The 1908 University of Washington Tour of Japan

This article was written by Carter Cromwell

This article was published in Nichibei Yakyu: US Tours of Japan, 1907-1958

1908 University of Washington and Waseda teams. (Rob Fitts Collection)

Links between Japan and the Seattle area are nothing new. They were first forged in the late nineteenth century when Japanese began immigrating to the Pacific Northwest, and they’ve strengthened over the years. One of the consequential connections has been baseball.

In 1905 a team from Japan’s Waseda University toured the American West Coast and played against various US teams. That led to a trip to Japan three years later by a group of a dozen University of Washington players, and those two journeys set the stage for frequent travels by Japanese and Seattle teams. The 1914 Seattle Nippon was the first Japanese American club to go to Japan, and the 1921 Suquamish Tribe became the first Native American team to do so. Teams from the University of Washington also made trips to Japan in 1913, 1921, and 1926 (and then returned 55 years later, in 1981). Before World War II, 13 clubs from the Pacific Northwest traveled to Japan, and about a dozen Japanese university teams made the reverse trip.1 The 1908 University of Washington tour was the first US collegiate tour of Japan and the first by a mainland US team. It was made possible by arrangements completed by Professor Isoo Abe, a Japanese college athletic instructor who had been the driver behind Waseda’s trip to the United States in 1905.2 Professor Abe—known in Japan as the “Father of University Baseball”—had been impressed by the hospitality shown by the University of Washington and the Seattle residents during the 1905 visit. In addition, the University of Washington had accepted the largest number of Japanese students in the United States at the time and was familiar to the Japanese people.3

Abe had persuaded his university to subsidize the 1905 tour, despite the fact that Japan was fighting a war with Russia at the time.4 Baseball historian Kerry Yo Nakagawa said, “From a baseball standpoint, [Waseda was] the best team in Japan, and they wanted to test the water of American baseball at the university level. They wanted to dissect the American game, use it as a laboratory to learn.”5

Three years later, that still held true, and Waseda invited the University of Washington to come to Japan. Washington did not send its official team, but all 11 players making the trip had played for the Huskies and were from the state of Washington. They included first baseman Webster Hoover of Everett, pitcher Huber Grimm of Centralia, right fielder Byron Reser of Walla Walla, second baseman Arthur Hammerlund of Spokane, catcher Roy Brown and pitcher Earle Brown of Bellingham, third baseman Ralph Teats and center fielder Leo Teats of Tacoma, and shortstop Walter Meagher, pitcher Ed Hughes, and left fielder Percy Logerlof of Seattle. Howard Gillette managed the team.6

The team had been scheduled to leave Seattle on September 1. Instead, it left on the vessel Tosa Maru on August 18, and docked in Yokohama on September 3, much earlier than expected and 16 days prior to the first scheduled game, so there were few Japanese there to greet the team. One of the Washington players said they had come earlier to visit attractions that their fellow Japanese students had told them about, and they also wanted to have time to prepare since they knew that the Keio team had played well during a recent tour of Hawaii.7

Game 1 was scheduled for September 19, and the buildup began immediately.

The Jiji Shinpo newspaper wrote, “We usually think that most American baseball teams are professional teams. However, they are college students and do not play baseball for money. Probably because of that, those twelve men are very graceful youngsters with high spirits. They wore fine suits and a golden ring with a diamond and looked very handsome.” The newspaper also rated the University of Washington as the third-best college team in the United States behind Yale and Harvard, though the source of that rating is unknown.8

Some 2,000 spectators watched Washington’s first practice. The Tokyo Asahi Shinbun wrote that the practice “drew more spectators than some official games,” adding that “since [the Washington players] have been training hard in baseball’s mother country, their movements in fielding practice were very steady and also dynamic.”9

Writing in the 1910 university yearbook, the Tyee, shortstop Walter Meagher said the players were surprised to see so many people at the initial practice. “We were so stage-struck that we didn’t practice as long as we intended. Soon, however, we got so used to the crowds that we were disappointed if they did not come.”10

