Swepsonville Ballpark: A Step Back in Time to North Carolina’s Textile Leagues

This article was written by Mark Cryan

This article was published in Spring 2022 Baseball Research Journal

As Major League Baseball cuts out the lower rungs of the minor-league ladder, author David Lamb’s observations on the nature of the minors become ever more poignant: “Although on the surface, the minors may seem like a quaint relic of America’s mom-and-pop era, the truth is that in the past decade, they’ve moved into the big time.”1 As minor league baseball is driven farther from its smalltown roots by economics and MLB fiat, it becomes even more important to remember the small communities from which baseball’s grassroots grew—places like Swepsonville, North Carolina.

INDUSTRIAL LEAGUE BASEBALL

More than sixty cities and towns in North Carolina have fielded professional minor league teams at some point in their history. There are also towns like Asheboro, Roxboro, and Swepsonville that have never hosted professional ball, but nonetheless boast a long and proud baseball history.2 The cities listed above, and many others, hosted textile league or mill teams. While this was not technically considered “professional” minor league baseball, there were definitely players being paid to play for these teams and large numbers of people paid admission to see games. In fact, the competition may have been more fierce, due to the fact that these teams existed only to win games, and not for the purpose of developing players to be sold to higher level leagues.3,4 During the Great Depression, for example, players in the Northwest Georgia Textile League might make $12 to $17 per week for working in the mill, but would be paid an additional $4 to $7 to play baseball.5 Likewise, it was also well-known that for some mill team players in North Carolina’s Piedmont region, “their real job was playing baseball.”6

It’s also worth noting that minor league baseball in North Carolina was rigidly segregated from its beginnings. Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier when he joined the Brooklyn Dodgers’ top minor league team in Montreal in 1946, but the first black player didn’t appear in a professional game in North Carolina until 1951, when Percy Miller Jr. was signed by the Danville (VA) Leafs, and played games in North Carolina.7 The textile leagues of the 1940s and 1950s, like virtually all aspects of life in the South during this time period, were likewise segregated by race, and the opportunity to play for the mill team was available only to white male employees.8,9

Piedmont area mills also recruited players from outside the area, and engaged in hiring practices that prioritized baseball success over talent at working the mills. The better local ballplayers could also often negotiate a better position with another mill, creating a level of agency and power that was not available to most textile workers.10 The level of play in many of these textile leagues rivalled that in many minor leagues.11 Consider the “outlaw” Carolina League of 1936-38. Textile league baseball was so competitive in the area around Kannapolis and Concord that the team operators declared themselves a professional league, but one without the sanctioning of the National Association, the governing body of minor league baseball. In this period, the Carolina League was competing with official National Association leagues for talent, and at one point, the head of minor league baseball, Judge Bramham, offered the Carolina League sanctioned status if they would come into the fold.12

There were also leagues that had roots in textile baseball like the Bi-State League, with teams in North Carolina and Virginia. That loop was accepted into “organized baseball” in 1934 and competed until 1942.13,14 The line between textile league baseball and minor league baseball was blurry at best.

SWEPSONVILLE AND ALAMANCE COUNTY TEXTILE INDUSTRY

For generations, Alamance County was defined by the textile industry that grew up along the banks of the Haw River. The first mill was established in 1832 by John Trollinger.15 Within a few years, E.M. Holt had opened the first mill for what would become one of the area’s most important textile companies.16 These mills were often in locations that originally housed the grist mills built by early settlers, some as early as 1745. The ready availability of water power from the Haw helped the industry grow in the region. Eventually, Alamance County became something of a brand in the textile industry, as dyed yarns became popular and the resulting distinctive patterns became known as the “Alamance Plaid.”17

Among the early mills was a production facility south of Graham, North Carolina, in a settlement that derived its name from the original owner of the mill, George William Swepson. Despite the location on the banks of the Haw, the mill was originally known as the Falls Neuse Mills, owing to Swepson’s prior ownership of a paper mill located alongside the Neuse River near Raleigh.

