Jackie Robinson and Jazz: Stealin’ Home

This article was written by Steve Butts

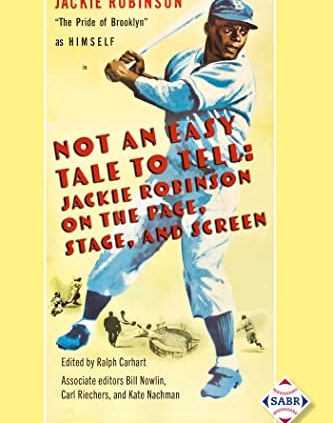

This article was published in Not an Easy Tale to Tell: Jackie Robinson on the Page, Stage, and Screen (2022)

The final performance of Stealin’ Home, featuring Bobby Bradford (cornet), Chuck Manning (tenor saxophone) and Vinny Golia (bass saxophone). (Courtesy of Jon Leonoudakis)

Jazz and baseball are two distinctly American forms of entertainment which have close ancestors that originally began in Europe, but were probably not recognizable as either jazz music or the game of baseball (as we know it) until they were each imbued with their own respective uniquely American character. This American character is something intangible that seemingly comes from America’s ability to quickly combine, incorporate, and alter older ideas while simultaneously producing newer ones. “Both uniquely American innovations, the history of jazz and baseball are intertwined. The word ‘jazz’ got its start in baseball; it was the early 20th century baseball term for ‘pep, energy’ before it became the term for the new frenetic style of music,” notes historian Shakeia Taylor.1

This “frenetic style of music” and propulsive pastoral game each arguably achieved their cultural high-water marks in New York City almost simultaneously in 1947, when Jackie Robinson integrated major-league baseball with the Brooklyn Dodgers. He immediately brought a decidedly new style of “pep, energy” in his brand of play. This all would seem to be more than just a coincidence, in a rapidly changing world.

Both baseball and jazz share the capabilities of being excellent vehicles for idiosyncratic, individual expression while often reflecting the harmonious, synchronous beauty of collaboration and teamwork. Robinson, with his military experience and extensive sports background, could likely see the delicate balance between the individual and the team. The whole might be greater than the sum of its component parts in some cases, while in others the single best talent prevails over all, because that talent is so decidedly sublime when compared to other competitors. It only made sense that with his awareness, and the aforementioned linkages between the game of baseball and jazz music, that he would also eventually become a fan of that music form.

According to journalist Michael G. Long, “Robinson and his wife were jazz enthusiasts who personally knew some of the famous musicians of their day. With help from their friend Marian Logan, a former jazz singer, the Robinsons soon put together an impressive lineup of jazz artists who agreed to play [a benefit concert on their property in Stamford, Connecticut] for free. Meanwhile, handy neighbors erected a canopied bandstand.”2 This initial event, in 1963, was successful enough that it encouraged the Robinsons to host numerous concerts, with proceeds raised for several charitable causes and civil rights organizations each time. After her husband died in 1972, Rachel hosted the concert annually, with the majority of the proceeds going to the Jackie Robinson Foundation, which grants scholarships to talented minority students. Sharon Robinson (Jackie and Rachel’s daughter) now runs the Jackie Robinson Foundation and helps produce the concert.3

The Robinsons were resourceful in their philanthropic efforts and were committed to help in any way they could. Still, jazz had a compelling allure when it came to supporting the Civil Rights movement. According to Rachel Robinson, “Jazz is the perfect medium to reflect life and the need people have to improvise and transcend barriers.”4

Spending much of his young life fighting personal battles that placed him squarely in the middle of the fight for social justice only emboldened and further energized Jackie Robinson to do whatever he could to support those pressing for social change, especially for those in the Civil Rights movement. These concerts and their proceeds initially were intended to help in the defense of several members of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s organization) who had recently been arrested during the Birmingham, Alabama campaign.

In 1962, Martin Luther King, Jr. recognized the importance of Jackie Robinson as an energetic forerunner to the continually emerging civil rights movement. “(He) [Robinson] was a sit-inner before the sit-ins, a freedom rider before the Freedom Rides,” King said.5 The year 1963 brought a further coalescence of the Robinsons’ role in the movement.

