Community of Inquiry: A Blueprint for Bringing Baseball to African American Youth

This article was written by David C. Ogden

This article was published in Fall 2021 Baseball Research Journal

From youth “select” baseball to the major leagues, the percentage of players who are African American has reached a historic low. As low as the percentage on 2020 MLB teams’ 30-man rosters had ebbed (7.5 percent1), it is even lower among college players and youth players.2 Scholars and pundits have offered reasons for, and solutions to, the decades-long disappearance of African Americans from the nation’s ball fields. Their science-based solutions to address this demise rely on concepts in the social sciences and offer insights into African Americans’ lack of involvement in baseball.3 While those insights provide valuable theoretical guidance, they do not focus on the essence of the issue: Youngsters must be taught baseball to appreciate baseball. The literature lacks a pedagogical — or teaching-driven — approach in analyzing the paucity of African Americans in baseball.

Some organizations have tied baseball to other learning programs for inner city youth. Elementary Baseball in Washington, DC, for example, offered baseball instruction as a reward for participating in a literacy program mentored by judicial officials.4 The approach proposed in this article extends educational principles into the teaching of baseball itself. This approach considers youth baseball as it is: a learning experience. It also provides ideas to increase interest in baseball by African American youth to the point that they graduate to higher levels of competition and subsequently to college and the professional ranks.

A fulfilling learning experience is needed to build the relationship between African American communities and baseball. An overarching educational paradigm incorporating interactive elements, called the Community of Inquiry, or CoI, would provide that experience. CoI emerged with the growth of online classes and technology in higher education,5 and describes a framework for maximizing an individual’s virtual learning environment, but has not been applied to interest or involvement in sports, much less baseball. When used as a lens to look at African Americans and baseball, CoI draws together theoretical perspectives from leisure studies, sport sociology, and cultural studies. Just as importantly, CoI offers a holistic approach by binding those perspectives and showing how they interact.

Individually, those perspectives have been discussed — some more than others — in the sports sociology and baseball research literature. The intent of this article is to add to the scholarship by examining the low number of African Americans in competitive baseball, previous research on the issue, and the coalescence under the CoI framework of theoretical perspectives from that research, all in an effort to understand factors affecting the likelihood of African American youth becoming engaged in baseball.

LITERATURE REVIEW

The concept, Community of Inquiry, as described by D. Randy Garrison, Terry Anderson, and Walter Archer, aims to provide a model to engage students through computer conferencing and to identify the elements necessary to optimize learning. The model reflects the basic tenets of learning as laid out more than 60 years ago by pedagogical scholar and writer, John Dewey. Dewey maintained that “the educational process has two sides — one psychological and one sociological” and “neither can be subordinated to the other.”6 Elaborating on Dewey’s concepts in developing the CoI model, Garrison and colleagues describe the environment most conducive to a positive learning experience and the creation of a learning cohort.7 Collectively, sports sociologists have described those same elements, but in different terms. The three conceptual “pillars” of the CoI are teaching presence, social presence, and cognitive presence. The pillars and concepts from the sports and leisure sciences and cultural studies covered by each pillar can be synthesized as follows.

Teaching presence. As perceived by Garrison and his colleagues, “direct instruction” is at the core of developing teaching presence. “Teacher immediacy” facilitates communication between teacher and student.8 The teacher helps to shape the learning environment by setting “explicit and implicit structural parameters and organizational guidelines” and by enhancing “understanding through various means of assessment and feedback.”9 The teacher bears responsibility for “providing immediate and diagnostic feedback to student responses.”10 Baseball coaches do the same when they teach the game. Beyond skills instruction, though, coaches contribute to the social presence by serving as authority figures. They, like teachers, organize and construct the learning experience for their players and serve as accessible instructors.

The sports sociology literature and the mainstream media tend to focus on the importance of a coaching “presence,” with the mainstream media quicker to point out the causes of the absence of that presence for baseball in African American communities. “The demise of the two-parent household and the passionate neighborhood volunteer coach have cut the connection between baseball and young blacks,” Tom Verducci wrote in a 2003 article in Sports Illustrated.11 Verducci’s concerns have been echoed for years by journalists such as David Canton of U.S. News, who observed that “deindustrialization, suburbanization and mass incarceration….[have] had a disproportionate impact on black men and their community and are the major reason why the percentage of black baseball players has declined since 1981.”12

That lack of role models stymies one of the CoI’s most fundamental elements to teaching presence: “building understanding.” Like the youth baseball coach and his players, “the teacher draws in less active participants, acknowledges individual contributions, reinforces appropriate contributions,…and generally facilitates an educational transaction.”13 Those transactions can’t take place, according to the CoI paradigm, without a teacher who provides meaningful, timely, and personal instruction. Like the role of the teacher in a community of inquiry in building a “group consciousness,”14 the coach assumes the responsibility of building cohesiveness among the learners or, if you will, a team mentality.

