Tales from Interviewing the Whiz Kids

This article was written by C. Paul Rogers III

This article was published in 1950 Philadelphia Phillies essays

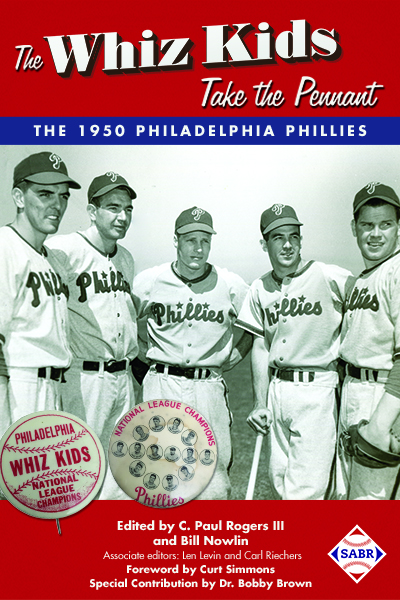

When I approached Robin Roberts in 1992 about writing a book on the famous Whiz Kids team that won the 1950 pennant on the last day of the season, he was immediately all in. Since I’d never written a baseball book (although heaven knows I’d read enough of them), I felt a little like the dog who chases a car and catches it. What do I do now? Since Robin had been my boyhood hero and now I had the chance to write a book with him, I particularly felt the pressure.

When I approached Robin Roberts in 1992 about writing a book on the famous Whiz Kids team that won the 1950 pennant on the last day of the season, he was immediately all in. Since I’d never written a baseball book (although heaven knows I’d read enough of them), I felt a little like the dog who chases a car and catches it. What do I do now? Since Robin had been my boyhood hero and now I had the chance to write a book with him, I particularly felt the pressure.

My thought was to work intensively with Robin about his memories of that epic season, but also to interview as many of the living Whiz Kids as possible. Robin liked that idea a lot since to him that team represented an ultimate team accomplishment and he didn’t want the book to be just about himself. In addition, he was curious about how his teammates viewed that 1950 season with 40-some years of hindsight. One thing Robin and I quickly learned along those lines was how people involved in the same event can perceive it very differently. Not only do their memories differ of, for example, key games, but also do their perceptions of those games.

I set about interviewing as many Whiz Kids in person as I could over the next three or so years and ended up with some very memorable experiences. I was determined to conduct the interviews in person when possible, both because I thought face-to-face would produce much better results and because I really wanted to meet these guys. I started by flying up to meet Robin in the Philadelphia airport and driving with him to Valley Forge to visit with the then 87-year-old manager of the Whiz Kids, Eddie Sawyer. Eddie was known for his photographic memory, and pretty much all I did was listen as the two of them, who obviously had great affection for each other, reminisced while my tape recorder ran. I really didn’t know what I was doing, but had a wonderful afternoon soaking it all in.

Robin was to throw out the first pitch that evening in Wilmington, Delaware, which was resurrecting professional baseball for the first time in about 40 years. Since Robin had starred with Wilmington in 1948 just prior to being called up to the Phillies, he was a natural to help inaugurate the new era of Blue Rocks baseball. But Eddie and he talked so long that he lost track of the time (I was clueless as to when we needed to leave) and suddenly realized that we needed to leave post haste to get to Wilmington in time for the game. The problem was that it was pouring down rain and we got lost trying to get off Valley Forge Mountain. It’s quite a hike from Valley Forge to Wilmington and we simply weren’t going to make it by the time we finally got off that mountain. The only thing that saved Robin was that it was raining in Wilmington as well and the game was postponed until the next afternoon.

The logistics of arranging in person-interviews can be a challenge, but it is a rewarding experience when the schedule goes as planned and you have some good interviews. On a memorable day that went like clockwork I was able to interview three former players in three different locations all around the Philadelphia metropolitan area. I was staying in midtown Manhattan attending a conference, which got me to the east coast. I played hooky from my meetings one day as planned, rented a car in midtown, rose at 5 A.M, drove to the Limekiln Golf Club in Ambler, Pennsylvania to interview Curt Simmons at 8 A.M. (Simmons and Roberts were co-owners of the course). After interviewing Curt with lawnmowers in the background, I met Del Ennis at 11 at his house in Huntington Valley, also north of Philadelphia.

