ramirez, Palmeiro, and perhaps Sheffield have lost traction due to their PED-related histories. Ramirez, Sheffield, and Abreu remain on the BBWAA HoF ballot; Whitaker and Dwight Evans have received significant recent support from the Veterans Committee.

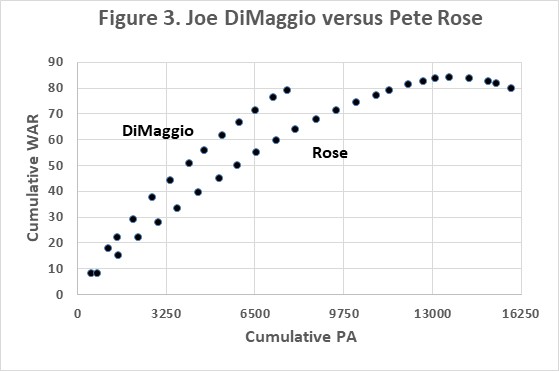

Figure 3 (analogous to Figure 1) compares the career WAR accrual trajectories of two hitters with similar career WAR totals—Joe DiMaggio with 79.1 WAR over 7672 PA in a 13-year career shortened by injuries and three years of wartime military service and Pete Rose, who amassed 79.6 WAR in more than twice as many (15,890) PA spread across 24 seasons, the last seven of which were at or below replacement level. Both had legitimate HOF credentials (setting aside Rose’s disqualification), but DiMaggio was far and away the more impactful player in his prime.

Finally, there are 37 HoF non-pitchers with total WAR < 50 and SPW < 30—well beyond striking distance of the 60 WAR and 32 SPW thresholds. They include:

- Five catchers: Ferrell, Lombardi, Mackey, Schalk, Santop. (Mackey and Santop also appear on the Negro League list.) WAR consistently undervalues catchers.

- Six Negro Leaguers: Bell (6747 PA). Brown (2324 PA), Dandridge (2547 PA), Johnson (4345 PA), Mackey (4340 PA) and Santop (1977 PA). The statistical records are skimpy for all except Cool Papa Bell. I have not counted Buck O’Neil (elected largely for his non-playing contributions), nor Bud Fowler or Frank Grant (almost no data).

- Twenty-eight others: Baines, Bottomley, Brock, Combs, Cuyler, Duffy, Evers, Fox, Hafey, Hodges, Kell, Kelly, Lazzeri, Lindstrom, Manush, Maranville, Mazeroski, McCarthy, Oliva, J. Rice, Rizzuto, Roush, Schoendienst, Thompson, Traynor, L. Waner, Ward, Youngs. They simply did not have either the total or peak WAR to make the grade, despite more than ample PA totals.