Social presence. The concept of social presence refers to fostering a feeling of community and interdependence among fellow learners. Garrison and colleagues say social presence depends on three elements: “emotional expression, open communication, and group cohesion.”15 Social presence can contribute greatly to learning when the participants “find the interaction in the group enjoyable and personally fulfilling.”16 Garrison said that “a sense of belonging” indicates that a participant feels comfortable with fellow learners. “[T]he more individuals know about each other the more likely they are to establish trust, seek support, and thus find satisfaction.”17 African American youth desire that same “sense of belonging” when playing a sport. Sports sociologists and educators agree that identifying with a group enhances the learning experience. Affiliation with peers and other “interpersonal” connections drive a youth’s interest and desire to play a particular sport.

For a sport to attract a youngster, it must provide an opportunity to bond with peers.18 That desire for affiliation with a social group rings true especially for African Americans. Steven F. Philipp — who has published widely about how “welcome” or “unwelcome” African Americans feel within certain sports — and Sherie Brezina found that African American youth, more often than “EuroAmericans,” identify “social interaction” as one of the most important reasons for participating in a sport.19

But parents, as another interpersonal connection, lay the groundwork for their children’s interest in particular activities, and African American parents are most likely to steer their children to basketball over all other team sports.20 When it comes to baseball, scholars Shaun Anderson and Matthew Martin claim that lack of parental involvement can kill a child’s interest and chances of playing.21 According to another study, parents from minority groups and lower socioeconomic levels are less likely than more affluent parents to support their children’s sports activities.22 Together, peers and parents (and other family members) create the social milieu and background that shape a student or young baseball player’s learning environment. The player is ensconced in the social presence created by those groups.

Cognitive presence. This concept entails the “reciprocal relationship between the personal and shared worlds.” Critical thinking shapes cognitive presence through “the integration of deliberation and action” and “reflects the dynamic relationship between personal meaning and shared understanding (i.e., knowledge).”23 But the learning process takes place “within the broader social-emotional environment,” as Garrison notes.24 That is, students bring their own backgrounds and intrapersonal traits to learning experiences and learn from each other as they acquire new knowledge. The same can be said for youngsters who are exposed to a sport and the skills which must be learned to play it. Those intrapersonal traits, as defined by Stodoloska and colleagues, encompass “virtually any personal attribute that influences the way an individual views the world and the opportunities it offers.”25

To whatever degree interpersonal relationships and social and cultural environment shape those traits, a OGDEN: Community of Inquiry youth looks for resonance between his self-image and the sport he decides to play. Researchers Brandon Brown and Gregg Bennett say this rings true especially for African Americans. Brown and Bennett contend that “African Americans [more so than other racial groups] must perceive a sense of congruence between their racial identity and baseball before choosing to consume the sport. This is supported by literature, as research suggests individuals will likely consume a product given the product possesses features that are representative of one’s sense of self-identification”.26

Just as a student must acquire and synthesize knowledge and data to overcome “a state of dissonance or feeling of unease” when confronted with an intellectual or cognitive challenge (according to Garrison’s description of “critical inquiry”),27 a youngster must learn and then repeatedly practice the basic skills necessary to surmount the challenges of playing baseball. To what extent a youngster can find resonance between self-image and the sport will determine how much the youngster devotes to the sport, just as the student’s cognitive presence determines the student’s degree of and success in “critical inquiry”.28

THE LOW NUMBER OF AFRICAN AMERICANS IN BASEBALL

In the 2020 Complete Racial and Gender Report Card, Richard Lapchick shows the disparity between the percentage of players who are Black in Major League Baseball (7.5 percent in 2020) and those percentages in the National Basketball Association and National Football League (74 and 57 percent, respectively). Numerous reasons for the disparity have been offered, such as authority figures encouraging African American youth to play sports other than baseball, more peer involvement in basketball and football, higher visibility of role models in those sports, and socioeconomic restraints.

Regardless of the reasons, the 2020 MLB percentage marked the lowest since the first Racial Report Card in 1991.29 That also marked a 60-year low (according to another study) when African Americans constituted 7.4 percent of players on 1958 major league teams. During the next 15 years, that percentage steadily climbed and remained above 17.4 percent between 1973 and 1987. The percentage peaked at 18.7 percent in 1981.30 Since 2010, it has remained under 9 percent.31

