Stolen Victories: Daring Dashes That Send the Fans Home Happy

This article was written by Jan Larson

This article was published in 2007 Baseball Research Journal

The slugger stands at the plate in the bottom of the ninth, the score tied. The crowd rises in anticipation. The windup. The pitch and…there it goes!

We’ve all seen them. Game-ending or “walk-off” home runs are shown on SportsCenter almost every night and many fans consider them to be among the most exciting plays in baseball. Of course, there are other ways to “walk off” the field. Some readers may recall Pirate pitcher Bob Moose’s walk-off wild pitch that scored George Foster to give the Reds the 1972 National League pennant, the walk-off walk by Andruw Jones off the Mets’ Kenny Rogers that won the deciding game of the 1999 NLCS for the Braves, and the unforgettable walk-off error by the Red Sox’s Bill Buckner in game six of the 1986 World Series.

Of all the ways a game-ending run may score, perhaps the most unexpected is by the steal of home. An adventuresome base runner using the element of surprise can win a game in a sudden and dramatic fashion. Chances are that you have not witnessed a major league walk-off steal. There have been only three in the past 31 seasons.

This author was fortunate enough to be in the stands at Royals Stadium (as it was then known) in Kansas City on August 17, 1976, as Hall of Famer George Brett broke from third as Indians reliever Dave LaRoche wound up in the 10th inning of a 3-3 game. Brett was two-thirds of the way to the plate before LaRoche noticed him and easily slid in under the pitch to score the winning run.1

