That One Time When Willie Mays Wasn’t Perfect

This article was written by Rob Neyer

This article was published in Willie Mays: Five Tools (2023)

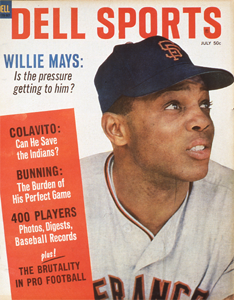

Some sportswriters in the 1960s worried that Willie Mays was actually hurting the Giants. One magazine headline asked, “Is Willie really worth $105,000?” (SABR-Rucker Archive)

If we didn’t have proof, we probably wouldn’t believe it. If there hadn’t been hundreds of magazines published in the 1960s about baseball, a large percentage of them containing articles and essays about Willie Mays and his San Francisco Giants, we probably wouldn’t believe that during the 1960s, there was a cottage industry seemingly devoted to blaming Willie Mays, arguably the greatest player ever, for the Giants’ failure to reach more than one World Series during Mays’ many years in San Francisco.

Because they had Willie Mays – along with stars like Orlando Cepeda, Willie McCovey, and Juan Marichal – the 1960s Giants were simply expected to win, or at least be tremendously competitive, every single year. Which they hadn’t been, early on. In their first three seasons in San Francisco, the Giants finished third, third, and (in 1960) fifth.

In 1961 Fawcett Publications published (at least) two preseason magazines, and both included stories (by different writers) headlined “What’s Wrong With the Giants?” Despite a new manager (Alvin Dark), the ’61 Giants finished third again, and afterward another Fawcett magazine included the story “The Truth About the Giant Troublemakers” (among them Willie Mays, but hardly anyone of note escaped suspicion).1

What’s wrong with the Giants?

As it turned out, nothing at all. At least not in 1962, when the Giants won 103 regular-season games (including two in a pennant playoff against the Dodgers) and missed winning the World Series by just a few inches (which broke Charlie Brown’s heart, among others).

They never returned to the World Series, though. Every fall for the rest of the decade, it was instead the Dodgers or the Cardinals or (just that once) the Mets. The Giants dropped back to third place in ’63 and fourth in ’64 (despite solid records that granted were inflated by expansion), then finished second in five straight seasons (1965-1969). They never came close to a losing record. In those seven post-Series years, the Giants won more regular-season games than any other National League team: Giants 635, Cardinals 634 (and Dodgers just 605, in case you’re wondering).

So were there “What’s wrong with the Cardinals?” stories when St. Louis didn’t win? No, not really. There were a few Dodgers stories like that in the late ’60s when they suffered two straight losing seasons. But even then, the stories were about the Dodgers … and not Don Drysdale or Walter Alston or Willie Davis. Whom I mention because in the wake of 1963’s third-place finish, a significant percentage of that early-’60s “What’s wrong” energy turned into “What’s Wrong with Willie Mays” energy.

Which in retrospect seems … crazy, right? Over the seven seasons from 1963 through 1969, Mays ranked third in the National League in home runs, fourth in runs scored, fifth in RBIs, and – not that we knew this until recently – first in Wins Above Replacement. In that latter category, Mays’s advantage is slight over Henry Aaron, Ron Santo, and Roberto Clemente. But you can at least make a reasonable argument that Mays was, during that stretch, the most valuable player in the National League despite being the oldest of those players by a fair piece. (He had three years on Aaron, more on the others.)

In 1964 the June issue of Sport World magazine included a Paul Donley-penned story, “Is Willie really worth $105,000?”2

That season he wound up leading the National League with 47 home runs, earned his eighth straight Gold Glove, and finished sixth in MVP balloting. But Mays did struggle during the summer, after a tremendously hot start, and finished with a .296 batting average, which set off alarm bells (note to younger readers: Baseball writers used to be utterly obsessed with batting averages, and specifically the value and meaning of .300-plus batting averages).

The next year, he hit a career-high 52 homers and won his second Most Valuable Player Award (and another Gold Glove). The Giants finished second.

Skipping ahead a few years, for just a moment … In 1971, an issue of Sport Scene magazine included an article, “Willie Mays Is Hurting the Giants!”3

How exactly was he doing this? “Usually no man wins or loses a pennant by himself,” the story read, “but an overreliance on Mays may very well have cost the Giants one or more flags.”4

Let’s assume for the moment that Willie Mays was the greatest player of the 1960s (practically inarguable), if not the greatest player ever (arguable, with Babe Ruth and Mays’ godson Barry Bonds having vastly different arguments). Why, year after year, would the writers of the time look toward him for explanations of the Giants’ supposed failures?

Bill James observed, a few decades ago and not really so long after Mays’ career ended, that the media often focuses on a team’s best player to explain its failures. He wasn’t writing specifically about Willie Mays and I don’t know if James read those magazines in the 1960s. But I doubt if you could find a better exemplar of Bill’s theory.