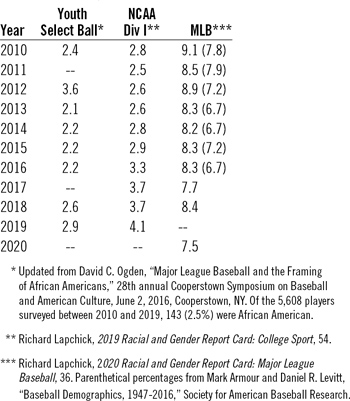

The percentage of African Americans on NCAA Division I baseball rosters also remains mired in the single digits. Since 2010 that percentage has ranged between 2.5 and 4.1, the latter in 2019.32 The percentage of African Americans at the highest levels of competitive youth baseball dips even lower. An 18-year study of youth select — or “travel team” — baseball shows that during the past decade (2010–19), the percentage of African Americans hovered between 2.1 and 3.6 percent (See Table 1). Overall, during the 18 years of primary research on youth select teams, less than 3 percent of the almost 10,000 players were African American.33

Table 1. Percentage of Players Who Are African American, 2010–20

The data on teams were collected each summer from 2000 to 2019 (excluding 2011 and 2017) at regional and national youth select baseball tournaments in the Midwest. In all, 843 teams from 35 states and consisting of 9,783 players, ages 10 to 18, were surveyed. These tournaments included the Slumpbuster Tournament Series, considered the nation’s largest select baseball tournament and held concurrently with the NCAA College Baseball World Series each year in Omaha and Lincoln, Nebraska, and Council Bluffs, Iowa.34 Between 40 and 75 teams were surveyed each summer.

As with the research by Armour and Levitt, “skin color” was the “determining factor” in identifying African American players.35 In this case, facial appearance also served as a determining factor. Printed tournament programs often featured names of players and team photos, as did banners some teams hung outside their dugouts. Those visual materials helped to identify Black players, possibly with a Hispanic background. When in doubt about the racial composition of the team, the researcher consulted a coach or parent for verification.

The low percentage of African American youths in select baseball presents a challenge for those intent on increasing the number of African Americans at higher levels of baseball. Select baseball differs from other forms of youth baseball such as Little League, YMCA, Catholic Youth Organization, and private youth sports organizations. Select teams usually are formed via competitive tryouts and play regionally and nationally against other elite competition.36

According to research literature and even mainstream news sources, select baseball has become the prominent pool of talent for high school and college baseball. Select baseball’s impact on major league rosters begins at the college level. A national study of almost 500 college baseball players found that 90 percent of them played in youth select baseball for an average of 6 years.37 With college players now comprising more than 75 percent of those drafted by MLB teams, extrapolation of the results from the college baseball study shows that more than two thirds of those draftees played select ball.38 Thus, youth select baseball initiated the majority of those draftees to high-level competition and served as the entry point to the talent pipeline that eventually leads to the major leagues.

Comparing the percentages of African Americans in the major leagues, college baseball, and youth select ball shows a “constriction” in the number of African Americans moving up that ladder of competition. (See Table 1) Increasing the number of African American youths in any type of competitive baseball doesn’t guarantee that the number will increase at the college and major league levels, but at the very least, it would increase the potential pool of players moving forward. Major League Baseball has invested in urban baseball initiatives like RBI (Reviving Baseball in Inner-cities) and the Breakthrough Series. A model for teaching the fundamental skills and philosophy of baseball and addressing impediments to learning them could improve the results from these programs. The CoI can serve as a core for such a model.

COI AND STRUCTURING BASEBALL OUTREACH FOR AFRICAN AMERICANS

The CoI model offers a three-pronged approach for understanding and addressing the chronically low number of African Americans in baseball. Viewing the problem as a pedagogical challenge (i.e. the simple act of teaching a child to play and/or understand baseball) can address the larger relationship between African Americans and baseball. The CoI model integrates multiple considerations for narrowing the gulf between African American youths and baseball. Each presence — teaching, social, and cognitive — draws in threads of discussion from the research literature and observations by baseball writers. More importantly, CoI provides direction for identifying (or confirming) “best practices” for teaching baseball to youngsters, especially those with little or no exposure to the game.

Teaching presence. The role of coaches looms large, according to some research. Young African Americans in an RBI program told Stodoloska and colleagues that they grew to respect and admire their coaches.39 African American youths participating in the RBI program said coaches shaped their baseball experience and facilitated learning baseball skills. The researchers concluded that “the support and encouragement from coaches and program staff were important factors” in keeping players engaged in RBI.40

In Verducci’s 2003 SI article, he wrote that even more important than formal coaches were informal coaches, or “pied pipers.”41 Verducci was quoting the late John Young, a former major league player and scout and the founder of RBI who used the term “pied piper” to describe the men who voluntarily taught youngsters baseball in the South Central Los Angeles neighborhood where he grew up. Fathers usually served in that role, but as Verducci wrote, with the high number of fatherless households in the inner city, the role may go unfilled, and “Without its pied pipers, baseball, the more pedagogic game, suffers.”42