As civil rights demonstrations escalated at lunch counters and in segregated businesses, Robinson was further compelled to directly show his support for the movement. He said, “Whenever and where in the South the leaders believe I can help, just the tiniest bit, I intend to go.”6

On August 28, 1963, two months after the first “Afternoon of Jazz,” the Robinsons were a part of the March on Washington, where Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. gave his iconic “I Have a Dream” speech. Years later, when he recalled that day, Robinson wrote: “I have never been so proud to be a Negro. I have never been so proud to be an American.”7

***

In continuation of the larger historical legacy of the Robinsons’ philanthropy, in 2019 a collaborative enterprise began to germinate, one that would celebrate the life and legacy of Jackie Robinson in both baseball and jazz. In December of 2018, Terry Cannon and his wife Mary ran into jazz cornetist/trumpeter Bobby Bradford at their local bank. Cannon, who had been diagnosed recently with cancer, had an idea.

“Right away, Terry told him about his health situation and asked, ‘Bobby, if I survive my upcoming cancer (bile duct) surgery, would you be interested in composing a musical suite on the life of Jackie Robinson?’” according to Mary. “It’s going to be his centennial year. There was an immediate answer, ‘Yes!’ and straight away, Bobby was humming and singing, ‘Robinson, Rob-in-son.…’”8

Cannon was the director of both the Baseball Reliquary and the Institute for Baseball Studies at Whittier College in Whittier, California. Per their mission, the Reliquary is a nonprofit educational organization whose goal is to foster an appreciation of American art and culture through the prism of baseball history, and to explore the national pastime’s unparalleled creative possibilities.

“In 2018 the centennial anniversary of Robinson’s birth loomed, and Cannon was unsure about what the city of Pasadena might plan, so he doubled-down on his own brainstorming.”9 Cannon was increasingly feeling the need to step up and do something as a concern grew over a lack of plans.

In keeping with the Baseball Reliquary’s mission statement and its director’s ability to tell the part of the story that often went untold, Cannon’s mind sprang into action. “We had never commissioned a musical project before,” said Cannon. “I knew that Jackie and his wife Rachel loved jazz so it hit me that this might be something that would be meaningful.”10

Cannon had spent many years fostering the arts and music in Pasadena. He wrote about jazz for a local paper and acquired a massive collection of jazz LPs. He had attended lots of musical performances and had previously developed a relationship with Bobby Bradford. He also had started the Pasadena Film Forum (which became the Los Angeles Film Forum) and supported other fine arts.

Cannon’s audacious ability to organize and coordinate came from his considerable personal talents and the ability to inspire others to get behind whatever he was doing. As a young man, reading Bill Veeck’s Veeck – as in Wreck remained a formative and lasting influence.11 The Detroit-born Cannon’s outsider vision of baseball and his attraction to one of the true rebels and rabble-rousers would later offer a prime example of what an inductee to the Reliquary’s Shrine of the Eternals might be: an iconoclast with both a sense of humor and a sense of purpose. Veeck was the second major-league baseball owner (and the first in the American League) to integrate after Jackie Robinson, by adding Larry Doby and Satchel Paige.

2019 was a major year for Cannon because the Baseball Reliquary had also commissioned an art triptych commemorating the 100th anniversary of Rube Foster’s forming the Negro Leagues at the Paseo YMCA in Kansas City, Missouri, as depicted by Greg Jezewski, a work entitled The House That Rube Built. Commissioning Stealin’ Home, the eventual title of the finished jazz piece, would be another major step for fostering further creativity in the community.

Enter Bobby Bradford. Not only did he have considerable musical and creative talents, he also had valuable life experiences as someone who had also served in the military and grew up in an America that offered far less opportunity for African Americans. He witnessed first-hand and directly felt the changes that Jackie Robinson was bringing about.

