The 1913-1914 Chicago White Sox-New York Giants World Tour

This article was written by Stephen D. Boren - James Elfers

This article was published in Nichibei Yakyu: US Tours of Japan, 1907-1958

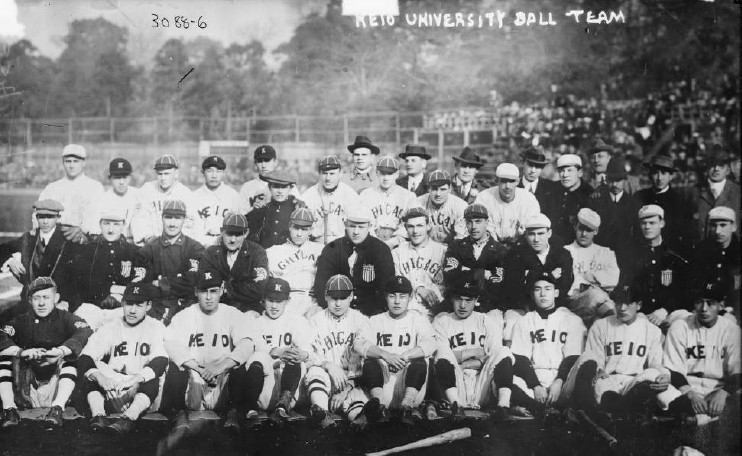

Keio University with the New York Giants and Chicago White Sox on December 7, 1913. (Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division)

INTRODUCTION

On January 27, 1913, John McGraw of the National League champion New York Giants and Charles Comiskey, owner of the American League Chicago White Sox, announced their plans for a world tour to be held after the 1913 World Series.1 The tour would be modeled after the 1888-1889 “Great Baseball Trip Around the World” when A.G. Spalding’s Chicago National League Club, led by captain Adrian “Cap” Anson, and a team selected from the National League and American Association by John M. Ward traveled the globe playing in New Zealand, Australia, Ceylon, (Egypt, and Europe.2 When Comiskey heard of the Spalding world trip he supposedly stated, “Someday I will take a team of my own around the world.”3

The tour would begin in Cincinnati and the teams would barnstorm across the country until they reached Vancouver, British Columbia, on November 19. From there, they would sail to Japan, China, the Philippines, Australia, Ceylon, Egypt, Italy, France, and the United Kingdom, before returning to New York on March 6, 1914. Comiskey’s close friend Ted Sullivan, a former manager and minor league executive, was named the advance scout to organize the tour, and sailed from San Francisco to Honolulu, Japan, and Australia. While Spalding’s tour had supposedly broken even, Sullivan felt that this one would make money. A few months later, Comiskey’s advance agent, Dick Bunnell, sailed for Europe to complete the arrangements on that continent.4

In June 1913, after White Sox manager James Callahan “called on President Woodrow Wilson to explain the proposed world tour … Wilson expressed his approval not only because he said he considered himself a base ball fan, but because he thought the movement might result in the creation of an international league.”5 Wilson also thought the tour might help advance international peace and amity.6

Many New York players were not enthusiastic about the proposed tour. The original plan required each person to personally put up $1,500 for expenses and for all to share equally in the profits. The players thought it would be a great trip but too expensive.7 The sponsors understood the players’ reluctance to make the financial commitment. McGraw initially refused to discuss the trip until the Giants were sure of winning the pennant and thus a share of the World Series money, until on July 29 he held a team meeting and for the first time officially informed his players of the world tour. He showed them the financial arrangements and received a large number of positive commitments, from Christy Mathewson and Chief Meyers among others. Meanwhile, Comiskey and Callahan began contacting players from other American League teams in case their players refused to go under the proposed conditions.8

On September 24 Charles Comiskey announced that 75 people would go on the World Tour. Each player would be required to post $300 to guarantee his appearance on the ship but once on board, the money would be refunded. For such an unprecedented tour with so many passengers, great logistic and fiscal planning was needed, and both Comiskey and McGraw were prepared to write checks of $100,000 to defray additional expenses.9

On October 7 Harry M. Grabiner, Comiskey’s personal representative, announced that he was finalizing the plans for the massive around-the-world trip. He said he expected the tour to be the largest sporting event ever. Preliminary reports from foreign countries suggested that baseball would be a worldwide topic before the players returned home. Grabiner said he had multiple requests for exhibition games from American Western cities. The tour was advertised like a circus with long billboard posters. Arrangements were made to film the games in foreign cities, as well as life on the ship and receptions with foreign monarchs and ambassadors.10