Ticket prices ranged from 20 sen to 50 sen (a currency demonetized at the end of 1953) and were sold at seven locations in Tokyo.11 A sen was worth one one-hundredth of a yen. Between 1897 and December 1931, the yen’s value was frozen at 50 US cents. Therefore, the most expensive tickets cost a half-yen, or 25 US cents. Though the Japan Times called the 50-sen cost “a large sum” in one article,12 it also said that “those interested in the sport would not afford to miss such a fine treat, and we hope that the days will be favoured with beautiful weather.”13

The Japan Times also reported that “[u]ncommon interest is aroused by the baseball match to be played on the Waseda ground between Waseda and [the] Washington University team. Tickets for spectators have been issued to the number of 15,000 for that day; still the number is considered inadequate to meet the demand.”14 Even “the Americans resident in Yokohama will come up to town by a special train to Mejiro to see the baseball game at Waseda. They will root for the Washington team.”15

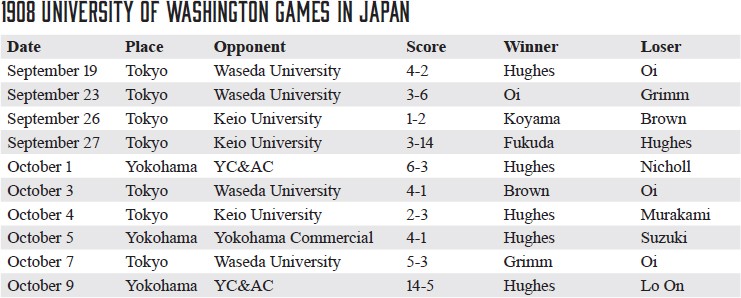

Poor weather unfortunately kept many fans away when the series got under way on September 19, but many people—variously reported as 6,000 or 7,000—showed up despite clouds and drizzling rain. They saw Washington rally with three runs in the eighth inning to overcome a 2-1 deficit and win 4-2.

Washington got a run-scoring triple by center fielder Leo Teats, an RBI single by Reser, and an error by Waseda left fielder Moriichi Nishio. The visitors’ other run had come in the third inning when Webster Hoover scored on a passed ball by Masaharu Yamawaki. Takeshi Iseda’s third-inning sacrifice bunt and Yamawaki’s single in the sixth that scored Iseda accounted for Waseda’s two runs.16

According to the Seattle Daily Times, “Captain Edward F. Hughes, of the U of W team” wrote that “Washington won … but had to keep moving all the time. The University only obtained three hits off the Waseda pitcher and these came in a bunch in the same inning, netting three runs. The Nipponese were lightning fast on their feet and are accurate fielders.”17

A reporter for the Jiji Shinpo overheard two students talking after the first game. One said that Washington had lost badly to the University of Santa Clara, which had easily defeated Keio in an exhibition game. “Now I understand why they didn’t play as well as we expected. … They are not as good as St. Louis [the Hawaiian semipro team that had toured Japan in 1907], for sure. The Waseda team will win the next game.”18

He was right.

Game 2 was scheduled for the next day, but heavy rain forced its postponement to September 23. When the game finally commenced, Washington scored single runs in the third and fifth innings, while Waseda got one in the fourth, so the Huskies carried a 2-1 advantage into the last half of the eighth inning. Then Waseda broke through with five runs en route to a 6-3 victory. The hosts scored once on a bases-loaded error by UW first baseman Hoover, a two-run single by Kinichiro Shishiuchi, and two more on a throwing error by shortstop Meagher.