IMPACT OF PED

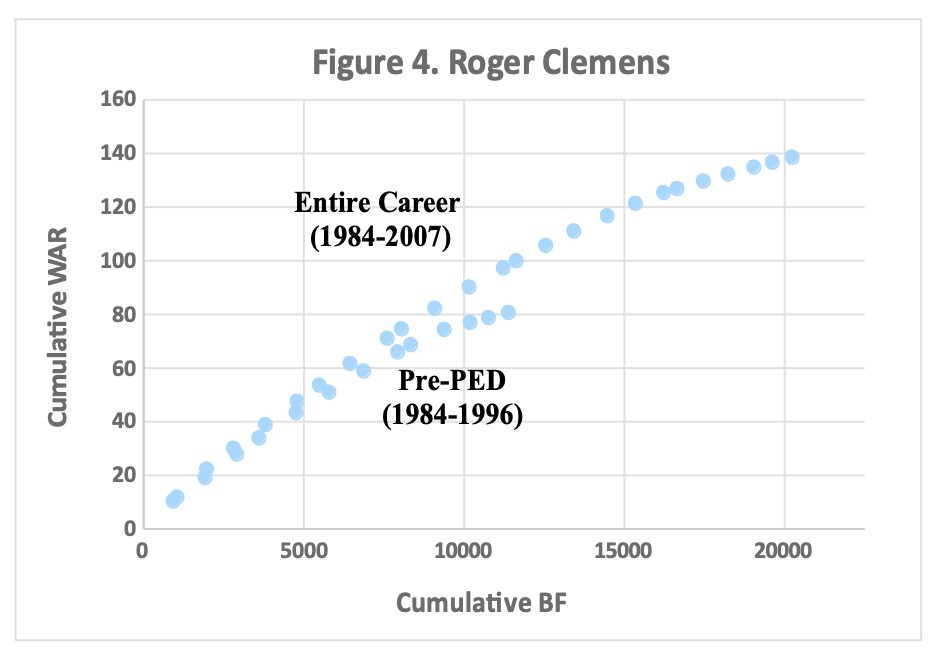

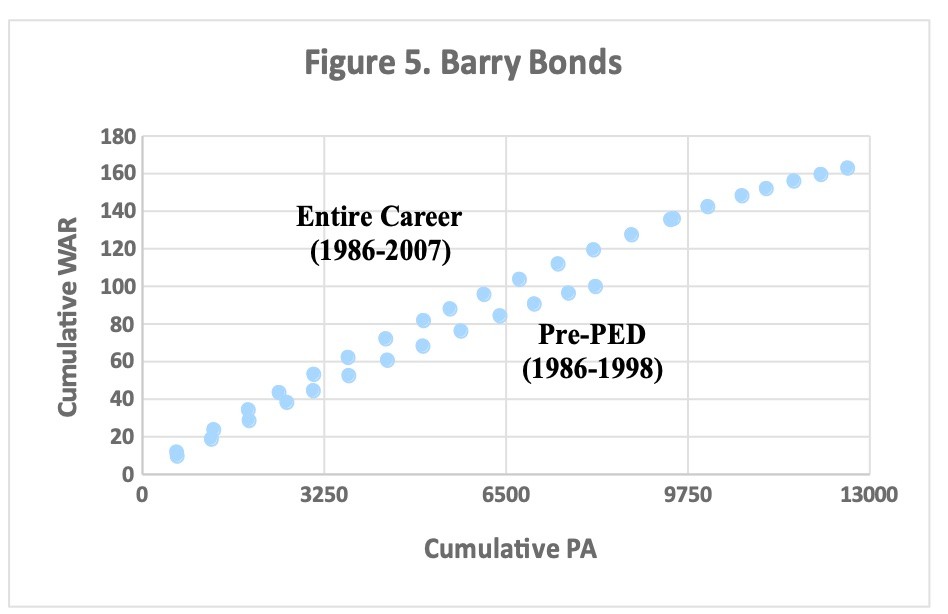

I have noted above that the SPW ≥ 32 leaderboards (Tables 3 and 5-7) contain several players who have been implicated as PED users. We do not have reliable time lines of PED usage for most of these players, but the chronologies for Bonds (who allegedly began using PED in 1999) and Clemens (who allegedly began using in either 1997 or 1998) are well documented.12,13 In Figures 4-5, the overall career WAR accrual trajectories for Clemens and Bonds are compared to the truncated trajectories that include only their pre-PED seasons.

Clemens’s SPW fell from fourth (49.4) to eighth (45.1) among all pitchers when his 1997-2007 seasons are excluded. Bonds’s SPW fell from second (55.8) to 14th (46.9) among all non-pitchers after his 1999-2007 seasons, which include his four best seasons (2001-4), are excluded. The “PED years” clearly inflated Bonds’s SPW more than that of Clemens. However, even with out his alleged steroid seasons, Bonds’s SPW still outstrips such luminaries as Eddie Collins, Lou Gehrig, Tris Speaker, Rickey Henderson, Stan Musial, Mike Schmidt, Henry Aaron, Mel Ott, and nearly everyone else who ever played MLB. Like Clemens, Bonds did not need steroids to place him among the greatest players of all time.

DISCUSSION

Peak as well as total value has always been considered in the HoF selection process. As Bill James has phrased it, we think of “black ink”—triple crowns, ERA titles, etc.—and major awards. when we anoint our Hall of Famers.14 We esteem the accomplishments of players like Sandy Koufax, who spent a half-decade among the elite players in baseball, even though their career totals may not be especially impressive. However, while WAR has given us a comprehensive (If Imperfect) metric for career value, we have lacked a fair and unbiased quantitative measure of peak value. Jaffe’s WAR7, which he uses to calculate JAWS, is a poor indicator of peak value because the WAR values for a player’s best seven seasons are often based on widely differing numbers of opportunities to produce value, i.e., PA for hitters or BF for pitchers.

