Strong Down the Stretch: Warren Spahn’s Fantastic Finishes

This article was written by Eric Marshall White

This article was published in 2003 Baseball Research Journal

It seems unlikely that anything new could be said about the storied pitching exploits of Warren Spahn, who put together the greatest career by any left-handed pitcher during the postwar era. He is remembered not only for his excellence, but also for his consistency, having won 20 or more games in a season 13 times, as well as for his longevity, having pitched no-hitters at the ages of 39 and 40 and becoming the oldest 20-game winner at 42. He led his league in victories eight times, won the ERA title in three different decades, and took the Cy Young Award in 1957 (he would have won three or four more had the NL award been around as long as he was). Despite devoting three years to military service in World War II, he finished with a lifetime total of 363 wins. Clearly, Spahn belongs on the all-time pitching staff-but this is hardly news

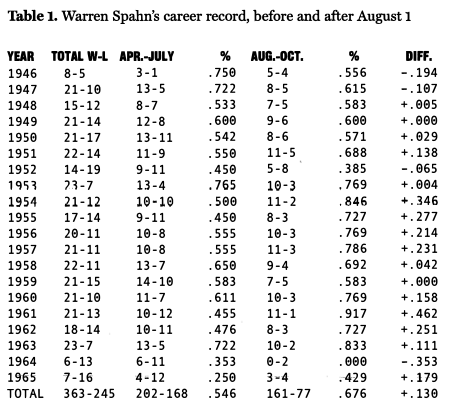

However, one particularly amazing aspect of his performance seems to have escaped notice entirely: Warren Spahn may have been the greatest pitcher of all time when it came to improving his performance down the stretch run in August and September. I’ve read countless anecdotes and analyses concerning Spahn during the past 30 years, but not once have I seen one mention of his incredible career-long pattern of getting hot down the stretch. In the zone, turning it up a notch, huge in the clutch, saving his best for last – whatever you want to call it, Spahn became a different pitcher after August began, raising the relative level of his performance to a degree that is probably unparalleled in the history of the sport. His career numbers before and after the first of August are a revelation.

Mark those career-winning percentages down in your mind: Spahn was 130 percentage points higher in the late going. Certainly, no clutch hitter so consistently raised his stretch-run numbers to such a degree over two decades. For a team, Spahn’s sudden improvement is like starting 53-44 before going on a 44-21 tear to finish with 97 wins. A team playing like Spahn’s first four months might sneak into a wild-card slot once in a while, but a team keeping pace with Spahn’s final months all year would rank among the greatest.

Did Spahn’s late-season dominance make him more valuable than his overall 363-245 record would suggest? I’m not convinced that performing well down the stretch is particularly important. It certainly sounds good to say, “He gets hot when it counts,” but when exactly doesn’t it count? Mr. Steinbrenner can call an expensive player “Mr. May” all he wants, but those winning hits in May count just as much toward the standings as those that come in September. As Rocky Bridges rightly said of the Brooklyn Dodgers after Bobby Thomson’s home run won the 1951 playoff for the Giants, “We lost the pennant on Opening Day.”

Still, there is an emotional difference that intensifies those late summer games as the players become more aware of the standings and begin to feel more clarity of purpose. It may not be more important to win late in the season, but perhaps it is more difficult. I would venture to guess that a lot more pennants are won with hot Septembers than with cold ones.

To put it another way, a less worthy team is more likely to collapse late while a true winner is able to play well under the emotional pressure as time runs out. Spahn’s teams just missed a couple of pennants they could have won, but that wasn’t his fault. Let’s look more closely at how he did down the stretch through the years:

1946: Nothing to attract notice, just a solid 5.4 finish.

1947: His 8-5 finish would have been even better if not for 1-0 and 2-0 losses to Brooklyn and Cincinnati. Still, he won three shutouts (including a 1-0 beauty against the Cubs on September 14) while allowing only five runs in his six starts during September.

1948: The famous refrain “Spahn and Sain and pray for rain” has drawn many critics, who cite the fact that at 15-10, Spahn’s winning percentage was lower than that of his teammates. However, Boston Post writer Gerry Hern had ample reason to wax poetic that September. While the other Braves pitched nearly as well as Sain and Spahn, it was not nearly as often. Sain and Spahn dominated Boston’s run of 14 wins in 15 games that month, at one point winning 10 straight decisions (four by Spahn). Between September 6 and 18, the duo pitched eight of Boston’s 10 games, winning all of them (four wins each). That streak started with Spahn’s 14-inning, 2-1 masterpiece over Brooklyn, in which he picked Jackie Robinson off first base twice. It was one of five late summer games that he won with only two runs of support. He lost his last two starts, but the pennant had been won.

1949: Although Brooklyn came back to beat him twice in their September run for the pennant, Spahn’s 9-6 finish was highlighted by a 4-0 win over Brooklyn’s Preacher Roe on August 20 and a 1-0 masterpiece over Philadelphia’s Robin Roberts on September 10.