My next stop was midafternoon at Veterans Stadium in south Philly where I’d arranged to talk to Maje McDonnell, who still worked for the Phillies in community relations. After a wonderful interview with Maje, I headed back to New York, arriving back in midtown late evening. It was an exhilarating, almost surreal day, and as I look back, I’m amazed that I, a Dallasite from far away Texas, managed it all without the aid of a GPS, cellphone, or even email.

I very much wanted to interview Dick Sisler, who had hit the most dramatic home run in Phillies’ history, a 10th-inning clout on the last day of the season against the Dodgers in Brooklyn to win the pennant. He lived in Nashville, but I learned from his wife Dot that he was in a nursing home, suffering from dementia. But she thought that he had enough long-term memory to be of help, so I arranged to drive over from Dallas in the summer of 1993.

It was a very sad experience. Dick’s room in the nursing home was stark, with a bed, a chest of drawers, and a couple of chairs. There were a couple of family photos on the walls and the dresser, but no hint of his baseball career. Dick was 73 years old and looked like he could still play. He was relatively trim, erect, and still stood about 6’2” tall. He was one of the few men in the facility and, from his robust physical appearance, looked like he was in the wrong place. I had prepared thoroughly for the interview and with some prodding Dick was able to recall some events from his playing career, such as when he played winter ball in Cuba and became known as the Babe Ruth of Cuba because of several tape-measure homers he hit down there. He also hadn’t forgotten his momentous home run to win the 1950 pennant.

But as anyone who has dealt with dementia knows, Dick’s memory was selective. He did not seem to have much recollection, for example, of his Hall of Fame father, George Sisler.

I later had a similar experience with Bill Nicholson, who had been one of the veterans on the team in 1950 at 34 and was also one of most admired. Bill had written me that he just didn’t have any memory of his baseball career and that he was sorry but he didn’t think he could help me. I was later able to meet him briefly when I flew back to a card show in suburban Philadelphia where several Whiz Kids, including Nicholson, were to sign autographs. Nicholson, who was the top slugger in the National League during the war years, was called “Swish” because of the noise his hard swing made when he failed to connect. At the show, Bill knew his nickname, but only because it had been drilled into him recently. When Richie Ashburn arrived at the show, he knelt down and told Bill who he was and that they’d been teammates on the Phillies. Bill pretended to know Richie, but couldn’t engage in much conversation, and after a few minutes Ashburn got up with tears in his eyes.

On the same trip that I met with Dick Sisler, I next drove down to Birmingham to interview Bubba Church, a rookie pitcher in 1950 who had won several crucial games for the club before being felled by a line drive off the bat of Ted Kluszewski during the stretch run. The visit was one of the highlights of my time with the Whiz Kids. Bubba, who exuded genuine Southern charm, and his wife Peggy couldn’t have been more accommodating or helpful. While I interviewed Bubba, Peggy chatted with my 15-year old-daughter Jillian, who had been visiting a friend in Tennessee and was now with me. The Whiz Kids were so important to Bubba that he choked up more than once recalling that time in his life.

Bubba had arranged for me to interview Ben Chapman, who had managed the Phillies into 1948 when the Whiz Kids were starting to arrive in the big leagues, but unfortunately Chapman had passed away about 10 days before my visit. He had also arranged an interview with Harry “the Hat” Walker, who lived in Leeds, a Birmingham suburb. Walker had won the 1947 batting title as a Phillie and had a great perspective on the organization during that time. It was a long hike to Leeds from the Churches and so they led us there in their car. Then, while I interviewed Walker (or rather listened to him since he talked non-stop for about an hour) and got to hold his famous two-toned bat from the 1946 World Series, the Churches took Jillian off to a late lunch.