“Seventh grade. When black wasn’t beautiful. There was no basketball, no community baseball. But in 1947, when Jackie Robinson joined the Brooklyn Dodgers? We were all cued up for that,” remembers Bradford. “He was a rebel. We had our eye on him. All Black America had their eyes on him.”12

Bradford also had his eyes on a career in jazz that brought him to Los Angeles and eventually Robinson’s alma mater, Pasadena City College, as a music educator. Bradford possessed a bit of Robinson’s rebellious spirit, being right there at ground zero with sax player Ornette Coleman at the birth of free jazz, which expanded jazz musicians’ possibilities for creative freedom without an imposed musical structure. Bobby was one of a select few performers who grasped Ornette Coleman’s harmolodic concept that offered even more unfettered freedom of expression to musicians. When I talked with Bradford, we discussed this in the context of a musical group playing like a team, where each performer was like a player.13

Cannon’s Baseball Reliquary co-conspirator Albert Kilchesty spoke further, “On the face of it, Branch Rickey—the baseball Mahatma—and Sonny Rollins—saxophone colossus—would appear to have nothing in common except for knowing Jackie Robinson, but each blew the same message: Luck is the residue of design. Actually, Rickey said that and Rollins intuitively knew that which is why he spent so many of his dark, wee hours alone, standing on or pacing around the pedestrian walkway of the Williamsburg Bridge, practicing—always practicing, always thinking, always chasing excellence. Each different man understood that without steady, proper preparation for the moment—to react to a crack of the bat, to riff breathtaking improvisational phrases—the outcomes will always disappoint. America’s Game, at its highest level, and American Art Music, at its dizziest height.”14

Cannon’s not being particularly didactic about the project was also helpful for Bradford. “So you do know what kind of music I play,” Bradford recalled, rolling into a chuckle. “Terry reassured me, ‘I don’t want something necessarily sweet and romantic,’ he told me. ‘I want something how you do something.’”15

The Baseball Reliquary’s proximity to Los Angeles and Robinson’s Pasadena home had made Robinson and the Dodgers prominent in many of the Baseball Reliquary’s past programs. Two of its relics, the Ebbets Field Cake and Michael Guccione’s Jackie Robinson icon painting, can be viewed at the Jackie Robinson Center in Pasadena. When the social services center opened in 1974, it was the first public facility in Southern California to be named after Robinson. Both Rachel and Jackie Robinson have also been inducted into the Baseball Reliquary’s “Shrine of the Eternals,” or “The People’s Hall of Fame,” as it was referred to by Shrine-inductee Jim Bouton.

During their first Shrine of the Eternals ceremony in 1999, Terry Cannon read a note of encouragement written decades earlier by Robinson to Dock Ellis, a charter member of the Shrine, encouraging Ellis’s continued bravery in standing up for racial equality. Robinson wrote, “I want you to know how much I appreciate your courage and honesty. In my opinion, progress for today’s players will only come from this kind of dedication. Try not to be left alone. Try to get more players to understand and you will find great support. You have made a real contribution. I surely hope your great ability continues. That ability will determine the success of your dedication and honesty.”16

Ellis’s induction was deeply moving. By connecting the Shrine of the Eternals directly with the cultural change previously spurred on by Robinson’s integration of major-league baseball with Robinson’s note of encouragement, it showed that these processes of social change are not frozen in time but are part of a larger continuing and ongoing social justice project. Composing a thematic piece to mark the 100th birthday of Jackie Robinson and the travails that he faced further extended that project.

The jazz septet (Bobby Bradford and Friends) itself has a progressive feel, both in the touches of free jazz soloing and in the densely arranged Minguslike ensemble sections which drive the music with considerable power and emotional voicing. Bradford’s challenging imprint is definitely there.

I talked with Bobby Bradford about composing the songs for the recording and it was an enlightening experience. The 87-year-old submerged himself further into several defining moments of Robinson’s life, trying to understand his thoughts and feelings about overcoming the obstacles that were so often placed before him in his personal and professional life as a Black man in America. Bradford had never been commissioned to compose a thematic piece before and he took the challenge very seriously and did considerable research on the life and career of Robinson.