The Japan Times observed, “One fault of the American boys is that they become easily confused when the game is unfavorable to them. But they have many strong points. They talk boisterously when in the field, while Waseda boys are very silent. Keio boys are said to imitate the American players in this noisy talking, but we rather think the Japanese method is more becoming to the Japanese.”19

Game 3 of the series matched Washington against Keio on September 26 and was “an interesting game” before “a large assembly of spectators,” according to the Japan Times. Each team scored a run in the first inning. Eizo Kanki’s fly out for Keio scored Katsumaro Sasaki, and the Huskies countered with Grimm’s double that drove home Hoover. Keio went ahead 2-1 in the fourth inning when Kanki stole home—or, as the Japan Times story put it, “Kanki made an adventure and got home.” The article further revealed that “Washington made strenuous efforts to recover arrears, but their efforts were frustrated by the excellent fielding of Keio. … The game closed with 2 to 1 in favour of Keio.”20

Game 4 the following day again matched Washington and Keio, and it was the polar opposite of the previous day’s low-scoring affair. This time, Keio took a 6-1 lead after four innings and then scored five more runs in the fifth inning en route to a 14-3 victory. Nenosuke Fukuda, Yokote, Katsu, Sasaki, and Tokuichi Takahama all scored in Keio’s decisive fifth-inning outburst.21

The Japan Times reported, however, that the “Washington boys … endured the defeat with good grace and admirable fortitude. Pitcher Grimm when deposed to center went thither with quite amiable good humour. The sympathy of all spectators were with the vanquished and they often cheered for them.”22

By then standing 1-3 on its tour, the Washington team had a four-day break before playing its next game, against the Yokohama Cricket & Athletic Club, a team made up of Americans, on October 1. Each team scored twice in the first inning, but Washington took control with a three-run third inning, as Leo Teats, Grimm, and Meagher crossed the plate. Yokohama got a run in the sixth inning, and UW scored once in the seventh to account for the final 6-3 score. The Japan Times wrote that the “game was perhaps the best ever played in Yokohama.”23

Two days later came a rematch between Washington and Waseda, with the Huskies taking a 4-1 victory to even their record on the trip at 3-3. Hoover, Leo Teats, and Meagher scored in the fourth inning for Washington, and Hammerlund crossed the plate in the seventh. Yamawaki scored Waseda’s only run in the fourth inning. In contrast to its coverage of previous games, the Japan Times printed only a one-paragraph story about this game and reported that “Waseda batters were remarkably idle.”24

The next day Washington again played Keio and again lost, this time by 3-2, making the Huskies 0-3 against Keio on the tour. Kanki, Denji Murakami, and Ryokichi Sawahara scored for Keio in the first, fourth, and seventh innings, respectively. Hoover singled and later scored for UW in the sixth inning. In the ninth, he tripled and later came across to pull his team to within one run, but the Huskies could get no closer.

The Seattle Post-Intelligencer noted that Keio was a “stumbling block” for the “tourists. … The Keio players had returned home from a ballplaying tour of the Hawaiian Islands and were in perfect training. The Washington players entered the games stale and out of shape from climactic conditions.” Team manager Gillette was quoted as saying, “Our pitchers were considerably distressed by bad arms throughout all our stay in Japan, but … there was not a game in which we did not get more hits than our opponents.” (Keio actually outhit Washington twice.)25

A day later, UW took a 4-1 victory over the Yokohama Commercial School, as Hoover and Grimm scored first-inning runs, Ralph Teats crossed the plate in the fourth, and Meagher came across in the fifth.

On October 7 Washington and Waseda again played, with UW winning 5-3 in 15 innings. Washington opened with a run in the first inning. Waseda scored twice in the second inning to take a 2-1 lead, but UW tied the game in the fourth inning. The score remained tied, 2-2, until each team scored a run in the 12th. Washington finally got the game-winning runs when Ralph Teats and Hoover crossed the plate in the 15th inning. According to the 1910 University of Washington yearbook, the Tyee, “Meagher described the victory as the best game ever played in Japan.”26

The Washington team concluded its 10-game tour on October 9 with a 14-5 victory over the Yokohama Cricket & Athletic Club. Yokohama scored four runs in the first inning to take a 4-0 lead, but UW scored three times in the second inning, once each in the third, fifth, and sixth, and then twice in the seventh for an 8-4 advantage. Then came a six-run rally in the eighth inning that put the game out of Yokohama’s reach. Ralph Teats, Hoover, Leo Teats, Meagher, Reser, and Roy Brown all scored for Washington in the decisive inning.