Player Bryson Graves receives encouragement from a coach during the 2021 WWBA Underclass World Championship. The Breakthrough Series, established in 2008, is a joint effort between USA Baseball and Major League Baseball aimed at developing players on and off the field through mentorship and instruction and is one of MLB’s “diversity pipeline” programs. (MARY HOLT/MLB PHOTOS)

To be effective, pied pipers must provide a consistent presence, not just for a few weeks in the summer. And for a community of inquiry to be effective, it must have “high levels of ‘teacher immediacy.’”43 For young baseball “students,” that immediacy comes in the form of regular contact with a baseball mentor. Whoever serves as that mentor must have credibility (or “street cred”) and youths must be able to identify him or her as part of their neighborhood or culture. Youths must consider that mentor as someone who understands the problems and pressures of living in impoverished neighborhoods or with those who are at the lower rungs of the socio-economic ladder. To be effective, that mentor should be a part of that local community or someone who has lived in that community.44

A few youth baseball mentoring programs have shown success by selecting coaches who spend considerable time in the community. Home Run Baseball Camps have followed that practice for years. Home Run Baseball founder John McCarthy described one of his young female coaches in Washington, DC: “She grew up alongside these kids. So when she goes into predominantly black neighborhoods, she takes no s— from anybody. She knows exactly what’s going on.” That coach, like other Home Run Baseball coaches, will spend years following the development of the players who stay in the program. Such “immediacy” to instruction through frequent contact and familiarity between coach and player facilitate the player’s development and growth, just as “teacher immediacy” facilitates a student’s learning and sense of belonging in the CoI. McCarthy said that players who stick with the program “catch on fire for baseball. They’re into it. They love it. They’re competitive.”45

Former New York Mets and Chicago White Sox manager Jerry Manuel has carried the concept of teacher immediacy a step further. He formed a nonprofit organization which, among other activities, works with charter school programs in Sacramento to teach baseball to Black children by letting them learn and play the sport as part of their regular curriculum. Manuel believes such measures can bring baseball back to the forefront of African American culture. “One of the pillars of our community was baseball,” he said. “That baseball pillar has crumbled somewhat, but I still think that there’s gonna be a surfing back, if you will, to where baseball comes back to what it was.”46

Social presence. As with CoI, social and cultural ties have much to do with a youngster’s propensity for seeking sports participation. As noted earlier, researchers most often cite peer groups and parents as the most influential in socializing and sanctioning sport for youngsters. Sociologist Anthony Giddens noted, “The generation of feelings of trust in others, as the deepest-lying element of the basic security system, depends substantially upon predictable and caring routines established by parental figures.”47 Shaun Anderson and Matthew Martin claim that when parents aren’t involved, youngsters aren’t likely to play baseball.48 The RBI directors interviewed by Anderson and Martin said that getting parents to participate “is key” to getting African American youth on the baseball diamonds. One of the directors lamented: “Getting our participants [players] to and from games and getting our participants to and from the Urban Youth Academy hurts our growth. We need parents’ help in this situation.”49 Providing transportation, helping their children find opportunities to play, and using discretionary time and money to encourage their involvement are among the ways parents can support their children’s participation in baseball.

Peer influence also looms large in setting the social and cultural tone of a youngster’s sporting experience. Stodoloska and her co-authors said the RBI players in their study “discussed feelings of closeness, connection, comradeship, pride, and enjoyment they experienced while interacting with their teammates.”50 As discussed earlier, research has established that for a sport to attract a youngster, it must provide an opportunity to bond with peers. Based on such studies, those who try to pique African American youth interest in baseball should consider the peer groups a youngster deems important. Being aware of what a youth’s peer culture does and does not value can provide information for coaches in determining what may be most effective to teaching baseball.

In the absence of parental support, coaches can impact a youth’s baseball experience beyond sustaining a teaching presence. As Stodoloska wrote, coaches “are particularly important for children with low self-esteem who depend on their encouragement and support.”51 In establishing a social presence, as explained by Garrison, the teacher (or coach) acts as more than just a purveyor of information. That person also acts as a partner, or collaborator, with the student in directing the discovery of new knowledge (or skills) and in helping students learn from each other. As CoI originators L. Randy Garrison and colleagues explain, “Collaboration is an approach to teaching and learning that goes beyond simple interaction and declarative instructions. Collaboration must draw learners into a shared experience for the purposes of constructing and confirming meaning.”52

Based on the CoI perspective and research like that of Anderson and Martin, coaches of first-time players should consider spending as much, if not more, time with individual instruction as they do on group fielding and hitting drills. That means working with players one-on-one on the mechanics of fielding, hitting, and pitching, and relating to the players off the field, not just on the field. But coaches should also allot time for youngsters to apply their skills by playing with each other in a relaxed atmosphere, with the coach stressing adherence to that which was taught.