The Falls Neuse Mill was producing the distinctive Alamance Plaid in 1870. By 1883, though, Swepson was dead, amid rumors he may have committed murder and arson before his death. The mill was taken over by Ashby L. Baker, who was married to Swepson’s niece, Virginia McAden. Baker renamed the mill in her honor shortly after her death in 1893.18 The Virginia Cotton Mill continued to be the centerpiece of life in Swepsonville for decades. It thrived during World War I, but the Great Depression took its toll, leading to bankruptcy and reorganization in 1933.19 The Depression affected all areas of the economy, and baseball was not immune. There were 26 professional minor leagues across the country in 1929, but by end of the 1933 season, only 14 were still operating.20

Mill teams in Piedmont communities like Swepsonville, though, were able to continue playing ball. In fact, like many area mills, the leadership of Virginia Mills looked to provide their workers more recreation as a distraction from both a struggling economy and nascent unionization efforts that were taking hold in North Carolina. “Big companies of every kind promoted baseball for their workers. Management believed it promoted teamwork, provided a healthy way to fill spare time that might otherwise be devoted to labor agitation and taught immigrant workers how to be ‘real Americans.’”21

Virginia Mills built a ballfield just down the road from the mill, at the end of West Main Street, in 1926.22 This was happening as Alamance County saw growing unrest between labor and management. Some of these tensions dated back to the turn of the century, moving into a critical period following the “stretch-out” of the 1920s, when mill workers were faced with increasing automation and higher production quotas.23 This unrest included the declaration of a general strike by the United Textile Workers in 1934, and the arrival of union activist “Flying Squadrons,” causing some mill owners to call on the National Guard to protect their mills.24

Against this backdrop, many mill owners across the South offered various enticements to reduce the attraction to unions. These included free housing and diversions like mill baseball teams.25,26 Union organizers were not able to make much progress in the mill villages. Life in North Carolina continued with little change, as workers lived in housing provided by the mill and shopped at the company store. Their children attended schools provided by the mills, and their recreation and social opportunities were largely provided by the mill.27 There are newspaper accounts of Swepsonville teams competing in a circuit called the Central Carolina League as far back as 1934, playing against teams from Glencoe, Burlington, and Graham.28 Accounts from 1935 show Central Carolina League standings including teams from Graham, “Greensboro (Prox)” (denoting Proximity Manufacturing, the predecessor of textile giant Cone Mills), Swepsonville, and Burlington.29

As the 1930s turned into the 1940s, World War II created tremendous demand for textiles, and brought prosperity and growth to many local manufacturers, including Virginia Mills. In fact, Swepsonville’s Virginia Mills added 90,000 square feet of additional space between 1934 and the end of the war.30 In 1943, the mill’s owner created the Baker Foundation, which was established for the promotion of social and recreational activities in the village.31 The foundation’s works included building a community center, a playground, adult softball leagues, and a junior baseball program. The foundation also constructed a covered grandstand and installed lights on what had been just a ballfield since play began there in 1926.32