Until the 2019 thematic composition of Stealin’ Home began, there had only been a select handful of songs written about Jackie Robinson, most famously Buddy Johnson’s “Did You See Jackie Robinson Hit That Ball?” There were also lesser-known songs by rock band Everclear and folk performer Ellis Paul, as well as songs entitled “The Jackie Robinson Boogie” and “Jackie Robinson Blues,” according to the Library of Congress. Nikki Giovanni has also written a Robinson poem entitled “Stealin’ Home.”17

One thing that I noticed and asked Bradford about was the superficial similarity between Stealin’ Home and the old gospel standard, “Steal Away,” which had a cultural connection to the Underground Railroad during the United States Civil War. Bradford responded that he had given it some superficial consideration but excised the idea when it became clear that it was not fitting into his broader conception of the Robinson piece.18

The songs focus on pivotal stages of Robinson’s life and reflect his taking the agency of choosing his own path, despite the many obstacles placed before him. The first cut, “Lieutenant Jackie,” features a martial, structured beat that becomes looser as time goes on, presumably as Robinson has a true assessment of his surroundings and feels more comfortable about his place within them. The song also deals with Robinson’s experience as an Army officer and the events of his court martial.

William Roper’s spoken section near the end of that selection highlights the ambivalence of serving one’s country yet eventually returning to civilian life as a second-class citizen. Bradford draws from his own personal life experience as a military man in this section, too. He recounted the tale of the time a service member had died and his family requested military buglers to play for the funeral. He and another bugle player (who was White) arrived to play for the funeral and the family immediately protested Bradford’s presence because he was an African American.19

The next song, “Up From The Minors,” represents the confusion and anguish of being the first African-American major leaguer, asked to shoulder considerable enmity with an elevated sense of grace. This is the most free and chaotic composition, with the crying swirl of reeds and Bradford’s vocal mimicking trumpet. To Bradford’s credit, he deftly balances raucous and unsettling sections with more conventional sections, which seems to restore order and security for the listener. Bradford also had thought about the Robinsons’ first spring training, when they were unable to make their entire flight to Florida, after the plane stopped to refuel in New Orleans and they were removed just because they were African American.

“Stealin’ Home,” the song that gave the album its title, represents Jackie at the peak of his powers, exuding mental confidence and playing with his own special flair. People inspired by Robinson’s life often look to this event as a particularly symbolic and defining moment in his career.

The final performance of Stealin’ Home, featuring Don Preston (piano), Henry Franklin (bass) and Tina Raymond (drums). (Courtesy of Jon Leonoudakis)

While researching for the album, Bradford considered the irony of Robinson finally getting his chance in the major leagues in the song, ”0 for 3,” only to go 0-for-3 in his first game (with a sacrifice and scoring one run after taking a walk). All of Black America was paying attention and hoping for something dramatic. It was very important and emblematic that Robinson had found a way to contribute, even if he did not have his best game.

Talking with Bradford, we mutually agreed that even if Robinson had gone 3-for-3 that day, there would have likely been several fans critical of his performance as a means of demeaning him.

The album closes with a more somber and reflective tone on “High and Inside,” seemingly indicating that Robinson was realizing that even though he might be ending his highly impactful playing career, societal changes were only just beginning.

In all, there were five Jackie Robinson Centennial concerts presenting Stealin’ Home. Notably, several of the performances were opened by jazz vocalist Byron Motley, who is the son of Negro League umpire Bob Motley. The shows were well attended and favorably received. Greg Jezewski remembered going early to help Cannon with the first concert, which he said Cannon had fully under control (as he generally did). Cannon, a production veteran, still looked and acted like he had butterflies, hoping that the event would be well attended and go on nearly without a hitch.20

“The event was an extraordinary celebration of an extraordinary man, made even more meaningful by taking place in Jackie’s adopted hometown,” said Kathy Robinson-Young, Jackie’s niece. Robinson-Young added, “Bobby Bradford’s stellar group blew the house away with their musicianship and unique take on Jackie’s journey. One piece about Jackie’s rise through the minor leagues was an abstract montage of the ugly experiences Jackie faced on his way to Brooklyn. It was unsettling and remarkable. This event is yet another chapter in the brilliance of the Baseball Reliquary, who continue to produce some of the most remarkable events and experiences celebrating the human side of baseball and its impact on culture.”21

There is also a burden that must be carried in every social legacy. Bradford and I discussed Robinson’s burden. In a previous interview with the Los Angeles Times, Bradford mentioned being a youngster and seeing his hero Louis Armstrong perform. He said that Armstrong played craps and put pomade in his hair and acted more naturally around other African Americans. But as soon as a White person entered the room, he put on his “mask.”22

This “mask” was a way of both protecting himself and meeting expectations for the White folks. Not only that, it was giving them an acceptable caricature of himself. It was the dichotomy of balancing your public and private personas, except in this case, your genuine persona is always muted in deference to the members of another race.