They returned Jillian to me and decided that I needed to get something to eat, so insisted on leading us to a restaurant on our way out of town and sat and watched me eat. Bubba and Peggy became fast friends and when he was inducted into the Alabama Sports Hall of Fame in 2001, I was there along with his Whiz Kids teammates Robin Roberts and Andy Seminick.

Perhaps my most memorable experience involved an interview no-show. Pretty early in this process, a Philadelphia entrepreneur put together a huge memorabilia and autograph show in the Philadelphia Convention Center featuring the Whiz Kids and the Phillies 1980 World Championship team. It was an opportunity too great to miss, so I flew up with the goal of interviewing as many Whiz Kids as I could. I particularly wanted to interview Granny Hamner, the Whiz Kids shortstop, who hadn’t responded to me.

On Saturday night during the show, the promoter hosted a reception and dinner for the ballplayers, and Robin made sure I was included. Bubba introduced me to Hamner at the reception and told him what I was doing and that he really should agree to talk to me. Granny agreed to let me interview him and told me to come to his hotel the next morning around 10:00.

The next morning I interviewed Putsy Caballero at 9 A.M. and then headed over to Granny’s hotel in a cab. The promoter had obtained comp rooms for the players at hotels all around Philadelphia’s Center City, and Granny’s hotel was on the other side of downtown. I got there a couple of minutes after 10 and immediately called Hamner’s room. No answer. He’d said to look in the coffee shop if he wasn’t in his room, but he wasn’t there either. I continued to call his room and check the coffee shop for about 30 minutes or so. Robin had told me that Granny wasn’t exactly known for his reliability, so I wasn’t entirely surprised, although was I of course disappointed.

By some small miracle, I remembered Granny’s room number, so I finally decided to go knock on his door. When I did, I could hear either the radio or TV on at low volume inside the room, but there was still no answer. Of course, that doesn’t mean someone is in the room, only that someone has been there. Granny was supposed to sign autographs at one that afternoon, so I went over to the show, hoping that perhaps I could sit with him and ask him a few questions while he signed. There was a fairly long line of people waiting to get his autograph at the appointed time, but he didn’t show up.

Robin thought that Granny had probably gone off on a bender and would surface in a couple of days. I flew home to Dallas that evening having met Granny (and taken his picture with some of his teammates) but without an interview. I was in my office the next day, Monday, when Robin called about 8:30. He said, “I found out why Granny didn’t show up for the interview with you yesterday. They found him dead in his hotel room.”

Apparently, shortly after I knocked on his door, housekeeping tried to get in the room and couldn’t and called hotel security. They found him not breathing in the chair in his room, apparently waiting for me.

To add to this sad story, I distinctly remember Granny telling Robin, Bubba, and Putsy the night before that he’d just had a checkup and that his doctor had told him he was as healthy as a horse, but that he really should stop smoking.

Most of the former players that I interviewed were very nostalgic about their baseball careers and were happy to reminisce. But for some, it seemed to evoke difficult memories. For example, my attempts to interview Mike Goliat, the second baseman of the Whiz Kids, proved unavailing. Although Goliat was a key contributor to the team, 1950 proved to be his only full season in the major leagues, making him the answer to an oft-asked trivia question, “Who was the second baseman for the Whiz Kids?” Goliat reported to spring training in 1951 overweight and out-of-shape, was shortly sold to the St. Louis Browns, and after a handful of games there was back in the minor leagues, never to return to the Show. When I called to arrange a meeting, I could never get past his wife Eleanor and pretty soon it became evident that Mike just didn’t want to talk to me.

Another example was Ken Johnson, a left-handed pitcher, who as a spot starter had won four games against a single loss for the Whiz Kids, including a couple of complete-game shutouts. But Johnson’s career had also been a disappointment, mostly due to a lack of control. Ken lived in Wichita, Kansas and had a very successful post-baseball career as an insurance executive. I was anxious to interview him because he seemed almost reclusive about his baseball career, even though he’d been a real contributor in 1950. He wasn’t in touch with any of his teammates and was the only Whiz Kid who hadn’t attended the team’s 25-year reunion in Philadelphia in 1975.