The tour left Chicago on the night of October 19 on a special train of five all-steel cars including an observation car and a combination baggage and buffet car. This traveling hotel was the party’s home as they barnstormed across the Midwest and West Coast, playing 31 games in 27 cities, before sailing for Japan from Vancouver a month later.11

By the time the teams reached Vancouver, their rosters had shrunk. Christy Mathewson and Chief Meyers decided not to accompany the teams across the Pacific. To even the squads, the White Sox loaned Urban “Red” Faber to the Giants.12 The final Giants roster consisted of pitchers Bunny Hearn (Giants), George Wiltse (Giants), and Faber (White Sox); catcher Ivey Wingo (Cardinals); first baseman Fred Merkle (Giants); second baseman Larry Doyle (Giants); third baseman Hans Lobert (Phillies); shortstop Mickey Doolin (Phillies); and outfielders Lee Magee (Cardinals), Jim Thorpe (Giants), and Mike Donlin (Giants).13

Of the 11 “New York” players, there were only three pitchers. There were no backup infielders, outfielders, or catchers. Counting Mike Donlin, who did not play in the major leagues in 1913 (he did return to the Giants in 1914), there were only six actual members of the New York Giants, and of those six, only Merkle and Doyle were regulars. Hearn had been in only two games (1-1 record) and Wiltse had not won a single game.

In the end, few of the White Sox players were willing to go. Of the 13 players on the roster, only six were White Sox and one was manager Callahan, who had played in only six games all season. There were three pitchers but no backup infielders. The official “White Sox” roster consisted of pitchers Jim Scott (White Sox), Joe Benz (White Sox), and Walter Leverenz (St. Louis Browns); catchers Andy Slight (Des Moines, Western League) and Jack Bliss (Cardinals); first baseman Tom Daly (White Sox); second baseman Germany Schaefer (Washington Senators); shortstop Buck Weaver (White Sox); third baseman Dick Egan (Brooklyn Robins); and outfielders Tris Speaker (Red Sox), Sam Crawford (Tigers), and Steve Evans (Cardinals). Jack Bliss had previously been to Japan as a member of the 1908 Reach All-Americans.

Besides the 24 players, the party included McGraw; Comiskey; umpires Bill Klem and Jack Sheridan; Chicago secretary N.L. O’Neil; A.P. Anderson (manager of the tour); Dick Bunnell (manager and director of the tour); Ted Sullivan (author and lecturer); and Chicago newspaper writers Gus Axelson (Record-Herald) and Joseph Farrell (Tribune). There were also wives, McGraw’s personal physician, Dr. Frank Finley, several children, and other friends.14

On November 19, 1913, the tourists boarded the RMS Empress of Japan in Vancouver and began their journey across the Pacific. For 17 days, the passengers endured tossing seas, driving rains, and even a typhoon. Most of the players suffered from seasickness and some, like Tris Speaker and Red Faber, could barely eat.15 On December 6 they finally arrived in Yokohama, three days behind schedule. Prior to their arrival, only three American college squads and one professional team had traveled to Japan. The lone professional team, the Reach All-Americans, consisted mostly of minor-league players with a smattering of undistinguished major leaguers. McGraw and Comiskey’s clubs would showcase major-league stars to the Japanese fans for the first time.

THE LAND OF THE RISING SUN16

BY JAMES E. ELFERS

Nothing, absolutely nothing, prepared the tourists for the reception they received in Japan. More like a homecoming than greetings from a foreign nation, the docks were a riot of color, teeming with droves of fans and sportswriters. Japan was every bit as mad about baseball as was the United States. Under gray, raw skies, amid the crowd of rabid baseball fans, US consul general Thomas Sammons ferried out in a tug to be the first to greet the tourists. Accompanying Sammons were several Japanese officials and sportswriters who served as the welcoming committee. While the Japanese needed interpreters to converse with the players, many of them knew at least one American phrase, greeting the players with a big “Howdy!”17

The ballplayers found the local press corps every bit as savvy as their US counterparts. In an impromptu press conference, they asked penetrating questions and made pithy observations. “The great manager McGraw’s pin made of diamond on his necktie was shining with the rising sun,” wrote a reporter for Jiji Shimpo, a Tokyo daily.18 A reporter for the Keihin Press asked about game strategy: “What strategy would the managers employ against each other and against Keio University?”19