Mays was a target for the writers mostly because he was the biggest, easiest target. He was the Giants’ best player, obviously, and also their longest-serving; he was there before Marichal and McCovey showed up, and he was there well after Cepeda left. Mays played (in San Francisco) for managers Bill Rigney, Tom Sheehan, Alvin Dark, Herman Franks, Clyde King, and Charlie Fox.

In fairness to the writers (and editors), Mays was more than just his tremendous statistics. During the 1964 season, manager Alvin Dark named Mays the first Black team captain in American League or National League history, and Mays would later write about taking charge of positioning not only the outfielders who flanked him, but also the infielders.5

It’s not clear that Mays was emotionally suited to that role, though; it seems he already had more than enough on his mind.

In 1964, the San Francisco Chronicle’s Bob Stevens wrote of Mays (in yet another preseason magazine): “Willie plays the game too hard to last fantastically long. He never relaxes. On defense he literally plays three fields; on offense he hits with the best of them, better than most; on the bases he runs with more electrifying derring-do than any of them and he directs traffic, too. And he has collapsed twice from sheer exhaustion, once in ’62 and once in ’63.”6

It was probably more than twice. In both 1957 and ’58, Mays spent two or three days in the hospital. There were references to viruses, exhaustion, various other maladies, but Mays might have best explained his various hospitalizations, usually (but not always) in the middle of seasons. There were hospital stints in later seasons, too.

In 1958 he told reporters, “I need help like anybody else. I try not to worry too much, but I’m human too.”7

In 1959 Mays was quoted in Sport magazine: “When I’m in a slump, people ask me so many questions that I go into the hospital and have nobody bothering me. If I could get the same privacy somewhere else, just a complete rest, I wouldn’t go to the hospital.”8

In 1967 he told Sports Illustrated, “Some guys can go 0 for 4 the way I have and lose the way the Giants have and then go home and sleep. Not me. I worry. They pay me to win and when I don’t win, I worry and don’t sleep.”9

Oh, those famous (at the time) slumps. In a 1962 issue of Inside Sports, featuring Mickey Mantle’s Baseball Magazine, Ed Stacy wrote, “For all his abundant talents, the ‘Say Hey Kid’ himself has suffered, from time to time, the agonies of a batting slump. Warren Spahn of the Braves explained this once by saying, ‘Willie, despite his greatness, makes more mistakes at bat than any good hitter in baseball.’”10

Sounds like a weakness that Spahn, among the greatest pitchers of the era, could have taken good advantage of, no?

In fact, Mays faced Hall of Famers Spahn and Don Drysdale far more times than anyone else; he batted .305/.368/.587 against Spahn, and .330/.374/.604 against Drysdale. In 24 All-Star Games over the course of 20 years, Mays batted .307/.366/.533 against the best pitchers American League managers could throw at him.

The notion that Mays was particularly slump-prone showed up again and again, though; the 1963 True’s Baseball Yearbook – yet another Fawcett publication – mentioned in passing “his periodic hitting slumps,” and this came up again and again in contemporary stories about Mays.11 Of course nobody actually checked to see if Mays was any streakier than other superstars who played nearly every game. But if he was streaky, his insistence on playing through a multitude of minor injuries might well have led to the occasional slump, which (since it was Willie Mays) everyone noticed. And asked him about.

He never really slumped in 1962, but he did collapse in September and spent a few days in a Cincinnati hospital. “His sudden collapse late in the season,” True’s Baseball Yearbook wrote, “was attributed by doctors to Willie’s turbulent personal emotional life. He had recently gone through a divorce from his wife, Margheurite, and the strain of keeping his private tensions locked up inside while he carried the pressures of being a super-ballplayer simply was too much for him, or any human being, to bear.”12

After the Giants finished fourth in 1964 – a season in which Alvin Dark created an ethnically charged situation that ultimately led to his firing – Dell Sports magazine wrote of Dark’s replacement,

Herman Franks has inherited the massive headache. He is a manager in the Durocher tradition: bold, aggressive, fearless, and talkative. He also has one other Durocher characteristic, which could serve him better than all others in this particular situation: he knows how to blow smoke up Willie Mays’ nostrils.

Al Dark couldn’t do that, and if he could, he wouldn’t. Al Dark figured Willie Mays was a great ballplayer without having to be told it every day, so Al Dark didn’t tell it to Willie Mays every day. To Willie Mays, this was a clear indication that Alvin Dark didn’t like him, so Willie Mays batted less than .300 for the first time in eight years, and there were days, during the pennant drive, that Willie Mays was too tired to play at all.

Willie Mays is a great ballplayer, and if he requires a daily confidence-builder, he can paste this on his wall and read it daily:

WILLIE MAYS, YOU ARE GREAT

Still, Herman Franks has a plan to work with Willie. “I will give him occasional rests during the middle part of the season,” says the new manager, “so he won’t get in the state he was in during September of this past season.”