Ken and his wife couldn’t have been nicer when I traveled to Wichita, taking me to dinner at the Wichita Country Club, where Ken seemed to know everyone and was clearly a pillar of the community. But interviewing him about his baseball career proved painful to him, because he thought he had squandered his talent. He viewed it as the most unsuccessful period of his life and best forgotten. I tried to convince him otherwise, but don’t think I was particularly successful.

I had a somewhat similar experience when I reached Paul Stuffel by phone. Stuffel had been a late season call-up as a 23-year-old rookie pitcher and appeared in three games with a 1.80 earned run average. But, also because of wildness, he had a very abbreviated major-league career. When I told him about the Whiz Kids project, he said, “Boy, you’re scrapping the bottom of the barrel talking to me.”

Even more poignant was my telephone conversation with Charlie Bicknell, whom the Phillies had signed for a sizeable bonus right of high school. Because of the bonus baby rule then in effect, the Phillies were forced to keep Bicknell on the major-league roster for two years, which in his case were the 1948 and 1949 seasons. He’d pitched in only a handful of games those two years, mostly in mop-up duty, before being sold to the Boston Braves during spring training in 1950. Charlie told me how in 1948 when the team arrived in Philadelphia after spring training, everyone had two home and two road uniforms hung in their lockers. Bicknell, however, only had one of each.

Charlie told me, “I never said anything or told anybody, but that hurt. If you ever notice the 1948 team photo, you’ll see that I’m not in that picture. I’m not in it because I didn’t want to be. I told the team I had somebody sick back home on picture day.”

On the other hand, some bit players, such as utility infielder Putsy Caballero and Maje McDonnell, batting practice pitcher and unofficial coach, had much better experiences and viewed their Whiz Kid experience as the best of their lives, except for marriage and children. McDonnell told me that he knelt in the tunnel after the Phillies won the pennant in Ebbets Field and thanked God for the greatest moment in his life.

I also learned that one could undercover wonderful pearls by interviewing those who were close to the team. I interviewed by phone two sisters, Anne and Betty Zeiser, who were fervent, rabid Phillies fans and had formed the Andy Seminick Fan Club in admiration of the Phillies catcher. They had traveled to Brooklyn for the season’s final two games and, when the Dodgers won the first, Anne was caught on camera hitting a priest in the box seats in front of her over the head with a scorecard because he had rooted for the Dodgers. Anne was convinced that the priest had prayed the Dodgers into the win.

That night, before the final game of the season, the sisters went into a little church around the corner from their hotel to pray for a Phillies victory. There they saw infielder Putsy Caballero on his knees, praying and crying like a baby.

I was also able to interview Andy Skinner, the private pitching coach of ace reliever Jim Konstanty. Andy was an undertaker from Konstanty’s hometown in upstate New York who had no real baseball background. Skinner was a good bowler, however, and applied the techniques he used to spin a bowling ball to Konstanty’s slider and palm ball. Whenever Konstanty began to struggle, he’d call Skinner, who would drive to meet the team wherever it was playing. It must have worked; Konstanty won 16 games for the Whiz Kids in relief and was named National League Most Valuable Player.

Skinner related one occasion in which he’d driven a hearse to New York to meet Konstanty (and pick up a body) and had given a ride back to the team hotel from the Polo Grounds to Konstanty and several teammates, who’d had sit in back where the caskets ride. They caused quite a stir when the hearse pulled up to the hotel and three strapping ballplayers got out of the back.

When Jim Konstanty died too soon at age 59 in 1976, Andy Skinner was the undertaker.