The Americans were more candid with the Japanese press corps than they had been with their own. When disappointed reporters asked why Mathewson had not come, the tourists replied, “He was a bad sailor and also he didn’t like the ship. We tried to bring him but he declined.”20

The Japanese press was also disappointed not to find Jeff Tesreau and Fred Snodgrass among the players disembarking from the Empress of Japan. Nonetheless, they dutifully listed the names of every player and other tourists in the party. The Japanese media were particularly taken with Comiskey. Witness this quote from the Keihin Press: “Callahan, the manager of the Chicago team, and Comiskey were in high spirits. He is a dauntless looking man who also looked the gentleman.”21

After making their way through the crush of well-wishers and reporters, some of whom had even boarded the ship to get interviews, the party made its way to customs and examinations by doctors. Some members of the party, especially the women, were a bit apprehensive at what to expect, but everyone sailed through. The processing completed; the tourists boarded rickshas to take them to the consul general’s residence. Germany Schaefer immediately dubbed them “gin rickeys” (a pun based on the then-current pronunciation of the word for the vehicles, “jinrickshas”).22

Comiskey, Callahan, and McGraw chose a different mode of transport. Accompanied by their families, they rode in automobiles to the consulate. Just as in the United States, every luxury materialized for the tourists’ use. The only tourist not enjoying himself was Red Faber, still languishing on board the Empress. The ship’s surgeons would not allow the former Iowa farm boy out of the sickbay until he was strong enough to rejoin his teammates.

After a brief meeting with consul general Sammons at his residence, it was back into rickshas and cars for the trip to the Grand Hotel. Throngs of Japanese tagged along behind the cars and rickshas to the consul’s residence. This same throng shadowed the tourists to the Grand Hotel. Rest was not on the agenda, however. About all the players had time for was to check in and change; a game was scheduled for that afternoon at the baseball grounds at Keio University. The players were forced to play even before they had lost their sea legs.23

Owing to the lateness of the arrival of the Empress, the tourists’ schedule in Japan had to be trimmed by two games. Cut were the games scheduled for Kobe and Osaka. Three contests remained, all of them in Tokyo.

For the players, just being in Japan was an accomplishment in itself. Joe Farrell noted, “The fans can now understand why base ball world tours are 25 years apart. It takes that long to forget the initiation on the Pacific.”24

Arrival at the Grand Hotel precipitated a flurry of activity. Joe Farrell sets the scene: “Arriving at the Grand, the lobby bore a resemblance to a Chicago department store in a bargain rush. The main floor was thronged with vendors of kimonos and mandarin coats. All the ladies were busy bargainers at once. The male members rushed to the nearest silk shirt stores to select material and get measured for the lightest kind of stuff, for it is only a week before the party will be sweltering near the equator.”25

After a very hasty lunch, the tourists dashed back to the rickshas and were delivered to the train station. Arriving a little after noon, the tourists were once again ferried by the human-powered craft to the ballpark at Keio University. Along the way, a wheel came off the ricksha carrying the Thorpes, tumbling the newlyweds into a Tokyo street, but uninjured. After dusting themselves off, the adventurous Iva and Jim climbed into another ricksha and continued their trek.26

Keio University was the most prestigious collegiate baseball power in Japan. In 1911 Keio sent its team to barnstorm against college teams in the United States. Now, two years later, they got a chance to play host. Keio was at first embarrassed about the condition of its field. Thinking that it did not compare to the fields they had seen in the States, either in size or amenities, T. Kimishima of the Keio Base Ball Association offered these words, “I hereby wish to make an apology to you, the greatest of all exponents of the game. It is in an embarrassed state of mind that the Association invites teams to have the use of this midget field, but at all events your welcome is not belittled.”27

After reassuring Kimishima that the field was better than 30 percent of the fields in the United States, the game began. The proceedings were so rushed that the ballplayers didn’t even get to work out beforehand. McGraw did treat the crowd to a game of shadow ball, which put the crowd into hysterics. This was the very first game of shadow ball the Japanese had ever seen, and it was the perfect icebreaker. The tourists found one element of conforming to local custom most amusing. The Japanese tradition of removing one’s shoes when entering a house meant that before and after the game, each player had to doff his spikes before entering the clubhouse. Wooden cloglike slippers were provided for navigating the clubhouse.28

The game was intensely covered by the Japanese media. Every Tokyo paper had at least one reporter there, and some papers sent as many as five. To everyone’s delight, the sun chose this moment to break through the clouds. The early December day became almost springlike and far more tolerable for both fans and players. After lots of picture-taking by the assembled news outlets, umpires Klem and Sheridan were introduced, and the ceremonial first pitch was thrown from the mound by President Eikichi Kamata of Keio University to consul general Sammons half crouching at home plate.

