Stu Miller: The (Almost) Lost Oriole

This article was written by Wayne M. Towers

This article was published in The National Pastime: A Bird’s-Eye View of Baltimore (2020)

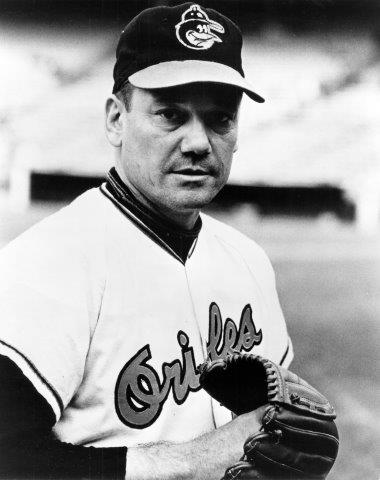

Although best remembered for a windswept balk during the July 11, 1961, All Star Game in San Francisco, Stuart Leonard “Stu” Miller put together a notable relief career with 153 career saves, 1952–68. He pitched primarily with the New York/San Francisco Giants (47 saves, 1957–62) and, perhaps surprisingly to some, with the Baltimore Orioles (99 saves, 1963–67).1

Although best remembered for a windswept balk during the July 11, 1961, All Star Game in San Francisco, Stuart Leonard “Stu” Miller put together a notable relief career with 153 career saves, 1952–68. He pitched primarily with the New York/San Francisco Giants (47 saves, 1957–62) and, perhaps surprisingly to some, with the Baltimore Orioles (99 saves, 1963–67).1

After a humble beginning with the St. Louis Cardinals and Philadelphia Phillies, Miller joined the Giants in New York, then traveled with them to San Francisco where his ill-fated balk took place at San Francisco’s Candlestick Park.2

Candlestick Park was the home of the San Francisco Giants from 1960 to 1999.3 It was named for its location at San Francisco Bay’s Candlestick Point, which was named in turn for a shorebird called the candlestick bird (Numenius americanus; status: threatened4), a long-legged, long-billed curlew about a foot tall. Considered a delicacy, the birds had been hunted out of the area, but the wind that remained took revenge on the human occupants. According to the National Weather Service, winds there could reach 62 miles-per-hour and shift 180 degrees during the times most games were typically played.5 Winds during game times were described as “cold,” “howling and swirling,” and “gale force” and with terms like “small craft warning,” “wind pixies,” and “devils at play.”6 One promotion awarded hardy fans a medallion called the “Croix de Candlestick” which proclaimed “Veni, Vidi, Vixi”(I came, I saw, I survived).7

“The Stick” aka “Windlestick” lived up to its wind-tunnel reputation that All-Star day. Miller was noted for his slight frame.8 Officially, he was listed at 5-foot-11 and 165 pounds, but observers have estimated him to be anywhere from 5-foot-8, 150 up to 5-foot-11 ½ and 175.9 He was thrown off balance after coming to the set position by a gust of wind. Despite a reputation for a deceptive pitching motion with a last-second head fake, he was called for a balk.10 In the hyperbole that followed, Miller was compared to windblown leaves, Dorothy and Toto in The Wizard of Oz, and later The Flying Nun (seriously11). Miller disliked the exaggerations. “The papers made it sound like I was pinned against the center-field fence,” he recalled.12 “You’d think I’d been blown into the Bay.”13

The less-remembered part of Miller’s career would come with the Baltimore Orioles. Hall of Famer Hoyt Wilhelm’s mid-career stay with the Orioles (40 saves, 1958–62) had cemented the bullpen in the Baltimore psyche at a time when bullpen work was viewed as a demotion.14 As manager Paul Richards was said to have pointed out, “Anyone can start a game but it’s important who finishes it!”15 Miller replaced Wilhelm’s (in)famous knuckleball with a variety of off-speed pitches described as somewhere between slow/slower/slowest and slow/slower/reverse.16 According to The Great American Baseball Card Flipping, Trading and Bubble Gum Book, “You had time for a coke and sandwich while waiting for his fastball to arrive.”17 His pitches were labeled change/change-up/change-up curve and a change-up off of a change-up, described as “moth and butterfly,” “banana ball and custard pie,” having “died from malnutrition,” “couldn’t break a pane of glass” nor a “wet paper sack.”18