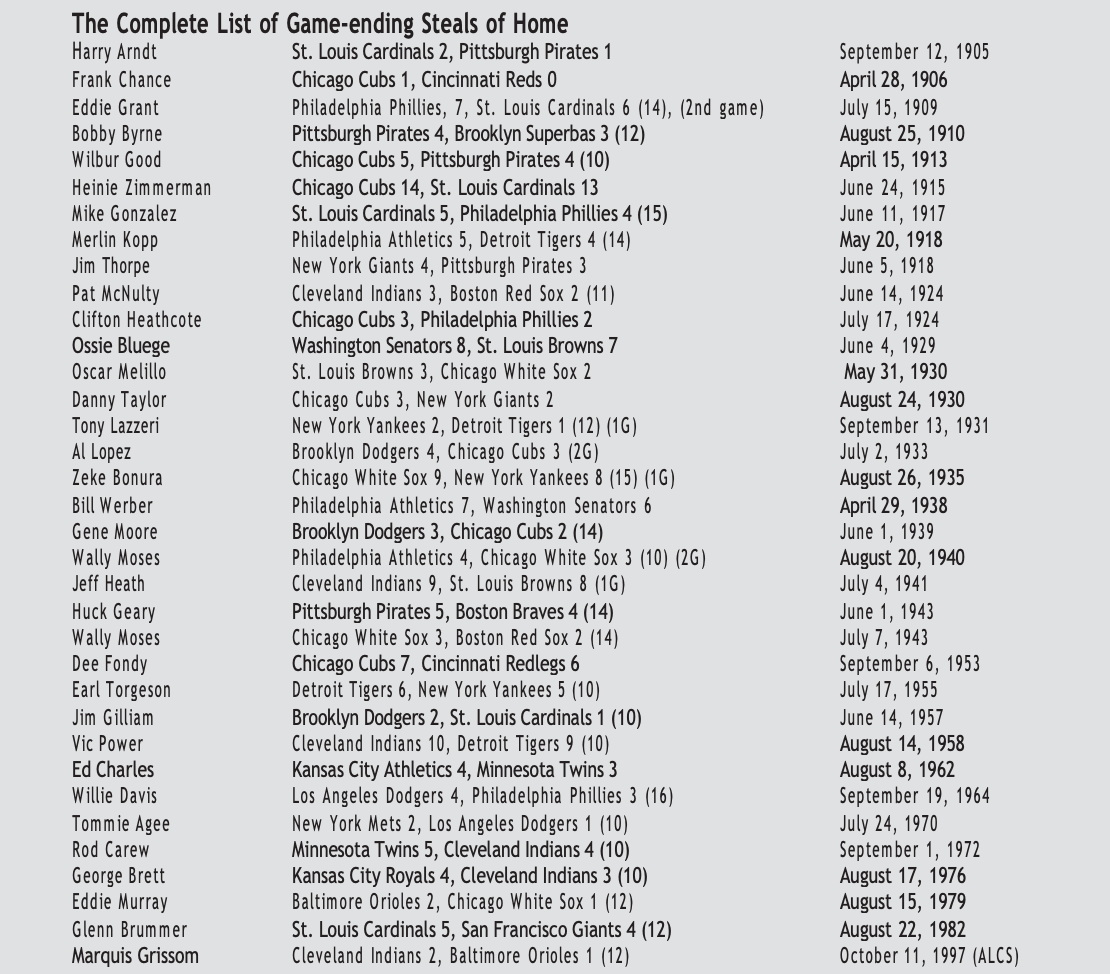

Since 1901, there have been 35 game-ending steals of home in the major leagues, but only eight in the post-1960 expansion era. The busiest decade was the 1930s with seven. There was just a single gameending steal in the 1980s, one more in the 1990s and none so far in the 21st century.

A few of the game-winning steals were executed by established base stealers. Rod Carew, Marquis Grissom, and Willie Davis all turned the trick, although Ty Cobb, the all-time leader in steals of home with 54, Rickey Henderson, the all-time stolen base leader (1,406 total steals but just four steals of home) and Jackie Robinson (19 steals of home), never accomplished the feat.

Three years removed from the 1969 season in which he stole home seven times (though none were game winners), Carew surprised the Indians with a 10th inning game-winning steal against reliever Ed Farmer on September 1, 1972.2 Carew finished his Hall of Fame career with 17 steals of home, the most for any player with a walk-off steal.

Grissom, then with the Indians, was on third with one out in the 12th inning of a 1-1 game in game three of the 1997 ALCS against the Orioles. With Omar Vizquel at the plate, the Indians attempted to squeeze home the winning run. Randy Myers’ pitch was in the dirt and scooted past catcher Lenny Webster as Grissom scored.3 The play was originally scored as a passed ball, and fans left Jacobs Field not knowing that they had witnessed something much more historic. The following day, citing rule 10.08(a), the official scorer changed the play and credited Grissom with a game-ending steal.4

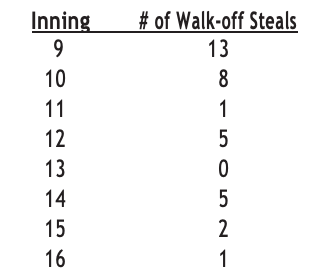

Of the 35 walk-off steals of home, 22 have occurred in extra innings. This may suggest that once a game goes into extra frames, it would be more likely that an intrepid base runner would attempt to win the game, but considering that walk-off steals can only happen in the ninth or later innings, the fact that 37% of them have occurred in the ninth inning suggests that the inning in which a courageous runner takes matters into his own hands is really not a factor.

Former Dodger Willie Davis holds the record for the latest game-winning steal of home, having used his legs to end a 16-inning game against the Phillies on September 19, 1964. In the 14th inning, Phillies outfielder Johnny Callison was caught stealing home when shortstop Bobby Wine failed to get the ball down on an attempted squeeze play, setting the stage for Davis to win the game two innings later. Davis reached on a two-out single, stole second, and advanced to third on a wild pitch, then raced home with the winner.5

That a player like Carew, with a history of stealing bases and stealing home, would pull off a game-winning steal is not terribly surprising, but there have been a few game-enders that were surprising even to the players that completed them. Six players that won a game by stealing home finished that season with fewer than five stolen bases. Two players that accomplished the feat finished their careers with fewer than five stolen bases.

Huck Geary played in just 55 major league games for the Pirates in 1942 and 1943, finishing with a career average of .160 and three stolen bases. In the 14th inning of a game against the Boston Braves on June 1, 1943, Geary was on third with the bases loaded and one out when he raced for the plate and scored under the tag of catcher Hugh Poland, giving Pittsburgh a 5-4 decision.