Cognitive Presence. Garrison notes that cognitive presence can be nurtured through a strong social presence, just as Dewey said that the psychological and sociological aspects of learning are two sides of the same coin. If the youngster can find cultural fulfillment with peers through baseball and, as Garrison might say, “personal meaning” in the “knowledge” gained from coaches,53 then the youngster may internalize baseball participation to the extent to which the sport becomes part of the youngster’s self-image. “That is, socio-emotional interaction and support are important and sometimes essential in realizing meaningful and worthwhile educational outcomes,” Garrison and his co-authors wrote.54 In such a case, repeated exposure to baseball may result in the youth incorporating the role of “baseball player” as part of his identity. This is particularly salient for African Americans, according to research by Brown and Bennett, because “minorities have a stronger sense of self-identification than other ethnic or racial groups… This is significant because a strong identity toward one’s self will encourage behaviors that affirm identity characteristics.”55 As noted earlier, the “sense of [racial] congruence” is paramount in an African American youth’s decision to play baseball.56

Incorporating a sport into one’s self-identity goes beyond just learning the skills of the sport. Sports sociologist Jan Ove Tangen argues that even the venue where the game is played can have an intrapersonal impact. The venue itself can arouse excitement and anticipation for competition and provide comfort and confidence through the familiarity of the playing space. Tangen says research has “documented how people may feel affection for sport places and experience different qualities of the facility with beneficial consequences to their identity, health and so on.”57 The playing space is where the physical demands of the sport and the social and psychological attraction, or cognitive presence, meet and where the player reveals a part of his self-identity. From the CoI perspective, this sense of self plays within a larger “social-emotional” environment.58 As several researchers have found, people feel “welcome” in some sports venues, but not in others, based on their own history (or lack of it) with the venue and the cultural significance they and friends and family place on the venue.59 The venues which a youngster finds welcoming can spur his “purposeful thinking and acting” in growing into the sport. That allows the youngster to fuse “personal meaning and shared understanding (i.e. knowledge)” which Garrison said are necessary for cognitive presence.60 Tangen says that for the youngster, the venue can elicit a fundamental question: “‘Who am I?’ Through repeated reflections such as this the identity of the individual develops.”61

Stodoloska’s research bears out Tangen’s claim that the playing space itself bolsters a youth’s cognitive presence when playing a sport. The African Americans in their study felt that the RBI program provided a safe place for them to learn the game and have fun with peers. Stodoloska concluded that “the desire to satisfy the need for safety may actually motivate some youth to increase participation in organized and supervised sport programs that provide safe havens in urban impoverished communities.”62 The researchers proposed that a youth’s desire for a safe recreational place should figure into “future theoretical models” for attracting youth to baseball.63 Making such space available and accessible should be a consideration when trying to root and grow baseball programs for inner city youth. Both public and private investments in neighborhood baseball fields are necessary to ensure that happens.

CONCLUSION

In the Community of Inquiry, teaching presence, social presence and cognitive presence intertwine. When applied to baseball instruction, teaching (coaching) presence “is essential in balancing” cognitive presence and social presence.64 In looking at inner city youth baseball programs through the lens of CoI, the coach transcends his or her traditional role and becomes a pied piper, a neighborhood ambassador of baseball, and even a parental or trusted authority figure. In this role the coach attempts to connect culturally with novice minority players and to recognize the interpersonal influences on those players.

The coach also provides an accessible but safe environment for playing baseball. Having that trusted coach or mentor, an enclosed and secure playing field, supportive peers, and a growing familiarity with baseball can shelter a youngster, at least temporarily, from the grit of the inner city. While not as straightforward as it may sound, an effective youth baseball program that provides such an environment for nurturing an interest in the game can be built around the tenets of CoI.

The low percentage of elite-level players who are African American (from youth select ball to the major leagues) persists, despite programs aimed at increasing that percentage that have been in place for years. In the 2020 Racial and Gender Report Card: Major League Baseball, Richard Lapchick said that baseball organizations should “put a direct focus on continuing to grow the game in communities which do not have access” to baseball.65 Major League Baseball formed the RBI program and other initiatives to do just that. But within the past few years, researchers contend that RBI has failed to develop long-term, meaningful relationships with many underserved communities, which “shows that MLB either does not care about developing these relationships or that MLB is not concerned about making changes within these communities.”66 While Lapchick sees signs for optimism,67 the number of African Americans playing at high levels of competition remains stagnant.

Treating baseball as an individual learning challenge and incorporating the CoI model can be a tool for nurturing the game in baseball “deserts” and can allow baseball coaches and organizers to provide more immersive experiences for their youthful novices. On a larger scale, framing baseball as an educational activity allows youth baseball organizers to take advantage of other pedagogical research on enhancing the learning environment and improving student outcomes. Such an overview opens new possibilities for addressing the chronically low number of African Americans in elite youth baseball, and subsequently at college and professional levels.