Obviously, WAR systematically undervalues players whose careers were confined to the Negro Leagues. The HoF has been addressing this issue systematically by delegating it to a special committee with appropriate resources and historical expertise. SPW validates most of their selections where sufficient data exist.

The biggest issue for other hitters is the systematic undervaluation of catchers by career WAR (which is only partially addressed by SPW). However, HoF voters have done a pretty good job of using subjective criteria to honor catchers with < 60 WAR who had high peak value. The only glaring omission is nineteenth century catcher Charlie Bennett whose late-career effectiveness was hampered by injuries and who ultimately lost his leg in a train accident. HoF voters have also done a reasonably good job of honoring other worthy high-peak hitters like Greenberg, Sisler, and Kiner, who fell well short of 60 WAR.

The absence of a standardized measure of peak value has been far more problematic for pitchers due to the huge historical disparity in the distribution of BF. Jaffe’s unstandardized WAR7 grossly overestimates the peak value of nineteenth century pitchers (who often pitched 400-650 innings per season) and underestimates the peak value of relief pitchers (who now pitch about 60 innings per season) and modern starters (who now pitch 180-200 innings per season). While HoF voters have recognized the inadequacy of WAR-based metrics for relief pitchers, they have over looked the elite peak performance rates of pitchers like Johan Santana, Bret Saberhagen, Kevin Appier, and David Cone, who did not compile impressive career totals. Jaffe himself has recently introduced a fudge factor to modify the calculation of JAWS to correct for these inequities (s-JAWS and r-JAWS).15 But if we really want a fair and unbiased estimate of peak value, we need to replace the seven-season construct by one based on a standard yardstick of a fixed number of PA or BF. That is what Standardized Peak WAR does.

The specific choices of 3,250 PA and 5,000 BF to be the yardsticks for computing SPW, intended to represent five full-time seasons for the typical mid-twentieth century player, are somewhat arbitrary. They are meant to be a large enough body of work to exclude the “flashes in the pan” who have one or two flukish seasons, but short enough to include great players who received limited opportunities to accrue WAR. If I had chosen 4,550 PA and 7,000 BF to align more closely with Jaffe’s WAR7, Negro Leaguers and relief pitchers would not have fared as well.

When we compare the leaderboards for SPW with those for WAR, we see some striking differences. First, we see the Negro League hitting and pitching stars assume their rightful place among the all-time greats. Josh Gibson’s 51.2 SPW leads all catchers by far, despite his modest 57.0 career WAR. Oscar Charleston’s 54.0 SPW ranks behind only Ruth, Hornsby, and Bonds among all hitters. On the pitching side, Satchel Paige’s 46.0 SPW ranks seventh, behind only Rivera, Martinez, W. Johnson, Clemens, R. Johnson, and Maddux.

Second, we see modern starting pitchers—even active ones like Kershaw, Verlander, Scherzer, and Greinke—move to the fore. While their diminished work loads hold back their values of WAR, WAR7, and JAWS, their peak value (as measured by SPW) is probably enhanced by being better rested than their workhorse predecessors. Still, the best of the old-timers—W. Johnson, Young, Grove, Mathewson, Alexander, etc.—hold their own on the SPW leaderboard.

Third, we see 14 catchers with SPW ≥ 32, versus only four with WAR ≥ 60 and five with JAWS ≥ 50. However, I would argue that catchers are still under valued by SPW—just not as badly. I don’t think WAR captures the full defensive value of catchers, who are the only defenders except pitchers who have a hand in every pitch. Yadier Molina is widely predicted to be a first-ballot Hall of Famer, but his SPW is only 26.4.

Fourth, a relief pitcher, Mariano Rivera, tops the SPW pitching leaderboard. However, even SPW can do little for most modern one-inning relievers. In terms of WAR per 1,000 BF, Billy Wagner (38.6) is the most impressive of any post-1990 closer except Rivera. But this is based on only 27.8 WAR in only 3,600 BF (the equivalent of about 1.3 Hoss Radbourn seasons). Wagner has received significant HoF support, but I am not convinced that his total value is enough to warrant his selection for the HoF.