Glenn Brummer played for the Cardinals and Rangers in 1981-85, never appearing in more than 49 games in any season. Brummer, never mistaken for some of the speedsters on the St. Louis clubs of that era, stole just two bases during the 1982 season, finishing his career with four. Brummer entered the August 22, 1982, game against the Giants as a pinch-runner in the eighth inning and remained in the game to catch. After striking out in the 10th, Brummer singled to left in the 12th for his first hit since July 16. He advanced to second on a single and to third on an infield hit.

With two out and a 1-2 count on David Green, Brummer, noticing that Giants lefty pitcher Gary Lavelle was not paying attention to him, broke for the plate and slid under the tag of catcher Milt May, giving the Cardinals a 5-4 victory. The Giants argued that home plate umpire Dave Pallone had not called the pitch. Had it been a strike, the inning would have been over and the run would not have counted. Pallone indicated that he had, in fact, called the pitch a ball and thus the game was over. Brummer, apparently as surprised as anyone, remarked, “No one would have ever thought I would steal home in the major leagues, including me, especially to win a ball game.”6

Seven Hall of Famers have pulled off game-ending steals. In addition to the aforementioned Brett and Carew, Frank Chance of the Cubs, Tony Lazzeri of the Yankees, Al Lopez, of the Dodgers and Eddie Murray of the Orioles all took matters into their own hands to bring a game to conclusion. The seventh Hall of Famer isn’t enshrined in Cooperstown with the others. Instead, Jim Thorpe’s plaque is mounted in the Pro Football Hall of Fame in Canton, Ohio.

Thorpe played parts of six seasons with the New York Giants, Boston Braves, and Cincinnati Reds between 1913-19, appearing in just 289 games with a lifetime batting average of .252. Thorpe stole only 29 bases in his career, but the one on June 5, 1918, was the most memorable. With runners on first and third and two out, teammate Jose Rodriguez broke for second as Thorpe delayed a break for home. As Joe Wilhoit swung at and missed Pirate pitcher Wilbur Cooper’s first offering, Thorpe made his move. Catcher Walter Schmidt, bluffing a throw to second, fired the ball to Cooper, who inexplicably threw behind Thorpe to third baseman Bill McKechnie. McKechnie’s hurried throw home was in the dirt as Thorpe scored the game winner.7

With over 169,000 regular and post-season games played since 1901 and only 35 game-ending steals, it would seem unlikely that any player or pitcher would be involved in more than one. Wally Moses played 17 seasons for the Athletics, White Sox, and Red Sox, stealing a total of 174 bases, although he only stole six in 1940. On August 20 of that year, Moses beat the White Sox when he took advantage of a slow windup by Sox pitcher Thornton “Lefty” Lee to slide in with the winner in the 10th inning.8

Demonstrating that practice makes perfect, Moses became the only player in major league history to execute a second game-ending steal of home when he won a 14-inning game for the White Sox against Boston on July 7, 1943. Moses’s steal was so unexpected that Irving Vaughan’s game account in the Chicago Tribune stated that Moses was nearly in his slide before Red Sox pitcher Mace Brown had released the pitch.9

While Moses “perfected” the art of the walk-off steal, a pitcher whose career is most remembered for giving up a World Series home run is the only hurler to be on the mound for not one but two game-ending steals of home. Charlie Root spent 16 of his 17 major league seasons pitching for the Chicago Cubs and is most noted for giving up Babe Ruth’s legendary “called shot” in the 1932 World Series. Root entered the July 2, 1933, game against the Dodgers in the ninth inning in relief of starter Lon Warneke, attempting to preserve a 3-2 lead. After Brooklyn tied the game on a single by Ralph Boyle, Al Lopez clinched a doubleheader sweep for the Dodgers with a two-out theft under the tag of Cub catcher Gabby Hartnett.10

Root faced a similar situation six seasons later. On June 1, 1939, again against Brooklyn at Ebbets Field, Root entered the game in the eighth and held the Dodgers hitless until Gene Moore tripled with one out in the 14th inning. After two intentional walks, Root faced shortstop Leo Durocher. With the squeeze on, Durocher failed to make contact with Root’s offering but catcher Bob Garbark couldn’t hold the ball and by the time he recovered, Moore had scored the winning run.11 That game also featured a triple play, executed by the Dodgers in the 12th inning. Remarkably this was not the only game that featured both a walk-off steal and a triple play.