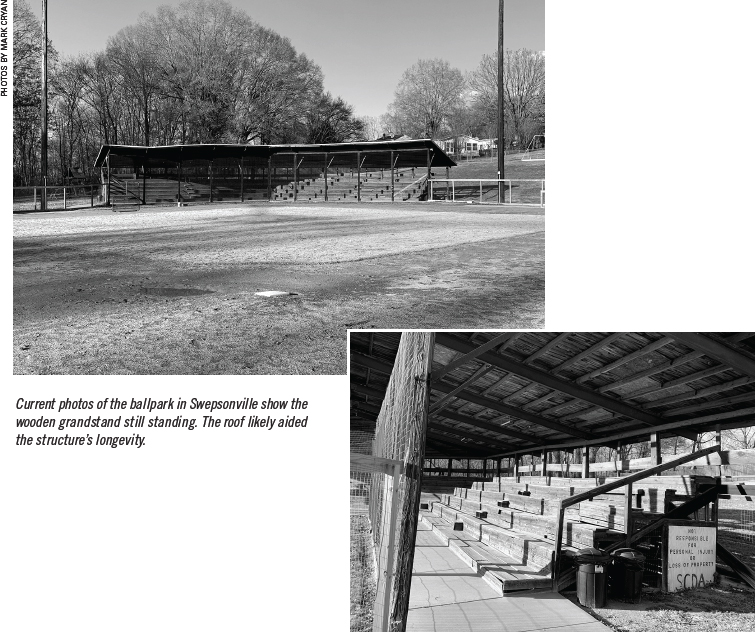

Remarkably, this grandstand is still in place today. Aside from repairs and maintenance work, this is essentially the same ballpark where mill workers sat to cheer on their coworkers over seventy years ago. It’s a simple wood grandstand, built of boards, poles, and planks, with just five rows of simple bench seats beginning at ground level, and a total capacity of roughly two hundred people. Unlike the typical design, made up of one section of seats directly behind home plate, and two flanking sections angled down the lines, this grandstand is composed of just two sections that meet directly behind home plate. The resulting shape is like a very shallow “V.” The secret to its survival is likely the size of the roof, which completely overhangs the entire seating areas and has protected the structure from the damaging elements for many decades. For a small-town mill team in the 1940s, it was a state-of-the art facility.

The grandstand project included lighting, ushering in night baseball. The park also was surrounded by a board fence designed to prevent people from watching the mill team’s games without paying.

The teams that played in Swepsonville and the Central Carolina League may not have been as strong as the best industrial teams, like the Bi-State League that moved up to Class D status in 1934, or the aforementioned Carolina League, which fielded teams studded with former minor-and major-league players.33 Despite that, there was a healthy competitive scene in the central part of North Carolina, not only with teams from Alamance County playing one another in the Central Carolina League, but also a yearly tournament that was billed as a “Semi-pro State Championship” for these teams and others, held in Roxboro.34,35 Like many of the industrial leagues, this team operated in territory that eventually included minor league professional teams. The Central Carolina League, which was an organized entity by the 1930s, centered around the Burlington area, which also fielded teams in the Bi-State and Carolina Leagues in 1942, 1945-55, and 1958-72.36 By the 1950s, Swepsonville and other mill towns were still sponsoring semi-pro teams, but many were also fielding community youth teams filled with sons of the mill employees.37

THE ROAD TO THE SHOW

Most area textile teams were made up of some talented local players who happened to work at the mill, as well as a handful of players who were recruited to work at the mill specifically to play baseball. But some years, these teams would include players who were on their way to the big leagues, like Tal Abernathy of the 1940 Burlington Mills team that won the state semipro championship.38 The Alamance County area had produced notable ballplayers decades before, including Tom Zachary, a successful major league pitcher from 1918 to 1940, who unfortunately became best known for surrendering Babe Ruth’s record-setting 60th home run.39 The Swepsonville community and the surrounding areas produced their share of talent as well. Dusty Cooke was born in Swepsonville in 1907, and made his major league debut with the New York Yankees in 1930. He was a lefthanded-hitting outfielder who played in 608 big league games before returning to the minor leagues after the 1938 season.40 Don Thompson went from the Swepsonville ballpark to the majors. He spent four years in the big leagues, including the 1953 season with the Brooklyn Dodgers. He played 96 games that year, sharing left field with Jackie Robinson, who split time between the outfield and second base. The Dodgers won the National League pennant that year before falling to the Yankees in the World Series.41,42 Floyd Wicker from nearby Burlington was another Alamance County product who played at the Swepsonville Ballpark on his way to the big leagues. He played 81 games for Montreal, Milwaukee, St. Louis, and San Francisco between 1968 and 1971. He originally signed with the Cardinals after playing a single season for East Carolina University (then College), helping the Pirates to the NAIA World Series championship.43 Among the most well-known hometown teams was a group of 12-13-year-old youths from Swepsonville known as the “Overall Boys,” who won a state championship in 1947. This team, playing in overalls while competing against teams from larger, more affluent communities in full uniforms, became a crowd favorite during the tournament.44,45