1950: Spahn’s 8-6 finish was only a slight improvement on his 13-11 start, but his record rose to 5-1 in September.

1951: With a ledger of 11-5, this stretch run marked Spahn’s first truly outstanding finish. After he lost 1-0 to the Phillies on August 7, the Braves scored a grand total of three runs for him in three close losses to the Giants, who were busy winning 37 of their last 44 games. The final defeat was a critical 3-0 win for Sal Maglie on the season’s next-to-last day that helped set up the Miracle of Coogan’s Bluff.

1952: The dismal final season in Boston had few bright spots. Although he lost 1-0 to Brooklyn’s Carl Erskine on September 20, some consolation may have come from the fact that his final four victories were all shutouts, including his own 1-0 whitewashing of Cincinnati on September 9. To this point, Spahn’s lifetime record from August 1 stood at 53-39 (.576), very good, but just a shade above his overall record. His truly remarkable run was about to begin.

1953: As the Milwaukee Braves surprised everyone with their success, Spahn had the best start of his career (13-4) and his best finish to that point (10-3). He allowed only 11 runs during a 6-1 month of August, and following a 2-0 loss to Philadelphia, he won his last four decisions.

1954: After a lackluster 10-10 start, Spahn sizzled to a 11-2 record down the stretch. He won 11 straight games between July 18 and September 8, and won his last two starts of the year.

1955: Spahn followed up another slow start with a stretch run of 8-3. His last two losses were both by the score of 2-0.

1956: The southpaw carried the Braves during their pennant bid with another 10-3 finish. In September, while his teammates struggled to a 9-11 finish in games in which he did not work, Spahn held on for a 5-2 record-his final loss coming against the Cardinals in a 12-inning, 2-1 game on September 29.

1957: The pennant was Milwaukee’s in 1957, thanks in large part to the Cy Young Award winner’s 11-3 finish. He won nine straight decisions between August 6 and September 7, and his final defeat, another loss by shutout, came five days after Hank Aaron’s homer had clinched the pennant.

1958: Spahn got off to a 6-0 start, but cooled off to .500 over his next 14 decisions (including three shutout losses). He finished 9-4 during the last two months, including a typical 5-1 record in September as the Braves took their second straight pennant.

1959: Leading up to Milwaukee’s heartbreaking playoff loss to Los Angeles, Spahn contributed a 7-5 mark with a 4-2 record in September, including a victory over Robin Roberts in his season finale. Still, any improvement upon his season record of 0-5 versus the Dodgers could have made all the difference in the pennant race.

1960: With a 6-0 record in August, Spahn finished the season with another 10-3 run that included his first career no-hitter, a 4-0 masterpiece against the Phillies on September 16. His final three defeats all came at the hands of the world champions to be, Pittsburgh.

1961: On August 11, the 40-year-old won his 300th ball game, leveling his record at a respectable 12-12. He rallied to his greatest finish of all, an amazing 11-1 roll that included three September shutouts, highlighted by a 1-0 affair versus the Phillies on September 6. Milwaukee’s opponents scored 11 runs in the 11 wins. His only loss came after 10 straight wins, in a September 15 blowout against his future successor atop the pitching world, Mr. Koufax.

1962: Somehow, he did it again, finishing 8-3.

1963: The oldest 20-game winner in history, Spahn started off great (despite his famous 1-0 loss to Juan Marichal on July 2, when Willie Mays homered in the bottom of the 16th inning), and he finished even better at 10-2, with yet another 1-0 masterpiece versus Pittsburgh’s Bob Friend among his three September shutouts.

1964: With an 0-2 finish, Spahn’s great run was over.

1965: A 3-4 finish isn’t bad — for a 44-year-old!

Thus, we see that Spahn was a fantastic finisher, and not just because he finished 449 contests in his career and won 77 games after turning forty. For whatever reason, Spahn started his seasons relatively slowly but had a formidable late kick. I hesitate to speculate here but was it because he was unusually fit for his time, a marathon man able to outlast his tiring opponents late in the year? Even though Spahn was a perfect 7-0 in his late-season duels with the famously durable Robin Roberts, that explanation doesn’t sound quite right.

Isn’t it more likely that this pervasive trend of improvement related to Spahn’s well-documented pitching intelligence, which made him especially adept at solving problems over the course of the season with craft and guile? I will point out that the effect was barely perceptible during Spahn’s early years, but it intensified throughout his maturity.

Run support? I have the game scores for Spahn’s first 504 decisions (from 1946 to 1961), and the Braves averaged a composite 4.50 runs per game through July and 4.29 runs per game from August to the season’s end hardly the offensive push one might expect, given Spahn’s record. Milwaukee’s opponents scored 3.56 runs per game in Spahn’s starts through July, and only 3.03 runs there after. Spahn was magnificent down the stretch.