Five thousand citizens wedged themselves into Keio’s baseball grounds and cheered themselves hoarse. Space was at such a premium that many of the fans sat on bamboo mats crammed into any open plot of land. To the Americans, it was all very heady and overpowering. The intensity of the Japanese fans and their knowledge of the game impressed the Americans. Veteran sportswriter Gus Axelson claimed that they were every bit as loud as any group of Giants fans under Coogan’s Bluff.29

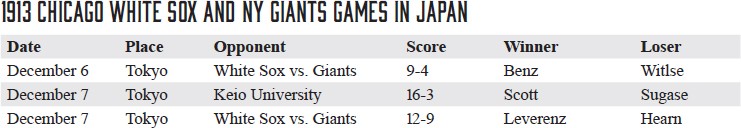

The Giants and White Sox played fair baseball considering how seasick everyone had been for so long, with the White Sox winning 9-4. The seasick Texan Tris Speaker had a great game, two home runs, and a couple of hard liners. The very short right- and left- field fences and the exotic atmosphere probably made everyone play much better than they felt.

Just as he had done in the States, Bill Klem, in his most windows-rattling bass voice, elaborately introduced each player as he strode up to the batter’s box. Klem’s mammoth vocal power, elaborate style, and pugnacious attitude were unlike anything the Japanese had encountered before in an umpire. Klem quickly became a favorite of both the crowd and the sports reporters. Just how much of an impact he made could be seen in the next day’s Jiji Shimpo. The paper had sent a caricaturist to the game to capture the day’s activities. Klem’s caricature was rendered larger than anyone else’s.

For Japanese fandom, the tour was nirvana. Although their nation had adopted baseball as its national pastime, no games of major-league caliber had ever been played there. A.G. Spalding had completely bypassed Japan 25 years earlier during his tour. Preferring to journey to nations under British or American rule, Spalding made his trail considerably more southern. From Hawaii, Spalding’s All-Stars sailed to New Zealand and Australia before dodging north to Ceylon, Egypt, Italy, France, and Great Britain. Only in Italy and France had Spalding been out of the British sphere of influence.

In 1908 Japan had been visited by the Reach All- Americans, but the tourists consisted of only one team, none of whom could even remotely be considered star players. They specialized in steamrolling local nines. The Reach All-Americans drubbed their Japanese opponents, sweeping all 17 games. The only positive aspect of the 1908 tour as far as the Japanese were concerned was that the humiliation fueled their desire to excel at the sport and to one day beat the Americans at their own game.

The tour by Comiskey and McGraw promised to bode far more goodwill for everyone. In the intervening years, players who had visited Japan on their own had smoothed over some of the hard feelings remaining from the Reach All-Americans. During the winter of 1910, Giants Arthur “Tillie” Shafer, a utility outfielder and second baseman, and Tommy Thompson, a pitcher, visited Japan and dispensed a great deal of good coaching on the finer points of the game to this very same Keio University. (Curiously, although Shafer was still on the Giants roster in 1913, he expressed no interest in going on the tour.)

The abilities of the American major leaguers, even after enduring the strength-sapping Pacific Ocean, were far above what everyone in Japan was familiar with. It was like knowing a few dance steps and then having Vernon and Irene Castle show up to give you a tutorial. They watched each play carefully, studying and learning. Of the various baseball skills, the art of pitching was the area where the Japanese lagged furthest behind the Americans. To the American sportswriters present, it seemed as if the Giants and White Sox had left their arms on the Empress, yet their pitchers still packed more heat than the locals had ever seen. The Japanese were also impressed with the prodigious home-run power of the tourists. Though the year 1913 is considered a part of the Deadball Era in the United States, it was a far livelier version of the game than the one in Japan.