The Washington team began its 15-day trip home on October 10. As reported by the Japan Times, “The baseball team from the University of Washington … who has given such a splendid series of baseball games in Tokyo and Yokohama[,] left Yokohama for home by the … steamer Tosa Maru yesterday. … Teams from Waseda and Keio Universities … and others saw the party off. The Washington boys looked very brilliant and happy in their school uniform. When the ship was to weigh anchor, Waseda and Keio college yells were given, and [the] Washington team replied with their college yell. The ship sailed amid hearty wishes of bon voyage of the home teams.”27

In his master’s thesis, “Seattle and the Japanese- United States Baseball Connection, 1905-1926,” Ryoichi Shibazaki writes that “when Ichiko defeated the Yokohama Athletic Club in 1896, the Japanese people took it as the victory of the Japanese over Americans, rather than a simple win in baseball. In so doing, the Americans were treated like the enemy by the Japanese media. However, the Japanese people and media treated the Washington team fairly and warmly. … [I]t suggests that the Japanese people had adjusted to the Western culture fairly well by that time and could abandon the hostile feeling toward the American people who were often treated as ‘invaders’ a decade before.”28

Indeed, between their arrival and their first game, the Washington players were squired around Tokyo and visited temple sites, attended a theater performance, and met politicians. “We were royally entertained by Count Okuma, the great Japanese diplomat [and founder of Waseda University], who showed us about his garden and magnificent mansion,” Meagher wrote in the school’s yearbook.29

The trip was considered a rousing success. It was said that the total attendance for the 10 games was 70,000, and the attendance for the first game—variously reported as either 6,000 or 7,000—came despite the drizzling rain much of the time.30 Reportedly, crowds of 9,000 people showed up for two of the games with Waseda.31

“We arrived home Oct. 25, all in good health and feeling we had one of the greatest trips that any college team had ever taken,” Meagher concluded.32

Gillette, the Washington manager, said, “The Japanese boys played better ball than we thought they would, and our work was hardly up to standard. The Japanese players proved the shiftiest men on their feet I have ever seen on a baseball diamond, and their fielding was probably superior to that of the average American amateurs.”33

In the same article, the Seattle Evening Star fully acknowledged the Japanese baseball prowess, though in a manner that indicated Americans’ prevailing attitude at the time toward Asians and Japanese in particular—“It is an indication of the Jap’s adaptability that he defeated the Americans four times out of ten. He simply beat the Americans at their own game.”

Gillette added, “Our reception by the Japanese from the hour we left Seattle could not have been more cordial. Every detail and arrangement was carried out harmoniously and the cordiality provided makes us all feel that Japan’s ball players and their loyal fans constitute sportsmen to emulate.”34

An article in the Seattle Post-Intelligencer reported that “the entire press of Japan treated the visit of the American ballplayers as the one big athletic incident of the year.” There was “intense interest … and every detail of the game was studied with care.” The story added that “the spirit of fairness … was the subject for favorable remark by each of the returning players,” and it also said that “from the standpoint of closer athletic relations with Japan, the trip is reported as peculiarly successful.”35

Okuma, the Japanese diplomat, “gave a dinner at which he delivered an address highly commending the spirit of athletics and expressing a wish for an extension of the tests of skill between his people and Americans.”36

Meagher, the team’s shortstop, wrote that “We … took a short trip to Nikko, the great temple site of Japan. … This was one of the finest visits we had while in Japan. … We attended a Japanese theatre a few nights afterwards. … Ushers conducted us to chairs in the first balcony, prepared especially for us. We could not understand much about the play, but the acting and scenery interested us a great deal.”37

Shibazaki wrote that while the impact of the UW tour “on Japanese baseball, culture, and politics was almost invisible,” it did “set a precedent for other American colleges such as the University of Wisconsin, University of Chicago and Stanford University.” Teams from those schools, as well as the University of Washington, visited Japan in later years “and became main figures in the Japanese-United States baseball connection during this decade.”38 Additionally, since the 1908 tour, bonds between UW and the Waseda and Keio universities have steadily grown. There are currently four programmatic relationships between Washington and Waseda.39 As well, Washington and Keio have “inclusive exchange programs at the undergraduate and graduate levels. For many years, comprehensive agreements between the Universities’ Schools of Pharmacy, Nursing, and Law have enabled the institutions to work together in teaching and research.”40

CARTER CROMWELL is a former sportswriter for daily newspapers and a corporate public-relations professional. He works with an independent-league baseball team and contributes baseball-related articles to various websites. When not doing that, he has a passion for world travel, photography, and rescue dogs.