I imagine that a small handful of great pitchers may have compiled late-season winning percentages that were greater than Spahn’s, but I have yet to find anyone with a lengthy career that had such a large before-and-after differential.

At first glance, the candidates most likely to have exceeded his .676 late summer record were Whitey Ford, with his .690 overall percentage, and Lefty Grove, at .680 lifetime. Ford, though, was “only” 6-2 and 7-3 in the closing months of his 20-win seasons, so it’s hard to see where any truly gigantic finishes would be hiding.

Grove had several astounding finishes, and most likely exceeded Spahn’s .676 mark in the late going, but he could pitch like that all summer long, so I would not expect much of an early-late split. Indeed, the higher a pitcher’s lifetime winning percentage, the less likely he is to have run up a large differential: if Grove had compiled such a Spahnian split, his percentages would have been .629 before and .759 after August 1, and it’s hard to picture that happening over a couple of decades, given his starts of 17-2 in 1929, 21-2 in 1931, and 14-3 in 1938.

Thanks to Ronald A. Mayer’s Christy Mathewson: A Game-by-Game Profile, I was able to add up Matty’s totals: 233-105 before August 1 and 140-83 thereafter, a drop from .689 to .629, despite his huge 18-4 finish in the 1908 race.

Actually, the candidates most likely to match Spahn’s 130-point career differential are those with less stratospheric winning percentages, like Tom Seaver at .603 and Bob Gibson at .591 (although everyone remembers Gibby as better than that). However, a quick check shows that although Seaver put in a 10-1 finish for the Miracle Mets in ’69, he was lackluster in his last few seasons. Gibson, at his best in October classics, missed six weeks late in the 1967 race and finished only 7-4 in his famous ’68 campaign.

Walter Johnson? He, too, is unlikely to have approached Spahn’s feats. Although he finished his amazing 1913 season on a 13-2 run, he had started 23-5, making it a modest improvement only. We may read of his strong finishes in 1915 and 1924, but I suspect these were the exceptions, as his great 1912 season ended with a 4-5 slide, and the Big Train’s surprisingly mundane career road record of 184-162 (.532) probably prevented him from compiling too many two-month winning binges. His famous winning streaks of 1912, 1913, and 1924 started in late June and early July.

What sets Spahn’s record apart is that he won more than he lost from August onward for 11 straight seasons, and 17 times overall, most often by healthy margins. His winning percentage improved (or held even) late in the season 16 times, and he enjoyed five perfect Augusts, winning six without a loss in 1954, seven in 1957, six in both 1960 and 1961, and five straight in 1963. Perhaps most incredibly, his peak decade came when he was 32 to 42 years young.

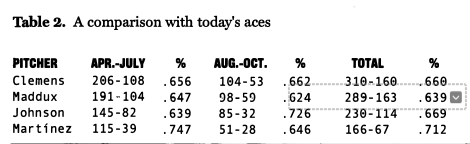

Among today’s greats, Roger Clemens has been the most consistent, Greg Maddux has faded slightly in the late going, Randy Johnson owns the largest positive differential so far (albeit in half as many stretch-run decisions as Spahn compiled), and Pedro Martinez has come back to earth from incredible heights (statistics through the 2003 season):

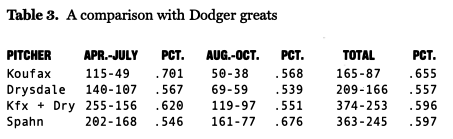

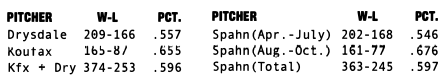

Perhaps the best way to put what Spahn did in the most meaningful context is to compare him to two of his contemporaries, Sandy Koufax (165-87) and Don Drysdale (209-166). Combined, the pair of Dodgers had a lifetime record of 374-253 (.596), which is directly comparable to Spahn’s 363-245 (.597) mark. However, whereas the two Dodgers got off to a better start than Spahn did, they fell way off the pace down the stretch:

What is amazing is that the careers of Koufax and Drysdale added together look a lot like Spahn’s splits:

Thus, in the early going Spahn was worse than Don Drysdale, a marginal selection for the Hall of Fame, while down the stretch he was better than Sandy Koufax, whom many consider the most dominant pitcher of their lifetime.

Although Spahn’s perennial surges seem to have evaded the notice of baseball writers and fans, they certainly merit close attention. Moreover, this data should encourage us to take another look at the career profiles of the other great pitchers, not only to see if anyone else had it in him to raise his performance to such dramatic heights down the stretch, but to better understand exactly how the Braves’ crafty lefty did it so often. For now, however, we may appreciate Warren Spahn’s greatness in a revealing new light — as the most fantastic finisher of them all.

ERIC MARSHALL WHITE, Ph.D., is curator of rare books at Bridwell Library, Southern Methodist University, in Dallas. His baseball card collection includes all the World Series starting lineups since 1951.