After this game the tourists returned to the Grand Hotel for some hurried sightseeing and a feast that they could finally keep down. The banquet entertainment included geishas. Iva Thorpe was awed by their grace. Like all the banquets of the tour, this one included speeches and toasts and lasted until late in the evening.30

The next morning, Sunday, December 7, 1913, was the date for what was perhaps the most eagerly anticipated baseball game in Japan’s history. A team composed of White Sox and Giants was scheduled to challenge the Keio University team. For this event, 7,000 people crammed into Keio’s ball ground. This was to be the first game of a doubleheader. The White Sox and Giants were to play each other again in the afternoon, the last contest in Japan. The morning game marked the first time that the teams would challenge a local nine on their global sojourn. For the first time the two teams would play as one. The starting lineup of American big-leaguers that day consisted of Lee Magee, Larry Doyle, Fred Merkle, Hans Lobert, Mickey Doolan, and Ivey Wingo of the Giants, Tris Speaker, and Sam Crawford, of the White Sox. Death Valley Jim Scott of the White Sox pitched, and the Giants’ Mike Donlin replaced Crawford in right field after six innings. The early-morning hour of play meant that right field would be bathed in glare, leading Sam Crawford to remark, “And to think I came 7,000 miles to play the sun field.”31 Klem and Sheridan umpired the game, as they had all the others. Klem crouched behind the squatting catchers while Sheridan worked the bases. Klem’s booming voice and mannerisms were soon being imitated by the crowd.

Keio University’s baseball team was the best collegiate team and therefore the best team in all of Japan. There was no question that much Japanese pride rested on this contest. Keio batted first and played full bore. Shigeki Mori, Keio’s center fielder, tripled and a play later scored on Daisuke Miyake’s single. The crowd exploded with joy. By good fortune, Frank McGlynn and Victor Miller had the movie camera rolling. As Mori crossed the plate, Miller used the panoramic lens to get a wide shot of the 7,000 screaming fans in full ecstasy.

Moments later the Japanese were retired without further scoring. The Americans now got a chance to silence the crowd. Lee Magee, playing left field, matched Shigeki Mori by leading off with a triple. He scored immediately on Larry Doyle’s single. After the Americans were shut down in the second inning, the floodgates opened. The White Sox-Giants plated 16 runs, scoring in every inning. Keio scored only two more runs, for a final score ofl6-3.32

The game was not such a blowout as the score might indicate. The Americans found the Japanese to be very good ballplayers. Gus Axelson said of their playing that it was a “revelation to the major leaguers.”33 While their fielding, work on the bases, and ability to think on their feet were nearly as adept as the pros, the Japanese had one glaring weakness: pitching. Keio could not hit much American pitching, and their pitcher could not serve up much that the Americans could not hit.

The Japanese pitcher, Kazuma Sugase, also served as team captain. Nearly as tall as Jim Scott, he looked quite professorial in his owlish glasses. His arm, while mastering Japanese players, was no match for the White Sox and Giants. Every member of the team except Doolin and the still sea-woozy Weaver touched home at least once. Sugase did go the distance, however, and did not surrender any home runs. He walked fewer than did Scott, and he recorded three strikeouts. On the negative side, Magee tripled twice, Merkle was hit by a pitch, and Sugase had to endure three passed balls by his stone-gloved catcher, Tokuichi Takahama. The defensive highlight of the game for the Japanese had to be turning an exotic (third to first to third) double play that sent an awed Tris Speaker back to the bench.

Jim Scott started poorly but kept getting better as the game progressed. After he shook off the cobwebs of idleness and seasickness, his pitching completely mastered the university students. Scott surrendered single runs in the first, third, and fifth innings, then shut Keio down. In the ninth inning Scott was humming along so well that he struck out the side, ending the game with an awesome flourish. The game took a brisk 1 hour and 48 minutes from start to finish. What had started as a sporting event became a delightful encounter between cultures. Politeness ruled the day. The Americans were applauded by their hosts every time they made a good play. McGraw and the American pros were sincerely impressed with the Japanese’s abilities. Had a major-league-quality pitcher been on the mound for the Japanese, the results of the game could easily have been very different.

Great shouts of appreciation from the 7.000 fans erupted at the conclusion of the game, with lengthy ovations that poured over the Americans like a wall of sound. After the game there was just enough time for a quick lunch while the field was prepared for the afternoon contest. For the second time, the tourists played a morning-afternoon doubleheader. The first one had been on November 16 in Oakland and San Francisco, when everyone, even after a month of nonstop touring, had been in better shape.

The afternoon show, the last game played by the tourists in Japan, saw 6,000 fans retain their seats from the first game. The Japanese continued to revel in the tourists’ skillful ballplaying. The Giants and White Sox used their regular lineups against each other, with most of those who had played in the morning back in action in the afternoon. The White Sox swept the “series” in Japan, winning the second game, 12-9.