I asked Bradford whether having to carry this “mask” as an African American man could cause mental or physical damage and Bradford responded that he could not “speak with any authority on the physical or mental impact except (in) my own experience. The mask requires a lot of psychic energy at a price.”23

Cannon’s dying only 10 months after the Stealin’ Home concerts reminds us of that commitment to the ongoing project for social change. Bradford has since retired from teaching and has performed sparingly as the Covid-19 pandemic continues to limit and inhibit live performances nearly everywhere. I asked Bobby Bradford about his thoughts about his partnership with The Baseball Reliquary and the Cannons. He responded that “In times like these of racial, cultural and religious strife, people like Terry and Mary Cannon are reminders that the world is still full of wonderful people.”24

STEVE BUTTS is a long-time book and record store employee who is in his first year as a member of SABR. He is also is a Facebook page administrator for The Baseball Reliquary and Institute for Baseball Studies. He collects custom art cards with a growing personal collection focused upon “The King” Eddie Feigner.

Author’s Note

A full performance of Stealin’ Home can be viewed at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mAlrpnHLwek

Notes

1 Shakeia Taylor, “Prospectus Feature: Baseball and Jazz,” Baseball Prospectus, February 6, 2019, https://www.baseballprospectus.com/news/article/46970/prospectus-feature-baseball-and-jazz/

2 Michael G. Long, “The Undefeated, Music to his ears: How Jackie Robinson’s love of jazz helped civil rights movement,” theundefeated.com, April 15, 2020. https://theundefeated.com/features/how-jackierobinsons-love-of-jazz-helped-civil-rights-movement/

3 Michael G. Long.

4 Michael G. Long.

5 “Robinson, Jackie,” The Martin Luther King, Jr. Encyclopedia, The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute, Stanford University, https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/encyclopedia/robinson-jackie

6 Christina Knight, “Five Important Years in Jackie Robinson’s Life,” Thirteen, https://www.thirteen.org/program-content/five-importantyears-in-jackie-robinsons-life/

7 Christina Knight.

8 Mary Cannon, “Backstory: Thoughts from Mary Cannon,” liner notes for Bobby Bradford’s CD, Stealin’ Home, 2019, 1. The CD has never been commercially released.

9 Lynell George, “Play to Win!” liner notes to Bobby Bradford, Stealin’ Home.

10 Lynell George.

11 David Karpinski, Baseball Roundtable, https://baseballroundtable.com/the-baseball-reliquary/

12 Lynell George.

13 Bobby Bradford interview with Steve Butts, January 21, 2022.

14 Albert Kilchesty, friends-only Facebook post, May 16, 2020, Accessed February 4, 2022.

15 Lynell George.

16 David Karpinski, Baseball Roundtable, https://baseballroundtable.com/the-baseball-reliquary/

17 “Did You See Jackie Robinson Hit That Ball,” United States Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/collections/jackie-robinson-baseball/articles-and-essays/baseball-the-color-line-and-jackie-robinson/did-yousee-jackie-robinson-hit-that-ball/

18 Author interview with Bobby Bradford.

19 Author interview with Bobby Bradford.

20 Author interview with Greg Jezewski, January 19, 2022.

21 Terry Cannon, “Celebrating Jackie Robinson in Pasadena,” Face-book post, December 16, 2019.

22 RJ Smith, “An L.A. jazz legend pays homage to Jackie Robinson with a pitch from a library assistant,” Los Angeles Times, September 25, 2019. https://www.latimes.com/entertainment-arts/music/story/2019-09-25/bobby-bradford-jackie-robinson-stealin-home

23 Author interview with Bobby Bradford.

24 Author interview with Bobby Bradford.