DAVE OGDEN, PhD is professor emeritus in the School of Communication at the University of Nebraska at Omaha. He has presented his research at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Conference on Baseball and American Culture, the Nine Spring Training Conference, and in the Baseball Research Journal, Journal of Leisure Research, and Journal of Black Studies. He is co-editor of three books on sports and reputation and co-authored the book, Call to the Hall.

Notes

1. Richard Lapchick, 2020 Racial and Gender Report Card: Major League Baseball, The Institute for Diversity and Ethics in Sport (Orlando: University of Central Florida, August 28, 2020): 36, https://43530132-36e9-4f52-811a-182c7a91933b.filesusr.com/ugd/7d86e5_3267492245744522893b464512c42cad.pdf. Date accessed: July 3, 2020.

2. Richard Lapchick, 2019 Racial and Gender Report Card: College Sport, The Institute for Diversity and Ethics in Sport (Orlando: University of Central Florida, June 3, 2020): 54, https://43530132-36e9-4f52-811a-182c7a91933b.filesusr.com/ugd/7d86e5_d69e3801bb8146f2b08f6e619bcddf22.pdf. Date accessed: July 3, 2020. Information on African American youth in baseball is based on a 2020 update of a report on a 15-year survey of youth select baseball teams. The report was given at an academic conference as cited: David C. Ogden, “Major League Baseball and the Framing of African Americans.” Paper presented at the 28th annual Cooperstown Symposium on Baseball and American Culture, June 2, 2016, Cooperstown, NY.

3. For example, see David C. Ogden and Michael L. Hilt, “Collective Identity and Basketball: An Explanation for the Decreasing Number of African-Americans on America’s Baseball Diamonds,” Journal of Leisure Research 35, no.2 (2003): 213–22; David C. Ogden and Randall Rose, “Using Giddens’ Structuration Theory to Examine the Waning Participation of African Americans in Baseball,” Journal of Black Studies 35, no. 4 (2005): 225–45; Frank B. Butts, Laura M. Hatfield and Lance C. Hatfield, “African Americans in College Baseball,” The Sport Journal 10(2007), http://thesportjournal.org/article/african-americans-college-baseball. Date accessed: September 12, 2011; Joseph Cooper, Joey Gawrysiak, and Billy Hawkins, “Racial Perceptions of Baseball at Historically Black Colleges and Universities,” Journal of Sport and Social Issues 20, no. 10 (2012): 1–26; Brandon Brown and Gregg Bennett,”‘Baseball Is Whack!’: Exploring the Lack of African American Baseball Consumption,” Journal of Sport and Social Issues 39, no. 4 (2015): 1–21.

4. John McCarthy, telephone interview, January 20, 2012.

5. D. Randy Garrison, Terry Anderson, and Walter Archer, “Critical Inquiry in a Text-Based Environment: Computer Conferencing in Higher Education,” The Internet and Higher Education 2, nos. 2–3 (2000): 87–105.

6. John Dewey, “My Pedagogic Creed,” in Dewey on Education, ed. John Dewey (New York: Teachers College, Columbia University, 1959), 20.

7. Garrison, Anderson and Archer, “Critical Inquiry.”

8. Garrison, Anderson and Archer, “Critical Inquiry,” 101–102.

9. Garrison, Anderson and Archer, “Critical Inquiry,” 102.

10. Garrison, Anderson and Archer, “Critical Inquiry,” 102.

11. Tom Verducci, “Blackout: The African-American Baseball Player is Vanishing. Does He Have a Future?,” Sports Illustrated, July 6, 2003, 56–76.

12. David Canton, “Where Are All the Black Baseball Players?” U.S. News, July 10, 2017, https://www.usnews.com/opinion/op-ed/articles/2017-07-10/3-reasons-for-the-declining-percentage-of-black-baseballplayers-in-the-mlb. Date accessed: May 18, 2020.

13. Garrison, Anderson, and Archer, “Critical Inquiry,” 101.

14. Garrison, Anderson, and Archer, “Critical Inquiry,”101.

15. Garrison, Anderson, and Archer, “Critical Inquiry,” 99.

16. Garrison, Anderson, and Archer, “Critical Inquiry,” 89.

17. Garrison, Anderson, and Archer, “Critical Inquiry,” 100.

18. Brian Wilson and R. Sparks, “It’s Gotta Be the Shoes: Youth, Race, and Sneaker Commercials,” Sociology of Sport Journal 13, no. 4 (1996): 398–427; G.G. Watson, and R. Collis, “Adolescent Values in Sport: A Case of Conflicting Interests,” International Review of Sport Sociology 17, no. 3 (1982): 73–90.

19. Steven F. Philipp and Sherie Brezina, “Differences Among African Americans and Euro-Americans in Reasons for Sports Participation,” Perceptual and Motor Skills 95, no. 1 (2002): 184–86.