This game ended with one of the most thrilling plays of the entire tour. Tris Speaker threw Mike Donlin out at the plate from the deepest part of center with an absolutely perfect throw to Ivey Wingo. An amazed John McGraw called it one of the greatest plays he had ever seen. The awed Japanese fans cheered the play in a riotous cacophony of sound. No dramatist could have come up with a more appropriate ending to the game or the series in Japan.34

The women of the party were not in attendance for either of the day’s games. Rather than sit through more baseball, all of the wives were on the Empress, sailing ahead of their mates to Osaka. The men joined them many hours later; after the second game the athletes caught the first train out of Tokyo for Osaka.

The Japanese press ran out of superlatives and hyperbole in describing what they had witnessed. The Yokohama Gazette stated: “The games played have been a revelation to those who had not witnessed anything of the sort before.”35 The Japan Advertiser of Tokyo said: “The teams seem to move like clockwork. Each signal is exactly followed and the umpire’s decision is obeyed silently. It is this system of arbitration that the ball player of this country must note and develop so that further friction in international base ball games may be averted. The speed and alacrity of the base stealing, too, was a revelation to the Japanese.”36 The Tokyo Times reported:

Like a cyclone the big men of America came and went, creating a whirlwind of sensation. What did they do? Well ask the fans; they know it. And also ask those people living down in the Mita Road, and they will give complete statistics of windows smashed, houses damaged, and dogs in the street hit by flying balls. They worked more wonders and showed more true ball playing than the Japanese fans could see. The cyclonic visit of the American stars has left its memory in the sporting history of Japan—besides those mementos on some houses in the neighborhood of the Keio grounds. And fortunate was the Keio team, which was able to get practical suggestions and advice from such base ball brains as John McGraw and Jim Callahan.37

After the game some of the party returned to the Grand Hotel. Most of the players, however, checked into the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo, which was much closer to the ballpark. Everyone tried to squeeze in some sightseeing and banqueting before reporting to the train station for a journey by rail to Osaka.38

Upon boarding the 7:00 P.M. train at the station for the nearly 13-hour train ride, the players had one more culture shock. The size of the train’s berths was a most depressing discovery. Built for the smaller stature of the Japanese, the berths measured only five feet eight inches long and two feet wide. Ivey Wingo in particular was especially perturbed. Wingo caught both ends of the doubleheader and wanted nothing more than to lie down and rest his aching bones. That was, however, impossible for the 5-foot-10-inch, 160-pound catcher to do comfortably. Wingo whined that he would probably be crippled for life if he got into his berth. Sleep is a powerful force, though, and before long all of the men, including 6-foot Tris Speaker, were crammed into their berths speeding through the night-shrouded Japanese landscape, the only sound, snores mixed with the steady hum of steel upon steel.39

The ballplayers’ train pulled into the Osaka terminal at 7:30 A.M. on December 9. Awaiting the train was the city’s large, loud, and enthusiastic welcoming committee. Cheers went up, along with calls for McGraw, Callahan, and Doyle. All of the players emerged stiff-limbed and bleary- eyed to a thunderous ovation. McGraw and Callahan were presented with two elaborate floral wreaths, each carried by young Japanese girls. Elsewhere, men hoisted banners with welcoming messages in English high above the milling crowd.

The committee and the citizens of Osaka were greatly disappointed that the game scheduled for their city had been canceled. The chairman of the welcoming committee, an English-speaking editor of the Osaka Daily News, while understanding the reason for the cancellation, could not hide his sadness. Callahan and McGraw made brief speeches. Then it was on to Kobe to the thunderous shouts and cheers of the Japanese.

The players arrived in Kobe at 9:00 A.M. The wives had already spent a most enjoyable day in Kobe shopping, sightseeing, and socializing. For the next three hours the men went on a buying spree. Kimonos, silk, summer clothing, souve- nirs,jewelry, gifts for spouses and girlfriends—in short, everything that could be bought. At 12:30 in the afternoon everyone returned to the Empress. At 2:00 P.M. the ship sailed out of the harbor, making for Nagasaki at full speed. Nagasaki was like no other city in Japan. The fastest coaling station on the planet, the city moved at a quicker pace than the rest of the country. Unlike elsewhere in Japan, where women played a subservient role, in Nagasaki they were an essential part of the coaling operations, the city’s prime source of revenue.