In a couple of cases, the widows of former Whiz Kids proved very helpful. Mary Anne Hollmig, the beautiful widow of Stan Hollmig, visited with me by phone and sent me some great material on Stan. Through Wilma Brittin, I learned the remarkable story of her husband Jack, who, as a late season call-up, had pitched in three games for the Whiz Kids. Brittin had been a top prospect, but his career was derailed by puzzling but chronic arm and leg problems until he was eventually diagnosed as suffering from multiple sclerosis. He spent much of his life in a wheelchair, although he was able to have a successful career as a state education administrator in his native Illinois. Jack became reacquainted with former high school classmate Wilma after a gap of 23 years and they soon married and lived happily together for over 30 years, until Jack’s death in 1994.

The different personalities of old ballplayers are often striking to oral historians. I mentioned how Harry Walker talked non-stop and that I, as interviewer, could scarcely get a word in edgewise. In contrast, Del Ennis was a man of few words. He was the leading practical joker on the team, so I was surprised at how quiet he was. When I arrived at the appointed time at Del’s suburban Philadelphia home, he greeted me curtly at the door and bade me come in. Del ushered me down to his basement, which his second wife Liz had converted into a virtual shrine to his playing career, including his locker from old Connie Mack Stadium (In contrast, Dick Whitman’s Arizona home contained little or no hint he’d been a major-league ballplayer). Usually an interviewer can get into a flow of conversation with his subject, but it was tough with Del, because he answered my questions very succinctly and almost abruptly.

He was a kind man with a sparkle in his eyes, but he just wasn’t prone to much conversation. But I still managed to get some great material from him. For example, I asked him about the Gil Hodges’ fly ball he’d caught in the bottom of the ninth in the last game of the season with two outs and runners on second and third to send the game into extra innings. Contemporary accounts had described the ball as a routine fly to fairly deep right field.

“Easy fly ball all right.” Del said, “I lost the ball in the sun; the line drive hit me right in the chest and dropped right in my glove. I knew it was coming right at me so I just stood there and it hit me right in the chest. After the game, I had the seams of the ball in my chest.”

If Del had not caught that ball, the winning run would have scored, forcing a best-of-three playoff for the pennant.

Whew!

In addition to experiencing dramatically different personalities, an oral historian also quickly learns that some ballplayers have much better memories than others. For example, I was lucky because Robin Roberts, my primary subject for the Whiz Kids project, had an incredible memory for detail, enhanced by the fact that although he pitched for 18 years in the big leagues, he viewed the 1950 season as the highlight of his career. In contrast, for Curt Simmons, a 17-game-winner that year before his National Guard unit was called to active duty in August, the season was something of a blur. During our interview Curt would frequently tell me, ask Robin about that, he remembers everything.

Of course oral historians quickly learn that memories are inherently inaccurate and that events need to be verified. I’ve learned that the hard way more than once. For example, I talked to several Phillies about the infamous 1949 shooting of first-baseman Eddie Waitkus in a Chicago hotel room by a deranged female fan. I got some great recollections from Russ Meyer, who had been to dinner with Waitkus that evening. Waitkus was critically wounded but survived four operations to return to the Phillies as the regular first baseman in 1950. Russ told me that Waitkus ended up marrying his nurse and I printed it in the book. Wrong. Waitkus married a young woman he met on the beach during his rehab in Clearwater the following winter.

Without a doubt, however, one of the best interviews I conducted was with Russ Meyer, a/k/a as the Mad Monk during his playing days because of his volatile temper while on the mound. The stories about Meyer’s temper were legion and so I arranged to meet him at his home in Olgesby, Illinois, about 90 minutes outside of Chicago (By the way, Meyer was the only one who asked to be paid for his interview, although he quickly backed off when I told him I was financing these trips out of my own pocket. “Ah, come on up,” he said. )

Russ’s wife left to go shopping shortly after I arrived, leaving us to ourselves. I had been a little curious about what Meyer’s attire would be, since he’d been known as a real clothes horse during his playing days. Sure enough, although Meyer’s house was modest, at 72 he was resplendently casual in a grey v-neck sweater and bright plaid wool slacks.