20. Steven F. Philipp, “Are We Welcome? African American Racial Acceptance in Leisure Activities and the Importance Given to Children’s Leisure,” Journal of Leisure Research 31, no. 4 (1999): 385–403.

21. Shaun M. Anderson and Matthew M. Martin, “The African American Community and Professional Baseball: Examining Major League Baseball’s Corporate Social-Responsibility Efforts as a Relationship-Management Strategy,” International Journal of Sport Communication 12, no. 3 (2019): 397–418, https://doi.org/10.1123/ijsc.2018-0157. Date accessed: May 18, 2020.

22. Monika Stodoloska, Iryna Sharaievska, Scott Tainsky, and Allison Ryan, “Minority Youth Participation in an Organized Youth Sports Program: Needs, Motivations and Facilitators,” Journal of Leisure Research 46, no. 5 (2014): 612–34.

23. Garrison, Anderson, and Archer, “Critical Inquiry,” 98.

24. Garrison, Anderson, and Archer, “Critical Inquiry,” 94.

25. Stodoloska, Sharaievska, Tainsky and Ryan, “Minority Youth Participation,” 617.

26. Brown and Bennett,”‘Baseball Is Whack!’,” 6.

27. Garrison, Anderson and Archer, “Critical Inquiry,” 98–99.

28. Garrison, Anderson, and Archer, “Critical Inquiry,” 98–99.

29. Richard Lapchick, The Complete 2020 Racial and Gender Report Card, the Institute for Diversity and Ethics in Sport (Orlando: University of Central Florida, March 4, 2021):10, https://www.tidesport.org/complete-sport. Date accessed: August 8, 2021. For further research on reasons for Africa American involvement in sport, see Othello Harris, “Race, Sport, and Social Support,” Sociology of Sport Journal 11, no. 1 (1994): 40–50; and Douglas Hartmann, “Rethinking the Relationship Between Sport and Race in American Culture: Golden Ghettos and Contested Terrain,” Sociology of Sport Journal 17 (2000): 229–53; Gerald Early, “Why Baseball Was the Black National Pastime,” in Basketball Jones: America Above the Rim, eds. Todd Boyd and Kenneth L. Shropshire (New York: NYU Press, 2000), 27–50.

30. Mark Armour and Daniel R. Levitt, “Baseball Demographics, 1947–2016,” Society for American Baseball Research, https://sabr.org/bioproj/topic/baseball-demographics-1947-2016. Date accessed: June 3, 2020. Armour and Levitt’s percentages for African American players in the major leagues are consistently lower than those of Richard Lapchick’s. Armour and Levitt surveyed the race of the approximately 11,000 MLB players on rosters between 1947 and 2016. As an example of the differences, Armour and Levitt found that 6.7 percent of those on the 2016 rosters, the last year they surveyed, were African Americans, compared with 8.3 percent reported by Lapchick. Lapchick’s percentages include “Blacks or African Americans,” while Armour and Levitt label their numbers as “African Americans.” Lapchick does not define “Blacks” in his 2020 Racial and Gender Report Card.

31. Lapchick, 2020 Racial and Gender Report Card: Major League Baseball, 36. Armour and Levitt’s research, however, shows that the percentage of MLB players who were African American varied between 7.1 and 6.7 percent from 2009 to 2016.

32. Lapchick, 2019 Racial and Gender Report Card: College Sport, 54.

33. Ogden, “Major League Baseball and the Framing of African Americans.”

34. “Omaha Slumpbuster Tournament,” Triple Crown Sports, https://www.omahaslumpbuster.com. Date accessed: October 1, 2020. In 2019, 736 teams participated in the Omaha-area tournament.

35. Armour and Levitt, “Baseball Demographics, 1947–2016.”

36. David C. Ogden, “The Welcome Theory: An Approach to Studying African-American Youth Interest and Involvement in Baseball,” Nine: A Journal of Baseball History and Culture 12, no. 2 (2004): 114–22; Les Edgerton, Perfect Game USA and the Future of Baseball (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Co., Inc: 2009).

37. David C. Ogden and Kevin Warneke, “Theoretical Considerations in College Baseball’s Relationship with Youth Select Baseball,” Journal of Sport Behavior 33, no. 3 (2010): 256–75. For further discussion on the link between youth elite baseball and college ball, see Charles Hallman, “Baseball is as White as Ever,” Minnesota Spokesman-Reporter, June 12, 2019, https://spokesman-recorder.com/2019/06/12/baseball-still-as-white-as-ever. Date accessed: October 1, 2020; Edgerton, Perfect Game USA and the Future of Baseball, 39, 105–11; William C. Rhoden,”A Divide that Begins in Little League,” The New York Times, May 28, 2007, D2.