Women dressed in white performed most of the work. As soon as a ship dropped anchor in the harbor, coal barges surrounded it, and coaling operations commenced. Men threw ropes woven out of rice plants over the side of the vessel. These were then lashed to the deck, a process that took only a matter of seconds. Once the ladders were in place, an army of women, each standing above the other on the rungs of the rice ladder, passed a 28-pound basket of coal up from the barge to the ship’s bunkers. Once emptied, the basket was tossed back to the coaling barge to be refilled for another journey up the ladder. There were about 25 crews working on each side of the Empress from noon until 10:30 P.M. The women toiled like ants moving earth. When they were finished, 1,500 tons of coal had been transported into the ship’s cavernous bunkers. For their labors, the women received the equivalent of 20 US cents.40

Witnessing this toil was too much for some tourists. As Frank McGlynn put it, “[T]he liberal hearted members of the world touring party threw coins to the patient laborers, and no doubt a great majority of them were happier at their day’s pay than on many a similar occasion.”41

Unlike Kobe and Osaka, no game had been planned for Nagasaki; December 9 had been a scheduled treat for the players, an open date. To the players’ delight, Nagasaki offered more diversions and attractions than did even Tokyo. For the first time since they had sailed out of Seattle, the players got a chance to relax and enjoy themselves.

The Thorpes did some Christmas shopping, toured around town in rickshas, then, like most visitors to Nagasaki, ascended the thousands of steps to the top of the temple. Here as well they got to see how the ordinary Japanese citizen lived. Iva took note of the local custom of attaching a piece of rice paper to the door to ward off evil spirits. Away from the more urban and industrial centers of Kobe and Tokyo, the tourists encountered a Japan more ancient, mysterious, and delightful than they imagined.42

But like just about everywhere the tourists appeared, trouble followed. Fred Merkle, Mike Donlin, Germany Schaefer, and a few other of the tour’s bachelors went out for drinks with the officers from an American liner whom they had befriended. In some dive near the waterfront, the sailors and the ballplayers stumbled across a pool table. Like delighted children encountering a favorite toy or delinquents finding their favorite vice, the group proceeded to play round after round.

Billiard balls and alcohol shots chased each other for hours. Finally, close to 10:30 P.M., the players realized that the launch for the Empress would soon be leaving and that if they didn’t catch it, there was a chance all of them might get left in Nagasaki. If nothing else, they had to get back on time to avoid a tongue-lashing from McGraw. One of the hard-partying athletes chose to take one last shot for the road and, in his drunken state, sent the cue ball careening off the table and onto the floor before it disappeared under a couch. Too drunk to bend over, the players left the ball where it was and beat a hasty return to the Empress43

The players’ actions, however, did not escape the notice of the harbor police. Unable to find his valuable cue ball, which, after all, was made out of solid ivory, the owner of the bar reported it stolen and named the American ballplayers as the prime suspects. To the athletes’ chagrin and the steamship line’s supreme displeasure, Nagasaki’s harbor police boarded the Empress, demanding the missing cue ball and an explanation from the plastered Americans.

Germany Schaefer approached the police, turned on the charm, and confessed to his misadventure. While Schaefer was trying to charm his way out of arrest, word came to the police that the location of the “missing” cue ball had been discovered, and the Empress was now free to sail.

Immediately inflated by the American press, the cue-ball story became fodder for US tabloids and scandal sheets. Axelson and Farrell, the writers on the tour, protected the athletes they covered; they did their best to sweep the story under the rug. After all, it just would not do to have reports of drunken ballplayers in the newspaper.

Under the cold light of a waning moon, hours past the scheduled departure time of midnight, the Empress slipped out of Nagasaki for Shanghai.

STEPHEN D. BOREN, MD, attended the University of Illinois for two years and then received his MD degree four years later from the University of Illinois College of Medicine. After an internship at the University of Illinois Hospital, he was drafted into the US Army and was stationed in the north part of south Korea where the real M*A*S*H had been. He subsequently did his emergency medicine residency at Milwaukee County Hospital. He later earned his MBA from Northwestern University. He has published articles in numerous SABR publications. He believes that he is the only person to be published in the Wall Street Journal, the New England Journal of Medicine, and Baseball Digest all in the same year. His mother wrote her Master of Arts dissertation at the University of Chicago in 1936 entitled “Athletics as a Factor In Japanese International and Domestic Relations.” He has been board-certified in emergency medicine five times. He and his wife, Louise, as well as his well- known golden retriever Charlie, now reside in Aiken, South Carolina.