A player who was recruited to play ball for the mill, Bob Vaughn became such a favorite son of Swepsonville that one of the roads leading to the ballpark was named for him. He also recorded an early version of the “Splash Home Run” that Barry Bonds made famous in San Francisco. Playing for the Swepsonville mill in the 1950s, he hit a mammoth home run down the right field line, which carried beyond the outfield fence and another fifty feet, landing in the neighboring Haw River.46

LIFE BEYOND THE MILL; YOUTH BASEBALL, HIGH SCHOOL AND SUMMER COLLEGE BALL

World War II was an era of great prosperity and growth. But, like many of the mills in the area, Virginia Mills saw decline in the postwar period, as textile production migrated out of North Carolina in search of lower wages. Virginia Mills was closed in 1970. In 1989, the mill complex was destroyed by what is said to be the largest structure fire in the history of North Carolina.47

This was also an era of increasing competition for locally-oriented entertainment like mill team baseball. Television was growing in popularity and air conditioning was beginning to appear in homes.48 Posing even more immediate competition just up the road, the city of Burlington opened a new concrete and steel ballpark in 1960 with a capacity of several thousand fans to house their MLB-affiliated minor league team, the Alamance Indians of the Carolina League.49

The site of Virginia Mills is now a large open field dotted with brick and concrete foundations. One can only imagine the noise and activity level while the mill complex was still operating, as it cranked out textiles for the U.S. efforts in both world wars. As late as 1969, the mill was still running three shifts, with roughly 1200 people employed. The death of Walter M. Williams, who led the mill and had strong ties to the garment industry in New York City, was identified by many in the community as a death blow to the mill as well, as it closed shortly thereafter.50

Although the mill is no more, the ballpark lives on, and currently hosts baseball at a variety of levels. Of course, even when the mill was in its heyday, the field was used for more than textile league games. Youth baseball and adult softball sponsored first by the mill, later by the Alamance County Recreation Department, has continued to be played there.

Nearby Southern Alamance High School used the field for baseball and softball games prior to construction of fields on their campus. One of those Southern Alamance High School players was Raymond Herring, who played outfield for Southern when they won a state championship in 1965.

It was during his high school years that Herring met a girl from Swepsonville who became his wife, and the couple moved there after they were married. While running a successful construction company, Herring spearheaded Swepsonville’s efforts to become an incorporated town, and then served as mayor for 22 years, from 1997 to 2019.51

During that time, he led the way on a number of projects. One was the Swepsonville River Park, a part of the Haw River Hiking and Paddle Trail that sits on the opposite bank of the Haw River, within sight of the ballpark. But the ballpark was always especially close to Herring’s heart, and even before he took over as mayor, preservation of this gem was a priority for him and other concerned citizens of Swepsonville.

Shortly before the mill closed down, the Swepsonville Community Development Association, a group of civic-minded local residents, took over the ballpark, community center, and playground from the Baker Foundation. A lease was signed in 1967, giving all the community’s facilities over to the association for $3 a year.52

Over the years, the association undertook renovations, including a major round of work in the early 1990s. The group built a picnic area, walkways, handicapped accessible bathrooms, and a modern concession stand. Herring was hands-on with much of this work, including pouring “every bit of the concrete” in the ballpark.53

The association also oversaw a replacement of the lighting system in the late 1980s, funded by a distribution of money resulting from the closing of the Graham Savings Bank. While the association kept the facility in operation and were able to undertake some repairs, the town took over management and ownership of the ballpark in the late 1990s.54