During the 1960s, Miller’s Orioles performance, 99 saves between 1963 and 1967, was comparable to Wilhelm’s successes with the Chicago White Sox (99 saves 1963–1968). Miller helped Baltimore to the pennant in 1966 with a team-leading 18 saves and nine bullpen wins.19 But he was upstaged in the 1966 World Series by the bravura performance of Myron “Moe” Drabowsky aka Miroslav Drabowski.20

Known as a journeyman with control issues (1162 career strikeouts against 702 career walks), Drabowsky was more famous for pranks including hotfoots, firecrackers, phone calls, greased toilet seats, sneezing powder, goldfish in water coolers, and a towed airplane banner.21 Drabowsky also held the dubious distinctions of surrendering Stan Musial’s 3,000th hit and losing Early Wynn’s 300th win. Suddenly, he became a World Series legend. He relieved in the third inning of the first game, pitched 6 2/3 innings of one-hit, shutout ball, and struck out eleven, including six in a row. Perhaps humbly, Drabowsky stated “It’s about time I got in the books for something except the wrong end of the record.”22 His triumph was the only relief appearance in the entire Series for the Orioles, who swept the remaining three contests with complete-game shutouts.23 Afterwards, Drabowsky remained in Baltimore before finishing his career with three different teams.

Miller stayed one more year in Baltimore, then finished his career with the Atlanta Braves, but not before a final indignity in Baltimore. On April 30, 1967, lefty Steve Barber carried a no-hitter into the ninth inning. That inning Barber walked the first two batters, retired two batters, then uncorked a score-tying wild pitch. After walking a third batter, he left with an unenviable line of 10 walks, two hit batsmen, the aforementioned wild pitch, and a fielding error, but no hits.24 Miller entered the game and induced a surefire rally-ending ground ball, only to have an infielder drop the force-out for an error, allowing the winning run to score. Miller recorded the inning-ending out, but ended up with the dubious honor of sharing (with Barber) the second no-hitter loss in MLB history.25

In the end, Miller’s positive Baltimore legacy was being the Orioles team career saves leader with 99 until he was supplanted by lefty Felix Anthony “Tippy” Martinez, who earned 105 saves with Baltimore between 1976 and 1986.26

Even given the hard luck of the 1961 All-Star balk, the 1966 World Series absence, and the 1967 no-hitter loss, characterizing Stu Miller as a kind of Joe Btfsplk — cartoonist Al Capp’s comic character dogged by perpetual misfortune — would be a mistake. Overall, Miller’s record was far from undistinguished. His 153 career saves compare favorably with contemporaries Don McMahon (152) and Ted Abernathy(148), the first reliever to earn over 30 saves in a season. He also compared favorably with Hoyt Wilhelm himself in the 1960s (153 saves, 1960-1969). The key difference in Wilhelm’s career total is he added saves in the 1950s (58) and 1970s(17).27

In terms of career contemporaries, Miller, McMahon, Abernathy and 1960s-Wilhelm were on a tier just below the most successful relievers in the 1960s like Roy Face (191 career saves, 1953–69), lefty Ron Perranoski (178 career saves, 1961–73), and Lindy McDaniel (174 career saves, 1955–75). Taken together, this half dozen or so represented a relief pitching elite prior to the 1973 advent of the designated hitter.28