JAMES E. ELFERS is the author of the Larry Ritter Award-winning book The Tour to End All Tours: The Story of Major League Baseball’s 1913-1914 World Tour (University of Nebraska Press, 2003), a chapter of which was excerpted for this volume. This book was also a Seymour Award nominee and runner-up for the Casey Award for best baseball book of the year. Elfers is retired from the University of Delaware, where he spent 35 years at the Morris Library, mostly as a cataloger. A lifelong Phillies fan, he has seen lots of bad baseball with occasional flashes of brilliance. He currently resides in Pennsylvania’s Lehigh Valley with Patti, the love of his life and a fellow writer. A Brit, she reminds him regularly that baseball is basically rounders. Elfers keeps his library skills up to snuff by working part time in his local community library. He can be reached at jeelfers@netscape.net.

NOTES

1 “A Joint Tour,” Sporting Life, February 1, 1913: 1.

2 Spalding’s Base Ball Guide and Official League Book for 1889 (Chicago and New York: A.G. Spalding & Bros, 1889), 83-99.

3 Harvey T. Woodruff, “The Tour of the World,” Sporting Life, October 11, 1913: 5.

4 “Latest News by Telegraph Briefly Told,” Sporting Life, May 17, 1913: 7.

5 “Wilson Will Help,” Sporting Life, June 21, 1913: 6.

6 “Fine Plans for the World Tour,” Sporting Life, June 28, 1913: 2.

7 Joseph Vila, “World Tour Cost Deters,” Sporting Life, July 19, 1913: 8.

8 “The World Tour Assured,” Sporting Life, August 2, 1913: 2; Joseph Vila, “World Tour Cost Deters,” Sporting Life, July 19, 1913: 8.

9 “Cost of World Tour,” Sporting Life, September 27, 1913: 1.

10 Woodruff.

11 “Start of World Tour,” Sporting Life, October 25, 1913: 1; James E. Elfers, The Tour to End All Tours (Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2003), 94.

12 “The Tour of the World,” Sporting Life, November 22, 1913: 4.

13 “The Tour of the World,” Sporting Life, November 29, 1913: 5, 9.

14 “The Tour of the World,” Sporting Life, November 29, 1913: 9; Anon., World Tour 1913-1914 (Chicago: S. Blake Willsden, 1914).

15 Elfers, 98-107.

16 Adapted from The Tour to End All Tours: The Story of Major League Baseball’s 1913-1914 World Tour by James E. Elfers by permission of the University of Nebraska Press. Copyright 2003 by the University of Nebraska Press.

17 Gus Axelson, “Sox Take First in Orient Play: Romp at Tokio,” Chicago Sunday Record Herald, December 7, 1913: Sports section, 1.

18 Jiji Shimpo, December 7, 1913.

19 Jiji Shimpo, December 7, 1913.

20 Jiji Shimpo, December 7, 1913.

21 Jiji Shimpo, December 7, 1913.

22 Joe Farrell, “World Tourists’ Rough Voyage Across Pacific Ocean,” The Sporting News, January 1, 1914: 5.

23 Frank McGlynn, “Striking Scenes from Around the World: Part I,” Base Ball Magazine September 1914: 67.

24 Farrell.

25 Farrell.

26 Iva Thorpe, Personal Diary. Private Collection.

27 Farrell.

28 Farrell; Frank McGlynn, “Striking Scenes from Around the World: Part II,” Base Ball Magazine, October 1914: 69.

29 Axelson.

30 Thorpe; Farrell.

31 Gus W. Axelson, “Japanese Quick to Adopt Big League Ways,” Chicago Record-Herald, December 28, 1913.

32 McGlynn, “Striking Scenes from Around the World Part I”: 68.

33 Axelson, “Japanese Quick to Adopt Big League Ways.”

34 Gus W. Axelson, Commy: The Life Story of Charles A. Comiskey (Chicago: Riley & Lea, 1919), 251.

35 “How Press of Japan Viewed Invasion of World Tourists,” The Sporting News, January 8, 1914: 3.

36 “How Press of Japan Viewed Invasion of World Tourists.”

37 “How Press of Japan Viewed Invasion of World Tourists.”

38 McGlynn, “Striking Scenes from Around the World Part II”: 69.

39 McGlynn, “Striking Scenes from Around the World Part II”: 70.

40 McGlynn, “Striking Scenes from Around the World Part II”: 71.

41 McGlynn, “Striking Scenes from Around the World Part I”: 71.

42 Thorpe.

43 McGlynn, “Striking Scenes from Around the World Part II”: 71-72.