Recently, the Old North State League, a summer college baseball league based in North Carolina, approached the town about using the Swepsonville Ballpark as the home field for a team. The Swepsonville Sweepers took the field with a roster consisting mostly of players from North Carolina, representing schools like Greensboro College, Guilford Tech, North Carolina Central University, Fayetteville Tech, and Catawba.55

The Old North State League also sponsors a showcase league for high-school-age players. The league also played Old North State League tournament games in Swepsonville, making this ballpark a very busy place.56 In exchange for the use of the field for the college team and the showcase ball, the Old North State League improved and repaired fencing, and invested in improving the playing surfaces.

This was a tremendous benefit to a small municipality like Swepsonville, which has no property tax and relies on their pro-rated share of the county’s sales tax for all its funding, according to Town Administrator Brad Bullis. He grew up in the area and remembers playing youth baseball in the Alamance County Recreation Department’s recreation leagues at the Swepsonville Ballpark. Bullis was pleased with both the improvements, and the visitors it brought to Swepsonville and the county.57

“A REAL GEM”

This ballpark is hidden away in a modest residential neighborhood just a few blocks from the traffic light at Swepsonville’s main crossroads, Main Street and Swepsonville-Saxapahaw Road. Nestled between the Haw River and a large pond, with only trees and the river beyond the outfield wall, this ballpark is a true step back in time. With the pop of the glove and the sound of the ball hitting the bat, attending a game here can give visitors a glimpse into the history of the game, and perhaps, an ever-rarer glimpse into its heart.

MARK CRYAN is an assistant professor of sport management at Elon University. He previously served as the general manager of the Burlington (NC) Indians in the Appalachian League, helped found the Coastal Plain League, and was athletic director for the Burlington (NC) Recreation & Parks Department. He is the author of Cradle of the Game: Baseball and Ballparks in North Carolina.

Author’s Note

This research project was greatly aided by Mayor Robert Herring, a former local ballplayer and fan who has been termed the “George Washington” of Swepsonville, as well as Burlington Recreation Director Tony Laws, and Swepsonville Town Administrator Brad Bullis.

Further Reading

Anyone who is interested in learning more about textile league baseball and the early history of minor league baseball in North Carolina should pick up Hank Utley and Scott Verner’s meticulously researched and eminently readable book, The Independent Carolina League, 1936-1938: Baseball Outlaws.

Few counties have such a thorough and well-written history available as Shuttle & Plow: A History of Alamance County by Carol Troxler and William Vincent.

The Minor League Baseball Encyclopedia by Miles Wolff and Lloyd Johnson, even in the Internet age, remains an invaluable resource, just as it was when I was scouting cities for the Coastal Plain League.

Notes

1. Geoffrey C. Ward and Ken Burns, Baseball: An Illustrated History (New York: Knopf, 1994), 146.

2. Mark Cryan, Cradle of the Game: Baseball and Ballparks in North Carolina, 2nd Ed. (Middleton, Wis.; August Publications, 2014)

3. R.G. (Hank) Utley, Scott Verner, The Independent Carolina League, 1936-1938: Baseball Outlaws (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 1999) and Chris Holaday, Professional Baseball in North Carolina; An Illustrated City-by-CityHistory, 1901-1996 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 1998), 200.

4. Chris Holaday, Professional Baseball in North Carolina; An Illustrated City-by-City History, 1901-1996 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 1998) 200.

5. Heather S. Shores, “Working to Play, Playing to Work: The Northwest Georgia Textile League,” The National Pastime: Baseball in the Peach State, #30, 2010, 18-30.

6. Raymond Herring (former Swepsonville mayor) in discussion with the author, December 15, 2020.

7. Holaday, 197.

8. Shores, 18-30 and Mary Frederickson, “Four Decades of Change: Black Workers in Southern Textiles, 1941-1981,” Radical AmericaVol. 16 #6, 1982, 27-43.