NOTES

1 John Rosapepe, “A Pastime with a Past,” Seattle Times, March 20, 2003. https://archive.seattletimes.com/archive/?date=20030320&slug=japan2o; Columns Staff, “Husky Baseball Is No Stranger to Globetrotting,” University of Washington Magazine, March 1, 2019. https://magazine.washington.edu/husky-baseball-is-no-stranger-to-globetrotting/.

2 “University Boys Tell of Japan’s Baseball Spirit,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, October 26, 1908: 1.

3 Ryoichi Shibazaki, “Seattle and the Japanese-United States Baseball Connection, 1905-1926,” Master of Science Thesis, University of Washington, 1981, 40-41.

4 Robert K. Fitts, “Baseball and the Yellow Peril: Waseda University’s 1905 American Tour,” Baseball 10 (2018): 141-159.

5 Rosapepe.

6 Walter Meagher, “The Japan Trip,” The 1910 Tyee of the University of Washington (Seattle: University of Washington, 1910), 148.

7 Shibazaki, 41.

8 Shibazaki, 42.

9 Shibazaki, 42.

10 Meagher, 146.

11 Shibazaki,43.

12 “Baseball at Waseda: Initial Victory for Washington,” Japan Times, September 20, 1908: 2.

13 “Baseball Match Between Washington and Waseda Teams,” Japan Times, September 16, 1908: 3.

14 “Waseda Baseball Display,” Japan Times, September 18, 1908: 6.

15 “Baseball,” Japan Times, September 19, 1908: 3.

16 “Baseball at Waseda: Initial Victory for Washington.”

17 “Washington Takes First Game,” Seattle Daily Times, October 12, 1908: 11.

18 Shibazaki,44.

19 “Waseda Baseball: Collapse of Visitors,” Japan Times, September 25, 1908: 6.

20 “Baseball at Waseda: Keio Defeats Washington,” Japan Times, September 27, 1908: 2.

21 Yokote’s and Katsu’s first names are unknown.

22 “Keio-Washington Baseball: Washington’s Disasters,” Japan Times, September 29, 1908: 6.

23 “Baseball at Yokohama,” Japan Tim, October 2, 1908: 2.

24 “Waseda Baseball,” Japan Times, October 4, 1908: 6.

25 “University Boys Tell of Japan’s Baseball Spirit,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, October 26, 1908: 1.

26 Columns Staff.

27 “Washington Baseball Team: Departure from Yokohama,” Japan Times, October 11, 1908: 2.

28 Shibazaki, 44-45.

29 Meagher, 148.

30 “Japanese Teams Defeat Americans,” Seattle Evening Star, November 2, 1908: 13.

31 “University Boys Tell of Japan’s Baseball Spirit.”

32 Rosapepe.

33 “Japanese Teams Defeat Americans.”

34 “Japanese Teams Defeat Americans.”

35 “University Boys Tell of Japan’s Baseball Spirit.”

36 “University Boys Tell of Japan’s Baseball Spirit.”

37 Meagher, 146.

38 Shibazaki, 45.

39 “Connections between the UW and Waseda University” Japan Studies Program, University of Washington, February 17, 2017: https://jsis.washington.edu/japan/news/connections-uw-waseda-university/.

40 “Japan’s Keio University and the University of Washington Launch a Dual Masters Law Program,” Asia Matters for America, June 13, 2017: https://medium.com/asia-matters-for-america/japans-keio-university-and-the-uni-versity-of-washington-launch-a-dual-masters-law-program-aoa7ic339d9.