SPW is not meant to be a stand-alone stat to deter mine who belongs in the HoF. Quantity as well as quality still matters. One could follow in Jaffe’s footsteps and combine WAR and SPW to form a comprehensive JAWS-like statistic. Unfortunately, the contribution of SPW, which ranges only up to 61.4 (for Babe Ruth), would be swamped in a simple average by the contribution of WAR (which exceeds 160 for Bonds, Ruth, and Young). I prefer my own invention, the Gordon Career Value Index (CVI), which begins with WAR and awards extra credit for all seasons in which WAR> 5.0 per 650 PA or 1,000 BF.16 An added advantage of CVI is that, unlike SPW, it incorporates both hitting and pitching value in a single metric and thus gives full credit to two-way players and good-hitting pitchers.

Although WAR is the best comprehensive performance metric we have, it has limitations. The methodology for calculating WAR is opaque and differs across plat forms. Also, since Baseball-Reference.com periodically tweaks their WAR calculations, many of the SPW values in this article may have changed by the time you read it. The positional adjustments and defensive component of WAR for non-pitchers are somewhat arbitrary and do not necessarily reflect the state of the art. I also believe that WAR undervalues the defensive value of catchers and overly penalizes designated hitters for their absence of defensive value.

The key point of this analysis is that the evaluation of any player’s qualifications for the HoF should include the height of their performance peak—not just career totals. JAWS does not do this well because its measure of peak value reflects widely varying numbers of BF or PA. The SPW methodology introduced here standardizes peak WAR to 5,000 BF for pitchers and 3,250 PA for non-pitchers. Thus, one can fairly compare the SPW of players of all eras—those who played 60-game or 162-game schedules, those who played 12 or 24 years, those who lost substantial time to injuries or military service, those who spent much or all of their careers in the Negro Leagues, and pitchers who started 90% or 15% of their team’s games or even those who pitched only in relief.

DAVID J. GORDON, MD, PhD is a retired cardiovascular clinical trialist, formerly with the National Institutes of Health. Since his retirement he has written two books, Baseball Generations and The American Cardiovascular Pandemic: A 100 year History, and has contributed several articles to the Baseball Research Journal.

Sources

1. Baseball-Reference.com WAR Explained, https://www.baseball-reference.com/about/war_explained.shtml.

2. Keith Law, Smart Baseball, Harper Collins, 2017, 183-203.

3. Jay Jaffe, Cooperstown Casebook, St. Martin’s Press, 2017, 22-27.

4. Baseball-Reference.com, Jaffe WAR Score System (JAWS), https://www.baseball-reference.com/about/jaws.shtml.

5. David J. Gordon, Baseball Generations, Summer Game Books, 17-38.

6. Baseball-Reference.com, https://www.baseball-reference.com.

7. Baseball-Reference.com, Starting Pitcher JAWS Leaders, https://www.baseball-reference.com/leaders/jaws_P.shtml.

8. Baseball-Reference.com, Year-by-Year Top-Tens Leaders & Records for Batters Faced, https://www.baseball-reference.com/leaders/batters_faced_top_ten.shtml.

9. Baseball-Reference.com, Year-by-Year Top-Tens.

10. Seamheads Negro League Database, Wins Above Replacement, 1886-1948, https://www.seamheads.com/NegroLgs/history.php?tab=metrics_at&first=1886&last=1948&lgID=All&lgType=All&bats=All&pos=All&H0F=All&results=100&sort=Tot_a.

11. FanGraphs, https://www.fangraphs.com.

12. Mark Fainaru-Wada and Lance Williams, Game of Shadows, Gotham Books, 2006.

13. Frederick C. Bush, SABR Biography of Roger Clemens, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/b5a2be2f.

14. Bill James, Whatever Happened to the Hall of Fame?: Baseball, Cooperstown, and the Politics of Glory, Fireside Books, 1994, 1995.

15. Baseball-Reference.com, Jaffe WAR Score System (JAWS).

16. David J. Gordon, Using Career Value Index (CVI) to Evaluate Hall of Fame Credentials of Negro League Players, Baseball Research Journal, Fall 2022, 51:112-21.B