9. Shores, “Working to Play,” 18-30.

10. Don Bolden, 20th Century Alamance: A Pictorial History (Burlington, NC: Times-News Publishing, 2002), 56.

11. Holaday, 200.

12. Utley and Verner, 138.

13. Utley and Verner, 225 and Lloyd Johnson and Miles Wolff, eds., The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, 2nd ed. (Durham, NC: Baseball America, 1997), 45.

14. Utley and Verner, Baseball Outlaws, 225.

15. Carol W. Troxler and William M. Murray, Shuttle & Plow: A History of Alamance County, North Carolina (Burlington, NC: Alamance County Historical Association, 1999), 344.

16. Bolden, 56.

17. Troxler and Murray, 349.

18. Troxler and Murray, 359.

19. Troxler and Murray, 345.

20. Johnson and Wolff, 263

21. Ward and Burns, 124.

22. Jessica Williams, “Swepsonville’s Founding Father Retires,” Burlington Tmes-News, March 25, 2019, accessed February 22, 2022. https://www.thetimesnews.com/story/news/politics/county/2019/03/25/swepsonvillesfirst-and-only-mayor-to-retire-after-22-years/5628093007.

23. Troxler and Murray, 373

24. Troxler and Murray, 373.

25. Shores, 18-30 and Troxler and Murray, 371.

26. Troxler and Murray, Shuttle & Plow, 371.

27. Herring interview.

28. “Graham to Meet Sweps in Headliner at Sweps,” Burlington Daily Times-News, August 3, 1934, 3.

29. “Central Carolina League; Graham Blanks Sweps,” Burlington Daily Times-News, May 24, 1935, 3.

30. Troxler and Murray, 359.

31. Troxler and Murray, 359.

32. “Baker Foundation Finishes Summer Activity Programs at Swepsonville,” Burlington Daily Times-News, September 22, 1948, 11.

33. Utley and Verner.

34. Tony Laws (Burlington Recreation and Parks Director) in conversation with author December 2020 and ’’Swepsonville in Action Against Oak Ridge Nine,” Burlington Daily Times-News, July 26, 1951, 6.

35. “Swepsonville in Action Against Oak Ridge Nine,” Burlington Daily Times-News, July 26, 1951, 6.

36. Johnson and Wolff, 45.

37. Bolden, 75.

38. Bolden, 56.

39. “Tom Zachary,” Baseball Reference, accessed February 22, 2022. https://www.baseball-reference.com/players/z/zachato01.shtml.

40. Bill Nowlin, “Dusty Cooke,” SABR Biography Project, accessed February 22, 2022. https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/dusty-cooke.

41. Herring interview and “Don Thompson,” Baseball Reference, accessed February 22, 2022. https://www.baseball-reference.com/players/t/thompdo01.shtml.

42. Herring interview.

43. “Floyd Wicker,” Baseball Reference, accessed February 22, 2022. https://www.baseball-reference.com/players/w/wickefl01.shtml

44. Herring interview and ”Swepsonville Juniors Win State Crown,” Burlington Daily Times-News, August 21, 1947, 15.

45. Herring interview.

46. Herring interview.

47. Troxler and Murray, 359.

48. Johnson and Wolff, 411.

49. Cryan, 28-31.

50. Herring interview.

51. Williams.

52. Connor Jones, “Swepsonville Gets Recreation Units from Baker Foundation,” Burlington Daily Times-News, March 15, 1967, 36.

53. Herring interview.

54. Brad Bullis (Swepsonville town administrator) in conversation with the author, December 2020.

55. “Swepsonville Sweepers,” The Official Home of the Old North State League, accessed February 22, 2022. https://oldnorthstateleague.com/members/swepsonville/Swepsonville_Sweepers.

56. “Schedule,” The Official Home of the Old North State League, accessed February 22, 2022. https://oldnorthstateleague.com/schedule-all.

57. Bullis interview.