Although Miller tends to be remembered for the early part of his career with San Francisco rather than the latter years with Baltimore, during which he recorded 99 of 153 career saves, his selections to both the Giants Wall of Fame and the Orioles Hall of Fame preserve the memory of his achievements (and disappointments) for fans who sport the black and orange of the Orioles and Giants. Perhaps the sixtieth anniversary of his infamous All-Star balk (July 11, 2021) or the fifty-fifth anniversary of his lost no-hitter (April 30, 2022) could serve to revive his fame among fans who wear the colors of other teams. As he once reflected: “I guess that’s better than ‘Stu Who?’ I’d rather be remembered for something.”29

WAYNE M. TOWERS is a retired SeaWorld San Diego educator and a retired college professor. Prior to retiring, he also worked as a data analyst for the Oklahoman and Times daily newspaper and for multiple business research firms. His published work includes “World Series Coverage in the 1920s” (Journalism Monographs).

Sources

All career statistics from Baseball-Reference.com.

Photo: National Baseball Hall of Fame Library

Notes

1 Ron Firmite, “Gone with the wind?”, Sports Illustrated, September 01, 1986, Accessed January 14, 2019, https://www.si.com/vault/1986/09/01/113879/gone-with-the-wind-the-giants-want-out-of-blustery-candlestick-park-and-one-of-these-days-they-just-might-get-their-wish; John Thorn, The Relief Pitcher: Baseball’s New Hero, (New York: E.P. Dutton, 1979), 145.

2 Jim Brooks, ”Did Stu Miller Really Get Blown Off the Mound at Candlestick Park?”. KQED News, January 8, 2016., Accessed November 24, 2019, https://www.kqed.org/news/10400321/did-stu-miller-really-get-blown-off-the-mound-at-candlestick-park.

3 Alan Taylor, “The Lights Go Out on Candlestick Park,” The Atlantic, June 11, 2015, Accessed November 24, 2019, https://www.theatlantic.com/photo/2015/06/the-lights-go-out-on-candlestick-park/395633/.

4 “Candlestick Bird: Numenius americanus,” Project Noah, Accessed January 26, 2020, https://www.projectnoah.org/spottings/2088457561; “Long-billed Curlew: Numenius americanus,” International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List, Downloaded January 26, 2020, https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/22693195/93390204#taxonomy.

5 Firmite, “Gone with the wind?”

6 Mark Byrnes, “Goodbye, Candlestick Park (Finally)”, CityLab, Accessed November 24, 2019, https://www.citylab.com/design/2015/02/goodbye-finally-candlestick-park/385232/; “Candlestick Park/3Com Park Historical Analysis,” Baseball Almanac; Brooks, ”Did Stu Miller Really Get Blown Off the Mound at Candlestick Park?”; Firmite, “Gone with the wind?”

7 Byrnes, “Goodbye, Candlestick Park (Finally).”

8 Brooks, ”Did Stu Miller Really Get Blown Off the Mound at Candlestick Park?”; Firmite, “Gone with the wind?”

9 “Stu Miller,” Baseball-Reference.com, Corbett, “Stu Miller”; Firmite, “Gone with the wind?”

10 Corbett, “Stu Miller.”

11 “The Flying Nun”, FETV:real family entertainment, Accessed January 20, 2020, https://fetv.tv/show/the-flying-nun/.

12 “1961”, Franchise Timeline, MLB.com.

13 Firmite, “Gone with the wind?”

14 Bob Cairns, Pen Men: Stories Told by the Men Who Brought the Game Relief, New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1992, 249.

15 Cairns, Pen Men, 141. Thorn, The Relief Pitcher, 145.

16 James and Neyer, The Neyer/James Guide to Pitching: An Historical Comparison of Pitching, Pitchers, and Pitches, 310. Thorn, The Relief Pitcher, 146; Corbett, “Stu Miller.”

17 Boyd and Harris, The Great American Baseball Card Flipping, Trading, and Bubble Gum Book, 59.

18 The Neyer/James Guide to Pitching, 309-310; Cairns, Pen Men, 119; Tex Maule, Corbett, “Stu Miller”; Thorn, The Relief Pitcher, 146; “The Young Pitchers Take Command,” Sports Illustrated, June 26, 1961, Accessed January 14, 2020, https://www.si.com/vault/1961/06/26/581768/the-young-pitchers-take-command.