At first, Meyer was a little wary, but he soon became comfortable with me and got into the swing of the interview. He had tremendous recall and could remember verbatim arguments he’d had with umpires, sprinkled with what I’m sure were the original f-bombs and other colorful language. I was there over three hours and emerged with wonderful material, as Russ was extremely candid and admitted doing any number of things that he regretted. So colorful was the language that when working on the book at home l had to make sure that none of my young daughters were around when I played his tapes.

Meyer had a number of run-ins with Jackie Robinson, who could get under Russ’s skin with his antics on the base paths. He even admitted calling Robinson the n-word. “Bad judgment on my part but I said it and I’m not going to deny it.” Meyer told me that when he was traded to the Dodgers before the 1953 season, he was initially very excited because the Dodgers were winning pennants and he’d likely be cashing World Series checks. Then he remembered with trepidation that he was going to have to walk into the Dodgers’ clubhouse and face Robinson.

Meyer then related that when he did walk into that clubhouse in Vero Beach at the start of spring training, the first person he saw was Jackie Robinson. “Oh, no,” he thought. Robinson saw Meyer, got up from his locker and walked over to Russ, put out his hand and said, “Monk, we’ve been fighting one another. Now let’s fight ‘em together.”

That’s striking gold for an oral historian. That type of interpersonal information is just not available without going to the sources. By the way, Meyer told me that he became fast friends with Robinson.

Two other wonderful Robinson stories that I unearthed came from Robin Roberts. It is well known that the Phillies were particularly hard on Jackie when he integrated the majors in 1947, fueled by racial invective from manager Ben Chapman and coach Dusty Cooke, both southerners. That Phillie team was mostly a veteran team, but the rough treatment of Robinson continued even into 1948 when the club began calling up some of the younger players who would form the nucleus of the 1950 pennant winners. Roberts and Curt Simmons both recalled an incident in Ebbets Field shortly after Robin was called up and shortly before Ben Chapman was fired as manager.

Robinson had helped the Dodgers sweep a doubleheader with seven hits and a couple of stolen bases. Afterwards, Chapman waited for Robinson under the stands where the runways from both dugouts met for a common tunnel to the dressing rooms. Roberts and Simmons were behind Chapman and when Jackie walked by, they heard Chapman say to him, “Robinson, you’re one helluva ballplayer, but you’re still a [n-word].” Roberts thought that if Robinson lit into Chapman, it would be a whale of a fight, since both were big strapping men, but Robinson, turning the other cheek, just looked at Chapman, and kept on walking.

A little over two years later on the last day of the season, October 1, 1950, the Phillies defeated the Dodgers in 10 innings for the pennant in a game the Dodgers seemingly had won in the bottom of the ninth inning. According to Roberts and others, in spite of that bitter loss and notwithstanding the way the Phillies had treated him when he broke into the league, Robinson visited the Phillies clubhouse after the game and went player to player to congratulate them on winning the pennant.

Thus, I learned more about Jackie Robinson’s character than I could have imagined simply by interviewing his rivals.

One person who was a must to interview was Richie Ashburn, the Phillies star center fielder who had thrown out the Dodgers’ Cal Abrams at the plate in the bottom of the ninth inning of that decisive game in 1950. The Dodgers had Abrams on second and Pee Wee Reese at first with no outs and Duke Snider at the plate. Ashburn was thought to have a weak arm and over the years the Dodgers and others had indicated that Ashburn was playing more shallow than usual in case Snider bunted or the Phillies tried to pick Abrams off second. Richie labeled both theories as “preposterous” because the Phillies didn’t even have a pick-off play at second and even in the unlikely event that Snider bunted the play would be at third or first, not second. He told me he did come in a couple of steps because the winning run was on second and simply raced in, caught Snider’s line drive on one hop and fired to the plate, just as he’d done in practice thousands of times before.

Abrams was out by a good 15 feet and the play cost Dodgers third-base coach Milt Stock his job, since he’d sent Abrams with no one out. Stock subsequently resurfaced as the third-base coach for the Cardinals and Ashburn recalled that he’d then thrown out three Cardinals at home in one game. Richie was known for his dry wit, and told me, “I guess he never thought I could throw.”