It must go a bit beyond that. Franks, or someone, just convince Mays that when a man reaches 34, which Willie does in May, certain muscles and glands require more care and more rest.

“You cannot dance all day,” observed a critical Giant teammate, “and play ball at night.”13

Read that once or twice extra, and you might guess that entire observation is one long euphemism. To which we might respond, good luck with that, buddy.

A few months later, the cover of Official Sports Magazine (Baseball ’65) included a banner across the top: SPECIAL – HOW WILLIE HAS FAILED THE GIANTS. Inside, writer John Bergen identified six “major raps” against, you know, the greatest baseball player on the planet at that moment: “1) His withdrawal from teammates; 2) His unorthodox relationship with his managers; 3) His sensitivity to criticism; 4) His strained relationships with the press; 5) His annual exhaustion; 6) His curious brand of leadership.” Next come approximately 3,000 words explicating all these deficiencies, whether perceived or real.14

Also in the middle of the 1965 season, the first (and only?) issue of Baseball in Action magazine ranked Mays as the National League’s top center fielder, naturally. But every player in the positional rankings did get assigned one weakness. Mays’? “Puts forth such a total effort that he runs risk of physical exhaustion during course of a season.”15

It wasn’t that all these magazines, which presumably inflated claims and arguments in the interest of selling more magazines, were always (or usually) right. Earlier in ’65, one of the preview magazines opined, in somewhat blaring font size, that the Phillies “can’t lose, now that Belinsky’s here.”16 But they did reflect, at least to some degree, the opinions of the men who wrote them, and we must assume they helped form popular opinion of baseball’s teams and players. And all the above is just a sampling. Other examples from the era:

Willie Mays is Headed for Disaster (1962)

How Trouble Has Changed Mays and Mantle (1963)

What’s Left for Willie Mays? (1964)

How Sick Is Willie Mays? A Penetrating Analysis (1964)

The Brass Has Put Too Much Pressure on Mays (1966)

They’re Asking the Impossible of Willie (1966)

Again, just a sample! (I’ve got a whole bunch of those 1960s magazines, but hardly all of them.)

You’ve heard the old joke about the job interview? Interviewer asks that ridiculous question – “What’s your biggest weakness?” – and instead of answering honestly – “I get raging drunk every night, I always wind up hating my boss within two weeks,” whatever – you say something like “I guess I just care too much about doing a good job.”

If Willie Mays had a weakness, it might have been that he cared just a little too much. “Filled with nervous energy,” biographer James Hirsch wrote, “Mays seemed incapable of relaxing in between the white lines.”17 If he’d cared just a little less, if he’d been able to relax some, he might have been a little healthier, a little happier. If he were playing today, he’d get a day off every few weeks; he’d have someone to talk to about his worries and his troubles.

But instead he played more often than he should have, and he kept things bottled up. Still, for a lotta years nobody played better, and the San Francisco Giants were exceptionally fortunate to have him. Second place, and magazine writers, be damned.

ROB NEYER is the author or coauthor of eight baseball books, including the CASEY Award-winning “Power Ball: Anatomy of a Modern Baseball Game.” Rob lives in Oregon with his wife and daughter, and has been the commissioner of the West Coast League, the West’s premier summer collegiate baseball league, since 2018. He’s been a SABR member since 1985.

NOTES

1 Bruce Lee, “The Truth About the Giant Troublemakers,” Official Baseball Annual, 1962.

2 Paul Denley, “Is Willie Really Worth $105,000?,” Sport World, June 1964.

3 James S. Hirsch, Willie Mays: The Life, The Legend (New York: Scribner Books, 2010), 498-499.

4 Hirsch, 498-499.

5 Willie Mays and Lou Sahadi, Say Hey: The Autobiography of Willie Mays (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1988), 158-159.

6 Bob Stevens, “National League All Stars,” Sports All Stars 1964 Baseball, 1964.

7 “Big Man of the Giants,” Baseball’s Best, 1960.

8 Dick Young, “What About Those Willie Mays Rumors?,” Sport, May 1959.

9 Mark Mulvoy, “Say Hey No More,” Sports Illustrated, August 7, 1967.

10 Ed Stacy, “The Stars Tell How They Break ‘The Slump Barrier,’” Inside Sports, Featuring Mickey Mantle’s Baseball Magazine, June 1962.

11 “8 of the Best: A Color Portrait Gallery,” True’s Baseball Yearbook, 1963.

12 “8 of the Best: A Color Portrait Gallery.”

13 Dick Young, “Dick Young’s National League Outlook for 1965,” Dell Sports, March 1965.

14 John Bergen, “How Willie Mays Has Failed the Giants,” Official Sports Magazine (Baseball ’65), October 1965.

15 Joe Reichler, “The Best in the Business,” Baseball in Action, July 1965.

16 Official Sports Magazine (Baseball ’65), June 1965.

17 Hirsch, 357.