Pat McNulty, who spent five seasons with the Indians, had a game to remember on June 11, 1924. With McNulty on second and Charlie Jamieson on first in the fourth inning, Tris Speaker lined to Red Sox first baseman Howie Shanks, who stepped on the bag to double Jamieson, then threw to shortstop Dud Lee, doubling McNulty and completing the triple play. McNulty’s fortunes took a turn for the better when he tallied the winning run with a two-out steal of home in the 11th giving the Indians a 3-2 victory.12

Perhaps the most startling game-ending steal of home was by the Cleveland Indians’ Vic Power on August 14, 1958. Power played 12 seasons for four clubs and in 1958 split time between the Indians and Kansas City Athletics. Power was not a serious threat on the base paths, stealing just 45 bases while being caught 35 times during his career. He stole just two bases for the Indians in 1958. What made Power’s feat so remarkable was that those two stolen bases both occurred in the same game, and they were both steals of home! Power stole home in the eighth inning to give the Indians a 9-7 lead over the Tigers, and after Detroit tied the game in the ninth, Power won the game for the Tribe with a two-out steal in the 10th off Frank Lary. Power remains the only player since 1927 to steal home twice in the same game.13

No one can deny that the game has changed in recent decades. Unlike the years prior to the 1980s, starting pitchers now rarely pitch into the ninth inning (or later) when fatigue may result in a loss of concentration on base runners. Starters often do not pitch from the windup with runners on third, as in years past, and most relievers regularly pitch from the stretch position regardless of runners on base. Coupled with players making multimillion-dollar salaries unwilling to risk a three-way collision with ball and bat at home plate and so many managers managing “by the book,” the chances of the average fan seeing any straight steals of home, never mind a game ender, simply aren’t as great as in years past. Considering that the last game-ending straight steal of home occurred 25 years ago, it is possible that arguably the most exciting play in baseball history may have gone the way of the dinosaur.

(Click image to enlarge)

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to acknowledge the following SABR members who provided consultation and/or research assistance to the game-ending steals of home project: Lyle Spatz, Chuck Rosciam, Tom Ruane, Bill Deane, Jim Smith, Bill Gilbert, Monte Cely, Norman Macht, Gilbert Martinez, Patrick Gallagher, John Delahanty, Rod Nelson, Frank Vaccaro, and Jim Sweetman. Special thanks to Dave Smith. Without Retrosheet, this research would have been virtually impossible.

Notes

- “Brett Steals One for the Royals, 4-3,” Los Angeles Times, August 18, 1976.

- “Twins Edge Tribe,” Washington Post, September 2, 1972.

- Jack Curry, “Indians Defeat the Orioles in a Wild One on a Disputed Passed Ball in the 12th,” New York Times, October 12, 1997.

- “Game 3 Scorer Makes Change,” New York Times, October 13, 1997.

- “W. Davis Steals Home in 16th to Beat Phils,” Chicago Tribune, September 20, 1964.

- Washington Post, August 23, 1982.

- “Giants Crash Their Way to Victory Over Pirates by a Ninth-Inning Rally,” New York Times, June 6, 1918.

- Irving Vaughan, “White Sox beat A’s in 9th, 6-1; Lose in 10th, 4-3,” Chicago Daily Tribune, August 21, 1940.

- Irving Vaughan, “Moses Steals Home in 14th; Sox Defeat Boston, 3-2,” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 8, 1943.

- Roscoe “Dodgers Take Two from Cubs, 7-3, 4-3,” New York Times, July 3, 1933.

- Edward Burns, “Dodgers Beat Cubs in 14th, 3-2; Make Triple ” Chicago Daily Tribune, June 2, 1939.

- “Steal by M’Nulty Wins for Indians,” New York Times, June 15, 1924.

- “Stealing Home Base Records,” Baseball Almanac, https://baseballalmanac.com/recbooks/rb_stbah.shtml.