19 Tex Maule, “The Young Pitchers Take Command,”; Childs Walker and Mike Klingman, “Remembering 1966: The Orioles’ World Series that began with a remarkable run,” Baltimore Sun, April 1, 2016, Accessed July 2, 2019, https://www.baltimoresun.com/sports/orioles/bs-sp-orioles-1966-anniversary-20160402-story.html.

20 R.J. Lesch, “Moe Drabowsky”, SABR BioProject, Accessed November 24, 2019, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/51ef7eab; Roger Angell, The Summer Game (New York: Popular Library,1962-1972), 158.

21 Richard Goldstein, “Moe Drabowsky, Pitcher and Accomplished Prankster, Dies at 70”, The New York Times, June 13, 2006, Accessed January 10, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2006/06/13/sports/13drabowsky.html. Kiersh, Where Have You Gone Vince DiMaggio?, 19. Lesch, “Moe Drabowsky”; Bill Ordine, “O’s Series Hero was prankster, too,” Baltimore Sun, June 11, 2006, Accessed January 13, 2020, https://www.baltimoresun.com/sports/bal-sp.drabowsky11jun11-story.html. Walker and Klingman, “Remembering 1966: The Orioles’ World Series that began with a remarkable run.” Snake pranks included wearing them, mailing to ex-teammates, and hiding them in teammate’s lockers, personal items, and apparel, as well as in a bread basket at a banquet. Hotfoot pranks were played on players and coaches, Commissioner Bowie Kuhn, and sportswriter Hal Bock twice on the same road trip. Firecrackers turned up on benches, in restroom stalls, and once in the teepee of the Atlanta Braves mascot, Chief Noc-A-Homa. Prank calls included ordering takeout from a Hong Kong restaurant and impersonating rival manager Alvin Dark on a bullpen telephone and owner Charles O. Finley during a contract dispute. Before the first game of the 1969 World Series, an airplane flew over Baltimore’s Memorial Stadium towing a banner warning to beware of him, even though he was playing for neither team

22 Lesch, “Moe Drabowsky.”

23 Angell, The Summer Game, 156, 163; Corbett, “Stu Miller”; Lesch, “Moe Drabowsky.”

24 Jimmy Keenan, “April 30, 1967: Steve Barber and Stu Miller combine for no-hitter in a loss,” Accessed January 10, 2020, SABR Games Project, https://sabr.org/gamesproj/game/april-30-1967-steve-barber-and-stu-miller-combine-no-hitter-loss; Thorn, The Relief Pitcher, 147.

25 The first was Ken Johnson on April 23, 1964.

26 Martinez, in turn, was succeeded by Gregg Olson (217 career saves:1988–2001) with 160 saves for the 1988–93 Orioles, a team record that stood through the 2019 season. “Tippy Martinez,” Baseball-Reference, Accessed July 3, 2019, https://www.baseball-reference.com/players/m/martiti01.shtml; ”Baltimore Orioles Top 10 Career Pitching Leaders”, Baseball-Reference.

27 Wilhelm had no saves in 1959 when he was used primarily as a starting pitcher. “Hoyt Wilhelm,” Baseball-Reference.com.

28 Next tiers for pre-DH are primarily 1960s relievers with 100 or more career saves: Jack Aker (124 career saves 1964–74), Dick Radatz (120 career saves, 1962–69); then Ron Kline (108 career saves, 1952–70) and Wayne Granger (108 career saves, 1968–76). The DH rule may have contributed to the first reliever generation with 300 (or more) career saves, pitching mainly during the Seventies and into the Eighties, including the following: Hall of Famers Rollie Fingers (341 saves, 1968–85); Rich Gossage (310 career saves, 1972–94) and Bruce Sutter (300 saves, 1977–88).

29 Brooks, ”Did Stu Miller Really Get Blown Off the Mound at Candlestick Park?”