Ashburn of course was the beloved broadcaster of the Phillies games for 35 years after his retirement as a player. I’d driven down to Houston to interview him in his hotel room in the Galleria during one of the Phillies trips there to play the Astros. Near the end of the interview but with the tape still rolling, I asked Richie off-handedly how long he thought he’d continue to broadcast. He thoughtfully responded that the travel was very wearing, but that he thought he would really miss the games. He said he wasn’t sure how long he’d keep doing the games, but said, “I’ll tell you one thing, I don’t want to end up like Don Drysdale.”

Hall of Fame pitcher Drysdale was a Dodgers broadcaster who had died just two years earlier, alone in a hotel room in Montreal, Canada, while there to broadcast a Dodgers-Expos series.

Unfortunately, in September 1997, about two years after my interview with him and shortly after he’d finally been inducted into Baseball’s Hall of Fame, Whitey did meet the same fate, dying in a New York hotel room after broadcasting a Mets-Phillies game.

In reliving the glory of 1950 with the Whiz Kids themselves, I was able to experience their full range of emotions, and I became sort of an unofficial Whiz Kid myself since they all knew what I was up to. I developed friendships not only with my boyhood hero Roberts, but also with others such as Bubba Church, Andy Seminick, Curt Simmons, Richie Ashburn, Eddie Sawyer, and Putsy Caballero.

The culmination of these interviews was a book titled The Whiz Kids and the 1950 Pennant which Robin Roberts and I co-authored and which was published by the Temple University Press in late 1996. We wrote the book as seen through Robin’s eyes, but sprinkled it liberally with quotes from all the ballplayers and others whom I interviewed. So, for example, we had the recollections of all the participants of the key plays of the pennant-clinching game in Ebbets Field: Ashburn on his throw in the ninth to save the game, Stan Lopata who caught the throw and tagged out Cal Abrams, Robin who pitched the entire game, Dick Sisler who hit the legendary 10th-inning home run, and Del Ennis who caught the last out in the ninth in spite of losing the ball in the sun.

As a thank you I sent all the Phillies I’d interviewed a wonderful color lithograph of the Whiz Kids that a Philadelphia based sports artist named Stan Kotzen had produced, along with a copy of the book. I sent one of each to Mike Goliat, who’d effectively resisted my efforts to interview him, as well. Unexpectedly in return I received a note of thanks from Mike, a vintage baseball that he signed, and another piece of memorabilia autographed by several of his Whiz Kids teammates. Thereafter I received a Christmas card from the Goliats for as long as they were alive.

Unhappily time is of the essence when obtaining oral histories from old ballplayers. I conducted my interviews of the Whiz Kids about 20 years ago, or about 45 years after their pennant-winning season. Even then several members of the team had passed away including first baseman Eddie Waitkus; third baseman Willie “Puddinhead” Jones; pitchers Jim Konstanty (the National League MVP), Jocko Thompson (one of the most decorated paratroopers of World War II), Blix Donnelly, Jack Brittin; reserve catcher Ken Silvestri; and reserve outfielder Stan Hollmig. Now, however, only three survive, Curt Simmons, Putsy Caballero, and Bob Miller.

In retrospect, I’m just so glad that I did what I did when I did it. It took real time and money to fly around the country to talk to old ballplayers over about a three year period, but the memories I uncovered and the benefits that I received were, as the popular ad says, priceless.

PAUL ROGERS is co-author of several baseball books including The Whiz Kids and the 1950 Pennant (Temple University Press, 1996) with boyhood hero Robin Roberts, and Lucky Me: My 65 Years in Baseball (SMU Press 2011) with Eddie Robinson. Paul is president of the Ernie Banks – Bobby Bragan DFW Chapter of SABR and a frequent contributor to the SABR BioProject, but his real job is as a law professor at Southern Methodist University, where he served as dean of the law school for nine years. He has also served as SMU’s faculty athletic representative for 30 years.