38. J.J. Cooper, Carlos Collazo, and Jared McMasters, “Draft System Has Pushed Teams To Pick More College Players,” Baseball America, June 7, 2019, https://www.baseballamerica.com/stories/draft-system-has-pushed-teams-to-pick-more-college-players. Date accessed: September 29, 2020.

39. Stodoloska, Sharaievska, Tainsky, and Ryan, “Minority Youth Participation,” 621.

40. Stodoloska, Sharaievska, Tainsky, and Ryan, “Minority Youth Participation,” 623.

41. Verducci, “Blackout,” 56–76.

42. Verducci, “Blackout,” 58.

43. Garrison, Anderson and Archer, “Critical Inquiry,” 102.

44. David C. Ogden, “Wanted: Pied Pipers to Lead African Americans to Baseball,” in African Americans: Reviving Baseball in Inner City, ed. Sharon T. Freeman (Washington, D.C.: AASBEA Publishers, 2008), 199–207.

45. John McCarthy, telephone interview, January 31, 2012.

46. Bradford William Davis, “Ex-Mets Manager Jerry Manuel Still Believes in a Better Major League Baseball,” New York Daily News, February 14, 2021, https://www.nydailynews.com/sports/baseball/ny-20210214-pvtgdjdo2nadpnihf5usmntbim-story.html. Date accessed: August 7, 2021.

47. Anthony Giddens, The Constitution of Society: Outline of the Theory of Structuration (Berkeley: University of California Press: 1984), 50.

48. Anderson and Martin, “The African American Community and Professional Baseball,” 408–09.

49. Anderson and Martin, “The African American Community and Professional Baseball,” 409.

50. Stodoloska, Sharaievska, Tainsky and Ryan, “Minority Youth Participation,” 620.

51. Stodoloska, Sharaievska, Tainsky and Ryan, “Minority Youth Participation,” 617.

52. Garrison, Anderson and Archer, “Critical Inquiry,” 95.

53. Garrison, Anderson and Archer, “Critical Inquiry,” 98.

54. Garrison, Anderson and Archer, “Critical Inquiry,” 95.

55. Brown and Bennett,”‘Baseball Is Whack!’,” 6.

56. Brown and Bennett,”‘Baseball Is Whack!’,” 6.

57. Jan Ove Tangen, “‘Making the Space’: A Sociological Perspective on Sport and its Facilities,” Sport in Society: Cultures, Commerce, Media, Politics 7, no.1 (2004): 42.

58. Garrison, Anderson and Archer, “Critical Inquiry,” 95.

59. Besides the previously cited work of Philipp, Brown and Bennett, Ogden, and Cooper, Gawrysiak and Hawkins, see Trevor Bopp, Robert Turick, Joshua D. Vadeboncoeur, and Thomas J. Aicher, “Are You Welcomed? A Racial and Ethnic Comparison of Perceived Welcomeness in Sport Participation,” International Journal of Exercise Science 10, no. 6 (2017): 833–44, and Tangen’s other 2004 article, “Embedded Expectations, Embodied Knowledge and the Movements that Connect,” International Review for the Sociology of Sport 39, no. 1 (2004): 7–25.

60. Garrison, Anderson and Archer, “Critical Inquiry,” 98.

61. Tangen, “‘Making the Space’,” 43.

62. Stodoloska, Sharaievska, Tainsky and Ryan, “Minority Youth Participation,” 626.

63. Stodoloska, Sharaievska, Tainsky and Ryan, “Minority Youth Participation,” 626.

64. Garrison, Anderson and Archer, “Critical Inquiry,” 101.

65. Lapchick, 2020 Racial and Gender Report Card: Major League Baseball, 3.

66. Shaun M. Anderson, “Diversity Outreach in Major League Baseball: A Stakeholder Approach” PhD diss., West Virginia University, Morgantown, 2016, Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports (5102), https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/5102, 75. Date accessed: May 18, 2020. See also Anderson and Martin, “The African American Community and Professional Baseball,” 411–12, and Maury Brown, “How Major League Baseball Lost the Soul of Baseball,” Forbes, June 5, 2020, https://www.forbes.com/sites/maurybrown/2020/06/05/how-majorleague-baseball-lost-the-heart-of-baseball/?sh=37c813c549a. Date accessed: October 1, 2020. Brown argues that any gains in African American RBI participants entering the professional baseball ranks could be offset by the downsizing of the minor leagues and MLB draft and the subsequent loss of college baseball scholarships.

67. Lapchick, 2020 Racial and Gender Report Card: Major League Baseball, 9. Lapchick believes the MLB draft offers encouraging signs that the number of African Americans in the majors could be on the upswing. In 2018, almost 17 percent of the first 78 draft selections were “African-American/Black/African-Canadian.” Between 2012 and 2020, almost 18 percent of first-round picks were “Black or African American.”